Albrecht Dürer, Melencolia I (detail), engraving, 1514. Archives and Special Collections, University of Melbourne. Grace Wood, Permanent Palimpsest (detail) 2024 at Bundoora Homestead Art Centre. Photo: James Henry.

Grace Wood, Permanent Palimpsest; Albrecht Dürer’s Material Renaissance

David Wlazlo

Like a moth to a flame, I was drawn this week to an exhibition at Bundoora Homestead Art Centre. Grace Wood’s work Permanent Palimpsest (2024) has just the thing I’m a sucker for: some kind of reference to the history of writing, especially when used to visualise how meaning, significance, and inter-textual connections are generated. In this case, the word “palimpsest” provided the lure.

I don’t generally lurk on the outskirts of the artworld waiting for such signs, but when I see “palimpsest” I am generally interested, piqued even. Because—hand on heart—I am a ’90s critical theory, cultural studies, and philosophy tragic. After growing up intellectually in an age when hypertext (in some cases literal “http”) seemed to some over at ctheory.net to be a radical cultural moment, what use was the figure of the palimpsest to be put to now? What twenty-first century inter-textual weaving was I up for?

Grace Wood, Permanent Palimpsest (detail) 2024 at Bundoora Homestead Art Centre. Photo: James Henry.

A paleographic palimpsest begins its life historically as a manuscript that has had its text partially—or incompletely—deleted and written over with a second, perhaps un-related, text. First employed in the long stretch of time before the printing press, scribes would erase text and then add a second script to a page of parchment due to the latter’s scarcity. Sometimes the page would be turned sideways. Original manuscripts—sometimes hundreds of years after they were produced—were erased, cut up, re-ordered, and re-bound. After time, the chemical traces of the original ink would reappear, producing a palimpsest. A practice driven by frugality—writing material being expensive and scarce—the end result would be a page of layered writing, perhaps between lines or perhaps with added new lines on top.

Since 1845, when Thomas De Quincey first wrote of it as a figure of thought, the palimpsest has been used to describe a myriad of processes and situations that rely on inter-textual, inter-disciplinary, non-hierarchical methodologies. The palimpsest can even be said to be a trace of the attempted murder of ideas, only for them to be magically (chemically) resurrected later. Anything from the way cities evolve to the way intersectional subjectivity is created can be said to involve a “palimpsestuous” reading of styles, influences, and meanings. Even the “mystic-writing pad” described by Sigmund Freud in 1925—a device that could be written on, quickly erased, yet leaving a trace on the wax underneath—could be said to be a kind of palimpsest-like device. Freud connected the writing on top with the conscious mind, and the traces underneath as the inescapable unconscious. The relatively straight-forward material practice of recycling writing material led to wide-ranging metaphorical fecundity. A palimpsest is a material that is written on while retaining traces of past writings. This material—strictly speaking—is a manuscript or book. But, over time, the idea has expanded to include many material traces that emerge underneath and around other, newer traces.

With this heavy flutter of ideas under my bonnet, what was I expecting when I finally made it out to Bundoora?

Grace Wood, Permanent Palimpsest, 2024 at Bundoora Homestead Art Centre. Photo: James Henry.

Wood’s Permanent Palimpsest consists of a piece of material hanging curtain-like from the ceiling. The cloth has a pink flesh-toned colour, and has smaller patches of cloth—either digitally printed with images or embroidered—sewn on to the background haphazardly. Some of these sewn-on patches are quite large while others are very small: they look like islands or regions of collage against the light background. There are printed facsimiles of postage stamps, actual metal badges, and the occasional necklace or chain linking elements together. There is a constellation of sequins sewn into the background fabric. The piece itself hangs about half a metre away from the wall at the back of the space so there is the opportunity to walk behind the work, although this cannot be done comfortably.

Grace Wood, Permanent Palimpsest (detail) 2024 at Bundoora Homestead Art Centre. Photo: James Henry.

