The Queensland Cultural Centre (QCC) and its unavoidable concrete mass. Photograph by unknown.

Queensland Cultural Centre

Nyoah Rosmarin and Tahj Rosmarin

It seems almost too obvious to talk about the Queensland Cultural Centre (QCC). The precinct is not really that new—it was built over a decade from 1976 to 1988—and there has already been enough said about the cultural and urban imprint of Expo 88 on Brisbane. Yet still, the four blocks of concrete mass are unavoidable. In a distinctive manner, they have impacted us. We even think about the QCC when reading David Malouf’s words in Johnno:

Despite Johnno’s assertion that Brisbane was absolutely the ugliest place in the world, I had the feeling as I walked across deserted intersections, past empty parks with their tropical trees all spiked and sharp-edged in the early sunlight, that it might even be beautiful…

And maybe this is reason enough to spend some time on the QCC, not just because it is formative to us but also because it is obvious to those familiar with it.

The QCC is a set of four public buildings on Jagera and Turrbal Country: the Queensland Performing Arts Centre (QPAC), the State Library of Queensland (SLQ), the Queensland Art Gallery (QAG) and the Queensland Museum (it doesn’t really have an acronym). These uses and their immediacy to city infrastructure ensure that the precinct is an important part of life in Brisbane. However, the four buildings and their combined mass ensure a certain civicness.

