INJURY x REAL PARENT, INTERMUNDIA, 2024, Mixed media installation with foamcore characters, garments, two-channel video, 1m 26s, courtesy the artists; photo: Kai Wasikowski for 4A Centre for Contemporary Asian Art, 2024.

NUW🌏RLDS

June Miskell and Soo-Min Shim

As if technology can bring liberation on its own—as when dreamed up in the fantasies of geoengineering technofixes and off-planet terraforming as capital’s best chance of survival (even beyond humanity’s own)!

— T.J. Demos, Radical Futurism: Ecologies of Collapse, Chronopolitics, and Justice-to-Come, 2023.

What is happening at 4A Centre for Contemporary Asian Art (4A)? Out with the old and in with the new: 4A’s 2024–28 Strategic Plan has arrived and it’s called #NuWorlds. If the hashtag is indicative of 4A’s desire to respond to the “pulse of the digital age,” it is unsurprising then that “digital transformation” is listed as the numero uno priority in their strategic plan (ahead of community and diaspora, scaled-up commissions and initiatives, international engagement, and sustainability and resilience). In their words, “key to 4A’s new strategic direction is exploiting the possibilities of Web3 and embracing new technologies with initiatives like the incubator space 4A LAB and our new online portal 4A+.” In this vein, 4A’s latest exhibition of the same name, NUW🌏RLDS, appears to be a hard launch of their new strategic plan #NuWorlds. Applying digital transformation as both an organisational principle and the guiding thematic for the exhibition, NUW🌏RLDS “consolidates and fully integrates 4A’s vision for the future.” Yet beyond the shimmering rhetoric of digital-optimism, what exactly is this vision and whose futures are at stake?

NUW🌏RLDS, 2024, Installation view, 4A Centre for Contemporary Asian Art; photo: Kai Wasikowski.

NUW🌏RLDS is a hybrid group exhibition curated by Thea-Mai Baumann and Con Gerakaris spread across three—physical and digital—locations: 4A in Haymarket, the adjacent 4A LAB, and 4A (a newly launched metaverse platform). According to the exhibition didactic, NUW🌏RLDS asks how “technology redefines our social, cultural, and personal landscapes, encouraging viewers to consider the evolving dynamics of identity, memory, and societal structures.” If that sounds vague, it may be because the text was generated through a series of prompts fed into ChatGPT—surprise! We don’t mean to rain on the parade of ChatGPT, but here it reads as a cop-out that exaggerates, rather than clarifies, clichéd dichotomies like “physical and virtual” or “tradition and modernity.” In a similar move, 4A registers their new “edge” by absorbing chronically online vocabulary and emojification in the title for the exhibition (building off yet distinguishing it from their strategic plan #NuWorlds). The trendier (barely shorthand) “nu” replaces “new” while the “o” in “worlds” is replaced with a globe emoji 🌏 that centres the exhibition’s geopolitical locus: the Asia-Pacific region. However, the exhibition has a much broader scope, as it connects a suite of artists whose digitally informed and speculative world-building practices often transcend the geospecificity that the emoji entails. 4A is the “server,” so to speak, aggregating #NuWorlds in their pursuit of the yet-to-be-determined future.

