Jean Valette-Falgores Trompe L’œil, c. 1770s

NGV Permanent Collection: Decorative Arts

Gemma Topliss

I had intended to review Lesage x Vionnet, the couture embroidery exhibition from NGV’s Krystyna Campbell-Pretty AM Fashion Research Collection. But, due to some publishing error in Art Guide, it had already been taken down when I arrived. The space was cordoned off, cut wires hung limply from the wall, and empty plinths were huddled in one corner. Instead, I retreated to the permanent collection.

After wandering the passage that overlooks the Great Hall, I recognised something I had seen before: three trompe l’œil paintings from the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. One is Jean Valette-Falgores’ Trompe L’œil (1770s), a classic example of the genre, a painting in which various objects appear nailed to a wooden board. Boards or letter racks were the preferred subject for trompe l’œil, as their flatness and opacity helped create a convincing illusion of a three-dimensional surface. It also allowed for the inclusion of printed or written matter, marrying a private handwritten letter, for example, with a printed reproduction. The interplay of public and private subject matter mirrors the technical exercise in perspective and depth. Valette-Falgores’ painting includes depictions of printed and written ephemera alongside a mathematical compass, feather, flute, key, and butterfly.

Including a butterfly differentiates the items not just by depth but by vitality. The task of trompe l’œil is to imitate life so perfectly that one is deceived. Pliny the Elder tells the renowned story of Zeuxis and Parrhasius and their contest as two established painters in the trompe l’œil tradition. Zeuxis paints a bowl of grapes so lifelike that birds swoop down to peck at them. Parrhasius goes off to paint his retort and returns with his painting covered by a curtain. Full of anticipation, Zeuxis asks Parrhasius to draw back his curtain and unveil his painting. Parrhasius then reveals that the painting is of the curtain itself. While Zeuxis was able to deceive the birds, Parrhasius is, of course, declared the winner, as he was able to deceive an artist.

Amelia Gill, Sam, 2024, oil and tempura on panel.

Trompe l’œil strikes me as being of the moment. The Prada SS25 collection featured leather-look belts appliquéd to the pants of the models (Look 7), dresses with permanently askew sleeves to suggest windswept chicness (Look 1), and false collars in colour-contrasted cut-outs (Look 9). Even the collection’s title, Infinite Present, echoes how trompe l’œil captures an infinite present by suspending a single moment. Another function of trompe-l’œil was the desire to capture one’s belongings, as in the case of King Louis XV, who commissioned Jean-Baptiste Oudry to produce 1:1 scale paintings of his hunting trophies, mainly deer antlers. Viewed in relation to this anecdote, Prada’s re-imagining of trompe l’œil is saturated with irony. A luxury belt, a status symbol, that is essentially a farce. It may deceive for a moment, but it is ultimately a stand-in for the real thing, an illusion.

In MADA Now at Monash University, paintings by Honours student Amelia Gill suggest a trompe l’œil resurgence. Like Valette-Falgores, Sam (2024) features a wooden board as its background, on top of which sits a bundle of sticks on a ledge, bound with ribbons that neatly form X’s. Gill’s paintings, unlike their traditional counterparts, are spatially disrupted. Untraditionally, the images are cropped to disrupt the illusion of a contained pocket of reality. The ledge painted in Sam continues beyond the frame of the painting, breaking our perception of it as “real.”

Zoe Jackson, Hope and self-preservation, 2022

Zoe Jackson’s Hope and self-preservation (2022)—currently on display as part of Daine Singer’s group exhibition Hard Rubbish—is a small doll-like creature made up of miscellaneous textiles (I recognise the components of a grey marle hoodie and denim fabric) and two plastic NAB-sponsored piggy banks in the shape of ballet slippers. It sits upright, its “face” spiralling inwards as though enveloped in introspection.

It made me think about the financial literacy instilled in children via the piggy bank method of cash hoarding. It’s a lesson that relies on the premise that sacrifice and denial lead to delayed gratification. In Catholicism, martyrdom and sacrifice promise that our suffering in this world will be rewarded in the next. Small change adds up. Hope and self-preservation is presented on a plinth covered in cream felt, alongside Jackson’s other assemblages, also composed of found objects. It’s felt pedestal is reminiscent of the velvet bed on which the Medal for Valour lays. Its aesthetic language immediately translates as a military decoration, but it is an artefact of the Women’s Social and Political League (WSPU). It was awarded to suffragette Grace Chappelow for enduring her imprisonment and protesting her incarceration with a hunger strike.

Medal for Valour, 1909

Ursula Le Guin’s essay ‘The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction’ (1989) argues for the primacy of the container. Unlike a weapon, “the tool that forces energy outward,” the container is a “tool that brings energy home.” As such, she decries the tendency to liken the medium of the novel to a weapon with a sharp trajectory from point A to B. Instead, she argues that it collects, holds, and contains. The medallion of the Medal for Valour is engraved with the words “Hunger Strike.” A hunger strike is a double negative; hunger is an absence, and a strike is a suspension.

The image of the work on display at NGV is unavailable. This is a similar example from the Met.

The final thing to capture my attention is a late eighteenth-century Italian folding fan, whose centrepiece illustrates a volcano. Its silhouette is illuminated by searing lava, and the entire scene is flooded in darkness aside from what is made visible by the glow from the fire, which includes the river beneath it, a small tower, and a few boats. The volcano is flanked on either side by small circular vignettes of other landscapes. On the left is a hollow opening where a cliff meets the water, and on the right is a calm river cradling a small boat, foregrounded by a building with an archway and a turret. Unlike the intensity of the volcano, which holds the bulk of the visual weight, the rest of the fan is light, a lightness further inferred by the materials of its composition, ivory and chicken skin. I can only assume the volcano it depicts is Mount Vesuvius, given that it is Italian, and I found photographs of similar ones online from the same period. Coincidentally, Pliny the Elder died in the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in AD79, possibly whilst trying to save the life of a friend.

