Visitor viewing Cats & Dogs on display at The Ian Potter Centre: NGV Australia from 1 November 2024 to 20 July 2025. Photo: Eugene Hyland

Cats & Dogs

Cameron Hurst

Two distinct positions dominate discourse about art, animals, and humans today. One holds that human exceptionalism has led to centuries of oppression of non-human animals, and that this hierarchy is the product of Western, post-Enlightenment epistemologies and capitalist economic systems, which propagate corrosive, power-hungry individualism and ecological devastation. The paragon of this position, eco-feminist philosopher Donna Haraway, exhorts us to resist monotheistic cultures, Homo sapiens tyranny, and blind faith in techno-fixes for the climate crisis. To survive (and indeed thrive) in the Anthropocene, she says, we need to draw on Indigenous, queer, and feminist modes of being. We must sustain more equitable relationships with our human and more-than-human kin—seek to “stay with the trouble” and “romp in multicritter humus,” whatever that means. That’s one approach. The other is on display in the NGV’s Cats & Dogs. It goes something like: Woof woof! Meow! Aren’t our little fur babies beautiful?

Installation view of Cats & Dogs on display at The Ian Potter Centre: NGV Australia from 1 November 2024 to 20 July 2025. Photo: Tom Ross

Installation view of Cats & Dogs on display at The Ian Potter Centre: NGV Australia from 1 November 2024 to 20 July 2025. Photo: Tom Ross

Cats & Dogs presents more than 250 cat and dog-related artworks and design objects on the top floor of the Ian Potter Centre in Fed Square. Outside the gallery, Memo editor Amelia Winata’s chihuahua Kenneth appears across the show’s royal blue promotional materials; his bulging eyes and slightly anxious visage are instantly recognisable (there is no conflict of interest here, as this author has no working relationship with Kenny). Inside, in the very first rooms of the exhibition, curators Laurie Benson and Imogen Mallia-Valjan enforce a clear divide between the animals, with cat artwork on one side and dog artwork on the other. The final section consists of a plentiful salon hang, with decorative objects interspersed amongst paintings and works on paper. This is followed by an interactive room in which the public can upload images of their own pets and see them projected onto the walls inside gilded frames.

The show is organised around twenty jaunty themes, such as ‘Bad kitty’ and ‘Bad dog, no!’ Every work included is from the NGV’s collection, and as a whole, they share few historical, material, or aesthetic links—aside from representing cats or dogs. There are films, linocuts, ceramics, and one example of moderately disturbing taxidermy. There is Art Nouveau, Art Deco, ASMR, and Tibetan divination. Celebrated local and international artists Garry Namponen, Pierre Bonnard, Grace Cossington Smith, Hulda Guzmán, Lionel Lindsay, and Jeff Koons all make an appearance. There is something here for everyone—and no one in particular.

Installation view of Cats & Dogs on display at The Ian Potter Centre: NGV Australia from 1 November 2024 to 20 July 2025. Photo: Tom Ross

Installation view of Pet Portrait Gallery on display in Cats & Dogs at The Ian Potter Centre: NGV Australia from 1 November 2024 to 20 July 2025. Photo: Eugene Hyland

Because the NGV has an excellent collection, many excellent works are on display. Take the painting by French Rococo artist François Boucher (1703-70), of whom the critic Diderot once said, “That man is capable of anything—except the truth.” Boucher’s Le Panier Mystérieux (The Mysterious Basket) (1748) is an ovoid pendant oil painting of a romantic encounter between a shepherd with rippling muscles and a porcelain-skinned, rosy-cheeked shepherdess. She is slumbering prettily amongst some ruins in a lush, Arcadian garden, wearing a low-necked, satiny gown adorned with bows. Her feet are bare and very clean. He has tiptoed over to her to make a delivery: a wicker basket of fresh flowers, with a love letter tucked beneath an orange blossom. Ooh la la. The shepherdess is watched over by a faithful doggy, hence the inclusion in the show (according to the wall text, this dog symbolises fidelity and loyalty). It’s the apotheosis of eighteenth-century aristocratic froth, a painting that sparks the conflicting desires to sigh away an afternoon exchanging tender kisses with a lover in a park or drop a guillotine on someone’s neck.

