Gian Manik, You own the school, embrace your responsibility for its legacy, presented at Gertrude Glasshouse, 2024. Courtesy of the artist and Sutton Gallery, Naarm Melbourne. Photo: Christian Capurro

You own the school, embrace your responsibility for its legacy

Hilary Thurlow

It feels too easy to begin a review of a painting with a comment on either the perpetual death of painting or its endless revival. So, I won’t. You don’t have to look much further than the recent Netflix series Ripley (2024), the history drama Caravaggio’s Shadow (2022) or even Derek Jarman’s film Caravaggio (1986) to understand Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio’s (1571–1610) unceasing hold on us all, even though he died 414 years ago. While Caravaggio’s paintings are a dime a dozen in the Northern Hemisphere, there’s not a single painting attributed to Caravaggio in Australia.

Twenty years ago, the Old Master’s work toured the East Coast, hopping between the Art Gallery of New South Wales and the National Gallery of Victoria in a ticketed touring exhibition titled Darkness & Light: Caravaggio & his World that “featured key paintings (that) demonstrated the scope and quality of Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio’s (1571–1610) revolutionary vision.” There were nine attributed paintings—the Protection of Cultural Objects on Loan Scheme was put to work—and over fifty works by the Master’s devout followers.

Now, painter Gian Manik has returned Caravaggio to Naarm. Instead of lining a hallowed halls of the NGV, the Old Master’s work finds its place hanging in Gertrude Glasshouse in a show titled You own the school, embrace your responsibility for its legacy. The painting appears to be floating, suspended from the ceiling with wire, and centred in the space is a single stretched painting. Manik’s Untitled (2024) is a reworking-cum-copy of the second iteration of Caravaggio’s Supper at Emmaus (1606).

Gian Manik, You own the school, embrace your responsibility for its legacy, presented at Gertrude Glasshouse, 2024. Courtesy of the artist and Sutton Gallery, Naarm Melbourne. Photo: Christian Capurro

The first version of Caravaggio’s Supper at Emmaus, housed in the National Gallery, London, dates back to 1601, predating the second version by five years. More saturated in palette and theatrical in composition, the 1601 version is more liberal. Notably, Christ in this earlier rendition lacks his trademark beard and looks a bit like a twink—Caravaggio never painted a female nude—while the later version portrays more subdued figures confined to their canvas. The biblical story behind the painting revolves around Jesus post-resurrection; he went incognito, only revealing himself to two of his twelve disciples, Luke and Cleopas, at a local inn located in the town of Emmaus (what we now know as the West Bank). These two paintings supposedly capture the exact moment of Christ’s reveal, inviting his disciples to break bread and share the word of his resurrection.

Reproduced from memory (allegedly) and arguably a better example of chiaroscuro, Caravaggio’s second Supper at Emmaus, was painted in 1606, This rendition depicts a wearied Christ and introduces a new character, the innkeeper’s wife, to the scene. By 1624, the painting found its place in the collection of Marchese Patrizi, allegedly commissioned by this noble Roman patron, or so Wikipedia tells me. Currently housed in the Pinacoteca di Brera in Milan, Supper at Emmaus shares its home with one of Caravaggio’s most contested paintings—the long-lost second version of Judith Beheading Holofernes, which was discovered in a French attic. Despite being on public display, questions linger regarding the authenticity of this painting.

Gian Manik, You own the school, embrace your responsibility for its legacy, presented at Gertrude Glasshouse, 2024. Courtesy of the artist and Sutton Gallery, Naarm Melbourne. Photo: Christian Capurro

We could liken Caravaggio and his contemporaries to modern-day tradespeople or fabricators, tasked with replicating or amending works they had done before, based on commission briefs. I imagine conversations would’ve gone something like, “I enjoyed that fresco you did a few years back … Could you do something similar? But on canvas? And can you use my wife’s face as Magdalene?” Perhaps the patron would’ve asked for some touches of lapis blue to be painted on the surface too, denoting their wealth and status. But these commissioning briefs are not a distant memory of the past and still happen today, every day. Ask any assistant at a commercial gallery and they’ll be able to recount uncanny enquiries for commissions—like replicating a painting but smaller in size or in a slightly different version but in an alternate colourway. Ironically, Glasshouse is one of Naarm’s only spaces to be patron-ed by Michael Schwarz and David Clouston.

