Frida Kahlo: In her own image, installation view. Photograph by Leon Schoots.

Frida Kahlo: In Her Own Image

Scott Robinson

She is in the process of remaking herself in another medium than life and is becoming resplendent. The flesh made sign.

—Angela Carter

Since the era of struggle over the image of Frida Kahlo has passed—with her recovery from under the groaning artistic stature of her husband, Diego Rivera, decisively achieved—her cultural status seems to have settled into a resigned reverence. In Frida Kahlo: In Her Own Image, we are exhorted to venerate the idol. The labels of the 1990s, “Fridamania, Fridolatry, Fridaphilia,” are no longer needed to excuse the canonisation of “Frida” as an icon of the self-assertive, self-representing woman. The ubiquity of self-portraiture has silenced any lingering questions about the narcissism of obsessive self-representation, and the generous expansion of the gallery to include pretty much any material even tangentially associated with art or an artist has paved the way for an exhibition composed almost entirely of documentary images, clothing, and ephemera. This exhibition takes for granted—even elides—Kahlo’s art works as the defining feature of her reputation, and focuses on her self-presentation in photographic images and through sartorial decisions.

A touring exhibition, initially centred on her clothing at the Museo Frida Kahlo in 2012, called Las Apariencias Engañan (sponsored by Vogue Mexico), Frida Kahlo had greatly expanded iterations at the V&A (2018), under the title Making Her Self Up, and the Brooklyn Museum (2019), with the title Appearances Can Be Deceiving. These titles suggest different interpretations of similar core material, and also different emphases in its presentation. In Bendigo, the emphasis is on the image, both in terms of the visual representation of Frida Kahlo, and in terms of the prevailing conception of her.

What is remarkable is that the exhibition is almost entirely composed of images not taken by Kahlo herself. We might do well to moderate our expectations in visiting by distinguishing between images of someone, and their own image(s). If we are not to catch what Jorge Alberto Lozoya calls the “virus of fetishism” so easily transmitted in exhibitions of Kahlo, we might also want to distinguish between the artist and her image. Kahlo’s magnetism for photographers should not entail her conflation with an image, and the insistence on her agency in the composition of these images can obscure the reality of their production by someone else.

Emmy Lou Packard, Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera at home in Coyoacan, Mexico, 1941. Emmy Lou Packard Papers, 1900-1990. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

Among the luminaries, commercial photographers, and members of her and Rivera’s artistic circle who aimed their lens at Kahlo are Edward Weston, Imogen Cunningham, Gisèle Freund, Lucienne Bloch, Martin Munkácsi, Toni Frissell, Bernard Silberstein, Nickolas Muray, Emmy Lou Packard, Sylvia Salmi, Florence Arquin, and Lola and Manuel Álvarez Bravo. Of course, this grouping must be dissected into categories in order to appreciate the difference between family portraits, tokens of friendship, intimacy or collaboration, fashion photographs, studio documentation, and staged portraits. Should we really treat all these as constructing “her own image”?

One story promulgated by the exhibition is that her taste for posing was ignited by her father, Guillermo Kahlo. Yet one would not like to say that images made by her lover Nickolas Muray bear this taste in anything but the crudest Freudian terms. Nor would one like to say that images produced by an intimate share their specific intensity with those taken by commercial photographers. Can we accept that images of a person can be impersonal, and, indeed, that the most performative self-presentation is hardly what we should use to diagnose the depths of someone’s character?

Commercial photographers like Toni Frissell and Martin Munkácsi capture some of the drama of Kahlo’s presence but impersonally, while Florence Arquin was on assignment from the US State Department. Munkácsi’s close double portrait of Rivera and Kahlo stands apart from his oeuvre for its stillness. The intensity of Rivera’s stare is unnerving. Kahlo described Rivera’s “wide, dark, and intelligent bulging eyes… barely held in place by his swollen eyelids. They protrude like the eyes of a frog, each separated from the other in the most extraordinary way.”

Some photographers were themselves minor artists, like Sylvia Salmi and Emmy Lou Packard, brought into the orbit of Kahlo and Rivera. In Packard’s 1941 portrait of Rivera, for whom she worked as a studio assistant, he squats like a stone idol. Packard’s photographs are more relaxed, some candid, others simply moments of ordinary life turned into traces of artistic production. Her portraits are unburdened by idolatry. Kahlo clearly trusted Packard, sending her ferocious letters about Rivera’s second wife Guadalupe Marín (“something that makes me want to vomit. She is absolutely a son of a bitch”) in which she expressed a desire to “never come back to any thing which means publicity or lousy gossip.”

