Sophie Cassar, Self Restraint, (archival prints), 2024. Inkjet on cotton rag. Dimensions variable. Photography: Amy May Stuart. Photo: Thomas McCammon

Sutures

Amelia Winata

It is a Sunday afternoon, and I am sitting in a public library in Melbourne’s CBD, googling “disability fetish.” Fearing discovery, I dim my screen and avoid searching images. I suspect there is plenty to be found on the topic. Tumbling down the rabbit hole of disability-associated kinks, I quickly learn of the broader umbrella term devotism—defined as “sexual attraction to disability (minor, such as missing fingers, or severe, such as blindness, limb amputation or quadriplegia).” This proclivity encompasses a slew of niche kinks with their own specific medicalised terminology, such as abasiophilia or an attraction to casts. It turns out that there are online communities that swap photographs of people (mostly women) in casts and that the kink extends to crutches and other mobility aids.

At home, I am braver: I watch a YouTube clip titled “Anna fresh SLWC with High Heels and Boots at the Hotel (Chapter 02)” that features a woman with her leg in a “Short Leg Walking Cast” hobbling around a hotel room and struggling down some stairs leading towards an outdoor pool. This is a teaser. For the full video, interested parties can head to Castplanet.com. Enticing synopses accompany the teasers and provide some narrative context: “Jessica desperately wants her ex back, but he’s currently got a girlfriend. She remembers that he has a cast fetish, so she’s got a perfect plan to get him back. Her plan is that she’s going to get a broken leg and a nice LLC that he can’t resist.” For the uninitiated, this is short for “Long Leg Cast” and, unlike the SLWC, extends all the way to the middle thigh.

Installation view of Sophie Cassar, Sutures, Footscray Community Arts, Melbourne. Photo: Thomas McCammon

For Sophie Cassar, an artist living with disability, abasiophilia is fertile ground for exploring power dynamics in the medical world. It is the subject of her exhibition at Footscray Community Arts, Sutures. Through video, photography, and artist books, Cassar chronicles the application of a cast to her leg before taking it out on the town. Although seemingly satire, these pieces would likely be a hit on castplanet.com. As many casters mention on their dedicated forums, even seeing someone in the street wearing a cast can be quite the turn-on. In fact, the most popular caster fetish material I encountered was rather pedestrian or “everyday” in nature. The same could be said of a foot fetishist encountering bare feet on social media. Posting feet pics for free is now widely considered a lost business opportunity.

Cassar sees the “struggle” itself as a fetish. An overwhelming number of casters report feeling attracted to the emotional and physical battle of navigating the world. Interviewed by Vice, Mark (not his real name) commented, “I guess I enjoy watching their struggle, the way their bravery triumphs, and how others react to that.” Rather than thinking of this sentiment as an extreme perversion of medical care, Cassar views it as a condition of the patient experience. As a patient, she has given up control of her body countless times. She has worn the Ilizarov apparatus twice, a metal structure fixed to the affected limb with pins drilled into the bone to lengthen, reshape, or hold them together. In the video and photographic works, the deep indentations left by the Illizarov frame on Cassar’s leg are visible. This more cyberpunk device is likewise titillating for many devotees due to its significant impact on patient mobility.

Sophie Cassar, Self Restraint (video documentation), 2024. Digital video, 17 minutes. Videography: Nunzio Madden. Photo: Thomas McCammon

The first work I encountered after entering the admittedly weird space of FCAC’s Roslyn Smorgon Gallery (it is more of an event hall than a white cube) is a video titled Self Restraint (2024). Here, the artist is filmed having a cast applied to her stilettoed foot and lower leg. Peeking out from under her SLWC, the viewer sees her red lacquered toenails encased in the golden bejewelled straps of her shoes. I am reminded of one comment from Piotr, a twenty-five-year-old IT programmer from Poland, who also identified as a foot fetishist: “I love how cute and vulnerable toes look sticking out from the cast with the rest of the foot hidden and immobile.” The heel, I discover, is an important aspect of abasiophilia. In many photos and (videos, the model’s non-cast foot will sport a high heel for added difficulty, and its height is often included in the video titles (the higher, the hornier). For Cassar, the Flickr account “Cast’n_heels” served as inspiration. With over seven hundred photographs, this album offers close-ups of platform heels or stilettos on the uncast feet. Stockings, another classic fetish object, often sheath both cast and foot.

