Secret Cherry

Gabrielle Chantiri

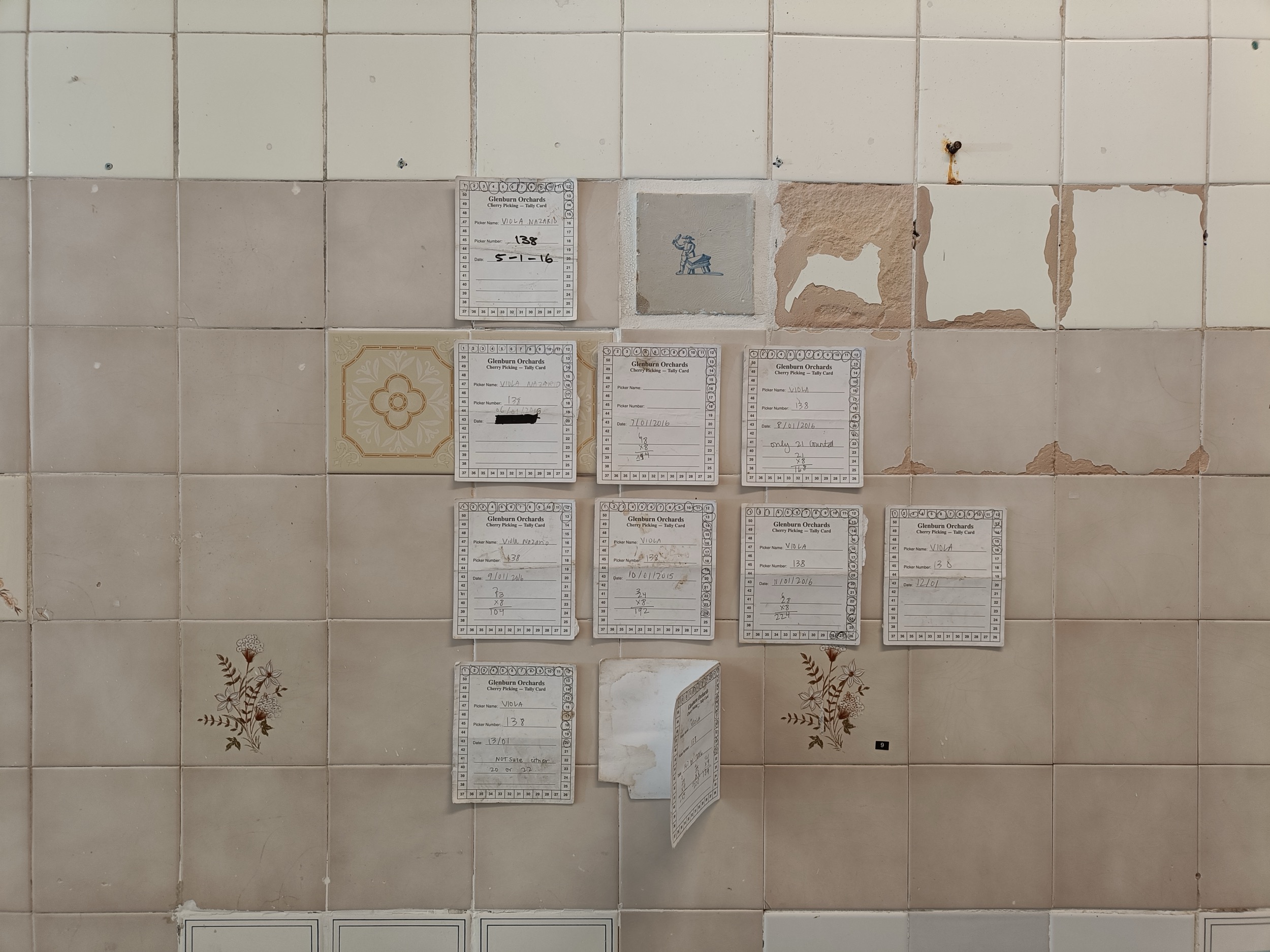

Between the harvest months of December and January, Benita Laylim and Viola Nazario go cherry picking. Their exhibition at Tiles Lewisham, Secret Cherry, appears to be a visual catalogue of these summers. Upon entering the space, the viewer encounters a cherry-picking harness hanging from the ceiling, a pair of pants floating in the window—the knees patched up and sown—and a shirt with a dirt-covered collar. Tally cards from past seasons are pressed into a grid on the wall, scribbled with the day’s equations and earnings. In a collaborative video work, Tarryn Waugh narrates the business of cherry picking. We’re unsure who he is in the context of the orchard, but he quickly earns our trust as he divulges a seasoned picker’s knowledge. At the centre of all this are Laylim’s clay paintings and Nazario’s works on copper, hung side by side on the walls, or leaning on purpose-made shelves. These works create a centripetal force with the aforementioned ephemera in the room, and yet they sit apart from the visual catalogue of cherry picking. I ask myself, “what are these works doing?”

