Gallery collection, purchased through the Caltex Oil (Australia) Pty. Ltd. Acquisitive Art Prize with the assistance of the Visual Arts Board of the Australia Council, 1974.

Radical: Australian Abstract Art of the 70s and 80s

Loqui Paatsch

Warrnambool is the proud owner of a big thing from a not-too-distant future. Not a ram, not a pineapple, not a lobster. Although an unintentionally big thing, this tourist attraction is nevertheless an icon. Floating like a satellite atop the roof of the former Fletcher Jones wool factory is a silver orb that was once a water tower. It’s visible across Warrnambool, from the train tracks to the beach and many places in between. Constructed in 1967, the Silver Ball hovers on a red tripod-like structure forty metres above the ground. It’s the perfect space-age public artwork. Designed by Ralph Jones, an engineer and Fletcher Jones’ son, the sketched plans are simple and reductive. Safety consultants working on the project even stressed the importance of a maintenance ladder being “in accord (with) the design of the tank, which will be aesthetically pleasing.” Form over function, and form over fire safety. This is what the future was meant to be about.

Developed by in-house-curator Serena Wong, Radical at the Warrnambool Art Gallery presents abstract work from the seventies and eighties, drawn from the gallery’s collection (regrettably, the vast bulk of their holdings are unavailable to peruse online). As Radical’s exhibition text patiently explains, two far-out things happened in the late sixties: The Boeing 747 made air travel easy, cheap, and groovy, and a little exhibition in 1968 titled The Field opened in a stone shack on St Kilda Road and shoved Australian art into the contemporary, heralding a new wave of abstraction. Or something like that. Affectionally known as The Wag, the gallery began in 1886 and was later reinvigorated in the early seventies—post-The Field—by a local councillor-slash-baker who had a passion for amateur photography. Today the gallery is a pristine cube, complete with white walls and fronted by a well-maintained lawn with an out-of-place palm tree. Inside, front-and-centre in Radical is a hulking circular raku pot by Joan Campbell. It left me longing for the Silver Ball.

featuring Summer Garden by John Coburn and Shaped series #1, Shaped series #2 and Untitled (Shaped 2) by Elizabeth Gower, Warrnambool Art Gallery.

Radical orients itself according to the aforementioned Aquarian north star: The Field. The exhibition was the first to open in the National Gallery of Victoria’s new building in 1968. The key word here is “new.” New things are nice and new things are shiny. On the silvered walls and pale wood floors, The Field offered new artworks from fifty-three bright young things up to the public—a survey of artists (from Australia and elsewhere Anglo adjacent) working with the hip international style of hard-edge and colour field painting. Since day dot, the exhibition’s success (or lack thereof) has been contested. Often criticised for its conflicted attitude, either one of determined alignment with a waning modernist tradition or attempting to set itself apart from the existing history of abstraction in Australia. The newness wasn’t all that new, and not everything in The Field was what was said it was on the tin. Amongst all this post-painterly abstraction, there were minimal and conceptual works that hid in plain sight, lumped with stretches of flat colour and fixed pattern.

The Field has been reassessed and reconsidered with almost compulsory frequency in the decades following: The Field Now at Heide in 1984, The Field Revisited, a slavishly exact restaging of the show at the NGV in 2018, accompanied by a facsimile copy of the original catalogue, as well as other articles, rehashings, and studies too numerous to detail. The Field has something for everyone: provincialism, modernism, mirrors, controversy, feuds, and a whole heap of silver paint. On that note, rumour has it The Field’s silver walls were pinched from a show of geometric abstraction that the curator John Stringer saw at Leo Castelli Gallery in New York. This wasn’t an intentional choice on the NYC gallery’s part, but a relic from the previous exhibition of works by Warhol. More recently too, there’s last year’s Octopus 23: The Field (geddit?) at Gertrude Contemporary, which featured bursts of silver throughout, a tip of the cap from curator Tamsen Hopkinson to 1968.

Gallery collection, purchased through the Caltex Oil (Australia) Pty. Ltd. Acquisitive Art Prize with the assistance of the Visual Arts Board of the Australia Council, 1974.