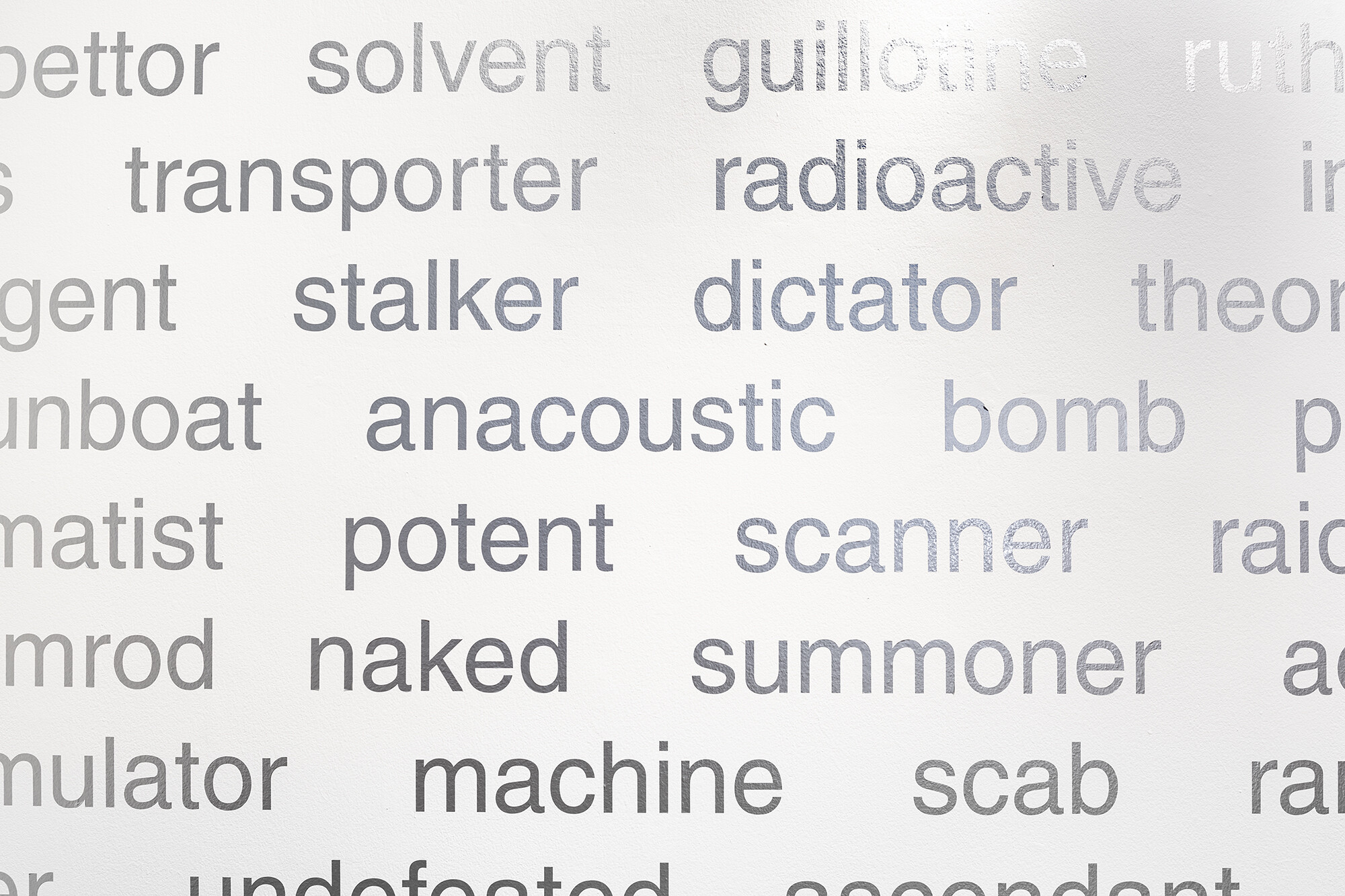

Raqs Media Collective, An Infra-Vocabulary for Capital, 2023/24, Vinyl on wall, courtesy the artists; photo: Kai Wasikowski for 4A Centre for Contemporary Asian Art, 2024.

Entering the gallery, the first thing we encounter is a glossary of terms in the entryway: AI (artificial intelligence), AR (augmented reality), Anthropocene, avatar, blockchain, CGI (computer-generated imagery), hacktivists, metaverse, NFT (non-fungible token), sentient, sinofuturist, technology, and volumetric technology. Ironically, the glossary of 4A digital terms needed to “decode” the exhibition seems to be parodied by the list of silver vinyl words applied onto the back wall of the lower-level gallery. These vinyl words are part of Raqs Media Collective’s installation An Infra-Vocabulary for Capital (2023/2024), which presents one thousand synonyms for capital. As if regurgitated by a bot, many of these words are derived from systems in late-stage corporate capitalism. Words such as “solvent” and “anthrax” evoke Big Pharma; “soldier” and “panjandrum” point to the military industrial complex; “transactor,” “taxman,” and “marketeer” are related to Finance and Wall Street. Most significantly, words such as “program” and “machine” are reminiscent of Big Tech. Interwoven into these sector-specific jargonistic terms are words that connote violence: “guillotine,” “torturer,” “chaos,” “bomb,” “dictator,” “abuser,” “conformist,” and “ravenous.” Together these words echo the contemporary conditions of collapse, serving as a linchpin to the otherwise hopeful language of digital transformation espoused by 4A for #NuWorlds.

Tùng Monkey, Tu Phu (Four Palaces - 四府), 2021, five-channel video, NFT, courtesy the artist; photo: Kai Wasikowski for 4A Centre for Contemporary Asian Art, 2024.