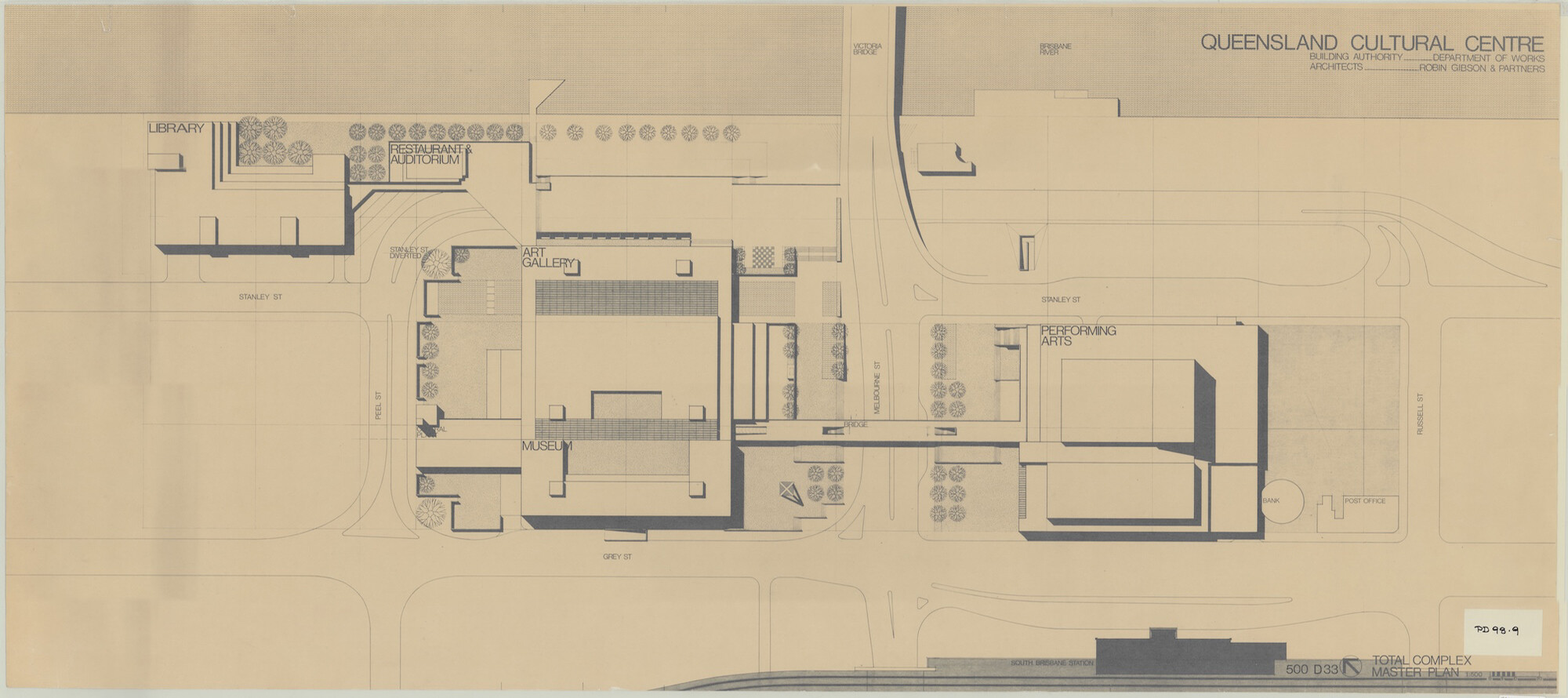

Precinct plan. The Library, Restaurant, and Auditorium are on the water’s edge at the top of the plan, while the Art Gallery establishes a riverside park and is interconnected with the Museum. The Performing Arts similarly defines a forecourt to the river and links to its siblings via a pedestrian bridge over Melbourne Street. Drawing by Robin Gibson and Partners, 1973. Courtesy of Queensland State Archives.

While a public building can be defined by its use, irrespective of its design, a civic building, for us, is defined by its impact on the city, irrespective of its use. In this way, a small house can be civic or have civicness if it has an awning that shelters the footpath, and a courthouse can lack civicness by having a fence that imposes and prescribes access. These are primary examples, but this distinction applies to all aspects of architectural design—form, materiality, siting, and so on.

There are many public buildings in Brisbane, but not many are truly civic. For us, the QCC is a clear example of a shared understanding of public good, which contributes to its civicness. It may even be the best suite of civic buildings in so-called Australia.

The singular light-concrete surface is vegetated on its fringes. Photographer and date unknown.

It is interesting, then, that the buildings themselves are almost unremarkable. From the outside, they are big horizontal boxes—long Jenga blocks placed in adjacency. Yet the particular unremarkable-ness of the QCC is also part of its civicness. The singular sand-blasted concrete walls that make up the four buildings (there are barely any separate structures, i.e. the wall’s surface is the wall’s structure) are consistent, even though they were constructed in stages. Despite their scale, their blonde uniformity ironically recesses them like they are background music.

Brisbane kitsch. It’s still there. Courtesy of Queensland Museum Kurilpa, 1986.

Pedestrian malls weave each building into one another and connect the precinct to city infrastructure—South Brisbane train station, South-East busway terminus, Southbank parklands, the Brisbane Convention and Exhibition Centre, and the Victoria, Kurilpa and Neville Bonner bridges. Along Grey Street, the windowless blocks are ruthless, with the big wall of the Queensland Museum only recessing to exhibit a semi-permanent T-Rex. And while brutal along the road’s edge—or the infrastructural edge—the volumes mediate toward the river’s edge and establish the spaces around the buildings as maybe more important than the spaces inside.

While today, one may expect a building of this significance to be more glamorous and gestural, this mass-concrete approach was not uncommon at the time. Brutalism (with a capital B) was an Architecture (with a capital A) known for its use of concrete as an affordable, quick-to-build, and “raw” material. It was prominent in the post-war reconstruction of Europe and the buildings were often administered by bureaucratic bodies or Government Architect’s Offices (GAO). These centralised design offices, somewhat haphazard as political mechanisms, enabled the delivery of public works for the public good and, importantly, without incentivised profit. Brutalist buildings became synonymous with State architecture—public housing towers, government offices, universities, and schools. Yet, ultimately, with the rise of Thatcherism (neo-liberalism) in the late 1970s, many government assets were privatised and State-operated design offices removed, marking the decline of Brutalism and the notion of the civil servant architect.

In the case of the QCC, it is no surprise that it was built on the labour of the Queensland Department of Public Works back when each state had an established GAO. Amongst others, Roman Pavlyshyn, a Ukrainian émigré and a civil servant, was essential in selecting the site, navigating the backroom bureaucracy while protecting the sanctity of the project—the public good—and ultimately awarding the winning scheme to Robin Gibson and Partners in April 1973.

The precinct, originally proposed as a single art gallery, was located in the Domain, then Roma Street, until Pavlyshyn nominated a former industrial site along the Maiwar in South Brisbane. In 1974, with an upcoming election, the Liberal Treasurer, Gordon Chalk, surreptitiously engaged Robin Gibson and Partners to develop a brief and scheme for the whole precinct with the hope of usurping the current Premier, Joh Bjelke-Peterson.

