Beth Maslen: Maternal Figures

Amelia Winata

Here’s a theory: all backyard galleries eventually either die or professionalise. In Naarm, Meow (founded by Hana Earles, Calum Lockey, and Brenna Olver), and Guzzler (founded by David Homewood, Alex Vivian, and Luke Sands), lived hard and died young. Asbestos, which has slowly garnered a multi-generational following and therefore developed a remit outside of its art-school peers, will close this year when its hosts Britt d’Argaville, Aden Miller, and Josh Krum are evicted from their Brunswick East share house. These galleries belong to the art world equivalent of the 27 Club—forever immortalised in death. May their souls rest in peace.

Then, some choose the professionalisation route. Animal House Fine Arts—located in a first-floor Brunswick East disused lawyer’s office—is one such example, albeit in a roundabout way. Opened in 2023 by Matthew Ware, Animal House is somewhat of a successor to the backyard gallery Savage Garden, which Ware founded with fellow artist Jordan Halsall. Ware also cut his teeth at Geoff Newton’s Neon Parc. Animal House is like the baby version of Neon Parc and the grown-up version of Savage Garden (keeping it in the family so to speak). Ware hosts VIP cocktails, stages artist talks, and takes out ads in Art Collector magazine. Of course, the gallery still has the recent-graduate charm of its predecessor. A friend’s little sister makes the cocktails; the talks are conducted on extreme hangovers, and the ad’s photograph is of a dog Ware recently looked after.

Out the back of the Animal House gallery is a collection of studios out of which Tommaso Nervegna-Reed, Bronte Stolz, Ben Bannan, and others work. Downstairs is Versa, a skincare and anti-wrinkle clinic frequented by many artworld girlies (including yours truly). It is increasingly servicing members of Ware’s key late-twenties/early-thirties audience—a tell-tale sign that the trappings of aging eventually catch up with us all.

Beth Maslen’s current exhibition at Animal House, Maternal Figures, somehow picks up on the feeling of mortality that begins to set in in our mid-twenties—and that we’re only relieved of when we die. As the exhibition title hints, mothering is a central theme of her show—undoubtedly a hot topic. Last week, Tara McDowell wrote a review of Laure Prouvost’s exhibition Oui Move in You at ACCA. The show sees Prouvost paying homage to her matrilineal line. Maslen’s show is also about matrilineage, but I feel it is just as much about what parenting symbolises in relation to time and one’s sense of mortality. Comprised of sculpture and photography, Maternal Figures memorialises and gives a visual language to the continually shifting sense of self developed vis à vis figures of authority and origin.

To me, an affect of disengagement, or loneliness, is Maternal Figure’s primary sensibility. Upon walking into the gallery, the viewer encounters a sculpture, Maternal Figures 12 (2023/24), that represents a larger-than-life swan. A base made from Victorian ash and plaster has been overlaid with two large curls of oak veneer representing the bird’s wings. The swan, a classic signifier of maternal care that shields its young beneath its large wings, is the show’s obvious nod to motherhood. However, the bird is abstracted, giving the work a sense of detachment and coolness. In reality, it is just a white rectilinear frame, devoid of a face or other life-giving characteristics, while the very measured curled oak veneer wings are the sculpture’s only flourish—and even then, describing them as a flourish feels like overstepping.

The rest of the works in the exhibition, a collection of photographic prints, contribute to this feeling of disengagement. Inanimate paired or grouped objects suggest a parent-child relationship, but don’t elicit warm fuzzy feelings. Like B-sides, most items have been shot from off-hand angles and are not entirely in frame. They remind the viewer of the extra photos film cameras take to use up a roll. Or, to update that reference, an image accidentally taken by a phone camera that has been accidentally left on. For example, Maternal Figures 4 (2024) depicts a multi-armed chandelier hanging from a ceiling, which sits in the dark and has been shot with an unflattering flash. The image is out of focus. The angle from which the chandelier has been photographed—from below and off-centre so that part of it is cut off—also adds to a sense of detachedness. Switched off as it is (despite its many bulbs), the chandelier is beautiful but ultimately a lonely, useless object, only having been unintentionally perceived in retrospect.