Back to the new painting. Manik’s quasi-forgery initially appears as if it is the “true” Caravaggio. Having never spied Supper at Emmaus in the flesh, Manik relied on a high-res image found on the internet—copied the image of the 1606 painting, readily available for anyone willing and wanting to view the Caravaggio. The painting’s varnish shows signs of cracking, and the linen on its verso shows weathering and aging, with a small patch on the lower-right-hand side, signalling some kind of conservation or overpainting efforts. Furthermore, the measurements of Manik’s Untitled (141 × 196 cm) match those of Supper at Emmaus (1601), and the composition faithfully mirrors that of the original.

But this painting is not a flawless reproduction. While internet-sourced images tend to conceal surface textures, appearing perfectly flat and rendered, Manik has taken small liberties to reinstate the aura of the nearly replicated masterpiece. Because the artwork is not an exact copy, it still carries the uniqueness of an original, able to be experienced in a distinct time (now) and space (Gertrude Glasshouse). The painting is not an appropriation but a simulacrum—a copy of a copy of a copy—and serves as a test of re-presentation, akin to a duck-rabbit situation. It looks, smells, and feels like a Caravaggio, as if it were painted in the seventeenth century. It also stands as an anachronic gesture, made well outside of its time and historical context. Enough care has been taken as to ensure the painting looks the way an old painting should look, but with not so much care as to prevent small temporal slippages: synthetic pigments in the oil paint, nails made by machines, and so on.

Gian Manik, You own the school, embrace your responsibility for its legacy, presented at Gertrude Glasshouse, 2024. Courtesy of the artist and Sutton Gallery, Naarm Melbourne. Photo: Christian Capurro