Nickolas Muray, Frida Kahlo in blue satin blouse, 1939 © Nickolas Muray Photo Archives.

Manuel Álvarez Bravo was more directly connected to Rivera and Kahlo’s sphere of revolutionary left-wing nationalism, but his photographs demonstrate a delicate aesthetic sensibility with an almost classical orientation. Frida Kahlo (con globo de cristal) (c. 1939) is contemplative and still, pulling attention away from the sitter with a reflective metal sphere. The opposite strategy is adopted by Nickolas Muray, whose portraits emanate with the intensity of the reciprocated lover’s gaze. Yet some of the same classical stillness remains in colour portraits of Kahlo in the late 1930s and early 1940s. Reprinted for the exhibition, these are some of the best-known portraits of Kahlo, abstracting her figure entirely from its milieu. Highly stylised, they suggest a playful parade of costumes, and involve Kahlo’s most direct engagement with the eye of the camera.

Amid the public depictions, her father continued to photograph Kahlo. The exhibition includes a 1932 picture taken after her miscarriage and the death of her mother. Kahlo’s face is grim, but hardly grief-stricken. The photograph, without the context, would not betray her recent losses, no more than could be interpreted from other photographs in the exhibition. Perhaps it is Kahlo’s bold and elastic features that enable various biographical details to implant themselves so firmly on our image of her. And yet, as photographer and theorist Gisèle Freund observes in Photography and Society (1980), the context of production and distribution significantly shape our reception of images, especially what we see “as real.” For all the interest in the (usually biographical) context of the production of images of Kahlo, their distribution and likely audience are unmentioned.

Guillermo Kahlo, Frida Kahlo, 1932 © Frida Kahlo Museum

Photographs are used in the exhibition not in order to frame her work as an artist, but in order to frame her life and contextualise the clothing and other paraphernalia that is on display. Photographs of her painting are used to highlight some aspect of her life—often a relationship, with Rivera, with Dr Farill, with Muray, or with her own injuries or bodily condition—rather than to shed light on her work.