The Mysterious Basket is one of a group of four oval-shaped pastoral paintings by Boucher that a mysterious Monsieur Perinet commissioned in the mid-eighteenth century. Two are in the NGV’s collection, acquired simultaneously under Patrick McCaughey’s directorship in 1982. This is also the year that impresario Paul Taylor curated Popism at the NGV, and we can imagine him encountering these new acquisitions as he entered the bunker; the cover of the Spring 1983 edition of Art & Text magazine (edited by Taylor) features the gallery’s other Boucher painting, titled An Agreeable Lesson (1748).

François Boucher, The Mysterious Basket (Le Panier Mystérieux), 1748, oil on canvas, 92.7 × 78.9 cm, National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne. Purchased through The Art Foundation of Victoria with the assistance of Coles Myer Ltd, Fellow, Mr Henry Krongold CBE and Mrs Dinah Krongold, Founder Benefactors, and the Westpac Banking Corporation, Founder Benefactor, 1982. Photo: National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

Compared with The Mysterious Basket, An Agreeable Lesson is the sexier painting. Boucher drags out a shepherd and shepherdess again; but this time, they’re both wide awake, bodies entwined, undertaking a little “flute lesson.” The presence of a bearded goat in the foreground, with beady eyes staring out knowingly at the viewer, hints at more carnal activities. (This painting is not on show in the Ian Potter; Cats & Dogs & Goats would have been a bit unwieldy.) On one level, An Agreeable Lesson seems like a funny choice for the cover of Art & Text, a decidedly contemporary art publication. However, Taylor and his collaborators clearly recognised that, firstly, Boucher is goated, and secondly, his work could be repurposed for their own means.

For Art & Text, the painting is presented without a frame on a stark white minimalist backdrop. The magazine title is printed above the image in a non-Rococo sans serif. This stylish recontextualisation of a work by an artist of notorious courtly excessiveness stakes a claim: this painting is relevant, albeit obliquely, to the magazine’s readership. Art & Text had cultivated a small, cultish, mostly Melbournian community committed to French postmodernist theory, offering English translations of major theorists as it sought to debate the state of Australian art. This issue of the magazine includes an early publication of Jean Baudrillard’s gnomic essay on simulacra, wherein he riffs on the idea that we live in a hyperreality populated by images formed from copies which have no original. Disneyland, he proposes, with its “play of illusions and phantasms,” functions as the perfect model of “all the entangled orders of simulacra.” The theme park is “presented as imaginary in order to make us believe that the rest is real.” Baudrillard’s text is printed alongside a selection of eighteenth-century works from the NGV’s collection. One page features Boucher’s The Mysterious Basket, with its devoted hound. Why all this Rococo in the desert of the real?

Installation view of Cats & Dogs on display at The Ian Potter Centre: NGV Australia from 1 November 2024 to 20 July 2025. Photo: Tom Ross

Perhaps because Boucher and his contemporaries were artists of pastoral simulacra, capable of anything except the truth, proliferating whimsical images as shared political realities disintegrated. Or perhaps Art & Text was making an ironic joke directed at those who were skeptical of French theory’s esotericism: appropriating images from Francophone culture’s most decadent period was a doubling-down of allegiance, a troll. Maybe they just liked shepherds and shepherdesses. The Art & Text enterprise shows how the act of critical re-framing of art and art history can make you see familiar work utterly anew, or new work in surprising dialogue with the past. (An aside: Edie Duffy’s Basket with Screen is like an eBay Boucher. Don’t skip her Caves show.)