Hugh Crowley, Are You My Conscience? Cathedral Cabinet.

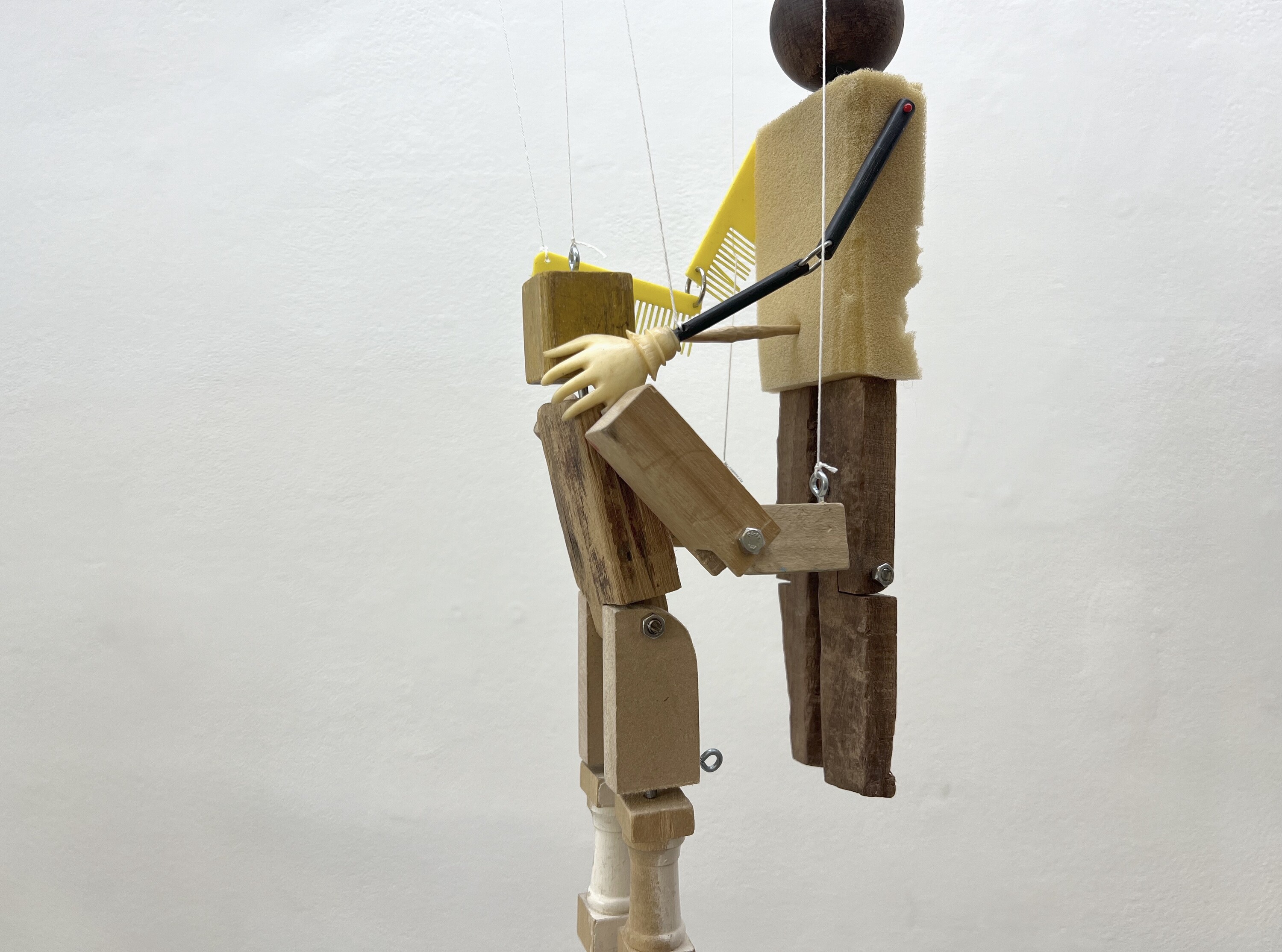

The eroticism of an eruption on a symbol of aristocratic femininity and a tool for flirtation is pushed up against the irony of cooling yourself down with molten lava. Fanning the flames makes a bad situation worse or more intense. All this sexual innuendo led me from the NGV to Cathedral Cabinet for Hugh Crowley’s current exhibition, Are You My Conscience? A collection of six marionette puppets sat in the window overlooking the highly patronised Cathedral Coffee. They are made predominantly of wood and found objects and hang suspended in the cabinet. Of the six, only one pair interacts, engaged in some rudimentary act of fellatio. There is plenty of obvious sexual innuendo to uncover here. After all, they are constructed of wood, and some are operated by a hand or fist inserted into a hole between their legs.

Artist Paul McCarthy also located erotics in the archetype of the puppet, featuring Pinnochio in his 1994 film Pinnochio Pipenose Household Dilemma. In it, Pinocchio’s extremities poke into holes of various sizes in his cardboard home. Pinocchio makes low and muffled guttural groans in this rendition as he dips his nose into a tin of chocolate sauce and other condiments.

The wires hanging from the wall at the closed exhibit were like loose threads. In missing the “real” thing, what presented itself to me instead were the threads that pull between past and present, illusion and reality, indecency and decorum.

Gemma Topliss is an artist and writer from Naarm/Melbourne.

This review was made possible thanks to the generous support of Meridian Sculpture.