The patch-like fabric images sewn onto the work are of Australian postage stamps, stamp albums, small wooden toys, images of hands with various bandages, some medical equipment, images of nurses, and a newspaper article about the Bundoora Homestead itself. These fragments collaged onto the hanging textile are at once quite cryptic and disturbingly specific. What thread can be woven between them? A wall label describes the artwork as a response to the history of the Homestead: built at the end of the nineteenth century as a mansion for a horse breeder, the building eventually became a convalescent home for returned soldiers after the Great War. Bundoora Homestead continued to care for the unwell until the 1990s, before being turned into the Art Centre that it is today. The cryptic imagery of the piece—the postage stamps, the wooden toys, the injured hand—are all references to the history of the place as an institution. The parkland, the rudimentary trades set up to help those suffering from the effects of war. Collecting stamps and making wooden toys were part of the treatment for those at Bundoora, according to the texts in and around the work.

Grace Wood, Permanent Palimpsest (detail) 2024 at Bundoora Homestead Art Centre. Photo: James Henry.

It’s all starting to make a bit more sense after reading. Although in some ways it also seems to make too much sense: the anecdotes about stamps and wooden toys—quotidian in themselves as a therapeutic everyday—make their presence felt in the work through the visual presence of stamps and wooden toys. With minimal interpretation, there is a simple connection between the source material and the artist’s representation.

I don’t necessarily mean simple and direct in a bad way. The artwork is illustrative, layering images from the grounds and the history of the various medical institutions that called this place home over the last 120 years. Going outside, you can imagine yourself being rolled out in a wicker wheelchair to get some air, completely oblivious to all forms of figuration and metaphor. Pushed away from the literary and into the sun. Indeed, while I came with visions of a palimpsest, to me Wood’s work seems almost topographical, a sort of mapping together of clues, tracing lines with necklaces and marking events with sequins and pinned badges.

Grace Wood, Permanent Palimpsest (detail) 2024 at Bundoora Homestead Art Centre. Photo: James Henry.

Perhaps, then, the site of the Homestead is my sought-after palimpsest, while Wood’s work is a topographical map overlaid with references to the site’s history? There is the site’s initial theft through colonial violence, legal and literal, where the sovereignty and land management of the Wurundjeri Woiwurrung Indigenous custodians was whitewashed by settlers from the early nineteenth century. There are also the many institutions that have called the Homestead home: the family institution of the wealthy horse-breeder John Matthew Vincent Smith (1857–1922), the medical facilities housing the mentally unwell and later the discovery of the medicinal qualities of lithium by Dr John Cade (1912–1980). Each of these layers leaves tangible traces, such as the scarred trees on site and the grave of a horse bred by Smith. These backgrounds and histories form part of the cultural institution of the Homestead as the art centre it is today. There is a floor sheet and essay, however, that also links the work to the artist’s labour (all of the work was sewn by hand), the experience of family mental ill-health, the passing-down of inter-generational fabrics, the difficulties of making work while parenting. These are all layered into the work and layered onto the site, its history, and my rather elaborate and fanciful expectations. This seems like art for the community, not necessarily me. When so much artwork today plays to the academy, I think this is a strength.

I was drawn to this show by the metaphorical richness of the palimpsest, but I end up thinking about how material culture seems to transcend such figurative language. Well, perhaps not transcend… unless it transcends downwards to ground such broad and fertile ideas.

