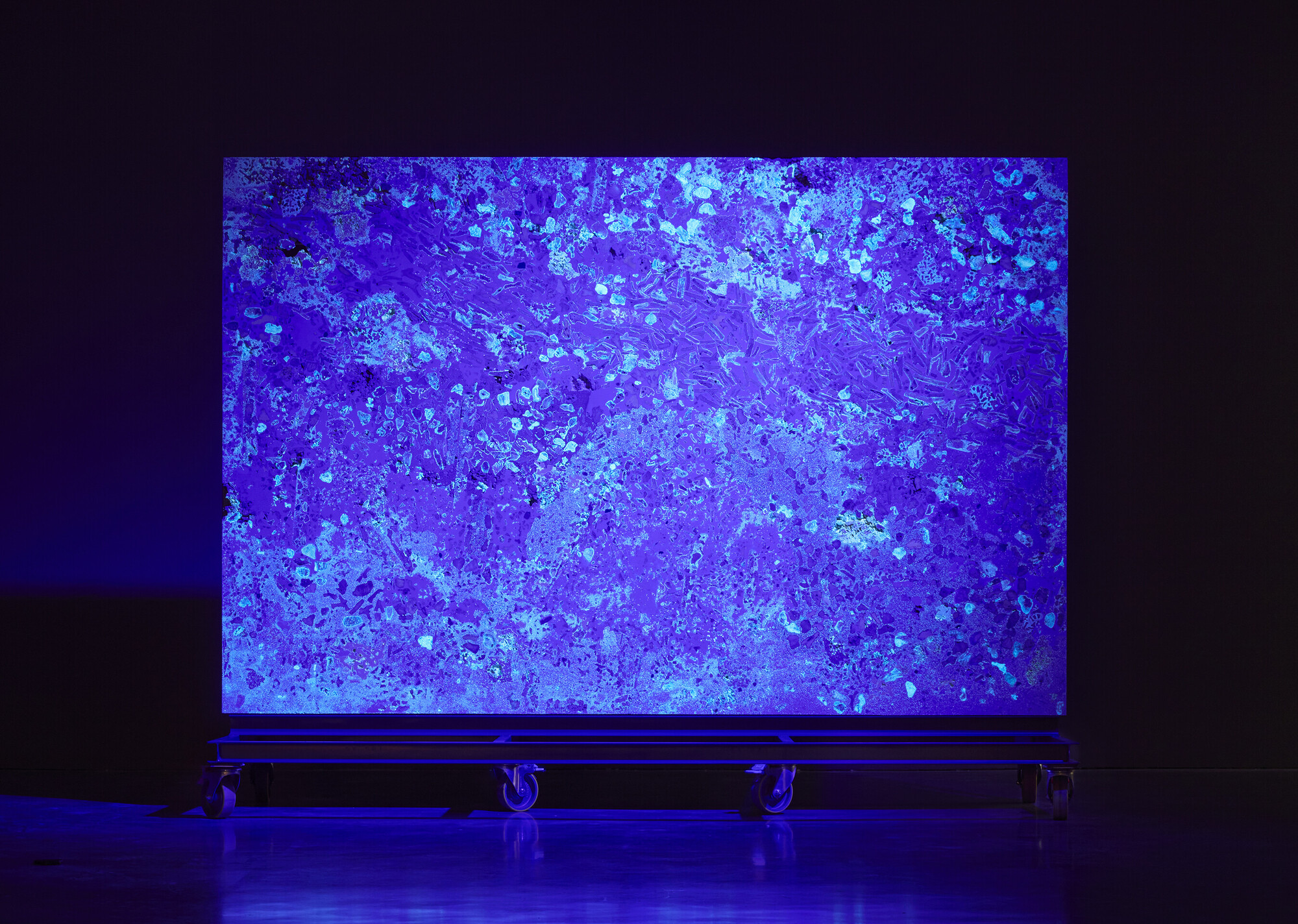

Nicholas Mangan, Death Assemblage (detail), 2022, coral, aragonite, mineral powder, acrylic resin, bioluminescent pigment, ultraviolet light, fibreglass-reinforced plastic grating, mild steel, enamel paint, image courtesy the artist, Museum of Contemporary Art Australia and Sutton Gallery, Australia © the artist, photograph: Zan Wimberley.