I take you on this extended Arcadian detour as I think it offers a lesson—an agreeable lesson—in how generous institutional collection access can give artworks new contexts and publics. Cats & Dogs does this to some degree, but the framing essentially solicits a kind of Where’s Wally mode of looking, prompting us to search in the corners of artworks for pets. It’s fun, but not particularly thought-provoking. And, to risk stating the obvious, the point of a public collection is that it’s for the public. This leads us to one great scandal of Cats & Dogs: the fact that it is a show of works from the public collection that we must pay to enter! Some might call that a dog act: akin to paying to look at art in your own living room. (There is a family ticket discount—perhaps an opportunity to test out the limits of Haraway’s kin theory in practice?) Ok, sure, art workers need fair pay, and the Victorian state government, currently in a debt hole that goes far deeper than any Metro Tunnel dig, doesn’t seem to be in a great position to bolster the NGV’s cash flow. But the exhibition is prominently sponsored by a gigantic international pet food (and chocolate bar) conglomerate—and the punters still have to cough up petty cashola? This seems a bit grim. The gallery is banking on our obsession with our pets, speculating that many of us are willing to pay for the quasi-narcissistic experience of seeing the distant relatives of our domesticated beasts represented in artworks spanning the centuries and the globe.

Jeff Koons, Puppy (Vase), 1998, white glazed porcelain, ed. 1394/3000 plus 50 APs, 44.5x 26.7x 44.5cm, National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne. Purchased, 2004 © Jeff Koons

They’re probably right. Cats & Dogs exemplifies the gallery’s populist, popular, and globally oriented approach to curation. The exhibition presents cats and dogs as archetypal creatures who appear across many art forms and cultures. Pets transmit a kind of epic transcultural myth: Everyone has them! Everyone has always had them! And you have one at home too! The value of this curatorial framework is that it is simple enough to make basic sense when bringing together very different works from the collection. Because it combines periods and genres and is presented thematically, instead of in any linear, chronological, or geographical order, it cannot be accused of the dreaded Euro-centrism. And it’s not like a populist pet show is a new idea, either; in 1981, partly in collaboration with the Melbourne Zoo, the NGV held an exhibition called Line and Feline, about cats in the collection (I only wish they had brought back the centrepiece of that show, Maria Kozic’s Nine Carnivorous Cats (1980), instead of showing Four Women (1985), a tragically kitsch Picasso ripoff featuring a small black cat by Roar Studios artist Mark Schaller). But the core issue with this framing is that it flattens specificity, sometimes creating jarring jumps between vastly different artistic contexts.