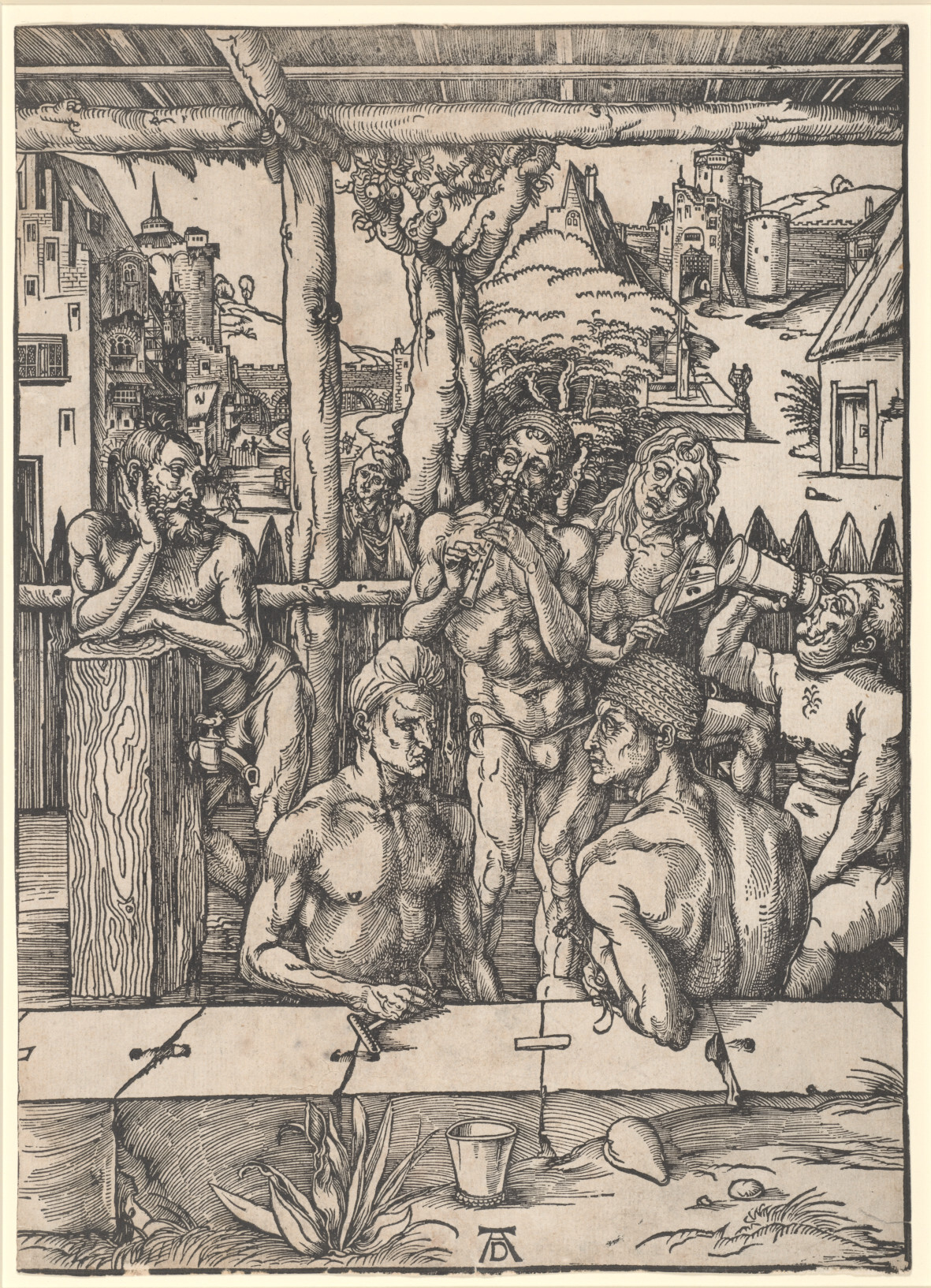

Albrecht Dürer, The bath house, c.1496, woodcut. Archives and Special Collections, University of Melbourne. Gift of Dr J. Orde Poynton 1959.

