Free to Forget; First Person Shooter; Peace Frog

Audrey Schmidt

Day 250 has passed. Once “the world’s most liveable city”, we now reluctantly embrace the new tagline of “the world’s most locked-down city”. Still, the humble house-show perseveres. Bound by indoor stasis, animated only by the flow of content across screens, the Lonely Planet exhibitions surveyed in this review are predictably tormented by the paranoiac consciousness cultivated by the giant hallucination machine that is the internet.

The twentieth anniversary of September 11 inspired rrealartt’s Free to Forget. The exhibition saw the remodelling of their mainstay plinth into two twin towers, which was posted intermittently on their Instagram over two days from September 11. As is rrealartt praxis, the show is entirely Instagram-based. In addition to a one-off screening of the attacks, projected onto the newly split plinths, the exhibition culminated in a digital exhibition of the US$10 million worth of art that was lost in the September 11 attacks—“Corporate America’s lost treasures”, says the exhibition text, also hosted on Instagram. It continues: “suburban living rooms enter the warzone via live television broadcast. We’ll never know whether it was news media that became Videodrome, or whether Videodrome became the news”. It is a welcome cue for me to play with dynamite.

David Cronenberg’s Videodrome (1983) was inspired by the heyday of the Public Access Cable Channel in the late seventies and early eighties, whose broadcasts operated outside Federal Communication Commission regulations. Like today’s social media, late-night cable producers were often creating and appearing on these independently produced shows for no direct income. When Cronenberg made Videodrome in 1983, he envisioned a kind of “interactive television” based on these contemporaneous technologies. Although a seemingly vintage line of enquiry, the Videodrome philosophy, or prophecy, has emerged as the cynosure of recent Melbourne house shows.

Videodrome is a speculative post-mortem of information induced mutation. In the film, the media prophet and creator of Videodrome, Brian O’Blivion, is modelled on Marshall McLuhan. He appears only on television in “his preferred method of discourse”—the monologue (think talking into your front camera abyss). Dead for some years, he now speaks from beyond the grave, solely interested in transmitting Videodrome intelligence with a view for humanity to evolve beyond the flesh and become pure information. O’Blivion aids the propagation of the Videodrome meme, which subliminally infects human circuitries so they converge with technological ones, altering reality. He sees it “as part of the evolution of man as a technological animal”. And just as man becomes technology, technology becomes man: tape and screen bulging, veins throbbing.

As “the future of television”, Videodrome is a plotless show supposedly broadcasting out of Pittsburgh that depicts real-life graphic torture and murder. See Squid Game (2021) after Battle Royale (2000) and Hunger Games (2012). Our hero/victim Max Renn wants to show the production on his cable TV channel, CIVIC-TV, but in viewing it, he unwittingly becomes a Videodrome test subject. “Whatever appears on the television screen emerges as raw experience for those who watch it”, O’Blivion explains. “The screen is part of the physical structure of the brain. Therefore, television is reality and reality is less than television”. It becomes apparent that it is the Videodrome signal, rather than the violent imagery, that produces the hallucinations, but the tone of those hallucinations is determined by the tone of the tape’s imagery. The hallucinations induced by the Videodrome signal become reality by mutating the physical body. “The visions caused the tumour and not the reverse”. In a literalised Baudrillardian sense, media images penetrate and mutate reality in such a way that they can no longer be said to be subsequent to or independent of the real.

The break-through allure of Videodrome is in satiating the desire not only to view the spectacle but to become the spectacle, peaking in the only true fulfillment of desire: flesh death. Today, the internet fulfills the Videodrome prophecy of interactive television, where war, murders and suicides are broadcast real time to large audiences of consumers looking for something to “break through” or click through. The tone of your hallucinations depend on the circular reinforcing connection between your viewing habits and your algorithm. But it is the medium and not the message producing your hallucinatory mutations that rewrites the act of viewership as an act of being. Just as the gun is the extension of the fist for Max, the phone is the extension of the hand for us. This is the prosthesis through which subterranean extremist groups can reap new human hosts for their philosophies with cult-like devotion.

Rival to O’Blivion’s cult of accelerated technological evolution is the Spectacular Optical corporation. It is “an enthusiastic corporate citizen” who makes “inexpensive glasses for the third world and missile guidance systems for NATO”. Its tagline: “keeping an eye on the world”. Claiming to be the true creators of Videodrome, Spectacular Optical seeks to destroy a segment of the North American population and assassinate O’Blivion’s network. For it, O’Blivion’s hallucinatory tool for enlightenment and revolution is an exemplary weapon. The reference is firstly to the tension between McLuhan-esque techno-utopianism and the manipulative power of military surveillance. But it is also a nod to the long and covert history of military experiments with psychoactive substances like LSD — and to McLuhan’s entanglement with Timothy Leary. Max, who has now absorbed the Videodrome technology into his nervous system, is robotically programmed and reprogrammed by these opposing forces; he is a pawn in the underground “war” between the tripped out libidinal would-be revolutionaries and the big guns calling the shots.

