Photo: Andrew Curtis

Sonny

Giles Fielke

“What a perfect encapsulation of everything wrong with the Australian art world’s response to an unfolding settler-colonial gen0cide.” Thus Mitch Cumming, artist, poet, and founding co-director of KNULP, Sydney. His comment—with 221 likes when I see it—is posted below Tolarno Galleries’ third and final exhibition announcement for “Sonny” on Instagram from 18 February (programmed to end today, it has now been extended through 20 April). In the video the exhibiting artist, Ben Quilty, is seen painting the name of its title onto the wall of Gallery 2. “One painting of Sonny for every little child killed in the October 7 attack by Hamas,” Quilty is quoted saying in the exhibition’s email announcement, which was then qualified in Kerrie O’Brien’s article for The Age on 15 February: “I made one work for every (Israeli) child who was killed or kidnapped (on October 7).” (At some point Tolarno decided to hide the existing comments on the post and disabled any new ones from being added to the maelstrom, probably for the best.) Sonny is a three-year-old child whose parents are friends of the artist. Somewhat inexplicably, Nick Drake’s narcoleptic banger “Pink Moon”—the title song of the LP first released in 1972—has been chosen to accompany the video. Is this some kind of elaborate dog-whistle? To whom, I wonder?

Let’s begin with Drake. A neo-romantic figure of the 1960s British folk-revival, Drake was a Cambridge University student and acoustic strummer depressive, who subsequently overdosed on anti-depressant medication and died aged twenty-six in 1974. Listening to Pink Moon fifty years after its release, I imagine Drake’s third and final record as his lament for the period Winston Churchill spent painting on the French Riviera another fifty years earlier. Thankfully, Churchill is not explicitly referenced in the present show, but I remember that he took up painting after travelling to Gaza as the British Secretary of State for the Colonies in 1921 (and after he’d been voted out of office for the first time). Further adding to the melange are five framed drawings by Syrian children also present in the gallery. Apparently taken from Quilty’s edited book for Penguin, entitled Home: Drawings by Syrian Children (2018), this directs me to the foreword by Richard Flanagan as there is a copy of the book lying on the gallery’s seating. None of the works are for sale, and I am assured by the director that they are a small part of a much bigger body of work. Maybe these will be portraits for the thousands of children killed since October 7 (whom Quilty refers to in far vaguer terms: “Now more than 10,000 children are dead in Gaza…”). Six months after the Hamas attacks, more Gazan children have been killed by Israel than the total number of people living there when Churchill began planting trees in 1921.

With previously unexamined, incandescent rage I have always hated the cynical, pathetic paintings pumped out by Quilty for the past two decades. That this “bleeding heart,” “lefty,” “private-school boy” art is so perfectly placed at the exact centre of the mediocre means that it sells (when it is for sale, and it usually is) like proverbial hotcakes. It is the present apotheosis of Australian cultural mundanity applied to canvas. Quilty is himself the sanitised inheritor of the mantle once claimed by Adam Cullen, Australia’s best living painter (deeply ironically), at the point of his untimely death in 2012, the year after Quilty won the Archibald Prize for his portrait of the artist Margaret Olley (who also promptly passed). Like Cullen, Quilty courts controversy as an artistic strategy, further inspiring younger painters like Benjamin Aitken to continue ploughing the same tired field at Huckleberry Farm. Don’t get me wrong: there is no doubt these artists are, or were, talented virtuosos whose handling of the brush and colour is maverick, yet winning the Archibald Prize is the constrained summit of their enterprise (so far Aitken has been a five-time finalist). The narcissism of small differences is perhaps the shortest way to explain my personal loathing. I see myself in Quilty’s public persona: lefty, privately-schooled, etc. “Absolutely hopeless” is how I’d described Quilty’s work at the inaugural Triennial at the NGV—a thickly impasto’d life-jacket titled Vest (2017). It’s the word—hopeless—the artist would later use to describe himself in a typically self-deprecating interview, mirroring my assessment. In December of 2018 he had presented, in collaboration with artist Mirra Whale, a Christmas tree sculpture for St Paul’s Cathedral in Naarm Melbourne made out of life-jackets discarded by refugees. He was then photographed wearing a crown of thorns for Good Weekend in 2019. Jesus Christ.