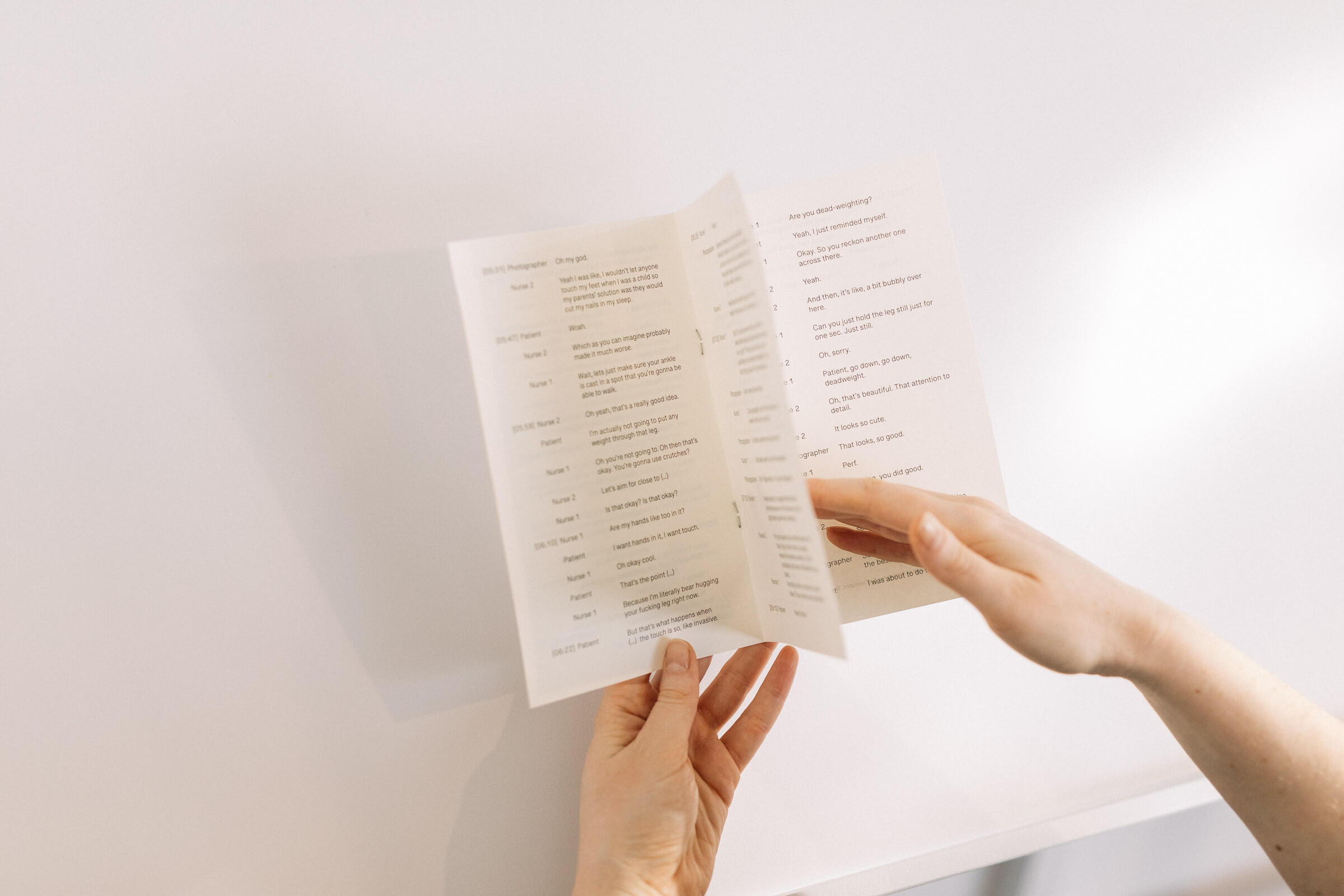

Sophie Cassar, transcript of Self Restraint. Photo: Thomas McCammon

Shot by fellow artist Nunzio Madden and shown on a domestically proportioned flat-screen TV, Self Restraint is pornographically coded. Cassar’s hospital gown gapes open to reveal her upper thigh, and her faces are cropped out or blurred. The nurses applying the cast wear rubber gloves with the fingers cut out—mimicking toes peeking out from casts. Presented without sound or identifiable subjects, the video is withholding in a way that is both frustrating and enticing. A nearby booklet that is part of the exhibition offers a transcript of the discussion that went on during the application of Cassar’s fake cast. This booklet is presented alongside Cassar’s artist books that chronicle her medical journey, as well as three paintings made with chlorhexidine, an antiseptic used for surgery sterilisation (The Well-Dressed Wound, 2024), made with the assistance of artist Clare Longley. The transcript booklet reveals a relationship that maintains a power dynamic, albeit one based on mutual consent and respect. “Is that comfy for you?” asks Nurse 1, to which Cassar responds, “Yep.” The banter thereafter is light and tinged with many moments of humour as the group discusses cast fetishism. This muddies the assumed black-and-white power construct that the muted video initially suggests.