Back to Warrnambool and 2024. Radical includes works by only four Field-ers, albeit heavily leaning on the exhibition for its focus: David Aspden, John Peart, Peter Booth, and Alun Leach Jones. They’re a nice bunch. Take Aspden’s Channels (1978), a suite of pretty yet sedative prints that see the transformation of his signature camouflage motif from the jewelled tones of the late sixties to isolated blobs in primary colours. Cute. Perhaps too cute. Cuter still is Stockade 1 (1974), a wobbly, vertiginous painting by Cecil Hardy (a non-Field-er) which does optical trickery very well indeed, all the while shimmying past any allegations of hotel-lobby-art often levelled at coy hard-edge abstracts. The slim frame encasing the work is painted in a metallic silver. This is a bit toy at first glance but delightful all the same. It’s complete and it’s comfortable. During my visit, I also popped into Wag’s other show. It’s the Gallery’s version of a blockbuster, a pairing of Mirka Mora and hometown hero Lisa Gorman whose work would be perfectly at home in a hotel lobby.

But I digress, back to Radical. There are two ceramic pieces: an untitled curvy figurative vase by Barry Tate and A World Within a World (1975), the previously mentioned random raku sphere by Joan Campbell. The two works sit uncomfortably next to Corvus (1965), a gorgeous small sculpture by Lenton Parr. It’s like housewarming gifts from a well-meaning aunt with little taste that you hide away only to pull them out on the odd occasion she comes to visit. Both pieces appear chosen for their formal balance or neatness. The roku sphere’s surface also shares a likeness to Mary McQueen’s The Banteng (1973), a fiddly and labour-intensive lithograph hanging to the pots’ left. In the opposite corner of the room is Elizabeth Gower’s Shaped series of collages (1980), built from patterned triangles of soft plastic and scrawled upon in poppy flat paint. Funky-constructivist-lite? Sign me up.

Alun Leach-Jones, another Field alum, was inspired by satellite images from the 1977 Voyager space mission. The silk-screened collages give a view of the heavens, a view that’s broken up into bits for transmission back to earth and reassembled in Melbourne as blocky distinct forms against grey ground. These register as serious rather than play school, because of the fragility and exactness that Leach-Jones treats these scraps of paper with: seeing beyond the stars to their forms, connecting spots and pinpoints of distant light into irregular prisms. A consideration of a still, airless world above our own, disturbing the natural scatter of the stars’ set order by filling in and solidifying the figures we make of them. Untitled, a thrilling and spooky 1971 painting by Peter Booth, is the standout: a sinister flecked arch in black and scarlet, glossy and soft around its perimeter, a looser version of his earlier rigid red rectangles, a peek through the doorway to darkness. Singled out as a romantic among the hard-edgers, Booth broke from pure swathes of colour into moody and fantastical figuration, populating his later canvases with lumpen figures, mystic animals, and apocalyptic gloom. Pity the fools who didn’t make it to last year’s Booth retrospective at Tarrawarra!

As for the show’s title, the word “radical” itself is something of a clanger. As the exhibition text acknowledges, abstraction was well and truly institutionalised by the seventies. The works contained within Radical are of disparate styles: a mash of shapes, angles, unexpected flatness, and patterns. They share the restricted vocabulary of sparse forms. Bea Maddock’s perplexing and brilliant screen prints are the most capital “R” radical thing on display here, or at the very least they’re the most disturbing. In Zig-Zag, a work from 1972, Maddock reworks newspaper images of a crowd, their arms collectively raised into a fascist salute. There’s a cropping and flipping and layering of each picture to form…well, a zigzag. Another crowd scene, Cast A Shadow (1972), is again filtered and distorted but this time by a minuscule and tyrannical grid. There’s no mention of politics in the petite wall text but placing these next to Untitled (1972), a swastika-esque tessellation by Sally Hartridge is certainly something.

Maddock’s great trickery is reworking these complex images in such a way that points not just at the porous, sticky qualities of abstraction, but its amnesiac qualities too. It’s a fraught relationship of both erasure and progression alike and signals the difficulty of possessing a memory which doesn’t always correspond to the facts. I think Radical pulls a similar trick. Despite pointing at the idea of The Field as a Big Influential Moment, Radical doesn’t examine the full sprawl of geometric or post-Field abstraction (whatever that means) per se. There’s no slick ironic minimalism here and no po-mo posturing. But it doesn’t have to. It’s not caught up in a future that didn’t arrive—the future the Silver Ball promised us—but one closer to home, the beginning of the future for Wag. Illustrating the gallery’s transformation from an assortment of nineteenth-century curios to an exhibition space and collection of contemporary Australian art.