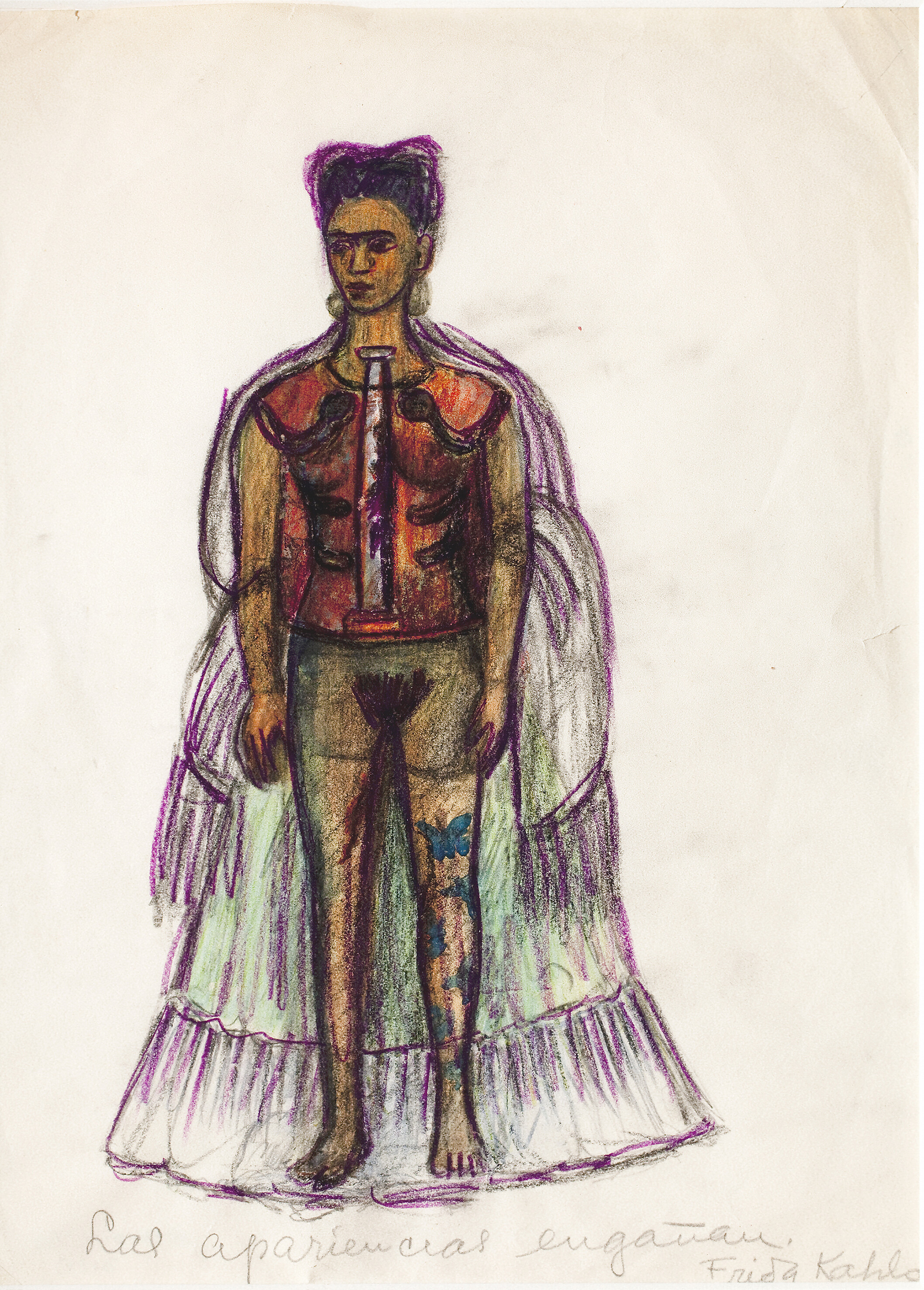

Her clothing takes centre stage, displayed prominently in large vitrines. These are the trophies of an archival release from the previously closed La Casa Azul in Mexico City in 2004. Among this trove of new material was a drawing by Kahlo called Appearances Can Be Deceiving (1934), an X-ray depiction of her own dressed body that strips back clothes and even flesh to reveal a metallic spine. Critics and commentators on Kahlo are divided over whether the construction of her self-image constitutes a subjection to (or worse, embrace of) fetishism, or a form of agency. Kahlo seems to have become a cipher for what Angela McRobbie calls “various post-feminist disorders” over the representation of women’s bodies and the status of appearances.

The approach to whatever lingering and increasingly dated fears there are about the objectification of women is a kind of doublethink in which every kind of objectification is in fact an expression of agency and authentic articulation of the self. Kahlo’s use of Tehuana costume and other indigenous garments and styles (liberally mixed with European and Asian clothes) is frequently linked to a recovery of her mother’s ancestry as well as the broader indigenista movement. Predictably, this has drawn recent accusations of appropriation such as those from Purépucha photographer and writer Joanna Garcı́a Cherán. The famous Kahlo “look” is in fact lifted.

Frida Kahlo, Appearances can be deceiving, 1934, charcoal and pencil on paper. Collection Museo Frida Kahlo. © Diego Riviera and Frida Kahlo Archives, Banco de México, Fiduciary of the Trust of the Diego Riviera and Frida Kahlo Museums.

The exhibition, likewise, lifts the clothing from the body and installs it on grey mannequins whose features are eerily smoothed-out renditions of Kahlo’s own. The aim seems to have been not to mimic too closely Kahlo’s features and yet suggest them with a crown braid and high cheekbones. The overall effect is one of bland feminisation of a famously masculine visage, with blank, empty expressions atop forms which give body to the dead artist’s clothes. Kahlo anticipated the cheap imitations of her style, suggesting mockingly that “some of the gringa women are imitating me and trying to dress ‘a la Mexicana,’ but the poor souls only look like cabbages and to tell you the naked truth they look absolutely impossible.” As Oriana Baddeley suggests, whatever Kahlo’s intentions in the adoption of Mexican clothing, the styles have “lost (their) function as a symbol of nationhood, becoming instead an icon of female suffering.”

Even her debilitating injuries and illnesses are presented in the exhibition as opportunities for self-expression. This is most notable in two rooms: one dedicated to displaying her casts, orthopaedic corsets, crutches, and shoes; and the other filled with the remnants of her medicines, cosmetics, and clinical history. There is something obscene in this display, not in the sense of a transgressive exposure of what cannot be tolerated (the abject), but rather in the sense defined by Hal Foster of indecently probing the screen/scene of representation in order to get to “the real.” By embracing the fetishism of Kahlo wholeheartedly, this obscene display may be reintegrated into image-space and so become the object of the perverted desire described by Georges Bataille’s anti-Bretonian quip, “I defy any amateur of painting to love a picture as much as the fetishist loves a shoe.”