This same tension between the political optimism of the sixties, its perennial recuperation and military psyop, crops up in Liam Osborne’s solo show at Meow2, Peace Frog, which ran from 30 August until 19 September. The exhibition centrepiece is a large plywood peace symbol, For everything there is a season, rotating on its axis, leaving little floor space to navigate the rest of the exhibition. The hackneyed faces of Frank Zappa, Jim Morrison, Papa John, Stephen Stills, Gram Parsons and David Crosby printed in stencil-monotone on blotter paper peer out from deep-set frames painted black on each of the four walls. In the accompanying text, Osborne cites Weird Scenes Inside the Canyon: Laurel Canyon, Covert Ops & The Dark Heart Of The Hippie Dream by David McGowan as an influence behind these key figures. The book seeks to uncover the hidden history of military intelligence, European banking ties, murder, torture, mind control and occult happenings that coexisted with the sex, drugs and rock n’ roll within the Laurel Canyon hippie community of the Hollywood Hills. (One key example of military-art collusion in both the book and exhibition text, is the little-known fact that Jim Morrison’s father was an Admiral in the US Naval Forces, who was central to the known false flag Gulf of Tonkin incident that led to increased presence of United States militia in the Vietnam War).

The book and this exhibition contend that LSD was a tool for social control that co-opted the visual language of the peace movement. As controlled opposition, it was a movement that ultimately came to reinforce the status quo of American exceptionalism and sublimated political unrest. Gas tanks sit like bombshells in museological plywood enclaves alongside dismantled, hollowed out (mute) speakers. In Peace Frog, Osborne targets sixties music and hippie culture (and its intergenerational, international vibrations). His charge is that it represents the most dangerous operation of Imperial Soft Power.