On either side of An Infra-Vocabulary for Capital are Tu Phu (Four Palaces – (四府)) (2021) by Tùng Monkey and Chengyu series (2009) by Laurens Tan. Both works attempt to grapple with the effects of urban and technological development on “tradition.” Tu Phu (Four Palaces – (四府)) by Tùng Monkey is a five-channel NFT installation that loops digitally manipulated recordings of artist and singer Hoàng Thùy Linh performing a series of gestural movements. While Linh’s choreography draws upon Vietnamese folk dance, her dress refers to Dao Mau (the spiritual worship of Mother Goddesses). According to the didactic, the work attempts to co-opt the financial function of Blockchain by retooling the NFT as an archival medium for cultural preservation. A quick look on Foundation (an Ethereum NFT marketplace) reveals that Tu Phu #2–#5 holds reserves between 0.2 ETH ($1000 AUD) and 1.00 ETH ($5,150 AUD) while Tu Phu #1 sold for 0.17 ETH ($875 AUD). While Monkey offers an intriguing proposition for the preservation of cultural knowledge, we remain sceptical about the paradox that lies in the commodification of such knowledge when it enters yet another, albeit “decentralised,” exchange market.

While Monkey places faith in the NFT to respond to Ho Chi Minh City’s changing identity as the so-called “Silicon Valley of Southeast Asia,” Laurens Tan’s Chengyu series (2009) addresses Beijing’s Haidian District, the so-called “Silicon Valley of China” through architectural characters. Tans’ 3D-rendered buildings mimic the skyscrapers found in the Haidian District. Tans’ buildings hover in space, angled towards the viewer so that we are able to see the underside of three buildings that have been carved out with four character idioms known as Chengyu. One of the idioms, De Guo Qie Guo (得過且過), connotes the idea of one “blindly following a path,” while another, Hotel Utopia a Dusk (左右為難), is translated to “I don’t know my left from my right.” These Chengyu then transform the grandiose architecture of tech cities into empty signifiers. By doing so, Tans seems to question the mindless, destructive march towards “progress” in the name of technology and “digital futures.”

Laurens Tan, from Chengyu series Zhong Guo Te Se (中國特色) Chinese Identity, a 2009, 3D modelled photomedia editioned inkjet print on Archival Fuji Fine paper Edition 2/8, Courtesy the artist; photo: Kai Wasikowski for 4A Centre for Contemporary Asian Art, 2024.

As we move upstairs, the provocations on the use of digital technologies to secure the future by Raqs Media Collective, Tùng Monkey, and Laurens Tan are abruptly left behind in favour of more ambiguous and fabulative digital world-building. The first work we encounter is Intermundia (2024) by INJURY x REAL PARENT, which centres on a CGI fashion show. Intermundia comprises three life-sized foamcore cutouts pinned to the wall alongside their physical garment counterparts, bearing resemblance to magnetic dress-up dolls. At the far end of this melange is a two-channel video animating avatars BELLE, E-BOY, and REAL, who fashion digital renditions of the denim blazer, pants, and sheer dress that hang in physical space. The verbose didactic can be whittled down to “technological advancements in design” and “innovative fashion design.” Here, we find a buzzword deployed by Big Tech and staunch defendants of the digital—innovation, blegh. Intermundia certainly applies novel technologies to fashion, but innovation, which more accurately might be defined as providing meaningful solutions to meaningful issues, is not synonymous with novelty. Under the supposed aegis of “innovation,” the digital risks slipping into ornament.

INJURY x REAL PARENT, INTERMUNDIA, I 2024, Mixed media installation with foamcore characters, garments, two-channel video, 1m 26s, courtesy the artists; photo: Kai Wasikowski for 4A Centre for Contemporary Asian Art, 2024.

At first, we wondered if NUW🌏RLDS’ emphasis on worldbuilding was a strategy to mitigate the myriad of interconnected socio-environmental violences that accompany the digital technological development: ongoing displacement, climate crisis, ecocide, necropolitics, resource extraction, e-waste, to name a few. However, 4A largely turns a blind eye to such issues, hedging its bets instead in the promise of virtual worlds to remedy the uneven power relations that remain in this one.

While the physical space offers no explanation as to why the design duo Eugene Leung and Dan Tse behind INJURY digitally render their clothing, their bio on 4A+ provides some explanation. The use of digital clothing simulation “cut(s) down carbon emission and wastage during the usual clothing sampling process by 80%.” Such a celebratory statement echoes corporate greenwashing rhetoric. While the fashion industry cuts down on sampling waste by turning to the digital simulations, it is worth asking whether this statistic considers that 3D rendering, much like AI and NFTs, requires an immense amount of hardware, electrical energy, and processing power. After all, electricity and heat production are the largest culprits contributing to carbon emissions today. INJURY’s proclaimed model of sustainability vis-à-vis the digital warrants further interrogation. Beyond selling physical collections and garments, INJURY creates and sells several wearable NFTs, which have now been publicly and widely known to have a large carbon footprint, exposing the fashion industry’s contradictory entanglement with capital.

aaajiao, bot, 2017–18, single channel video, colour, 15m 32s; Website, courtesy the artist; photo: Kai Wasikowski for 4A Centre for Contemporary Asian Art, 2024.