Maslen’s photographs could be described as the meek love child of Wolfgang Tillmans and Thomas Struth. This union of a fly-on-the-wall sensibility with a technological bent causes the viewer to pause and question whether the photos have been digitally manipulated. In fact, none have been, all have been shot on film and either developed in the darkroom or digitally printed. Always eager to know what is cool, I regularly ask student artists to give me the 411. Recently, in response to my query, a young Melbourne sculptor informed me that minimalism is on its way out and that sincerity is on the up (holes, incidentally, are also apparently in). Maslen’s work is very sincere.

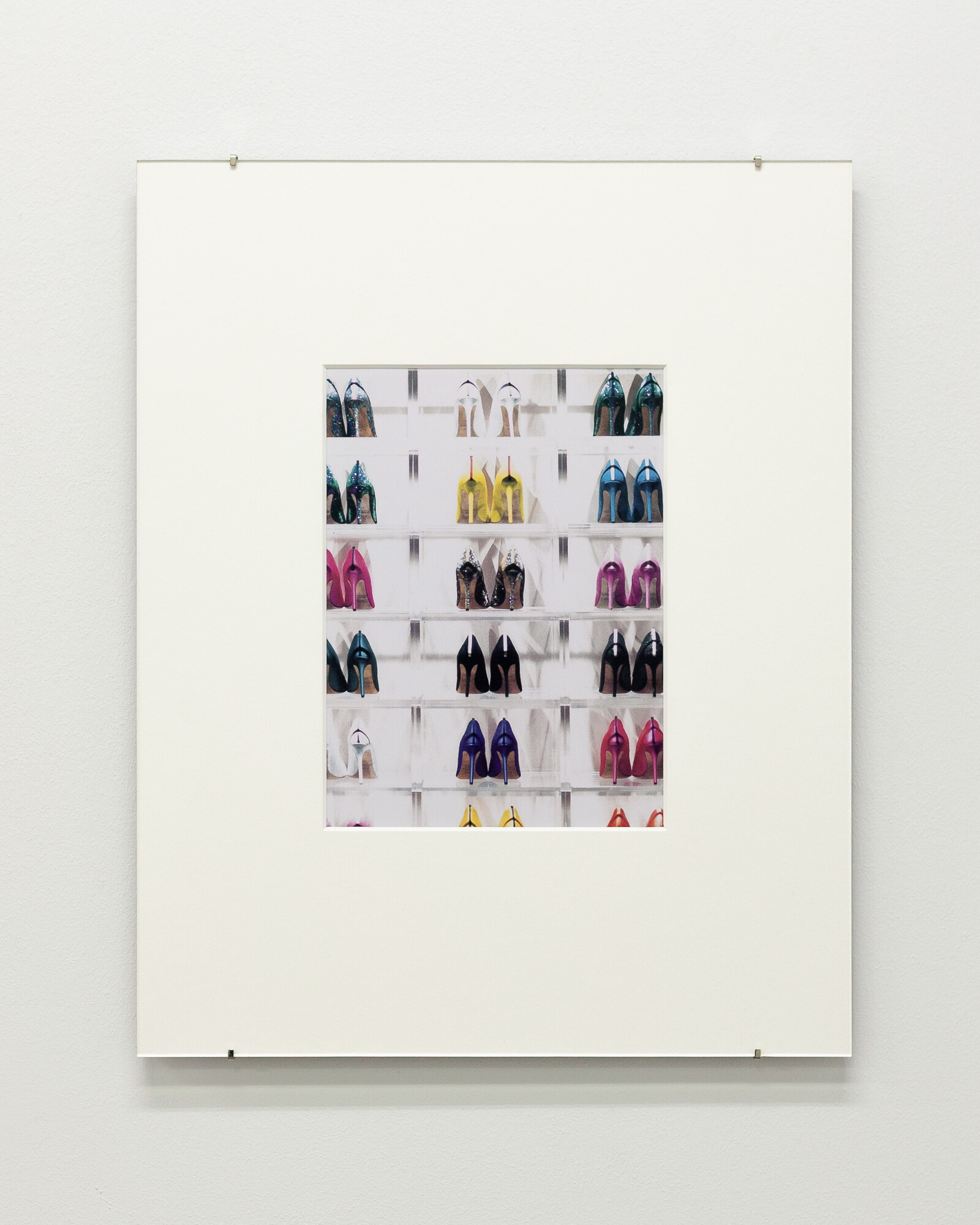

The exhibition has brighter and more sharply focused images, such as Maternal Figures 10 (2024), which depicts rows of colourful stilettos lined up in a cupboard, or a larger image of cars in a workshop (Maternal Figures 11 2024). But even these stop short of the overly theatrical effect of Andreas Gurksy’s or Jeff Wall’s photographs. Instead, these images opt for a strange display of luxury that feels oddly memorialising. The stilettos are lined up like taxonomies; the cars include what appears to be a vintage Volvo reserved for Sunday spins. Could this be the luxury of comfortable living that we vicariously experienced through those of our parents’ generation and will always struggle to reach in our adulthoods? The exhibition text hints at missing something never experienced and unrecoverable. As Maslen writes, “I wail all day for the shooting stars I miss.” In any case, the compulsion to memorialise is not dissimilar to how Düsseldorf Schule mummy and daddy Bernd and Hilla Becher created their typologies of pre-war German industry—gas tanks, blast furnaces, coal bunkers—in a refusal of the natural passage of time. We desire to freeze things even as they evaporate before our eyes.

The melancholy continues. A recurring image is an unfired clay swan that has been developed in black and white in the darkroom. Each photograph is negligibly different, with the exposure being the most obvious change from one image to another. The swan is ghostly, manifesting as a grainy splotch that is always on the brink of disappearing but never actually doing so, and continuing to appear again and again. To invoke just one cliché, these images remind the viewer of a flame that refuses to extinguish fully. Something so pitiful but painfully touching about the swans—often hung in pairs, very abstractly signifying a mother and child—tugs at the heartstrings.