Nicholas Mangan: A World Undone

Nick Croggon

The arc of the moral universe does not always bend towards justice. This much was clear last year, when a majority of Australians rejected the Indigenous Voice to Parliament, a proposal that sought to take a first very small step towards redressing Australia’s colonial history. In the lead-up to the vote, the “Yes” campaign urged voters to embrace a historical narrative of national progress, one that arced from the 1967 referendum, to the 2008 apology, and culminated in the Voice. For Professor Gary Foley, however, this narrative was a dangerous myth, one that obscured both the lack of actual improvements for Indigenous people over this period, and the alternative history of Indigenous activism and self-determination. The resounding no vote was ultimately a refusal of both these accounts. It expressed a desire by the majority of non-Indigenous Australians to remain in an empty, atemporal present.

The current exhibition of Nicholas Mangan’s work at the Museum of Contemporary Art Australia (closing this weekend) offers, in a modest way, a series of alternatives to this historically evacuated present. It suggests that art is today a crucial site for analysing the past and future, and offers the gallery as a place where history’s various forms—its loops, eddies and arcs of progress—might be presented for our consideration. The exhibition, beautifully curated by Anna Davis and Anneke Jaspers, with exhibition design by Ying-Lan Dann, is a complex proposition—one that, like previous exhibitions by Zoe Leonard and Tacita Dean that have shared the same gallery space, asks a lot of its visitors. It asks for time and curiosity.

Nicholas Mangan: A World Undone is that rare thing: a mid-career survey of an Australian artist. Mangan began his career in the early 2000s in Melbourne (where he is still based) with a series of grungy sculptures in which domestic or natural objects were overrun with jagged or bulbous abstractions. The present exhibition traces a distinct passage of Mangan’s work from 2009 to 2023, in which he adopted a new mode of what he calls “material storytelling”. The exhibition presents eight “projects” from this period, each of which uses an array of media to narrate a particular episode from the colonial history of Australia and the broader Pacific region.

Mangan’s “material storytelling” method links him to artists like Bianca Hester and Tom Nicholson (artists of a similar generation whose midcareer surveys are also overdue): non-Indigenous artists who combine sophisticated research with material experimentation to interrogate Australia’s colonial history. Yet while Hester and Nicholson often use performance to activate their stories, Mangan’s work is grounded in the language and history of sculpture. This is a point that the exhibition makes clear. Upon entering the exhibition, the visitor is immediately greeted by a low, ocean-blue platform on which stands two gleaming coral-limestone coffee tables, with a chunk of the raw material displayed beside them. Such opportunities to relish the texture and form of Mangan’s sculptures recur throughout the show, as Dann’s elegant and subtle exhibition design spotlights elements like the large papier-mâché disc in the Limits of Growth project, the intricate structures in Termite Economies, and the stunning wall of coral detritus in the exhibition’s final room.

Nicholas Mangan, Proposition for Dowiyogo’s Ancient Coral Coffee Table, 2009, installation view, Nicholas Mangan: A World Undone, Museum of Contemporary Art Australia, 2024, coral limestone from the island of Nauru, wooden travel crate, image courtesy the artist, Museum of Contemporary Art Australia and Sutton Gallery, Australia © the artist, photograph: Hamish McIntosh.

Nicholas Mangan, Termite Economies: Phase 3 (Rorschach) (detail), 2019, installation view, Nicholas Mangan: A World Undone, Museum of Contemporary Art Australia, 2024, 3D printed polymethyl methacrylate, resin, synthetic polymer paint, steel, plywood, custom lighting, image courtesy the artist, Sutton Gallery, Australia and LABOR, Mexico © the artist, photograph: Hamish McIntosh.