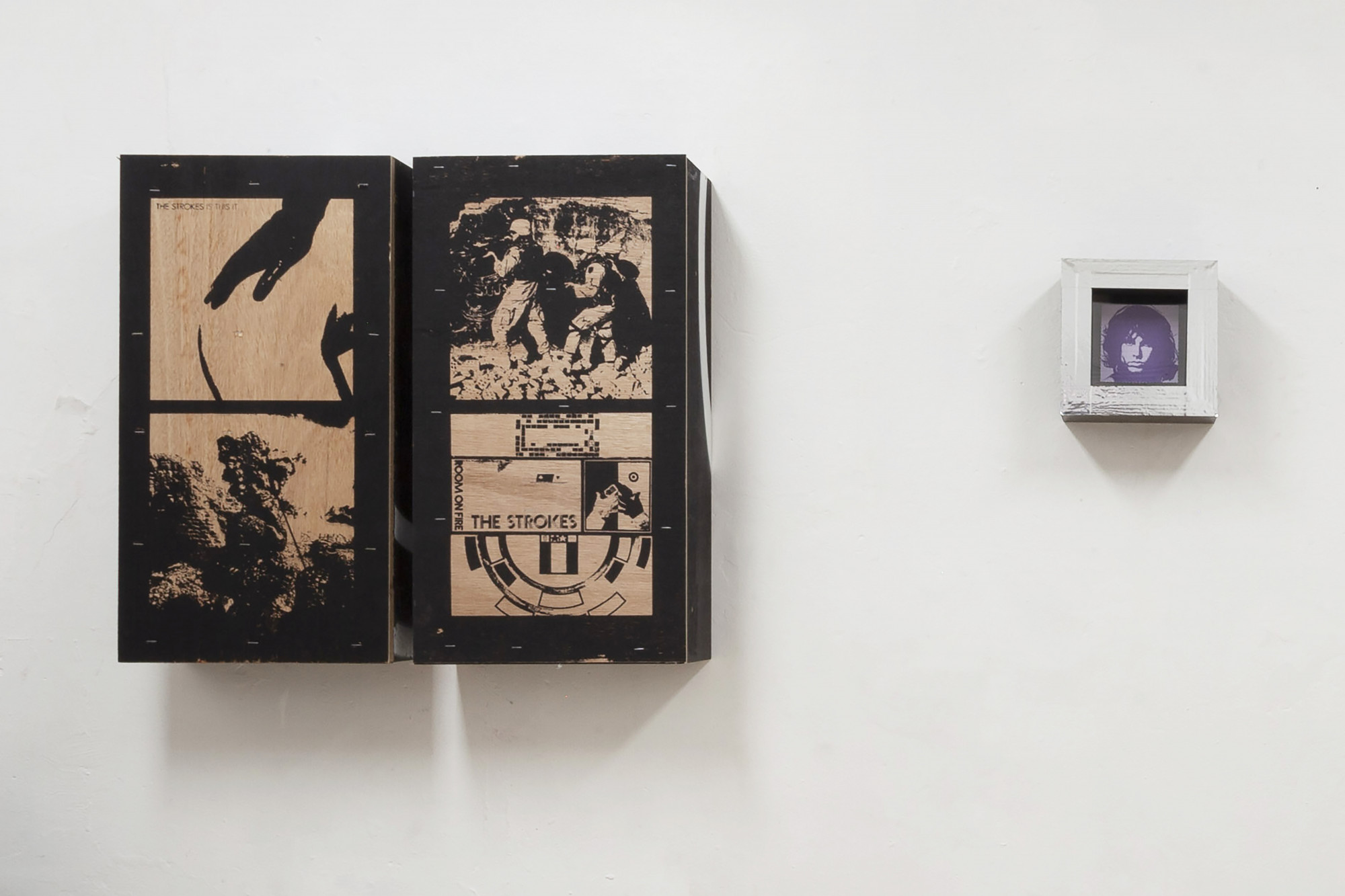

In the diptych 2003 (ROOM ON FIRE + IRAQ) and 2001 (IS THIS IT? + AFGHANISTAN), images of American soldiers at war are placed next to the first two studio albums by The Strokes: Is This It (2001) and Room on Fire (2003). Is This It came out just after 9/11 and RCA replaced New York City Cops with When It Started on the US album to remove any anti-cop sentiments in the wake of the attacks. Another song on the album, Soma, took its name from the hallucinogenic antidepressant in Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World (1932) which was weaponised to keep citizens anaesthetised to unpleasant social and political realities (Huxley himself named it after the ancient Indian Vedic ritual drink). The book’s punchline is that the development of vast mass communications is not concerned with truth but the unreal, and it indulges our insatiable appetite for distractions (as with drugs). None of this really comes across in The Strokes’ song, which is essentially just another love song, or distraction.

The Strokes’s second album, Room on Fire, copped a lot of criticism for being almost identical to their first, but it is significant to this exhibition because the band was licensed to use Peter Phillip’s 1961 War/Game painting for the cover art. The painting originally featured opposing Confederate and Union flags behind faceless men in uniform, cropped out for the four-decades-later Strokes album cover version. A band at the forefront of the American indie rock revival, inspired by Brit rock like The Rolling Stones and The Kinks, The Strokes are a superlative example of the intergenerational and international reverberations of sixties counter culturalism, emptied of any of the original’s already dubious political dynamism.

Peace Frog speaks to the enduring impact of (perpetual) war-time American culture on the international crisis—particularly the expansion of Empire by way of national emergency and the “sick voyeurism” of the Western media news cycle. Hitting the virtual newsstands just prior to Peace Frog was the fall of Kabul to the Taliban. Osborne made this a focus—particularly the event’s connection to Operation Cyclone, which set up the coordinates for the emergence of the Taliban and Al-Qaeda, leading directly to 9/11 and subsequent interventions in the Middle East. Centring clandestine operations and intrigues, Peace Frog illuminates the complicity of art and artists in maintaining rather than meaningfully challenging the status quo, inextricably entangling them in the long tentacles of global Imperialism. The exhibition is reaffirmation rather than protest, but it did good work chronicling, as Osborne writes, an environment where every cultural movement is “masticated by the state and fed back into itself”. In true Videodrome style, it linked “cultural revolutionaries” with industrial-military mind-control and raised the same question as rrealartt concerning the participatory sadomasochistic voyeurism of the news cycle: did news media become Videodrome or did Videodrome become the news?

First Person Shooter at the other house gallery of the Melbourne moment, Guzzler, was another on-theme pop-up of the last month. Listed on Instagram as a one-day exhibition on 5 September (posted on the 6 September), First Person Shooter was a collaboration between gallerists Alex Vivian (Cream Pot Charlie) and David Homewood (John McCrackpipe). The strength of Guzzler shows is that they are rarely visited. Located in Rosanna and installed for very short windows of time—generally between one day and two weeks—diminishes the prospects of IRL visits. It is the ideal Art Historian’s pet project. The success of each exhibition turns principally on impeccable documentation for dissemination and cataloguing. They’re exhibitions that are not really meant to be “visited” so much as “known about”, as the retrospective, day-late promotional material attests. Guzzler’s exhibitions are in this sense made for a future audience, the chronicler and historian, and have thus largely been unaffected by lockdown restrictions. It’s also a bit O’Blivion of them.

