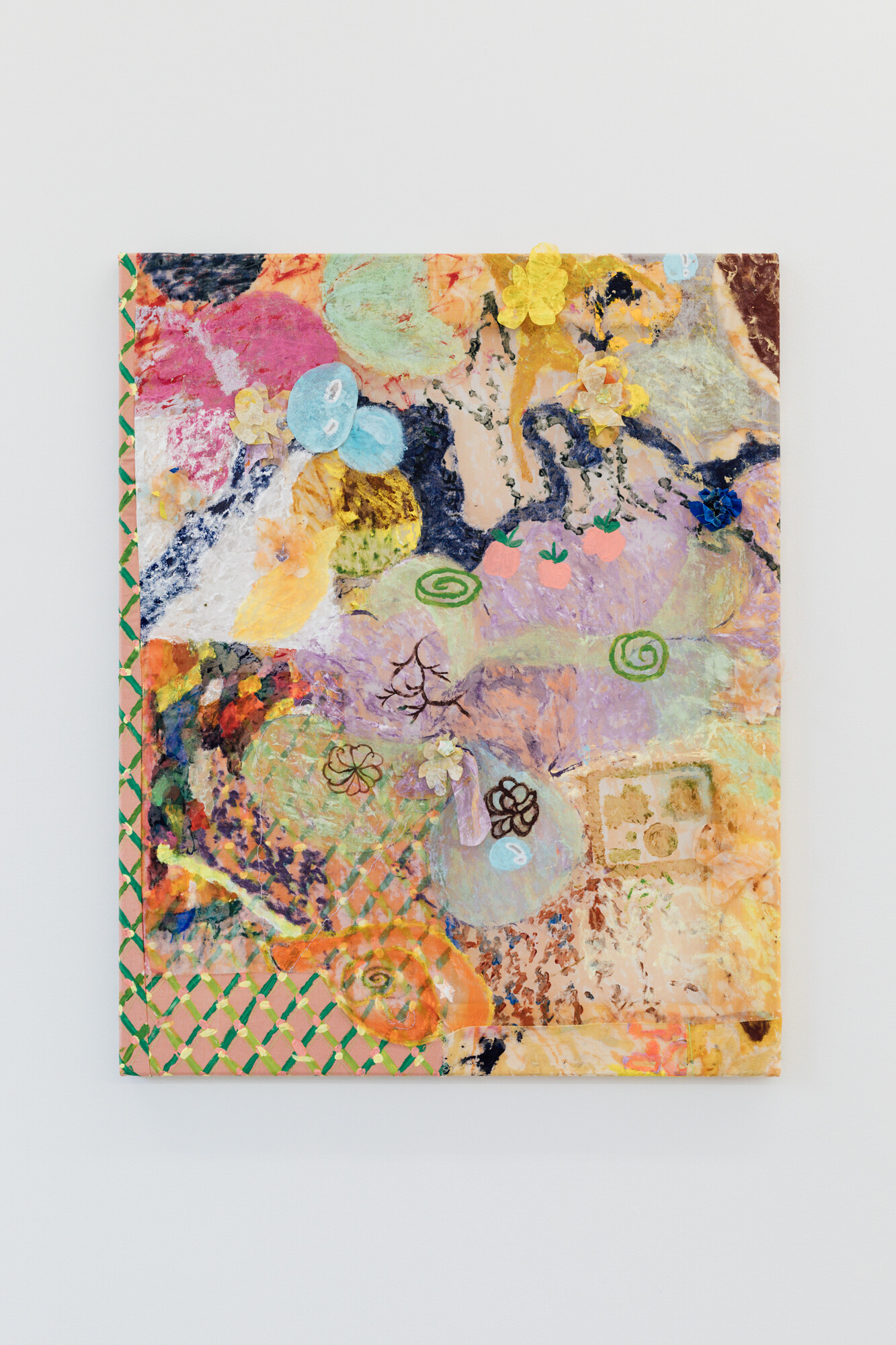

Installation view, Jemi Gale, every painting has a friend, Mary Cherry, Melbourne, photo: Lauren Dunn