Straight white male, self portrait (tongue) (2014) is the oil on linen work that perhaps best encapsulates the internal motor for Quilty’s practice, slurping up everything in his path. Guilty as charged. For Quilty, art is “a way of coming to terms with who you are and why you are here.” To read between the lines, this might mean something like: by what dumb luck did I end up here and how do I carry this burden of privilege? Being heavy in the head is hardly a compelling basis for an artistic practice, certainly not a definition of art that many subscribe to, but alas. Alack. The industrialisation of guilt buttresses a not insignificant part of our economy, based, as it is, on asset management. This might be the best way to explain Quilty’s position in contemporary Australian art: “blue chip.” This is our problem, not his, however. Quilty is not the target, or rather, if he is, that is his cross to bear. Let me explain why below.

Hopelessness is a feeling, certainly. No-one in their right mind is celebrating the industrialised slaughter in Palestine. But as Masha Gessen recently pointed out in their column on the self-immolation of the United States Air Force serviceman Aaron Bushnell (whilst faithfully citing Judith Butler), there is an important distinction to be made between nonviolent acts of despair and politics. While the moralism of Quilty’s work draws heavily on Catholic tropes of sin and forgiveness, it is certainly the case that he eschews politics. This is, I believe, the crux of my issue with Quilty’s work: for too long only the economic has been emphasised, with its counterpart, politics, apparently understandable only through the logic of the market. This means despair is assigned a positive value. This is not Quilty’s fault, of course: it is a social condition that is pervasive, especially so it seems here in Australia. Our political economy is symbolised by drunken stupidity (personified by Barnaby Joyce); larrikins are not radical insurrectionists—especially amongst young men, anything that is not funny is terrorism. The fact that Quilty is celebrated for acting for the former makes my point. The best painter is a useful idiot.

In the editors’ introduction to David Homewood and Paris Lettau’s recently published collection of texts on the medium, Ends of Painting (2023), they chose to include the reasons given by someone they call a “prominent British art historian” to decline to write about painting today: “Painting is unfortunately too caught up now in the rituals and rites of finance capital,” the British art historian replied, “and therefore a major prop of the sclerotic social relations of the dominant art world.” It is certainly a frank, and potentially misguided, assessment of the medium, but it nevertheless provides an effective reason for why contemporary painting must continue to be examined. If it is a prop, why does it not appear as such? Modernist discourses have supposedly prepared us, as Frank Stella put it, to “see what we see” (hence the pervasiveness of mirrors). Yet Madeleine Kelly’s curated group show, “At Home With Painting,” currently on display at SCA Gallery in Gadigal Nura Sydney, is premised on painting being otherwise. The follow up question is: has painting as a medium—the act of pushing pigment around on a surface, which is how Quilty himself has described the pleasure of his métier—become like the life-jacket for this so-called “dominant art world”? Painting is a medium, but before that—as Harold Rosenberg noted as early as 1952—painting is an event. The event is a political formation, the medium is its formalisation. Today the event of painting seems to have been short-circuited, it feels foreclosed. (Coincidentally, one of the better painters practising today, Tim Bučković, is currently exhibiting his new works, including one titled an event, at 1301SW.)