The exhibition takes the obscene desire to discover the real person in their abjection and re-routes it into the fetishist’s love of the image-object. We cannot in fact smell the perfumes, nor taste the medication, other than as fantasies rendered by our devotion to Kahlo’s image. The best we seem to be able to do is identify with and adopt the most aestheticised aspects of her life. Visitors wander the gallery walls dressed like their icon, as if to draw her sanctifying gaze. Instead of entering the body’s sites of hunger and suffering, the objects on display draw them to the surface and treat them as images. Empty casts and corsets, decorated with the communist hammer and sickle, allow us not to imagine the torture of the surgeries that produced them. We can don the garb of martyrdom without undergoing it.

Orthopaedic corsets, installation view. Photograph by Leon Schoots.

Unlike the self-representation in her paintings, the display of objects divides the artist into inert portions. Walter Benjamin remarked that the “parcelling out of feminine beauty into its noteworthy constituents resembles a dissection.” The dissection enables an uncanny resurrection of Kahlo in idealised form, as if in death she has conquered pain. The display of medications, clothes, and other accoutrements of a constructed image only intensifies the common critical argument that Kahlo was complicit with the construction of a cult of herself. The cultic process of uncovering parts of her life, no matter how mundane or properly private they may be, both fuels the desire for proximity and also perhaps unwittingly exhausts the image, which becomes instead a series of franchised components, from cookery to clothing. Each iteration enables us to identify more and more closely with the image of the woman, an image that even during her life was turned towards death and the corpse.

What is missing in the staged liveliness of the photographs is the extent to which, in her paintings, life is almost always leaking out of the self-portrait. Vital organs are exposed or even separated from her body as in her Self-portrait with the Portrait of Doctor Farill (1951). This self-portrait is represented in Gisèle Freund’s 1951 photograph. The striking degree of synchrony between Dr Farill’s stare in the photograph and painting displayed within it is one of the few silent indications in the exhibition that Kahlo worked extensively from photographs. In both depictions, Farill’s gaze is drawn away from both Kahlo and the photographer in a way that resembles the strange inattention to the cadaver in Rembrandt’s The Anatomy Lesson of Dr Nicolaes Tulp (1550). No one, least of all the administering doctor, can bear the sight of death.