As INJURY celebrates the power of hyper-technologisation to transform the fashion industry, the video works on the opposite wall by aaajiao, the virtual persona of artist Xu Wenkai, sound a warning against hyper-technologisation. In bot (2017–18), aaajiao overlays a number of digital interfaces, from social media feeds to hand-held footage of bicycle rides and walks in parks in Shanghai and Berlin (where the artist is based). Finally, images of nature, mountainous terrains, and regions are amalgamated into a digital collage, revealing how the digital world actively shapes our perception of reality and identity. In aaajiao’s words, “I am a user, so what I am—how I understand the data that surrounds me, or what can be referred to as new memory system—consists of my body and the smart devices that extend from it, as well as the social media that stores my traces.” However, unlike Intermundia that praises the collapse between the digital and the physical by creating a visually alluring, fashionable universes, bot creates a hellscape. The various images flash across the screen at a dizzying, nauseating speed. Screens are split in half by endless, infinite scrolls of twitter and Facebook feeds that churn out limitless content. The epileptic editing suggests a reflexive nod towards the dangers of digital authority, the pageantry of the attention economy, and ultimately the emptiness of digital simulation.

Corin Ileto and Tristan Jalleh, Lux Aeterna, 2023/24, Mixed media installation with three-channel video, 2m 52s, courtesy the artists; photo: Kai Wasikowski for 4A Centre for Contemporary Asian Art, 2024.

Like aaajiao, Corin Ileto and Tristan Jalleh’s video installation Lux Aeterna (2023/2024) presents a complex tone of ambivalence towards “digital futures.” Despite the didactics’ insistence that the pair look to a “new existence beyond our physical place,” Lux Aeterna seems to do the very opposite—lament the demise of our current, physical earth. The title of the work itself, Lux Aeterna, is a common elegy used during Roman Catholic Requiem Mass for the deceased. We register this death in Jalleh’s employment of geological motifs in the video, where the landscape consists of husks of fossilised ammonites, globules of inky blackness that resemble oil, the ragged forms of obsidian and shell limestone, and mountains of sand. These materials are the atomic, molecular make-up of the earth on which we currently reside, and the detritus and debris of the earth we currently destroy, not to mention the core cog in the machine of technological development. Corin Ileto’s haunting, ghostly soundscape composed of deep, grumbling synths is reminiscent of Gregorian chants and heightens our awareness of a dying earth. Ileto plays on a keyboard made of obsidian keys that protrudes from a rock face, as if to evoke the sounds of the earth. Above her, metal tubes writhe like worms, perhaps evoking the e-waste that pollutes the earth. As such, Ileto and Jalleh’s world is not so much “otherworldly” or an “alien world” as it is a sombre and speculative projection into our burning, charred, and desolate world.

4A+ (4A’s new metaverse platform). Screenshot: June Miskell and Soo-Min Shim.

Moving between the various rooms in the exhibition culminated in feelings of disorientation and cognitive dissonance. The same feelings lingered when we turned to 4A+, an interactive Web3 platform that comprises the online component of the exhibition. On the landing page, we are encouraged to “fly around to explore” the “borderless, dedicated arena for artistic experimentation and innovation.” The metaverse world here contains digitally rendered works by INJURY x REAL PARENT, Tùng Monkey, Lawrence Lek, and aaajiao. Tùng Monkey and INJURY x REAL PARENT’s 3D rendered chrome forms rotate and hover in space slowly. The screens that hold the video works by Lawrence Lek and aaajiao also float in this immersive but empty void. For an online world, there is hardly any interactivity beyond flying around these virtual installations or viewing the digital catalogue of 4A Library (though no text is readable online). The lacklustre features of this digital realm may be attributed to the fact that 4A+ is in BETA mode (where it is feature-complete but now in the testing stages), and “BETA mode” seems apt to describe 4A’s new reboot via #NuWorlds and NUW🌏RLDS.

Further testing and development are needed to see the #NuWorlds’ Strategic Plan come to fruition. Their hard launch in the physical realm, the NUW🌏RLDS exhibition, is certainly indicative of a first BETA test: vacant and unresolved. While the exhibition attempts to tap into the potentially emancipatory and liberatory praxis of world-building, it is important to remember the power of world-building lies in its provocation towards a deeper and heightened consciousness of the current world, not a disengagement from it. As tragic and violent as this world is, we would rather stay here and better (not BETA) it.

June Miskell is a contributing editor of Memo. Soo-Min Shim is an arts writer living on Gadigal land and is a PhD candidate at the Australian National University.