This is not, however, an exhibition of sculpture in the traditional sense. Rather, as Memo editor Helen Hughes has previously noted, Mangan’s sculpture takes place within the expanded field opened up by avant-garde artists in the latter half of the twentieth century. In the 1960s and 1970s, artists in the Minimalist, Postminimalism and Institutional Critique movements redefined sculpture to include a vast variety of new materials and processes, shifting its emphasis away from the ideal and towards the contingencies of the time and space in which it took place. Inflected by the radical politics of the moment, these movements also pushed sculpture to interrogate its discursive and institutional conditions of possibility. In Australia, these radical politics included a new wave of Indigenous activism (in which Foley played a key role), which reminded non-Indigenous artists that the land on which they worked, and into which their sculptural practices increasingly moved, was already infused with Indigenous history and sovereignty.

The eight projects presented in Nicholas Mangan: A World Undone unfurl within this expanded sculptural field. Each of the eight projects involves an “assemblage” of elements (objects, moving images, machines, images) that draw attention to the various forces (material, historical, economic) that have led to their creation. The limestone coral display mentioned above, for example, gathers together in a single punctum an image of Nauru, the island from which the material was sourced; the twentieth-century mining industries that colonised and stripped Nauru of its valuable resources; the flows of global capitalism that distributed these resources (and resulting wealth) across the globe; and finally the more recent utopian and dystopian efforts by Nauruans and Australia to imagine a future for the island.

Davis and Jaspers have curated Mangan’s eight projects to unfold in a roughly chronological manner. The exhibition’s first arm paces out six projects instigated between 2009 and 2016, tracing the moment in which Mangan first brought film into his sculptural practice. This took place in the wake of the Nauru project, and was explored in his 2015 PhD thesis at Monash University. As Hughes has explained, the artist’s incorporation of film into both his thinking and practice was a crucial step in opening his work to the analysis of history and time.

