Detail of Mary MacDougall, Window frags, 2024, glazed ceramic, dimensions variable. Courtesy ReadingRoom, Naarm / Melbourne. Photo: André Piguet.

Under Five Windows

Francis Plagne

Curatorial talk is bad for your health. For anyone who has breathed in a little too much of the self-important air that thickens the atmosphere inside the contemporary art bubble, it makes for a restorative change to visit Under Five Windows at ReadingRoom, a group exhibition that does not appear to have been conceived principally as an impressive line on the CV of yet another emerging curator. It brings together five artists, all born between the early 80s and the early 90s: two Australians (Jana Hawkins-Andersen and Mary MacDougall), a North American (Nikholis Planck), a Frenchman (Paul Bonnet), and a Pole (Mateusz Woś). At the centre of the quincunx is MacDougall, who has selected the other four, none of whom, to my knowledge, know each other. In the absence of an overarching theme or organising principle, the exhibition suggests that these five artists, distinctive though they may be in terms of processes, materials and reference points, share a sensibility of some kind.

Nikholis Planck, Untitled (staircase w/ sandbag), 2022, water soluble oil and coloured pencil on conjoined wax paper, 60 × 66 cm. Courtesy ReadingRoom, Naarm / Melbourne. Photo: André Piguet.

One key element of this sensibility is an investment both in the materiality of artmaking and in figuration. Most striking in this regard are the unorthodox supports used by some of the painters. One of the highlights of the exhibition is Planck’s Untitled (staircase w/ sandbag) (2022), executed in oil and pencil on wax paper, the translucency of which is visible around its scrappy edges. The wax paper creates a shiny, insubstantial surface at odds with the moody depiction of a stone staircase in loosely applied strokes of purplish paint. In Planck’s work, the way materials are handled strains the recognition on which depiction depends. Looking at Untitled (Study for Wings Lower Right Flank) (2019–21), I know I am looking at something, not merely abstract marks, but I’ve no clear idea what it is. In MacDougall’s work, this dynamic is in a sense reversed. Rather than snatches of depiction deformed through the handling of materials, the process of applying marks to the surface reveals imagery. In Spider Blankets (2024), painted in glaze on fifteen wonky ceramic tiles made by the artist, splattered asterisks on skewed chequerboard patterns have cohered almost by accident into the titular arachnoids.

Mary MacDougall, Spider blankets, 2024, glazed ceramic with chalk, 68.5 × 45 cm. Courtesy ReadingRoom, Naarm / Melbourne. Photo: André Piguet.

Jana Hawkins-Andersen, Gate Fragment II, 2023, glazed ceramic, 21 × 19 cm. Courtesy ReadingRoom, Naarm / Melbourne. Photo: André Piguet.