every painting has a friend

Amelia Winata

Honk if the words “collaboration,” “participatory” or “care” hurt your soul a little bit. You’re not alone. Lately, art discourse has been awash with tepid manifestos pertaining to the politics of care and suggestions for how to be a collaborator in the arts. Commentators espouse the virtues of creating boundaries in the workplace, being a good ally to marginalised peoples and saying “no.” In theory, these guidelines are reasonable. That is, until we realise how quickly this discourse is absorbed into the fabric of the institution, morphing into platitudes and empty virtue signalling. The result are squeaky clean diversity KPIs that have little to do with changing organisational culture. Which is not to say that a focus upon representation and well-being in the arts is useless. Rather, that these focuses have rapidly shifted over to a spectacle performed at the expense of those whom they purport to serve. There are, for example, broader organisational mandates, such as designated First Nations roles, advertised as full time, that fail to consider the work that many First Nations arts workers undertake external to the office. I’m also reminded of participatory works in major organisations like the NGV, including Yoko Ono’s nauseating My Mommy is Beautiful, where crowds were invited to write a note about their mother and affix it to the wall. This was little more than a publicity photo opportunity that made visitors feel warm and fuzzy and offered the NGV serious savings on material costs. We seem to have slipped into care-core-cringe.

Jemi Gale, pig sounds are associated with emotions, 2024, acrylic paint, oil stick, Lululemon clothing tag, pig drawing on paper, double strength Lacteeze blister pack foil, sunflower petals, hair, canvas, 76 x 247cm, photograph: Lauren Dunn.

A palate cleanser comes in the form of Jemi Gale’s every painting has a friend at Mary Cherry in Collingwood. Touted as an exhibition about friendship, every painting has a friend is so low impact as to be a welcome relief to the politics of care-core that we are forced to dodge in our curated lives. Here, Melbourne-based painter Gale has invited friends or people whose practices she admires to include works or to collaborate with her on single paintings. The other artists in the exhibition are Rumer Elisabetta Guario, Masato Takasaka, Lily Golightly, Jess Tan, Luyan Zhang, Victoria Todorov, Hana Pere Aoake, Matilda Davis, Yusi Zang, Samantha Axiak, Jana Hawkins-Andersen, Luci Avard, and Naoise Halloran-Mackay. Only one work in the show is by Gale alone. Titled pig sounds are associated with emotions (2024), it includes a triptych of pigs hidden amongst an abstract expressionist composition. While at first glance the exhibition concept appears to participate in care-core-cringe, self-identifying as a show that “explores friendship-driven practice,” it is also deeply connected to the less corporate friendly theme of loneliness prevention. Only in recent years has loneliness been labelled a “pressing global health threat” (the equivalent, apparently, of smoking fifteen ciggies a day), but possibly due to its alignment with disease, few have connected loneliness as occupying the other side of friendship’s coin. every painting has a friend eschews virtue signalling in favour of an actual representation of how we approach our relationships. Which is: incoherent, weird, and with varying levels of intimacy.

What do I mean by this? Well, to begin with, the line-up of collaborators seems random, and there is little that visually unites these works. I didn’t know Gale was friends with Masato Takasaka. Or Yusi Zang. But then it’s also none of my damned business. These are relationships that are lived, not performed. For their part, Takasaka and Zang have included solo works. The typically obtuse Takasaka assemblage includes a can of Japanese coffee and a tiny John Nixon monochrome the size of a match box (Yet Another Propositional Model for the EVERYTHING ALWAYS ALREADY-MADE STUDIO MASATOTECTURES MUSEUM OF FOUND REFRACTIONS (1999-2024) Yes, You Kant After Duchamp! (2024)). Zang’s assemblage, sailing boat (2024), is a leaf from a Mother in Law’s Tongue plant sandwiched between two plaster cornices. I imagine Gale telling these artists to simply put in what they want, drawing on a level of trust that comes only with familiarity.

Masato Takasaka, Yet Another Propositional Model for the EVERYTHING ALWAYS ALREADY-MADE STUDIO MASATOTECTURES MUSEUM OF FOUND REFRACTIONS (1999-2024) Yes, You Kant After Duchamp!, 2024, mixed media, enamel and acrylic on canvas, cardboard, foam-core, found objects, self-adhesive vinyl on found packaging, 92 x 35 x 22 cm, photograph: Lauren Dunn.

Yusi Zang, sailing boat, 2024, plaster cornices, snake plant, 10 x 39 x 39 cm, photograph: Lauren Dunn.

Then there are the works that Gale has collaborated on with friends, the links between which are just as heterogeneous as those between Takasaka’s and Zang’s works. And, just to clarify, I think this is a good thing. For tiny sprinkles of emotion (2024), Gale painted a work that she then sent to Jess Tan in Perth, who added to the work before cutting it up, reconfiguring it and posting it back to Gale. best people (2024), an organza painting that contains a four-leaf clover, is made with Naoise Halloran-Mackay. It is my favourite work in the exhibition. The shamrock signals a degree of reserved hope amongst the depravity of 2024 and puts a silly little smile upon the viewer’s face when they finally realise what they are seeing. The layers of organza are messily smeared with nail polish, an act of girly kitschness.