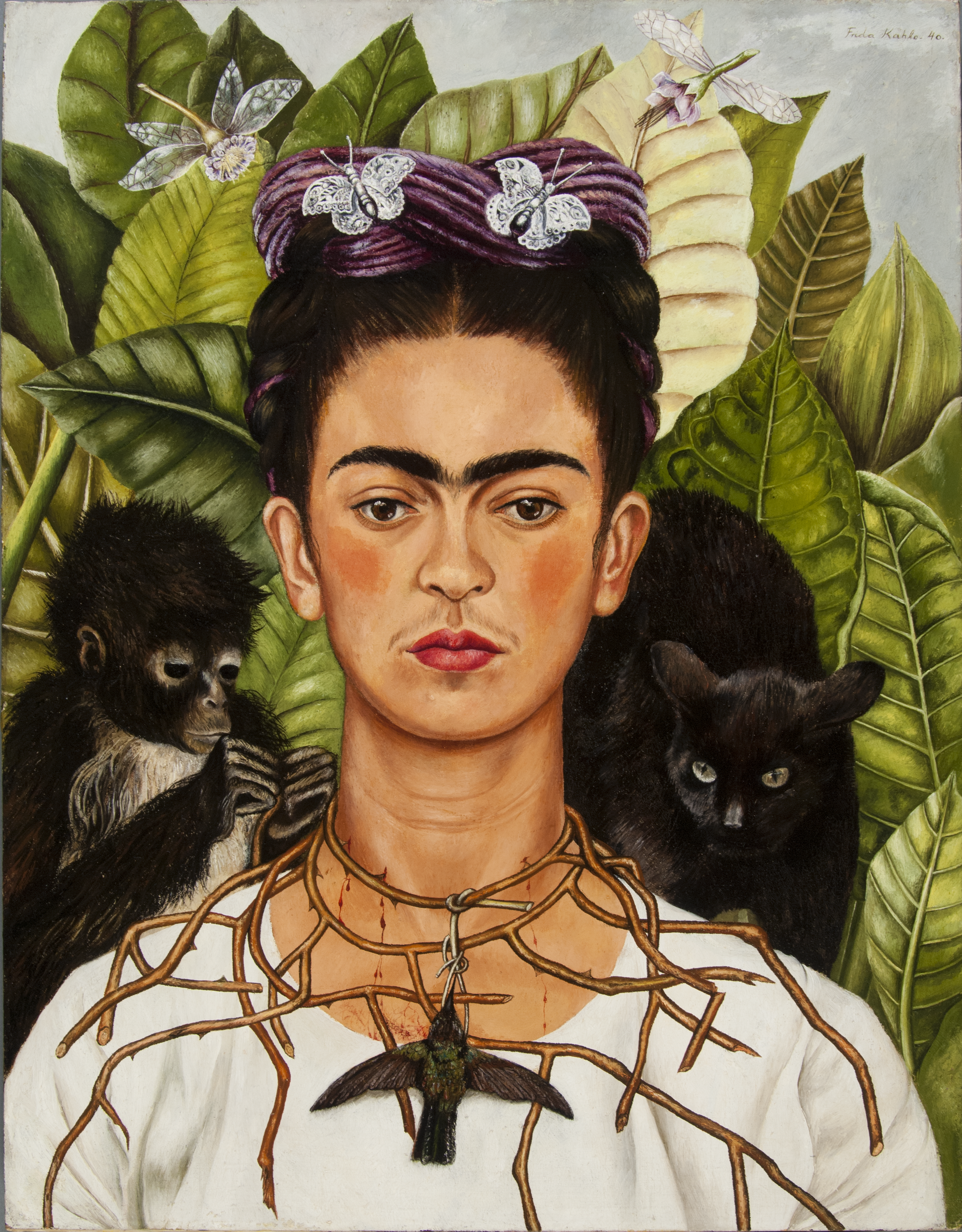

Frida Kahlo, Self-portrait with thorn necklace and hummingbird 1940. Nickolas Muray Collection of Mexican Art, Harry Ransom Center, University of Texas at Austin © Banco de México, Fiduciary of the Trust of the Diego Riviera and Frida Kahlo Museums.

One of the few paintings presented for In her Own Image is Kahlo’s Self Portrait with Thorn Necklace and Hummingbird (1940), whose iconography unmistakably recalls Christ’s crown of thorns, Kahlo’s monkey, and a black cat modelled directly from a photograph by Munkácsi. In a diary page from 1953, shortly before her death, she represents two amputated feet, crossed in the manner of Christ on the Cross, sprouting thorns amid a sea of red ink. She wrote, “I hope the exit is joyful, and I hope never to return,” giving her Acéphale-esque self-portrait wings: in the place of a head sits a dove. Her contribution of martyrology is sealed by another diary page, depicting herself in outline as Saint Sebastian subject to arrows while an inky face floats off her shoulder as if she has already departed her own body. Or perhaps “Frida” is simply never where we expect her to be, always doubled, or trebled as in a 1931 pencil drawing or chaotic 1926 drawing of her accident presented in the exhibition.

Three Kahlos also inhabit Muray’s 1939 photograph of Kahlo posing with her brush and palette in front of The Two Fridas, in which she appears to be giving herself company against a backdrop of gloomy clouds reminiscent of El Greco’s Christ on the Cross Adored by Two Donors (c. 1590). The painting’s left “Frida” has an exposed, leaking heart; both wear blank expressions. The setting is reproduced in a large, perplexing diorama of two seated mannequins wearing Kahlo’s clothing (it appears), holding hands in the manner of The two Fridas. The effect is unsettling and dissatisfying; the dresses aren’t even the same.

At every curatorial step, in every room, In Her Own Image alienates the image from the artist, and the image from the political and historical setting. This approach is angled decisively towards reverence, and endorses a virtually undisguised fetishism. We are guided towards relics of her life not in the form of works that outlive her but in the form of objects that are tied back to her image, an image that, as is the case with all celebrity and fashion images, is already a dead object, revived only by the cultic worship of the fetishist. The further step taken in the revelation of such intimate items as medicine and perfume is that we might revive the image by internalising it, taking the dead woman’s effects into ourselves, having our now-comparable suffering redeemed through her. The museum is turned into a shrine, as Kahlo collected anonymous votive paintings (retablos) from the early twentieth century for a shrine to miraculous recoveries from accidents and injuries. Kahlo becomes the patron saint of the self-portrait (now selfie), the tortured artist, the long-suffering lover and wife, revered fashion icon, and empowered disabled woman. We must not think too deeply about the fact that she remained a communist and anti-imperialist throughout her adult life, and that her paintings constantly undercut her image.

Scott Robinson is a writer, academic and unionist, published in Overland, MeMo Review, Index Journal, Arena, Monthly Review, Artlink, ArtsHub and demos journal and elsewhere. He is currently associate editor at Philosophy, Politics, Critique. scottrobinsonwriting.com