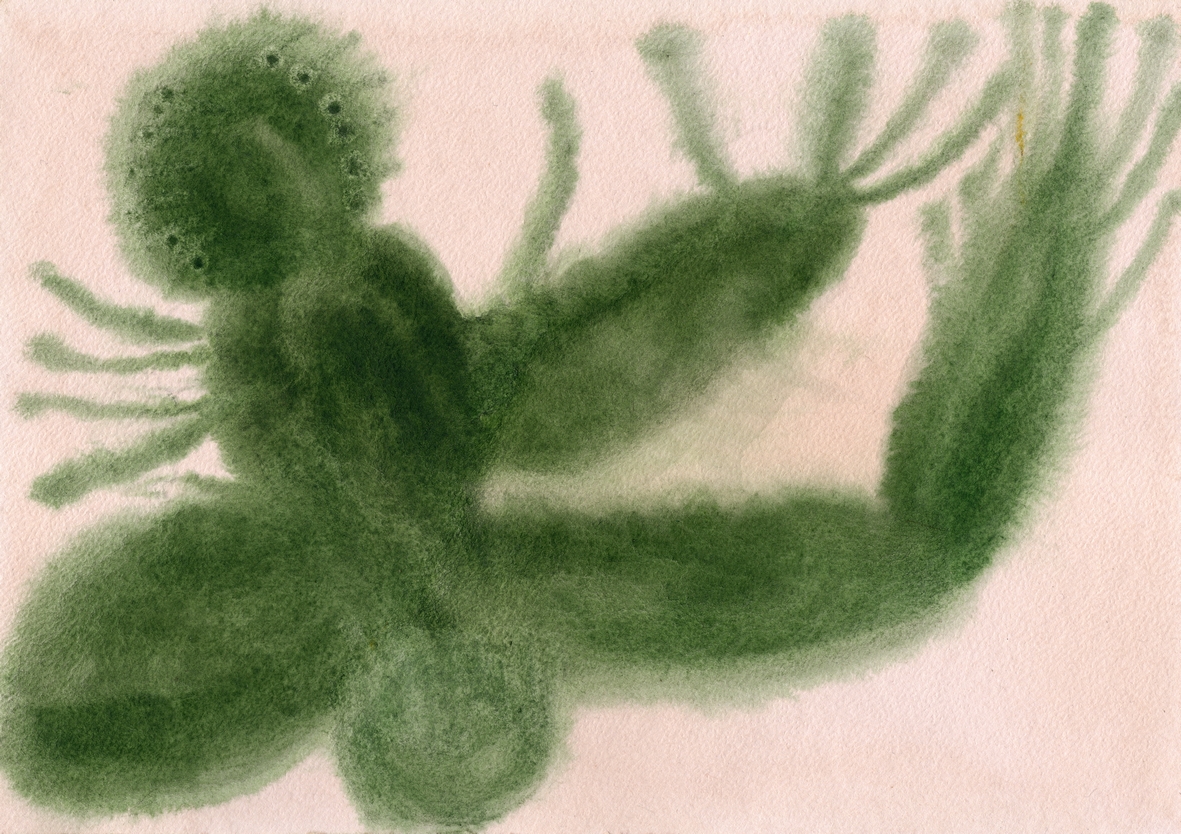

Much of the imagery here is natural: MacDougall’s spiders; the pre-historic landscape of Bonnet’s Late Archean (2024); even the Gate Fragments (2023) of Hawkins-Andersen, which in their pointedly handmade approximation of traditional wrought iron decoration call up the vegetal sources of these forms as much as the blacksmith’s forge. Ants, butterflies, and fossils fill Woś’s A4 watercolours, bleeding into amorphism like Rorschach prints, spreading to the framing edges like the children’s drawings Dubuffet copied. They are selections from an extensive series called Columbarium (2023), the name given to the structure in which funerary urns are stored. It is an appropriately gothic title for the imagery, but also a clever one. The word, the dictionary tells me, derives from columba (dove) and can also be used for a dovecot or pigeon-house: like these structures of identical niches storing birds or ashes, each in some way unique, each uniform A4 page of Wos’s series houses a different creepy specimen of the imagination.

Mateusz Woś, Untitled (from the series Columbarium), 2023, watercolour on paper, 21 × 30 cm. Courtesy ReadingRoom, Naarm / Melbourne. Photo: André Piguet

MacDougall’s brief essay is accompanied by a Bashō haiku: “Mad with poetry, / I stride like Chikusai / into the wind.” This is the translation by Lucien Stryk; in the slower version by Nobuyuki Yuasa, it goes: ‘With a bit of madness in me / Which is poetry, / I plod along like Chikusai / Among the wails of the wind.” It’s a romantic image of creativity, obviously, but it takes on a slightly different tone when we learn that Chikusai is the hero of early seventeenth-century popular narratives concerning the comic exploits of a fraudulent doctor and his patients. Bashō wrote the haiku, he tells us, “In Nagoya, where crazy Chikusai is said to have practised quackery and poetry.” The quote suggests that art—at least the kind practised by these five artists—is a kind of folly, something whose meaning and usefulness cannot be measured by standards that obtain in other aspects of life. It is something done for the most part alone, behind the windows of these five separate studios (or, perhaps more likely, home studios).