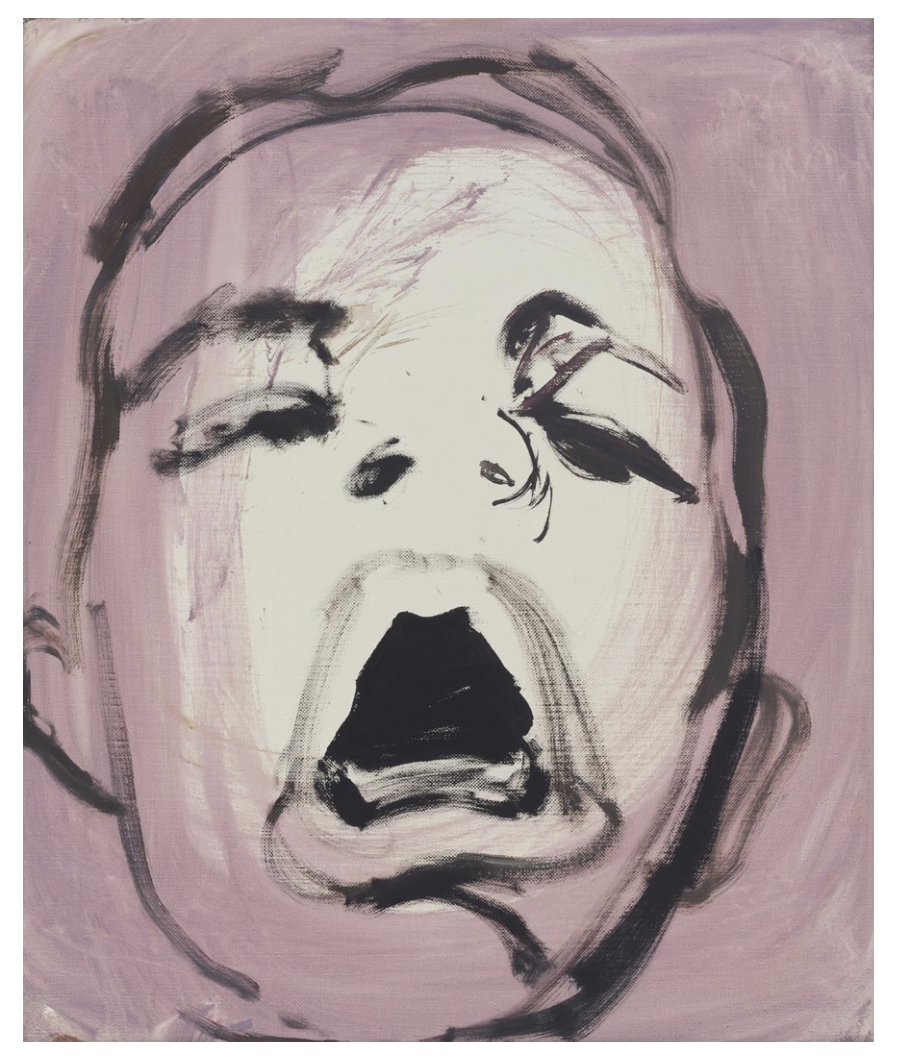

If you are still reading, now is the time to look at the thirty paintings on display—put aside the abstract equation matching the series to the number of Hamas’s victims, which is murky at best. Eyes closed, mouth opened in a cry, the image is universal in the sense that it is the thing everyone does as a child. To seek out the broadest audiences, Quilty chooses popular images, famous people, cars… this appeal is his target. Formally, most obvious feature is the orifice of Sonny’s mouth. It is captured as a kind of bell-shaped abyss at the centre of the unframed canvasses, all measuring 61 × 51 cm. It is a visual metaphor of the impossibility of enunciating pain. Arranged in six groups of five across two walls and in two rows in the gallery, reading left to right, the top row is first and then the bottom rows overlap with the final two portraits in the previous group above. The last painting bottom row overlaps with the first portrait in the next top row grouping, and so on. Sonny is in pain, lunging for the comfort of a loving embrace (instead the child has had their photo taken). Sonny is also a formula, known only to the artist. The treatment of the paint is fast and direct (impressionist, sure, aiming for Manet). The most affecting portrait is the last: on a purple ground and with black lines. It recalls Warhol’s images of Mao (also fifty years old). In this way, the last is also the first image, the rest become experiments—something Olley had told him explicitly to stop doing in 2011.

Photo: Andrew Curtis

Sonny’s basis in photography, and the inclusion of curated elements like the drawings by traumatised children, can be explained by Quilty taking inspiration from the work of photojournalism, for example, from his cousin Andrew Quilty. In his report from Kunduz, Afghanistan, in 2015, his Walkley-award winning photograph records the scene at the Médicine Sans Frontières hospital there, which he had arrived to photograph one week after it had been bombed by a U.S. AC-130 gunship, killing at least thirty staff and patients at the hospital in the city recently retaken by the Taliban after fifteen years under the control of Northern Alliance and U.S. special operations forces. In the photo a headless man lies prone on an operating table, inside the shelled remains of a hospital theatre. A week of dust and necrotic, stale air has settled upon the scene. It is damning evidence of what the U.S military investigators would later describe as an “accident.” Today it is recognisable in scenes from al-Shifa hospital in Gaza, pounded by Israeli soldiers with weapons provided by its allies, including the US and Australia. There is no politics here, just death. (Painter Quilty was Australia’s chosen war artist in 2012, and the theatre of war has remained the Middle East.)