Immediately prior to First Person Shooter was another collaborative exhibition by the duo, Carbon Monoxide Room 3: Play At Your Own Risk (23–24 August). TVs wrapped in opaque plastic, like porn mag censorship at the gas station, were positioned around a similarly-wrapped box with a featureless white mask attached to it. A hose protruded from the mouth opening, connected to a car exhaust, and spewed out toxic gases into the empty gallery. As a one-day exhibition, happening in peak lockdown, it’s unlikely anyone attended the exhibition. The primary viewing platform is in an online visual essay on the Guzzler website, which can be viewed from the non-gaseous “safety” of your computer screen. Many of the videos and images embedded are more Blair Witch fabricated found footage than traditional documentation. They are intentionally obscure, dark, out of focus or totally scrambled. The signal rather than the imagery produces the hallucination of an exhibition. Yet key texts indicate its relation to the following exhibition such as: “MADNESS HIDES BEHIND THESE MONITORS … WILL YOU LOG ON?” and “REBOOT YOUR FRAIL CRANIUM AND INVITE ANNIHILATION – AN ORDER FROM McCRACKPIPE”. Here, media consumption is embedded in the Videodrome philosophy of “evolve or die”. Or maybe it’s “die to evolve”.

I’ve always said Guzzler is toxic but, like the Videodrome “snuff TV” show, this is literally a poisonous environment that promises to annihilate the audience should they choose to play. The apparent special effects of a smoke machine are, McCrackpipe tells me, real fumes. True Videodrome deception. By logging on and looking through your own monitor at the exhibition with scopophilic delight at the cryptic but ostensibly violent scene, you are already following McCrackpipe’s orders.

In classic gamer mentality, Max Renn’s justification for his lewd and sensationalist cable channel is that he gives viewers “a harmless outlet for their fantasies and their frustrations … a socially positive act”. Beyond the social media analogy, gaming is “participatory television” at its most literal. For those NPCs in the cheap seats, the “first-person shooter” (FPS) sub-genre of shooter video games centres on point of view weapon-based combat. Games like Doom were labelled “murder simulators” after it emerged that the perpetrators of the Columbine High School massacre were FPS gamers and their families unsuccessfully sued numerous video game companies. Perhaps the same could be said of the Saw-like setup of Carbon Monoxide Room 3: Play At Your Own Risk. Or is it a suicide simulator? Is it even simulated?

In First Person Shooter, a plastic gun painted white hung from the ceiling by a fishing line, pointed towards the entrance to the gallery, along with other “floating” objects including bleach, a used condom and a (fake) used tampon. The weapons have oozed out from behind the screen. Hanging from the ceiling, the objects were presented like a classic gaming inventory system to store and select items, or weapons lurking around waiting to be “picked up” in Call of Duty/Doom tradition. Guzzler visitors would first be confronted with the gun pointed at them but could then easily circle round to try-on the shooter’s perspective. But again, the only way to experience the exhibition is online, so we participate by allowing the “screen (to) become the retina of the mind’s eye”. The bulging screen with throbbing veins that Max Renn entered in 1983 Toronto has climaxed and left a used condom at Guzzler in 2021 Rosanna. But it’s ready to go again.

Explored through circular reasoning, both Videodrome and these exhibitions tap into the cyclical nature of the drives. The real source of enjoyment is not in reaching the impossible object of desire (truth or death) but in the repetitive movement around it. As Nicki Brand (Debbie Harry) puts it in the film, “We live in overstimulated times. We crave stimulation for its own sake. We gorge ourselves on it. We always want more, whether it’s tactile, emotional or sexual.” Vaxxed, waxed and ready to climax?

Talk of conspiracy theories is a little anti-vaxx, alt-right toilet-seat-Reddit-research in the paranoiac present. But conspiracies (AKA the secretive conspiring, scheming and collusion of powerful conglomerates, militia and persons) are indisputable occurrences, as Operation Cyclone, the Gulf of Tonkin and MKUltra have shown. As Joseph Heller wrote in his satirical war novel Catch-22 (another name for circular reasoning), “just because you’re paranoid doesn’t mean they aren’t after you”. The current mistrust of government and rampant conspiracy theory propagation should come as no surprise—particularly because, as O’Blivion forewarned, “reality is already half video hallucination”. For locked-down Melbournians, video hallucinations now occupy a more substantial fraction of O’Blivion’s ratio. In a state of emergency, starved of embodied encounters, these artists appear to be tuned in to the same sick, sad channel.

Audrey Schmidt is a writer and Melbourne Personality.