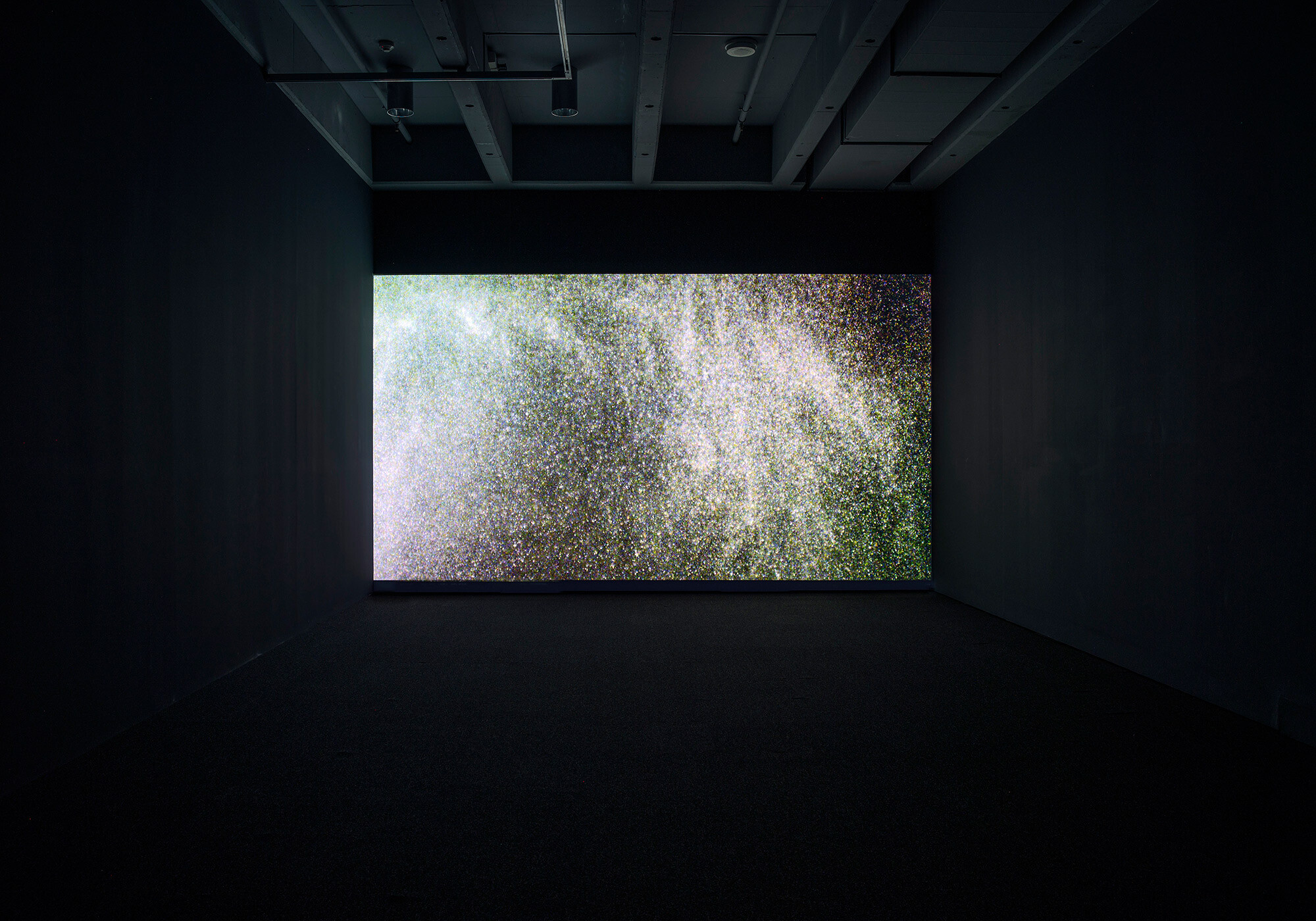

Nicholas Mangan, A World Undone, 2012. Installation view, IMA - Institute of Modern Art, Brisbane, 2016. Photographer: Carl Warner.

The key work here, and the one that gives the exhibition its title, is A World Undone (2012). Here, Mangan used a digital camera to capture in slow-motion the billowing descent of a puff of glistening zircon particles, a mineral formed 4.4 million years ago as the earth was solidifying. Standing in the deep dark of this work’s screening room, the visitor witnesses the collapsing together of two vastly different temporalities—the material formation of the earth, and the high-speed operations of digital image technology. Time here appears not as a single arc of linear progress, but rather as a vortex that spirals in and down, towards the beginnings of the universe and the microscopic operations of dust particles. In other video works in this section, Mangan uses montage to juxtapose others forms of time and history, which he then subjects to loops and reversals.

The exhibition’s second arm takes the viewer through the two major projects that Mangan explored in the wake of his PhD project: Termite Economies (2017-20) and Core-Coralations (2022-present). It is here that the political economy underpinning Mangan’s practice becomes most explicit. To create the works for Termite Economies, for example, Mangan probed various real and imagined ways in which the insects could be put to work: as gold detectors (a real CSIRO proposal), or as models for more sustainable modes of consumption, collective action or distributed decision-making. Mangan’s interest here is in the gap between humans and nature, which he understands as a founding gesture of colonial capitalism. As Mangan is well aware, however, in imagining ways in which this gap might be bridged, his method veers uncomfortably close to a form speculative capitalism that is forever seeking new terrains to colonise and exploit. The future is not an open field, this works suggests, but rather an already crowded marketplace.

Nicholas Mangan, Termite Economies, 2018-20, installation view, Nicholas Mangan: A World Undone, Museum of Contemporary Art Australia, 2024, image courtesy the artist, Museum of Contemporary Art Australia, Sutton Gallery, Australia and LABOR, Mexico © the artist, photograph: Zan Wimberley.

Mangan’s work is sometimes criticised for foregrounding interesting ideas, but ultimately lacking any aesthetic punch. Such critiques, however, miss the point entirely. In a polemic on sculpture way back in 1965 (“Specific Objects”), Donald Judd argued that new art must aim for something other than the transcendent aesthetic experience provided by modernist painting and sculpture. Instead, such work should aspire only to be “interesting”, denying transcendence and instead returning attention to the perceptual, material and historical complexity of everyday life.