Of course, consent is the core tenant of both sexual and medical relations. For the exhibition catalogue, local poet Autumn Royal has written a poem titled why?…after Bob Flanagan. Flanagan was a performance artist who was diagnosed with cystic fibrosis and practised sadomasochism. He famously starred in the Nine Inch Nails Video Happiness in Slavery, where he was strapped into a torture device before having his genitals and nipples clamped and crushed. For Flanagan, masochism was just as powerful as sadism. Royal’s poem characterises being part of the medical system as an endless oscillation between fear, powerlessness, deferral, and performance. “Because theatre is nothing without an audience.” “Because medical intervention creates sickness as much as it treats illness.” “Because enacting self-restraint eclipses all medical procedures requiring anaesthetic.”

Sophie Cassar, Self Restraint, (archival prints), 2024. Inkjet on cotton rag. Dimensions variable. Photography: Amy May Stuart. Photo: Thomas McCammon

The photos taken by Amy May Stuart (also all titled Self Restraint and dated 2024) complete the exhibition. Some of the images document the process of Cassar’s cast being applied. Others show Cassar and the cast in club-like settings. The latter images mimic the format of Cast’n_heels, but unlike these amateurish images, which are poorly lit, awkwardly framed, and shot against distasteful suburban decor, Stuart’s photographs are far more stylised. They look like they have stepped out of a fashion editorial. Cassar‘s pink satin dress matches her strappy gold heels, and the hard front flash recalls the porn-adjacent fashion photography of Terry Richardson and Juergen Teller. As fetish is a fashion staple, this irritated me at first. However, I remind myself that Sutures is not just about fetish or even fashion, but the uncomfortable entanglement of power and consent.

Installation view of Sophie Cassar, Sutures, Footscray Community Arts, Melbourne. Photo: Thomas McCammon

It is perhaps worth mentioning that Stuart and Cassar are active members of a community of artists advocating for disability rights. Stuart regularly beautifully documents friends’ exhibitions (many artists choose to have her shoot their exhibitions on film to complement the standard documentation commissioned by institutions). Cassar centres this relationship and community as a methodology for subverting the subjugation or alienation often associated with being a patient. Some of the photographs were shot at Flippy’s, a queer bar on Sydney Road run by Amy Parker and Em Lipschitz, which has become Melbourne’s resident safe space for LGBTQI+-coded speed-dating, karaoke, and trivia nights. Indeed, if we consider the friends and collaborators credited in Sutures by Cassar—Madden as cinematographer, Royal as catalogue poet, Longley as painting assistant—what becomes clear is how Cassar decentres herself as a part of a support network. Credits are also extended to Katie Ryan (who I think I recognise as one of the artists in Cassar’s video Self Restraint), who hosted the 2022 symposium Art and Ableism, featuring Cassar and other artists with disabilities, and Jane Trengrove who co-organised the symposium with Ryan and who mentored Cassar during the production of Sutures. There is also Sam Petersen, who was recently a part of the exhibition Yucky at ACE in Adelaide alongside Cassar and five other artists who identify as disabled, neurodivergent, or chronically ill. Critically, Petersen has been a tireless activist for disability rights and, most recently, has been a key voice in opposition to the federal government’s proposal to reform the NDIS, which disability activists are saying will have devastating effects on communities of people with disabilities. Their activism and place within a network of like-minded creatives represent a rewriting of dominant narratives around the disabled body as powerless.

Sophie Cassar, Self Restraint, (archival prints), 2024. Inkjet on cotton rag. Dimensions variable. Photography: Amy May Stuart. Photo: Thomas McCammon

In devotism, the devotee—the person with the disability fetish—is the subject. Through my cursory research, there is no analogue term for the person with the disability by whom the devotee is aroused. They are cast (pardon the pun) as the object. No surprises here. What is just as obvious, albeit often not acknowledged, is that this subject/object dynamic reflects the ableism in mainstream society. As Katie Ryan stated in the Art and Ableism symposium, able-bodiedness is described as “the lack of disability and particularly relates to the capacity to work.” Putting aside for a moment humanity’s obsession with work and productivity, in Sutures, Cassar goes to great lengths to reorganise the working body as working bodies and a working network. Thus, the disabled body is not necessarily an object to/of the able-bodied subject (as much devotism discourse would have us believe). In fact, it is not strictly either subject or object but a well-organised, self-determined organism.

Amelia Winata is a writer and curator based in Naarm Melbourne. She is currently Curator at Gertrude Contemporary. She recently completed a PhD in Art History at the University of Melbourne.

This review was made possible thanks to the generous support of Meridian Sculpture.