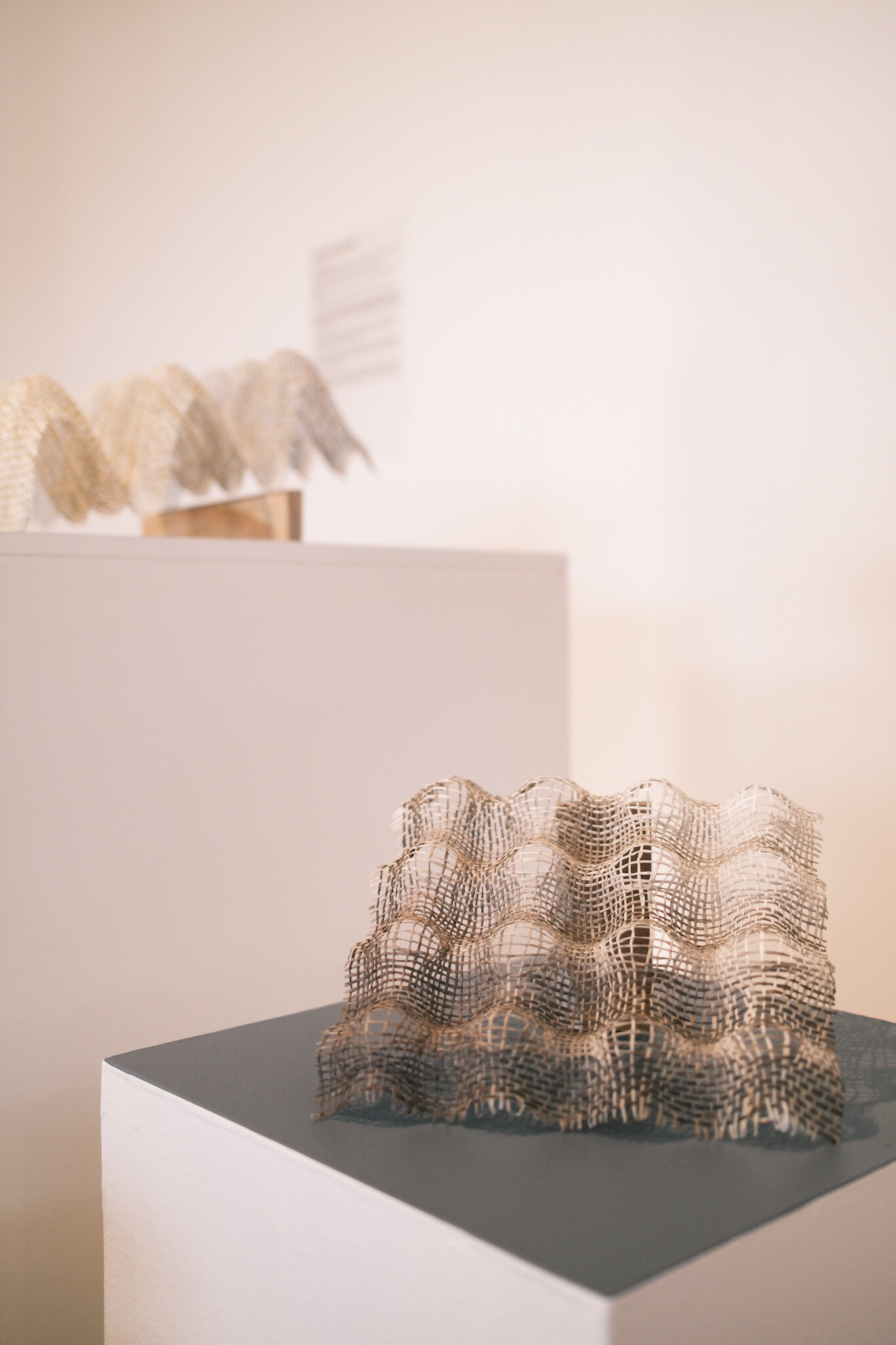

Slow Colour, installation at Australian Tapestry Workshop, 2025. Photo: Tom Hvala

Slow Colour

Anna Parlane

The title of the Australian Tapestry Workshop (ATW)’s current exhibition, Slow Colour, is a little ambiguous. On one hand, it could be understood simply as a description of the relaxed pace at which the exhibiting artists produced the hues in their work. Curated by the ATW’s Adriane Hayward and Beck Jobson, the show brings together five local and two international artists—all women—who work with natural dyeing techniques or found pigments. In addition to the exhibition title’s descriptive function, however, there is also something of an imperative. Like “slow food” and “slow fashion”, it implies that we should be concerned about the unsustainable speed of contemporary colour, positioning artists who use pigment ethically as the new artisanal sourdough or natural fibre clothing. The show’s explicit reference to temporality, but also its trendy eco-primitivism, present an interesting new development in the Workshop’s history and its commitment to keeping the art of tapestry contemporary.