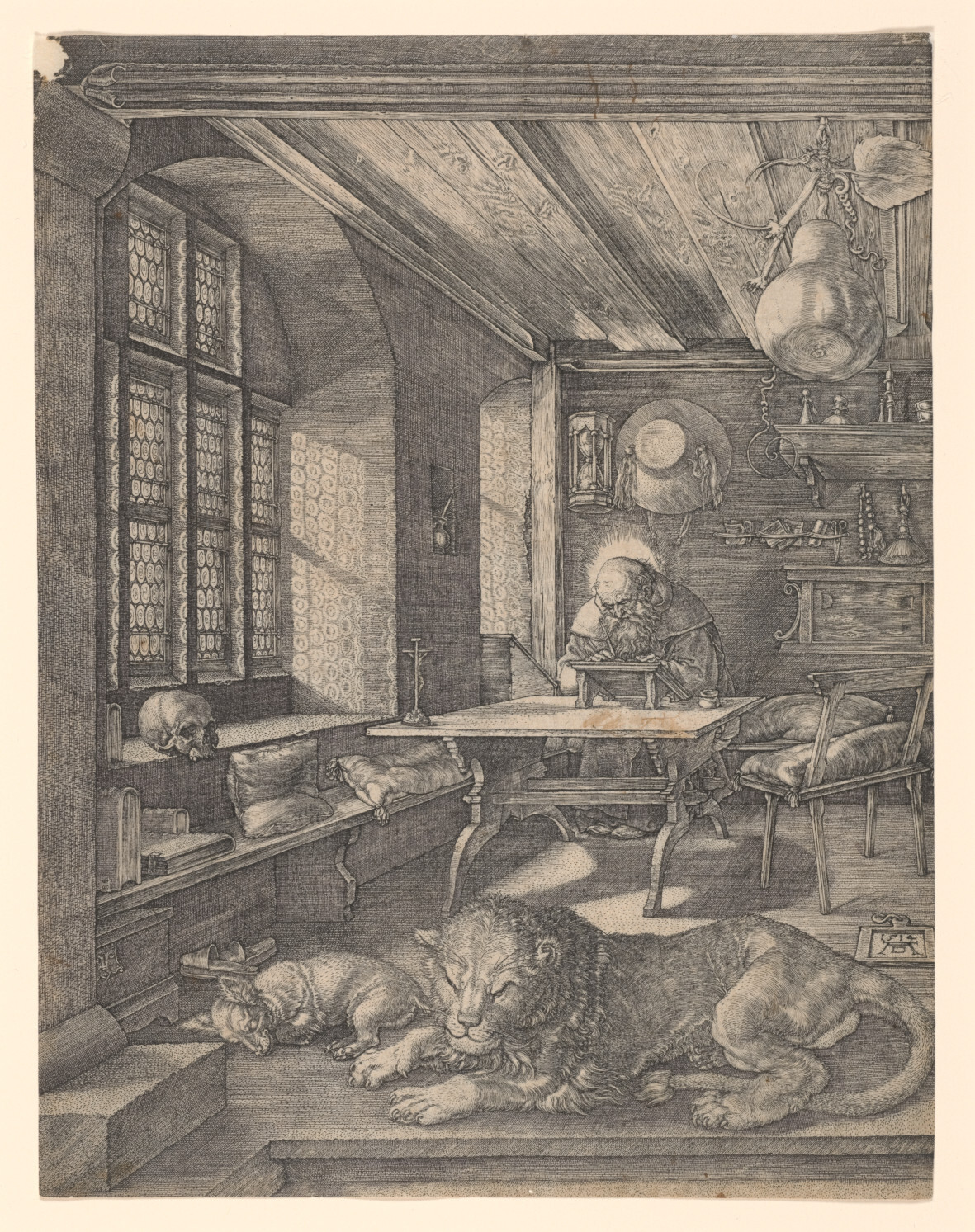

Across town, a literal, non-figurative palimpsest is on display in an exhibition of engravings by Albrecht Dürer at the University of Melbourne’s Arts West gallery. Albrecht Dürer’s Material Renaissance features a collection of over 90 works by Dürer and his contemporaries sourced from the University of Melbourne’s and the State Library of Victoria’s collections. The works range from very famous engravings such as Melencolia I (1514) and St Jerome in his Study (1514) alongside work produced by peers such as Hans Sebald Beham (1500–1550) and Michael Wolgemut (1434–1519). There are also manuscripts, early printed books, and a page from a Gutenberg bible. I’m particularly fascinated by the printed Latin textbook Elegantiae linguae latinae (1534) by Lorenzo Valla, whose open title page shows the various writings, doodles and scribbles of multiple past owners of the book.