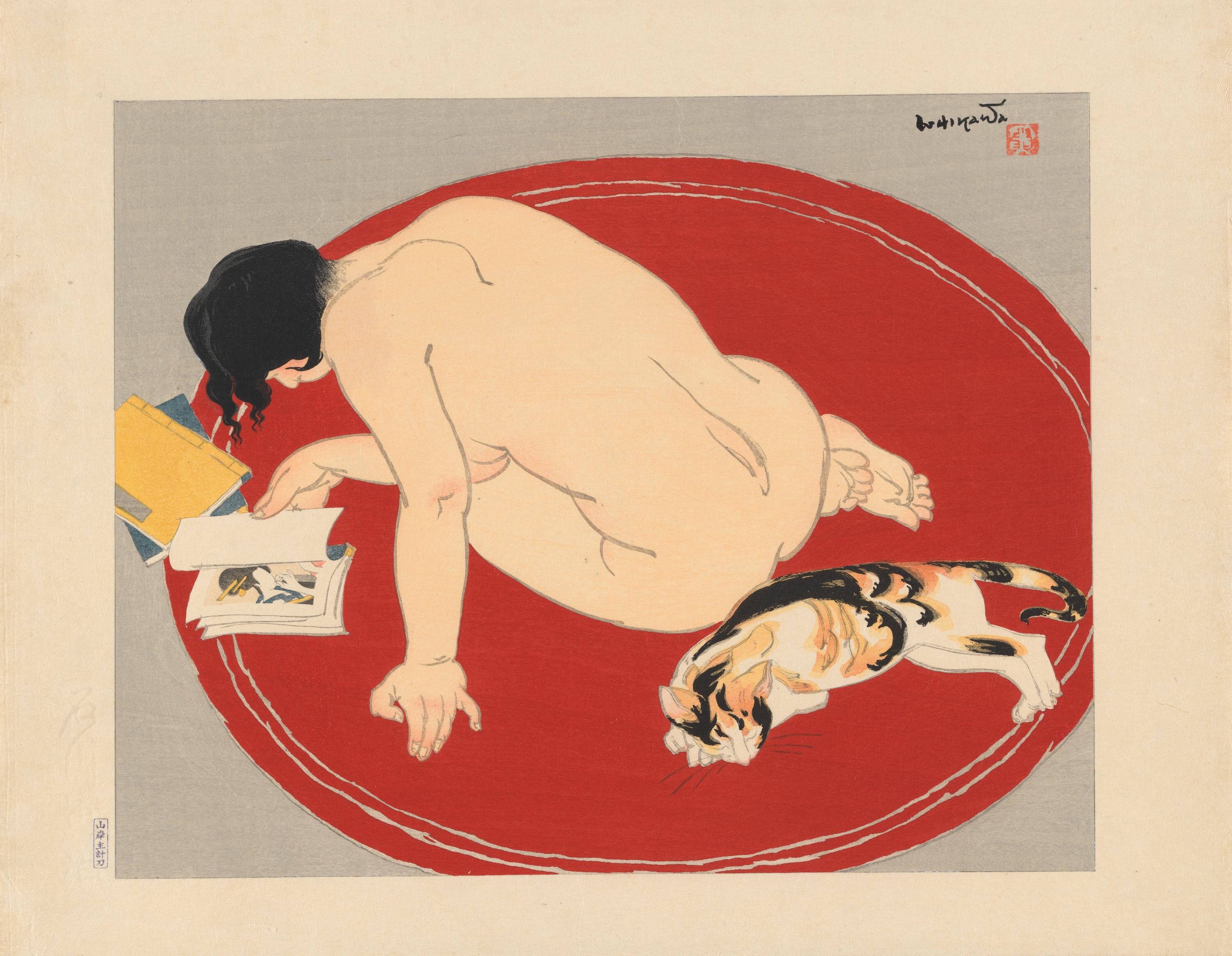

Ishikawa Toraji, Leisure Time (Tsurezure), 1934, colour woodblock, 48.0 × 37.0 cm, National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne. Purchased, NGV Asian Art Acquisition Fund, 2014. Photo: National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

Jan Steen, Interior, (c. 1661-1665), oil on wood panel, 55.6 × 43.0 cm, National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne. Felton Bequest, 1922. Photo: National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

Some artworks are displayed next to one another that are culturally and stylistically different in extremis. For example, under the thematic ‘Eroticat,’ Ishikawa Toraji’s Leisure Time (Tsurezure) (1934) sits adjacent to Jan Steen’s Interior (c. 1661-65). The former is a chic modern Japanese woodblock print of a nude woman lounging on a flat, red disc of carpet, reading a book in the company of a sleepy tabby. The latter is a Dutch genre painting set in a dank, dark room full of jovial, pink-faced beer-sloshers and one cat. In the centre of the painting, a woman’s fleshy tits are erupting from her dress, being suckled by a child on one side and groped by a cad in a feather hat on the other. Leisure Time presents pared-back feminine sensuality; Interior is all gouty Golden Age moralism. These artworks are both exemplars of their type—but are from parallel universes. The presence of cats and nudity in both is perhaps not reason enough to justify their proximity. This being said, it can be a relief to go from Versailles lap dogs to Alice Springs camp dogs.

Installation view of Cats & Dogs on display at The Ian Potter Centre: NGV Australia from 1 November 2024 to 20 July 2025. Photo: Tom Ross

In Cats & Dogs, the NGV is an institution both blessed and cursed by abundant riches. The omnivorousness of the curation, with its dredging of the depths of the collection, produces some delightful displays. But this approach can tip into a curatorial version of cute cat and dog videos, accompanied by feel-good pet ownership platitudes that could come from an ad designed to guilt us into buying more expensive pet food. There is little attempt to present sustained, substantive arguments about artists or their worlds, nor to “stay with the trouble” or engage with other influential new ideas about animal-human relations. That’s not the point here. The point is that the subject of Thomas Gainsborough’s portrait of an officer of the 4th Regiment of Foot, Richard St George Mansergh-St George, has a dog that looks just like yours. At home, stroking my cat as she lovingly headbutted my chin, one final critique materialised: there are simply way too many dogs in this exhibition.

*Thanks to Victoria Perin for sharing a clipping of Line and Feline.

Cameron Hurst is a contributing editor of Memo Review.