Paul Bonnet, Heaven is sad I–V, 2023, acrylic on paper, 42 × 29 cm. Courtesy ReadingRoom, Naarm / Melbourne. Photo: André Piguet.

Installation view of Under Five Windows, ReadingRoom. Courtesy ReadingRoom, Naarm / Melbourne. Photo: André Piguet

The sense of exploratory studio practice is strong in the exhibition. (One almost wishes for some Alexander Liberman-style photographs of where the artists work, their tools and materials.) The show concerns art as process, but not in the way Richard Serra splashing lead does. Rather, it speaks of sitting down at the worktable each day, trying again to make something satisfying. This is reinforced by the charming use made of the gallery’s back room, where we find smaller works displayed on walls, and laid flat in drawers, like supplementary material in a museum survey. There is a possibility this could appear pretentious or self-aggrandising (it’s usually studies by the masters we see presented this way), but the effect is quite the opposite, poking holes in any slickness or grand statement made by the main exhibition space. Paul Bonnet’s sizable oil Late Archean gains from the company of the five smaller studies of bedrooms, views out of windows, landscapes and snatches of street show in the back room. Executed in broad strokes in very wet watercolour that has warped the paper support, their sketched forms and subtly odd colour choices make the more strikingly garish colour palette of the large painting seem somehow more earnest, less deliberately pop-shock-Fluro. Encountering Hawkin-Andersen’s fragments of ceramic gates inside a drawer makes them more enigmatic, less obviously tied to contemporary art norms, than they appear in their elegant spatial display in the front gallery.

MacDougall is a friend of mine and we share quite a few musical, artistic, and literary enthusiasms. One of them is for the deep vein of crystalline improvisatory non-sense mined by octogenarian poet Clark Coolidge, friend of and collaborator with Philip Guston. I know that MacDougall is particularly fond of a dialogue between Coolidge and Guston recorded in 1972 at the painter’s house in Woodstock. One of the themes of this conversation is the importance of the artist’s own discontent with their work as a motor of creativity: “You could make a principle of discontent,” Guston says. This resonates with the development of MacDougall’s work over recent years. Where her work of a decade ago shared something with the contemporary mode of dandyish abstraction that aspires to the elegance of the slapdash, her surfaces have in recent years become denser, more obviously worked and layered. In the paintings in glaze on ceramic tiles exhibited here, form is muddled by reworking, clarity of line blurred by repeated firings. Geometry is interrupted by inky splatter; blocks of colour cut windows into scribbled mass. MacDougall creates an ambiguous sense of depth connected to both textual palimpsests and the impossible, shimmering pseudo-space of cubism.

The great English novelist Henry Green—whose books read something like a wondrously bizarre mixture of Samuel Beckett and P. G. Wodehouse—in later life generally read eight novels each week. According to his son, he would rarely discuss his reading. If pressed for his opinion of a particular book, he would reply only “good!” or “pitiably bad!” Beneath this kind of inarticulate response lies a complex of intellectual, imaginative, and emotional impressions, difficult to formulate; liking and disliking works of art is one of the ways in which these impressions cohere and find formulation. (Maybe “influence” is another?) In some contemporary art, like and dislike become close to irrelevant: we might understand, get the joke, be prompted to conversation and so on, but the aesthetic response of like or dislike can seem beside the point. Visiting Under Five Windows might move you to say “good!” or a more insightful version of the same; you might even (though it seems unlikely) say “pitiably bad!” Either way, it is refreshing to share the company of these artists, among whom it seems that precisely this kind of aesthetic experience is what matters.

Francis Plagne is a musician and writer who teaches at the University of Melbourne.

This review was made possible thanks to the generous support of Meridian Sculpture.