Installation view of Albrecht Dürer’s Material Renaissance, Arts West Gallery, University of Melbourne. Photo: Drew Echberg.

These precious objects are arranged throughout the darkened, multi-room exhibition, and it seems beautifully calm and light-spirited compared to the rush of students outside. The exhibition is part of a research project into the material culture of Dürer’s world via the objects and materials represented within the works as well as the works themselves, which are both artworks and objects to be produced in edition, bought, sold, and traded. The exhibition is part of a collaboration or cross-institution research project, with exhibitions and public programs being held at the University of Manchester as well. At the University of Melbourne, Albrecht Dürer’s Material Renaissance is being led by curators Jenny Spinks, Matthew Champion, Shannon Gilmore-Kuziow, and Charles Zika, with help from Jenny Smith.

Albrecht Dürer, Melencolia I, engraving,1514. Archives and Special Collections, University of Melbourne.

The works themselves most likely need no introduction. Dürer’s technical skill is matched by a pictorial ease and lightness, and his contemporaries seem also to revel in the newly developed printing industry. There is a wealth of objects represented in the works, just as the works now represent the wealth of the collections from which they are drawn. I’m particularly intrigued by the wooden joinery across all the images. Have you ever tried to draw wood-grain? You feel like you’re making it up as you go along. But within these works I sense a kind of joyous, light-hearted embrace of early industrial printmaking. There are lofty ideas and allegories, for sure, and there is the Renaissance interest in science and the knowledge gleaned from pagan antiquity. This, of course, is matched by the strange faith and interest in astrological and alchemical ideas. But there also seems to be an enjoyment of picture-making. A lightness and pleasure that seems to manifest in the artist trying to cram as many different objects into the picture plane as he can. There’s no monocultural lens through which to view the world of Nuremberg in 1500.

Albrecht Dürer, The bath house, c.1496, woodcut. Archives and Special Collections, University of Melbourne. Gift of Dr J. Orde Poynton 1959.

No monocultural lens, eh? Perhaps the process of looking at history—writing, thinking, and learning it—is a palimpsest, a layering of contemporary ideas over a past that may remain hidden for now, only to be revealed later? Although this idea is anachronistic—I can’t assume that anyone in sixteenth-century Europe saw culture as overlaid text—don’t we always bring our own layer to add to whatever we’re looking at? Aren’t there already a myriad of overlaid voices speaking over the top of each other? This is such a modern idea, and I can’t seem to escape its gravitational pull.

Albrecht Dürer, Coat of arms with a skull, 1503, engraving. Archives and Special Collections, University of Melbourne. Gift of Dr J. Orde Poynton 1959.

This is the gravitational pull that makes me view medieval culture through the candour of Ingmar Bergman’s The Seventh Seal (1957); that pushes me to recognise the modernity of the 1460 woodcut fragment Calvary on show at the Dürer exhibition (by an unknown artist). This is the force that tells me to stand behind Grace Wood’s work and admire the shadows through the semi-transparent material, and to see post-WWI PTSD through Pat Barker’s novel Regeneration. It’s the same force that makes me think there’s a palimpsest alongside the Dürer prints: I have a feeling, now that I’m away writing this, that I completely made that up. There are certainly palimpsest-like things, but I am now not so sure. Go see the shows and prove me wrong. The material culture will bring these figurations down to earth.

David Wlazlo is a writer who lives on Wathaurong country, Geelong