In the exhibition’s final room Mangan seems to address this point directly. The darkened room includes a trio of works from his most recent Core-Coralations project, which focuses on the Great Barrier Reef. The centrepiece is Death Assemblage (2022), a large two by almost-three metre slab, tilted slightly backwards on a black metal frame that recedes into the darkness. The slab is an accumulation of dead coral fragments, held together by a glue of argonite (the base mineral in coral) and epoxy. The regular pulses of a UV light activates a bioluminescent pigment in the sculpture, producing a rhythmic glow of neon blue. The light is gorgeous, and invites the kind of transcendental experience that Mangan’s work usually denies. As Mangan has explained, however, the flash alludes to the light some corals emit in response to heat stress—a reminder that an escape into the aesthetic comes at a great worldly cost.

Nicholas Mangan, Core-Coralations, 2021–ongoing, installation view, Nicholas Mangan: A World Undone, Museum of Contemporary Art Australia, 2024, image courtesy the artist and Sutton Gallery, Australia © the artist, photograph: Hamish McIntosh.

Nicholas Mangan, Death Assemblage, 2022, installation view, Nicholas Mangan: A World Undone, Museum of Contemporary Art Australia, 2024, coral, aragonite, mineral powder, acrylic resin, bioluminescent pigment, ultraviolet light, fibreglass-reinforced plastic grating, mild steel, enamel paint, image courtesy the artist, Museum of Contemporary Art Australia and Sutton Gallery, Australia © the artist, photograph: Zan Wimberley.

The Core-Coralations room also performs a more subtle gesture. Interrupting the exhibition’s overall chronological structure, the coral slab hearkens back to the coffee tables at the entrance. In the Core-Coralations room, moreover, the rectangular form of the coral slab is rotated across the gallery, appearing first as a horizontal slab, flipping up onto the wall to take the form of a digital screen, and finally settling on the floor as a surface to present more sculptures. The exhibition frames Mangan’s most recent work not as the culmination of his practice, but rather as a re-articulation of the forms and means (film, image, sculpture) that have defined his work since 2009.

Indeed, perhaps the most impressive aspect of Nicholas Mangan: A World Undone is the way it manages to reflect Mangan’s combinatory methodology at the level of the exhibition itself. As the exhibition catalogue reveals, each of Mangan’s research projects produces an avalanche of images, documents and objects. In the exhibition itself, however, Davis and Jaspers have carefully selected only a few elements for each project, choosing those that point to the formal and material links between the projects. The exhibition appears as one giant Mangan assemblage.

Nicholas Mangan, Limits to Growth (Part 3) – Letter to Rai, (detail), 2020–21, installation view, Nicholas Mangan: A World Undone, Museum of Contemporary Art Australia, 2024, steel server rack, reconstituted aluminium and cables from Bitcoin mining machines, archival pigment print with aluminium frame, papier mâché sculpture made from 149 shredded photographs Courtesy the artist and Sutton Gallery, Australia © the artist, photograph: Hamish McIntosh.

Nicholas Mangan, Ancient Lights, 2015, digital print on photographic paper, image courtesy the artist, Sutton Gallery, Australia and LABOR, Mexico © the artist

In framing Mangan’s practice so expertly, the exhibition also, however, exposes its limits. In a public program accompanying the exhibition, Mangan was paired with Pacific Studies scholar Katerina Teaiwa. Teaiwa’s academic research and art project Project Banaba (2017-) in many ways mirrors Mangan’s own, in its exploration of Oceanic histories of extraction and circulation. Yet Teaiwa’s work, drawing on her own personal history and recent developments in the broader field of Pacific Studies, seeks ultimately to craft an Oceanic understanding of history, one that centres local Indigenous voices, languages and worldviews. Mangan’s interrogation of history, in all its richness and complexity, remains nonetheless embedded in colonial structures: the book/research paper, the archive, the research institute, and finally the Museum itself. The exhibition ultimately leaves Mangan with a very interesting problem to solve.

Nick Croggon is an art historian, writer and editor based on Gadigal and Wangal land. He is Events and Programs Officer at the Power Institute at the University of Sydney.