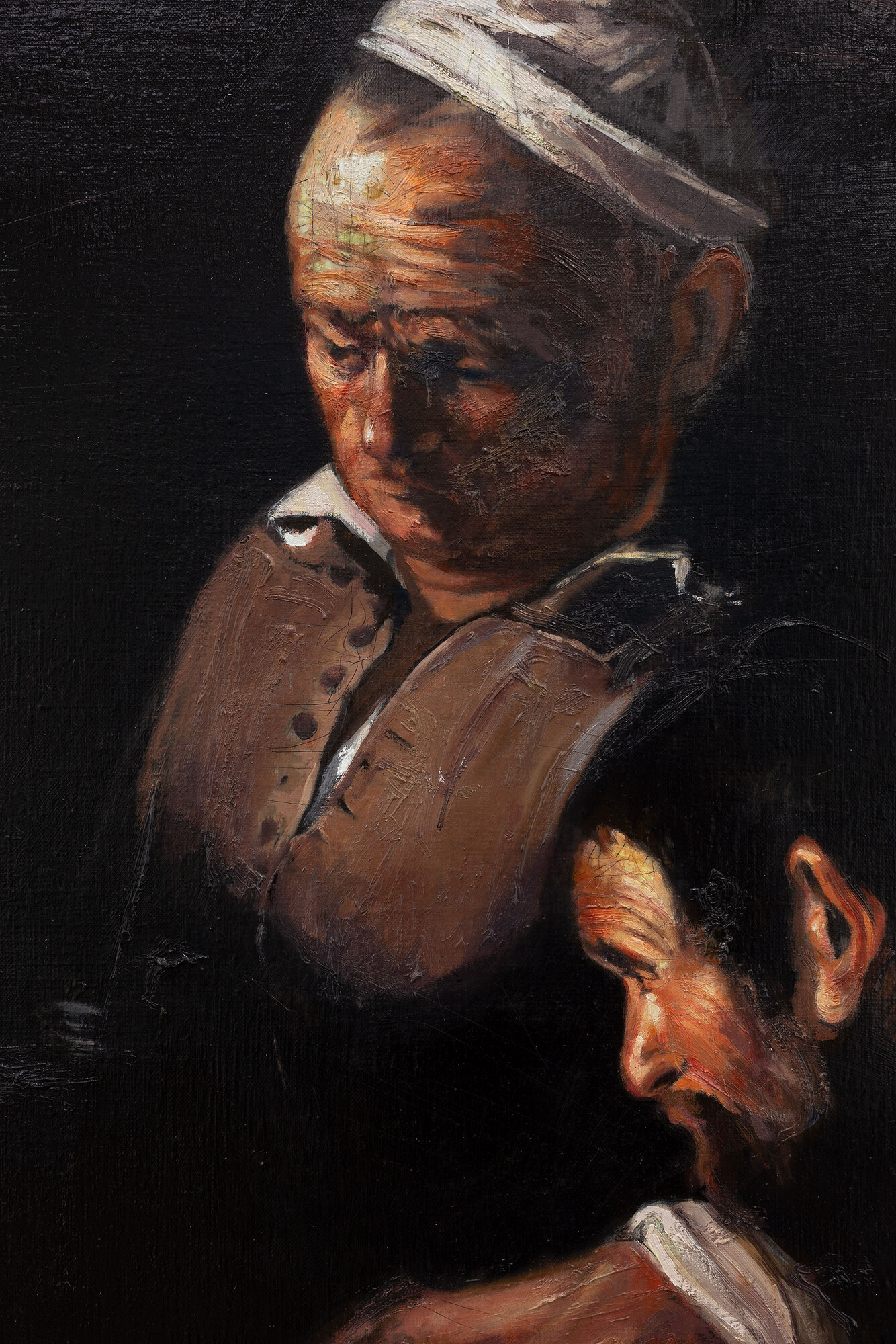

Where Caravaggio has carved the innkeeper’s wife’s furrowed brow with intricate creases, Manik’s interpretation is more painterly and less astute. The hollowed area under her eyes appears more El Greco and mannerist rather than an example of Caravaggio’s realism. Attention is drawn to the buttons adorning the innkeeper’s vest too. Whereas Caravaggio’s buttons are meticulously placed and neat with not one out of place, Manik’s portrayal shows a dishevelled innkeeper with missing buttons and worn wrinkled fabric.

Gian Manik, You own the school, embrace your responsibility for its legacy, presented at Gertrude Glasshouse, 2024. Courtesy of the artist and Sutton Gallery, Naarm Melbourne. Photo: Christian Capurro

Untitled isn’t Manik’s first attempt to copy (replicate?) an Old Master. Throughout his childhood, he would pick images of works by Old Masters, painstakingly painting and sketching them to a point where he felt they were good enough to pass as a copy. In his youth, Manik further honed his skill by copying (or re-presenting) courtroom scenes in Perth as a courtroom sketch artist for various media outlets. His grandfather dabbled with reproductions too, copying Rembrandts over and over. So enamoured was he with the Dutch Master that Manik’s mother was named after Rembrandt’s wife, Saskia. The desire to copy those who have come before feels like a universal rite of passage for painters everywhere. Even Bidjara, Ghungalu and Garingbal artist, D Harding perfectly replicated Australia’s own Master Brett Whiteley while in high school, eventually abandoning the practice after learning of Whiteley’s unsavoury hobbies.

The act of creating painted copies reads as almost amateurish at first glance, as if the original painter holds the elusive claim to genius. However, there are instances where this replication serves as a conceptual endeavour, aiming to resurrect some kind of historical moment, as exemplified by Ian Burn recreating Mondrian’s lozenges. Copyright and legalities are of no qualm either. Manik’s working falls under fair use; any claim of Caravaggio’s copyright expired 334 years ago.

Forgery comes into play here too, although Untitled is neither quite a forgery nor a counterfeit. Living in a time where the cost of merely living exerts significant control over our lives and practices, forgeries are too expensive to produce. They’re also a time drain. Constructing a believable forgery, in this particular case, would entail acquiring a work from seventeenth-century Italy, ideally Roman, and carefully sanding back the painting’s façade to reveal any underpainting or canvas. Depending on the pigments used, one might need to whisk together your egg tempera or even DIY your oil paints to be chemically comparable to those used by the Old Masters. After all of that, you’d need to have a convincing back story—one that will persuade auction houses, experts, and collectors alike of the work’s authenticity and provenance.

Gian Manik, You own the school, embrace your responsibility for its legacy, presented at Gertrude Glasshouse, 2024. Courtesy of the artist and Sutton Gallery, Naarm Melbourne. Photo: Christian Capurro

Ultimately it doesn’t matter if the work is real or a flawless reproduction or not. It’s good enough to read as a Caravaggio; the re-presentation, and the aura are all there. If anything, it’s more interesting that the work isn’t every inch the Caravaggio. Sure, the work is a technical flex in a world full of technically impeded painters, but importantly there’s something utterly democratic about Manik’s play. By installing a “Caravaggio” in a place where there are none, and where on the odd occasion they’ve travelled to our shores but come with a hefty price tag to see—twenty-two dollars in 2004 or about thirty-six dollars in 2024. It’s improbable that the 1601 nor 1606 iterations of Supper of Emmaus will likely to ever travel to Australian shores, but we will always have Manik’s Untitled.

Hilary Thurlow is a PhD Candidate in Art History & Theory at Monash University. Her research centres on the work of Cuban artist, Tania Bruguera.