Although founded in what might be described as political sabotage, Gibson obliged and produced a revised proposal that included an art gallery, state library, performing arts centre, and museum. Chalk then publicly announced the project before cabinet approval, and with strong public support, the additional buildings were added. But the scope grew four-fold overnight, and the inflated cost of the total precinct was now a serious issue. Fortunately, the Queensland Government owned and operated a lottery corporation called the Golden Casket. With the introduction of Medicare, which freed up the Golden Casket, funds could be reallocated from healthcare to the cultural centre. Losing the lotto meant winning a gallery.

This financial and political dance is messy but not altogether uncommon in Australia—there are similar narratives in other major public works. It is no coincidence that the QCC was coined the “Brisbane Opera House” during its development. They had time and (lotto) money, but very easily could have had neither. In the end, the expanded scope of the project and its place on the riverbank meant that, due to its siting and scale, there was a predetermination of QCC’s civicness.

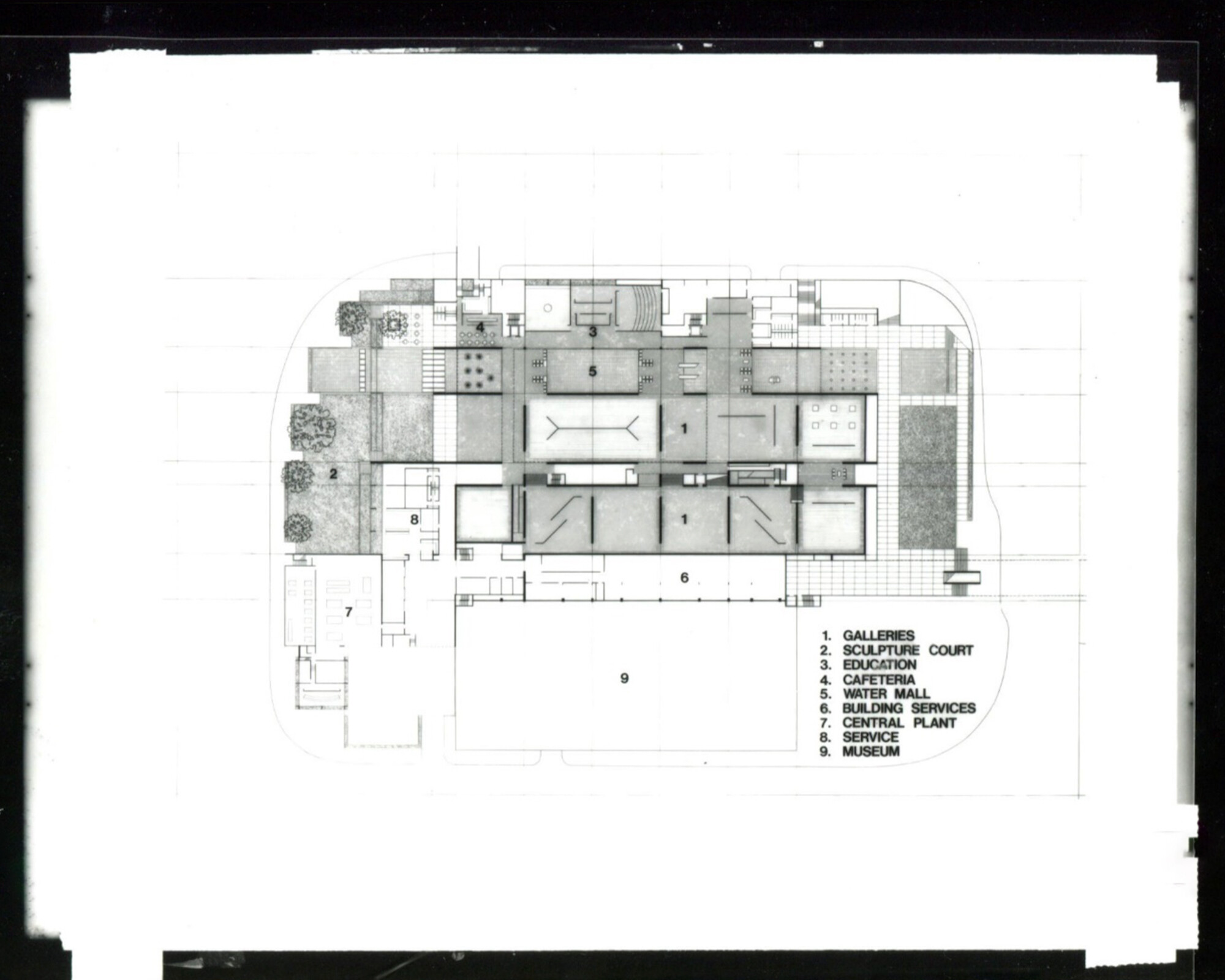

Each building is defined by a 3m x 3m grid; in the art gallery, this divides the interior into a series of corridor-less rooms. The plan rigidly organises space, but does not define how one circulates within it. Drawing from Robin Gibson Architectural Drawings and Records, UQFL638, Fryer Library, The University of Queensland, Architectural Drawings, Art Gallery, Tube A1. Courtesy of the University of Queensland.

From across the water, one may be forgiven for reading the buildings’ silhouettes as the former South Brisbane factories. The buildings’ total mass is heavy, a weight that is somewhat un-Australian and definitely un-Queensland. Their terraced horizontal profile is alien. It lacks the sheltered edge, deep eaves, and screened threshold that is typical of “inside-outside” tropical Queensland architecture. Yet what is lost in these architectural clichés is gained in capturing the QCC’s approaches to natural light, fresh air, and connection to the landscape.

The “water” mall (the “special” room in the building). Photograph by Richard Stringer, 1996. Courtesy of the State Library of Queensland.

The “water” mall, for example, is an odd double-volume gallery room and an extra-large corridor. It has natural light from tilted concrete fins on the ceiling and a shallow pond, which continues through the building like a river stream, and is an obvious link to the Maiwar. Spatially, it is an open foyer—one does not have to pay to visit—surrounded by gallery rooms. It is accessible from each end of the building, above and below, and one can walk through it on the way elsewhere without visiting an exhibition. While a grand space, this lack of prescription allows for a certain civicness—the “special” room in the building is free.