The fact that the demographic of the artists skews strongly young and female supports the exhibition’s zeitgeist-y vibe. Two recent graduates of RMIT’s Honours program, Yolanda Scholz Vinall and Hannah Hall, both work with found or op-shop acquired fabrics while Wiradjuri artist Jessika Spencer and Toronto-based Shao Chi Lin weave fibre to produce three-dimensional works. Hayward and Jobson have brought works by these younger artists into conversation with the more established practices of painter Jahnne Pasco-White, Swedish weaver Katja Beckman Ojala, and ceramicist Yoko Ozawa. In doing so, they have demonstrated how artists like Pasco-White are helping to shape an emergent local discourse, while also productively contextualising the work of emerging artists like Hall and Scholz Vinall within this discourse.

Slow Colour, installation at Australian Tapestry Workshop, 2025. Photo: Tom Hvala

The exhibition is also intended to promote the ATW’s recent investment in a new R&D arm, in the person of natural dye expert Heather Thomas, who has joined Tony Stefanovski in the Workshop’s custom dye lab. Since it was founded in 1976, the ATW has produced large scale tapestries on commission for private collections as well as public institutions and government buildings, including Parliament House, the NGV, the Sydney Opera House, and Australian embassies worldwide. Working with artists to realise either a new design or (more often) a scaled-up tapestry version of an existing work, Stefanovski and the Workshop’s weavers create custom mixes from their in-house library of 368 yarn colours to produce a precise colour palette. Chemical dyes are environmentally destructive: synthetic dyeing processes used in the textile industry do not only require large quantities of water, they can also release heavy metals and other serious pollutants into wastewater. However, these dyes also produce stable and long-lasting colours, and are therefore suitable for the high-profile commissions the ATW undertakes. Natural dyes produced from plants are less predictable and more prone to fade or change over time. The Workshop’s new interest in natural dyes, therefore, could potentially open the door to a radical shift in the thinking that underpins their business model. Rather than the expectation that an artwork will endure the decades unchanged, perhaps artists and commissioners could conceive of a tapestry designed to embrace entropic change and weather gently over time?

The DIY, plant-based textile colours on display in Slow Colour draw from old-fashioned dyeing traditions while also being very of-the-moment. They are also actually faster (rather than slower) than synthetic dyes, in that they more quickly become subject to temporal decay. The works are slow and fast (or at least old and new) in several other ways too. Beyond the fact that each artist—like all artists everywhere—refers to or redeploys past artistic movements or traditions of making, there is an emphasis on indexicality or embodiment in their works that serves to articulate several distinct temporal positions.

Jahnne Pasco-White, from left: Kinning with Lake 3, 2024, lavender, plant-based crayons, oil pastel, watercolour, oil paint, raw pigment, dye, tempura, acrylic, silk, linen, cotton on canvas, 171 x 130 cm; Kinning with Lake 8, 2024, lavender, plant-based crayons, oil pastel, watercolour, reclaimed oil paint, raw pigment, indigo dye, tempura, natural dyes, acrylic, paper, pen, silk, linen, cotton on canvas, 183x 148 cm; Kinning with Lake 1, 2024, lavender, broad bean, spirulina, plant-based crayons, turmeric, oil pastel, reclaimed oil paint, coffee, tea leaves, raw pigment, indigo dye, tempura, natural dyes, acrylic, rice glue, paper, pen, silk, linen, cotton on canvas, 185 x 136 cm. Photo: Tom Hvala

Jahnne Pasco-White’s three large painted, soaked, and stained canvases are a stand-out of the show. Doing second-gen Ab-Ex again better, slower, with less stress and more humanity, Pasco-White’s work combines the modernist-informed compositional elegance of Helen Frankenthaler with the boss mum attitude of Jacinda Ardern bringing her three-month old to the United Nations General Assembly. Life and work are composted together in her practice of intuitive abstraction, which emphasises the indexical quality of Abstract Expressionism’s gestural mark. In a feminist expansion of the work’s remit, incorporating traces of the domestic and environmental alongside conventional studio materials, the artist regards her paintings as “an archive of sorts,” recording her experience of “being in the mess of life.” Yolanda Scholz Vinall and Hannah Hall’s works similarly accommodate diverse materials and techniques of making, indexing aspects of the artists’ lives and the circumstances of their works’ production.