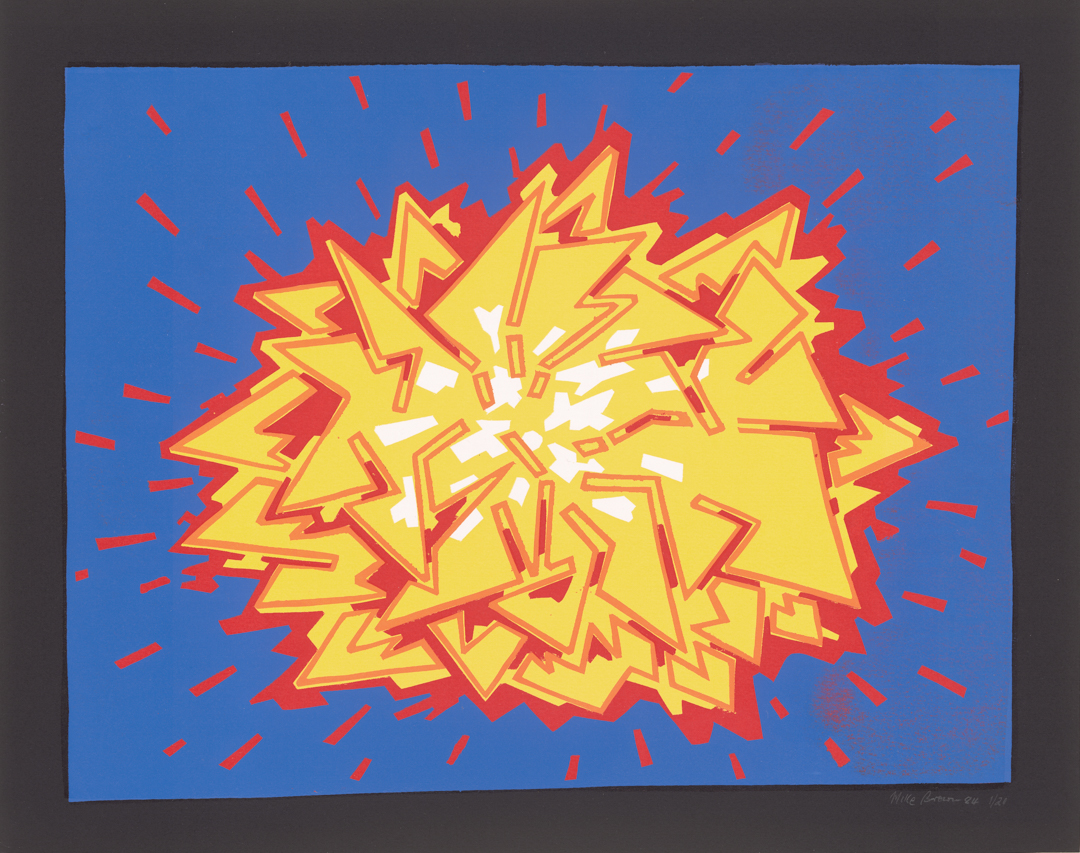

collection, presented through the Henri Worland Memorial Print Award, 1984.

Art historian Keith Broadfoot identified The Field’s crisis, and the broader problem of periodisation it posed in terms of tense prediction, “bringing Australian art not into the present, not even into the future, but into the rather odd category of the will have been.” This pronouncement reminds me of alchemist Roger Bacon’s brazen head, a soothsaying automaton that spoke of time is, time was, and time as past. The Field’s success lies in its failure, its wilful attempt to enforce a cohesion or trajectory which may not have existed, and which certainly the exhibition itself was incapable of realising. It’s both a poison and an antidote to institutionalised avant-gardes, to alleged provincialism, and the weak jolt of the proposed New. This falling apart is how things move forward, and yet we still can’t escape The Field. Someone’s locked the gate and had the fence electrified. Radical is by necessity a limited and strange survey, perhaps made more interesting for its pick-n-mix compilation quality, an awkward introspection that meets a version of an already narrow history. One that sits in the shadow of the Silver Ball.

Loqui Paatsch is a writer from Naarm/Melbourne.