The “whale” mall. The corridor is whale-width. Photograph by unknown, 2023.

Outside the gallery, the pedestrian “whale” mall, which runs between the museum and gallery, from the city-bus terminus to the river, is equally oversized. There is a clear duality in these two malls. The repeated concrete fins make up sections of the ceiling, and in another variety of Brisbane kitsch, scale whale models hang from this ceiling. The “external” wall is cut with small apertures that permanently display their collections in a reduced version of the T-Rex on Grey Street, and the boundaries of controlled exhibit pour outside the walls into open space. As almost inversions of each other, the “whale” mall and the “water” mall are gallery-corridors and corridor-galleries, respectively, while both are “amphibious” in very different ways.

There is no one way to use the spaces of the QCC, and, in fact, one does not need to enter them at all, just like the two malls. It is as common to rest in the riverside park in front of QAG, transit through the malls, or pass by on a CityCat ferry as it is to study in the library, visit an exhibition, or watch a show. In comparison to other public precincts in Australia, QCC is rare in its doubleness as a destination and a thoroughfare. Yet, what is particular is that this doubleness occurs from inside and outside its walls—that institutional space is afforded free rein, almost the same as shared public space. This makes the precinct and the buildings possibly endless (and civic) in ways Gibson, its architect, may never have anticipated.

Mediated edges with public zones as big as the buildings. Photograph by unknown, 2017.

The QCC also shows us how inherently political architecture is. Not only because it was supported by the State and funded by the lotto, but because the design of the whole precinct—its siting, form, scale, width of corridors, ceiling heights, size of floor tiles (1.5m x 3m), relationship to the scale of the city, and so on—relates to an understanding of public good. In the same way a small house with an awning shelters a portion of the footpath, the QCC defines civicness by capturing space through design.

While, on first impression, the big blocks of concrete may seem misplaced in tropical Brisbane, their civicness has created the opportunity for publicness in this city. In the ambiguity that straddles defined use with unknown futures, civicness can be found where there is shared space for public good. The QCC, although politically muddled and environmentally problematic, is made up of good civic buildings because they almost appear out of focus, despite their obvious impact on those familiar with them. And sitting along the riverbank today, in the building’s forecourt, one only needs to look across the water to see how much things have changed.

Tahj and Nyoah Rosmarin are brothers and architects based in Naarm/Melbourne.