Yolanda Scholz Vinall, Echoing Paths, 2024, avocado skins, avocado pips and red cabbage dye on recycled quilt cover with oil paint, ash and clay collected from Peramangk country, South Australia.Ceramic objects are stoneware glazed with Tenmoku or white glaze with ash. Dimensions variable. Photo: Tom Hvala

Scholz Vinall’s Echoing Paths (2024), like Pasco-White’s work, registers the artist’s personal life in its materials. The re-purposed quilt cover in Scholz Vinall’s work was coloured, in part, with dye produced from her sharehouse’s collected food scraps, and the work’s title also signals the artist’s interest in indexical mark-making. Tracing the path of her gestures, the splashes and stains of colour are outcomes of the negotiation between the artist’s intentions and the affordances of the material. Scholz Vinall departs significantly from Pasco-White’s approach, however, in her expansion into three dimensions. Several small ceramic pieces attach the draped fabric to the wall like a scarf pinned up with a brooch, or a partially drawn-back curtain. These effectively prevent Scholz Vinall’s textile from being read as a painting, bringing it into the decorative register of theatre, interior design or fashion, where art and life mesh.

Hannah Hall, from left: Hold It Together, 2024, natural indigo, mud dye, batik wax, handwoven cotton and thread, 31 x 35.5 cm; Rough Patch, 2024, ceriops bark, batik wax, handwoven cotton and thread, 61 x 45.5 cm; Spark, 2024, ceriops bark dye, recycled glass beads, handwoven cotton and thread, 61 x 45.5 cm; The Many Directions of the Heart, 2024, natural indigo overdyed with mud, handwoven cotton and thread, 76 x 91 cm; Roadblocks, 2024, jackwood overdyed with ceriops bark, batik wax, handwoven cotton and thread, 56 x 71 cm. Photo: Tom Hvala

Hall’s textile works, which are stitched and fitted onto standard rectangular stretcher frames, import decorative arts techniques into works that remain more firmly situated in the terrain of painting. As with Scholz Vinall’s work, Hall’s titles refer to the process of making, but also allude to the fact that repetitive craft processes can double as a therapeutic practice of emotional processing for artists. This series was produced during a recent residency in Indonesia where Hall learned batik and natural dyeing techniques using indigo, bark, wood, and earth pigments. The patterns produced using these techniques combine in this series with her signature use of pleating and stitching, resulting in heavily worked surfaces that are sometimes discordant and almost but not quite maximalist. I would love to see what would happen if Hall abandoned aesthetic restraint and pushed further into this territory.

Drawing on modernist and feminist thinking, artists like Scholz Vinall, Hall and Pasco-White place a slightly mystical value on direct experience. Natural dyeing processes, which typically involve the seasonal harvesting and preparation of local plants, perfectly articulate the indexical relation these artists construct between the work and the specific time and place of its creation. Their works seek to capture a moment, to soak it into fabric as an indelible mark or unique imprint.

Shao Chi Lin, from left: Superposition No. 03-103, 2023, paper yarn, myrobalan, pea flower, potato starch, 32 x 14 x 10 cm; Superposition No. 03-102, 2023, paper yarn, cutch, rice starch, 20 x 20 x 7 cm. Photo: Tom Hvala

Shao Chi Lin also uses a process of imprinting in her work, in which she has moulded paper fibre over 3D-printed armatures to form a series of small sculptures that look a bit like delicate egg cartons. However, her works do not register the circumstances of their making in quite the same way as the other artists in the exhibition: Lin seems to start with the cerebral rather than the material, seeking to visualise an idea rather than responding to materials at hand. With the collective title Superposition, Lin’s sculptures refer to the scientific study of interference patterns and amplification in wave forms. By giving form to vibrational impulses that would otherwise remain unseen, they also, in a different way, capture or diagram a moment.

Yoko Ozawa, Hai, 2024, stoneware, glaze, eucalyptus ash, 21 x 32 x 32 cm. Photo: Tom Hvala

A third temporal position is expressed in works by Jessika Spencer and Yoko Ozawa. Like the tapestries made by the ATW itself, their works are produced in an embodied practice that continually regenerates a living tradition of art making. Ozawa has used ancient Chinese and Japanese ceramics and glazing practices to produce works that evoke the Australian landscape, through crackled surfaces that shade from a powder-dry matt white to rich burnt terracotta and charcoal black. They are also in fact formed of the Australian landscape, specifically South Australian clay, which Ozawa has glazed with eucalyptus ash. Spencer’s series of small woven dilly bags similarly deploy ancient weaving techniques that the artist learned from cultural elders. Coloured with plant dyes sourced from both kitchen staples and local flora—including eucalyptus leaves, turmeric, stringybark, kurrajong, beetroot, and coffee—they present a pantry of materials drawn from the artist’s local environment. As Spencer has rightly observed, “Weaving isn’t just a fibre craft—it’s also got to do with land management and preserving culture.” This understanding of the intimate connection between embodied practices of art making, cultural preservation, and land management also underpins the work of other artists who use natural materials, such as Katie West, D Harding, ceramicist Kate Hill and senior artist Maree Clarke (whose work with her nephew Mitch Mahoney, Welcome to Country—Now You See Me: Seeing the Invisible (2024), commissioned for the new Footscray Hospital, is currently on the ATW’s loom).