However, I must battle against the compulsion to paint Maternal Figures as merely encompassing direct domestic (biological) mother-child associations. Indeed, there is something to be said about the legacy of senior practitioners who have shaped younger artists’ practices, usually through teaching. Maslen’s work recalls one Naarm art mum, Lou Hubbard, whose work is similarly anthropomorphic. Indeed, the influence of photographer Ruth Höflich, who taught Maslen at Monash, is undeniable. Höflich’s whimsical photographic sensibility—and penchant for presenting small photographs with an oversized matt board pressed between two pieces of glass—are stamped all over this exhibition. Maslen is currently enrolled in an MFA at Bard, where Höflich also studied, and she also recently appeared in Höflich’s film The Flood (2024). My point is that the idea of “mothering” in Maternal Figures is purposely loose and abstract to encompass larger themes such as transference and the aging that necessarily happens as one learns.

Despite its commercial gallery profile, Animal House is still a start-up in a musty lawyer’s office. One enters the space via a low-ceilinged carpeted hallway, and the gallery is doing its best to mimic a white cube, but it’s just a smallish disused office. On the day I visit, Ware is attempting to fit a found window into a hole in his office’s wall that he has been covering with a poster. Despite this left-of-centre commercial model, I could have done without Maternal Figures’s offbeat hang. In addition to the main gallery where the swan sculpture and a handful of photographs were installed, more photographs have been hung in the hallway that runs down the side of the building. This approach gives each work more space but makes me feel like I’m in a faculty hallway at Melbourne University that has been jeujed up with collection works. And it is preferable to be able to view a work from both afar and up close. However, I don’t begrudge this attempt to engage with Animal House’s obvious in-betweenness. Because in-between is precisely what it is. It is no longer in its infancy, but still on its way to being fully fledged.

And yet, being fully-fledged is challenging because it is like a full stop. How is it that there is an immediate sense of doom as soon as one begins to develop beyond childhood? Maternal Figures is acutely aware that the child-parent binary is also a marker of time and a moment for intense introspection. What happens, for example, when we are the age that our parents were when we were born, or the age our heroes were when they produced their masterpieces? Babies can’t be mummies. Whether we want to or not, aging is inevitable. To which melancholia and memorialisation become ersatz mechanisms through which to circumvent mortality.

Amelia Winata is a contributing editor at Memo. She recently completed a PhD in art history at the University of Melbourne and is Curator in Residence at Gertrude Contemporary.