We find our first clue in Nazario’s palm-sized works. Here oil paint is watered down with so-called “medium,” a compound of oil, turpentine, and resin. When painted onto copper, this medium produces semi-transparent colours. Like a rainbow, we can see through these colours, in this case to the copper sheet that is not so much underneath the paint but alongside or within it—like a mordant, the paint has provoked the copper to not only appear but to glow. As if to humbly shake her hands of any alchemical transmutation, brush bristles scumble the surface creating textured tracks. Nazario’s tactile approach to painting constructs oneiric landscapes for material deduction, allowing our eyes to rebuild the sequence of its making. Laylim’s clay tiles are also convincing as dream-like landscapes. As in Cherry Sleeper I (2024), the audience sees a cherry picker wrapped in swathes of cobalt blue that reminds us of water. However, unlike water, which leaks and spills, it holds its form. These elemental delineations between sleeper, blanket, cherry and horizon line appear to us out of the grittiness of the clay, a reminder that these works come to us out of duress, through the slow process of making pottery. Secret Cherry’s hang is reminiscent of a memory wall, or a dresser lined with rows of photos in oddly shaped frames. In Laylim’s work Orchard Bride (2024) a tile depicts a grove of bright green trees covered in netting, with an oval shaped ribbon used to create a vignette, while in Nazario’s Don’t Tell Me What’s Wrong With You (2024) and I Will Find Out and Tell You (2024) the audience can see the same oval shape this time made from wood. Together these works are nostalgic for something that can’t or won’t be forgotten. Perhaps this is what it means to be sentimental—there’s something inherently restless and unkempt about keeping the past so close. If we view the works as oneiric landscapes of cherry-induced mania, we might pretend that we haven’t been preoccupied with the works’ materiality, though we have been. The artisanship of these works is the product of working at a craft, but it’s also the product of social and labor relations, exchanges that characterise the lives of largely unsupported and underpaid artists.

In the collaborative work titled Secret Cherry Video (2024), the narrator Tarryn Waugh delivers a pertinent monologue on the business of cherry picking:

There’s a huge cherry industry and cause they’re so expensive there’s a lot of money in it. You get paid on what you pick, a dollar a kilo most of the time. When you get good at it, it rewards you. It’s difficult at first because you’ve got to get the cherries off with the stems on without breaking the spurs where they grow from on the tree because they don’t grow back if you break them. There’s a definite art to picking cherries. There’s a certain way in which the cherries come off easily, and a series of swift hand movements can bring in kilos into your bucket. You have to carry about 5 kilos sometimes 10 kilos, not as much as other fruit such as apples. You have a harness on which is connected to a bucket which you pick into and then you empty those into lugs, which can weight anywhere from 10 to 15 kilos, usually it’s a couple buckets for every lug. A good picker can make 50 lugs a day if it’s a good crop, but it really depends on what’s on the trees.

In this description, cherry picking is reduced to its weight in kilos, as well as dexterity. The likelihood of a good crop is calculable—for example, you can check the weather app to deduce whether a storm will sweep away an orchard before your eyes. The video catches the orchard on a good day, with a crew wearing wide-brimmed hats squinting as they ride along a dusty road in the back of a Ute. The sun is huge behind them as they walk into a grove staring at their feet and talking to the person next to them. Laylim and Nazario seem to pick cherries without touching them—they loosen invisible screws around the stems of the fruit and with a few deft turns the cherries drop into their buckets with a thud. Some faces smile big through the green leaves while others are immersed, caught by the camera mid-meditation. There is a simplicity in seasonal work, camping with friends and picking fruit. Our narrator likens the picker to migratory birds, descending on the orchards to pick and make money before moving on. The migratory nature of seasonal work is commonly associated with backpackers touring the country, but it is a less likely pursuit for those who reside here. Like the artist, the nature of seasonal work is not only familiar, but marked by being overworked and underemployed.

Secret Cherry displays ephemera associated with the orchard, or more accurately displays objects of production—the top and pants, the tally cards, the harness. When we read these objects in relation to Secret Cherry Video (2024), we’re given an inventory of a time and place. From this perspective it’s easy to view Nazario and Laylim’s artworks as simply part of the overall exhibition catalogue, for they are striking as depictions induced by cherry summers on the orchard.

However, occupied as we are by the materiality of the works, it becomes apparent that they express their doing and being done as opposed to merely representational, static depictions. As an example, previously Laylim has worked predominantly with porcelain, a material that shows the vividness of her stains and glazes more readily. In now working with clay, we see countless tests and hours would have gone into ensuring her stains, oxides, and glazes would be visible after firing. This artisanship is visible in the materiality of the works, the audience can see a craft that has been cultivated over time and alongside summers working in the cherry fields—or years punctuated by no cherry picking work or other work that isn’t guaranteed the following year. This is a familiar experience of emerging artists who are attempting to make anything that doesn’t provide a stable source of income, while simultaneously working fixed-term jobs (if lucky) with no real assurance of the jobs’ continuation. Secret Cherry materialises the labour and economic position of the artist attempting to live, work, and make.

Gabrielle Chantiri is a writer from Sydney.