Jessika Spencer, from left: Stringybark and Coffee Handle, 2024, woven dilly bag, 66 x 15 x 6 cm; Eucalyptus Leaves and Turmeric, 2024, woven dilly bag, 80 x 16 x 6 cm; Beetroot, 2024, woven dilly bag, 87 x 15 x 6 cm; Coffee Handle and Decaf Base, 2024, woven dilly bag, 80 x 15 x 6 cm; Red Onion and Turmeric, 2024, woven dilly bag, 70 x 15 x 6 cm. Photo: Tom Hvala

The artists in Slow Colour, drawing from Indigenous ways of knowing, second wave feminism, and a range of craft traditions, are in one sense making work that deeply aligns with the goals and motivations of the ATW. The Workshop was established in the 1970s, when feminist interest in neglected craft traditions was at its peak. Inaugural director Sue Walker, a weaver herself and also president of the newly formed Craft Association of Victoria, led an all-female team of weavers to set up the Workshop with significant support from high-profile arts philanthropists such as Dame Elisabeth Murdoch. They were responding to a demand from artists and architects for a practical means of producing large scale artworks suitable for public buildings. However, an ideological commitment to handcrafting was also woven into the organisation’s DNA from the start. Archie Brennan, director of Dovecot Tapestry Studio in Edinburgh, was in Canberra in the mid-1970s undertaking a Creative Arts Fellowship at ANU, and he acted as a key advisor to Walker. Dovecot was established in 1912 when it successfully poached two master weavers, Gordon Berry and John Glassbrook, from William Morris’s workshop. Emerging directly out of the British Arts and Crafts movement, the Studio inherited its nostalgia for medieval guild-style workshops and its criticality towards industrialised mass production, a legacy that was passed on to the ATW in the 1970s. The work produced by the artists in Slow Colour in a sense resurrects an Arts and Crafts-style advocacy for slower, more considered forms of making, and a model of production and consumption better able to support quality of life both for artists and for the audiences and consumers of their work.

Katja Beckman Ojala, Oldenburgerstraße (Bitte Nicht Abdecken), 2023, linen and ramie dyed with natural indigo, 220 x 65 cm. Photo: Tom Hvala

The ATW still enjoys the kind of heavyweight patronage from the local aristocracy that most arts orgs could only dream of, and it’s great that they direct some of this largesse to young, emerging artists through residencies and exhibition opportunities. However, the steady stream of lucrative commissions the Workshop relies on has seemingly also supported its own conservatism. The technical prowess of its weavers is frequently deployed in the translation of an existing image into the format of tapestry, which I imagine wouldn’t necessarily provide a lot of scope for the critical expansion of contemporary tapestry as a form. Swedish weaver Katja Beckman Ojala’s gorgeous, indigo-dyed Oldenburgerstraße (Bitte Nicht Abdecken) (2023) demonstrates, in contrast, how a high level of technical knowledge can inform the kind of creative play that extends and develops an art form. The surface of Beckman Ojala’s tapestry is partially obscured by hanging threads that the artist has left exposed, literally foregrounding the relationship between support and image that is definitional of tapestry as a form. Unlike the other two-dimensional visual arts, a tapestry’s image is woven into the structure of the fabric: there is no distinction between the image and its support. Beckman Ojala exploits the double duty performed by the coloured thread in a work that seems to conceal its face, but only in order to reveal something of its underlying structure. Her work exemplifies the kind of thoughtful contemporary textile practice that the ATW rightly supports through its exhibition program, but could also—I suggest—do more of itself. Apart from a small number of stand-out exceptions, such as Brook Andrew’s fascinating Catching Breath (2014), the majority of ATW tapestries are produced in collaboration with painters rather than artists who work critically or experimentally with textiles or other media. I hope the Workshop’s foray into natural dyeing might indicate a new openness to this kind of exploratory contemporary practice, a practice that could also take it back to its own artistic roots.

Anna Parlane is a writer and academic in Naarm, Melbourne.