Just a few days ago, Leonard Joel auctioned a freshly minted Quilty oil on linen painting titled The Daughter (and which was first exhibited at Tolarno Galleries in June 2023). Passed in on the night, I had initially assumed it was some kind of tax-deductible purchase for the nine-months it has been privately owned. Blue chip stock permits this kind of accounting. There is also an alternative: is it possible that Sonny, Quilty’s recent intervention into the images of Israel’s attempt to eradicate Palestine—despite his principal sympathies lying with Israeli victims, and the inclusion of images by children—has drawn the ire of collectors who have been conducting a pressure campaign behind-the-scenes, targeting prominent artists who speak out on the topic of Palestine? The performative expulsion of Mike Parr from Anna Schwartz’s gallery late last year is only a symptom of this broader shift in Australia’s commercial art world. The apparent lesson is: keep politics out; this is business only. And yet Quilty is only too happy to oblige (hence why none of the present works are for sale).

What I mean to say is that this problem is not Quilty’s: it is structural. The frustrations acted out by commentators like Cumming (and myself) is borne of the knowledge that the popular discourse on art in Australia remains in a state of arrested development. In his boyishness, and his appeal to his supporters (usually older women, starting with Olley but extending to figures like the current director of the National Gallery of Australia, Nick Mitzevich), that places Quilty like a deer in the headlights of a Holden Torana. The act of painting as a tired cliché of the cultural cringe that provides the substance and backbone to the art institutions means that Quilty has found himself trapped as the poster boy caricature of the masculine death drive.

Profiled in The Guardian by Germaine Greer (2009), and then by Brigid Delaney (2019), precisely all that is required to conjure up this constellation is here. The former includes the revealing line: “In the outback, the phenomenon of white-boy self-destruction intersects with Aboriginal recklessness, suicide and parasuicide.” It’s about as novel and repulsive as a southern cross tattoo. Eugene Yiu Nam Cheung (whose article “The Canonisation of Ben Quilty” was published by the now-defunct, ironically named, Running Dog online arts journal in 2019) seems to be in broad agreement with Delaney. The question has already been asked: why do we need a bloke-like painter to lionise today? Why Quilty? But “who needs him?” is the right question to ask. And the answer is important. A particular status quo is revealed in the contours of his slap-happy application of colour—it is one that is also threatened and scared, constantly, especially now. The joke isn’t funny anymore.

Photo: Andrew Curtis

So, instead of (as well as?) spending your time today venturing into the city to stare into these syrupy, smug, and sad paintings, why not go and see Sofie McClure’s new multiscreen audio-visual installation Forward, Backward at Quality, upstairs at 1B Marine Parade, Abbotsford, while it’s on, today or tomorrow (and now next Monday to Wednesday in the evenings between 5–7 pm). Seek out the NO PHOTO 2024 campaign—a series of publicly posted black squares on white A0 paper, with credits to the Palestinian photojournalist Motaz Azaiza and accompanying text descriptions of the concealed, unspeakable images from Gaza. This apparently spontaneous campaign targets the saturation of the PHOTO 2024 festival. That is, the status quo and its “respectful impartiality” (a particularly vapid formulation, which Sophia Cai had tried to point out before her essay was spiked).

Meanwhile, Quilty remains a portraitist, perhaps even a caricature artist, of himself. This focus explains his career. “I thought to make a painting of my little friend Sonny, from a photo I’d taken of him after he’d banged his lip on the edge of a table.” It is the simplicity of ideas for portraits such as this that have permitted Quilty to continue to paint the same image over and over, ad nauseam. The quote is dated 8 November 2023 and was included in the first notice of the show that Tolarno posted online at the beginning of February this year. In the image that accompanies the announcement, which includes the handle of the NGV and Penguin books, among others (as well as genuinely strange hashtags like #littlefriend, #bangedlip, #richardflanagan, and #drawingsbysyrianchildren), Quilty is staring back at the camera from his studio. Works from the Sonny series are visible on the walls behind him (the post has by far the most likes on Tolarno’s Instagram). His cold confidence exudes through the image, daring you to love or hate the work. Yet there is nothing to hate about it, except for the cynicism of the entire exercise. This isn’t Quilty’s cynicism, however. It’s ours, and we can’t look away.

Giles Fielke is an editor of Memo Review.