Jemi Gale and Jess Tan, tiny sprinkles of emotion, 2024, acrylic paint, oil paint, cotton scraps, holographic beads, cotton thread, paper star, coloured pencil, silk, 76 x 61 cm, photograph: Lauren Dunn.

Jemi Gale and Naoise Halloran-Mackay, best people, 2024, oil paint, nail polish, shamrock, collage, organza, handmade wooden frames, 76 x 61 cm, photograph: Lauren Dunn.

Mary Cherry has been open since 2021. Run by collector-turned-gallerist Helen Newton-Brown, it has only ever opened sporadically and been dependent upon an erratic exhibition program. It is also only open three days a week. For all intents and purposes, it is a commercial gallery, and I’m told that it is moving to Rupert Street, Collingwood, near Sullivan and Strumpf. This is perhaps a signal of its desire to formalise. But, for now, Mary Cherry—on the ground floor of a small commercial lease that was probably designed to be an office—is an appropriate venue for an approach that sits outside of the mainstream of collaborative art making.

While there is a delightful lack of coherence between the pieces exhibited, Gale’s hand and aesthetic is still very present throughout. This is possible because the messiness is her aesthetic, and this is also why the show wouldn’t work so well in a more polished exhibition space. If this were 2020, I might describe Gale’s style as “grotty girl adjacent.” It has a self-consciously crude and chaotic aesthetic that will do its darndest to resist any possibility of institutional containment (though, if history tells us anything, it is that eventually everything is tamed by the institution). Alas, Naarm—and indeed, the inventor of the grotty girl label Cameron Hurst—have firmly left that epithet in the past, along with any discussion of covid lockdowns or Tristen Koenig (our new small time criminal art worker obsession is Iain Charles Dawson, the former gallery director who stole Archibald touring ticket sales). In other words, there could be a more updated way of describing Gale’s aesthetic that perhaps also includes her collaborative logic that bisects the establishment.

Rumer Elisabetta Guario, apple, 2024, chicken wire, papier mâché, sand, acrylic paint, 65 x 43 x 49 cm, photograph: Lauren Dunn.

I cast my mind back to Christopher LG Hill’s 4th/5th Melbourne Artist Facilitated Biennial, which was staged within Endless Circulation, the 2016 TarraWarra Biennial, curated by Helen Hughes. A biennial within a biennial, Hill’s intervention undid the institutional logic of TarraWarra by inserting the works of lesser-known artists, many of which were quite ephemeral, with little to no conceptual cohesion between each piece. What’s more, Hill essentially chose his friends to exhibit, including Lewis Fidock, Aurelia Guo, and Liam Osborne. The works were subversive and, unlike the rather desperately aspirational mode of relational aesthetics à la Rirkrit Tiravanija, evidently did not feel a need to address the idea of “friendship.” Famously, Zac Segbedzi included a painting of his then-estranged father Daniel Besen, the heir of TarraWarra. Hill’s anarchic approach also refused to comply with the conflict of interest guidelines that establishments often use to maintain transparency.

To be sure, all this friendships stuff is a bit cute. But cute is a precipice that never quite gives way. In Miranda Kerr as Cicciolina (2024), a collaboration with Victoria Todorov, Gale has doodled pink cartoon characters, including local hero Bluey, over a hypersexualised painting of Kerr as porn-star-turned-MP Cicciolina. The juxtaposition of the erotic with the cute is jarring and perhaps sinister, although also quite funny. Ultimately, it’s the product of two friends enjoying themselves in an unconventional exquisite corpse. You can choose to get on board or not. These girls don’t care.

Installation view, Jemi Gale, every painting has a friend, Mary Cherry, Melbourne, photo: Lauren Dunn

If the politics of care has somehow been conflated with identity as cultural capital, and if it has also now been neatly folded into the neoliberal structure, then perhaps the more anarchic approach modelled by Gale in every painting has a friend is preferable. Friendship should be and is a methodology that upholds much of the art world. But these relationships often don’t make sense to the onlooker. Some appear downright weird. Who is the Martha to your Snoop? The Bert to your Ernie? Buddies come in all forms, and the complex tapestry that is Gale’s friendship circle is energising in its surprises.

Amelia Winata is a writer and curator based in Naarm Melbourne. She is currently Curator at Gertrude Contemporary. She recently completed a PhD in Art History at the University of Melbourne.