Ella Sowinska: 80 Ways; Meredith Turnbull: Closer; Zac Segbedzi and Friends (enemies) Early Career Group Show

Giles Fielke, Amelia Winata and Tiarney Miekus

Best and Overlooked of 2018

Memo Review asked three of our contributors to write on a show they have especially liked but that we haven’t had a chance to review. As a special issue we publish these reviews from Tiarney Miekus, Amelia Winata and Giles Fielke.

Ella Sowinska 80 Ways

recess, Friday 30 March – 30 April 2018

By Tiarney Miekus

Considering the amount of things that can be streamed online—i.e., entire lives—it's peculiar how art is a thing that supposedly doesn't happen on the internet. The reasons seem transparent; for some it's a kind of moralism, the belief that aesthetic transaction happens in the flesh, not the digital, or that something vital is lost in virtual spaces (even though many of the artworks I've felt to be profound were witnessed not in life, but in a more archaic form of reproduction: books). For others it's the nervous conviction that people will stop attending galleries and museums IRL, or, my more sinister suspicion, that non-commercial galleries and museums haven't yet figured out how to monetarise online space in the name of Art. The website is thus relegated to being the gallery's most essential promotional tool, and what makes the Naarm/Melbourne-based online publishing platform recess so valuable is how the website is the exhibition space.

Started in 2016, and co-organised by Nina Gilbert, Kate Meakin and Olivia Koh, recess is a site where you can stream moving image works. Each piece is given an exhibition date, and during this period is featured on the home page—after the 'show' is over the work moves to a side-bar, able to be streamed at any time. Extending the physical and temporal boundaries of the conventional gallery via an online publishing platform isn't necessarily a new idea, but for all its supposed obviousness, it's actually a rarity.

So far recess has shown 13 moving image works and, at the end of March this year, published 80 Ways by artist and filmmaker Ella Sowinska. It's an experimental take on personal documentary, where Sowinska films her mother—who writes online erotica under the pseudonym Sandy Mayflower—as she in turn films one of her self-published stories. The narrative is simple: it involves Claudia, who regularly travels internationally for her work on a water conservation project, and on each continent pursues a man for her sexual conquest. We get to witness flashes of this story, but our eyes are mostly directed toward Sowinska, Mayflower and the film crew, and we watch as they work with two actors to recreate the scenes of Mayflower's fantasies.

Amounting to a performed erotic space where the boundaries and power relationships between every person (actor, director, daughter, mother, lover) are continuously defined and re-defined, the central sexual encounter unfolds in every direction but sexy—desire and performance feel comic, excruciating and awkward, miraculously drifting between the utterly conscious and the completely unconscious. Two actors use their intuition to act out 'the deed', while Mayflower gives broad direction, enjoyably watching the pair. Meanwhile we look on as Sowinska watches her mother live out these fantasies, a view that reflects back onto the mother/daughter relationship and Sowinska herself. It's almost a therapy session, where the series of diegetic performances show each level performing stories and versions of reality, or articulations of desire, for another viewer. Yet the truly emotional and intimate moments of connection come when the performance fails or lapses.

If 80 Ways is broadly concerned with the circulation of unconscious desires, constructed situations and projections of fantasy, then it's perfectly placed in a space where such circulation is the modus operandi—a space where people are curiously determined to perform their best lives at every moment: the internet. There is an intensity to watching a short film on a device (laptop, phone, iPad) that's already carting around the huge anxieties and joys of performance, authenticity and desire—once you leave the film, you don't get any relief from the layered conflations of performance and intimacy; instead, it intensifies.

If 80 Ways had been shown in the neutral space of the gallery it would still be an extremely fulfilling work, but this intensity might not hold such gravity: the questions of performance and articulating desire wouldn't linger with similar urgency, or seem to connect so fluidly to lived experience. The importance of online context is relevant to encountering many of the works on recess. As well as widening publishing opportunities and critical accessibility, the greater triumph is how it provides moving image works a non-neutral and intensely loaded space, granting many of the videos more implicit and complex associations than what the white wall, or the darkened room, would be able to offer.

Tiarney Miekus is a Melbourne-based writer.

Meredith Turnbull: Closer

Ian Potter Museum of Art, University of Melbourne, Tuesday 27 March – 1 July 2018

By Amelia Winata

Meredith Turnbull's Closer was a two-part exhibition that presented objects from the University of Melbourne collection alongside photographic prints of those same objects. Spanning two galleries of the Ian Potter Museum, Closer acted as part of Turnbull's ongoing investigation into the blurred boundaries between craft and art with a capital 'A,' insofar as she questioned the status of the collection of functional objects both within the real space and then within the photograph. The objects were arranged sometimes in collections, such as a group of Czechoslovakian paperweights, but not in any particular historical manner. A collection of British pickle jars from the 1880s sat alongside a Chinese vase dating back to 1750 and an 'Etruscan bowl' from the contemporary Melbourne collective DAMP, dated 2013. Turnbull's photographs, each depicting one item from the selected collection pieces, lined the walls of the gallery. Set against background of bright monochromes or draped fabric, the photographs forced viewers to slowly experience the entire exhibition; viewers could not help but begin to match the object with its photograph.

Turnbull showed absolute respect to the many makers who had crafted these pieces—the bulk of whom were unknown. A lengthy (albeit somewhat difficult to follow) twelve-page room sheet labelled each and every one of the items with as much provenance information as possible—this process, too, demonstrated the haphazard past collecting styles of museums, insofar as many items had very little information. As a matter of fact, the feeling that these pieces elicited in the viewer was unexpected. I was deeply moved, for instance, by a small wooden sugar scoop by David Innes dated 1975–6. Displayed on Turnbull's low chipboard table, and affixed by a simple metal fastener, its existence as the product of skill and labour became breathtakingly apparent. Certainly, the artist appears to have been drawn to objects from the 1970s, a period that, most could agree, was not the height of objects of aesthetic value. Yet, Turnbull revealed that even these pieces, such as a 1971 garish blue stoneware urn by Alan Peascod, can also be beautiful despite their dated style.

Aside from investigating the lines (or lack thereof) between art and craft, there were actually more interesting micro-concepts at play in Closer that gave it nuance. Closer honed in on the notion of the museum as a repository of lost histories and skills, bringing together thousands of accumulated years of knowledge and craftsmanship. And, in so doing, Closer refused the Wunderkammer binary that museum collections are regularly presented as. While, traditionally, these objects might have been displayed in vitrines, here they existed in the open air, without a barrier between them and the view.

Turnbull also built tables to house the collection objects. With their multi-coloured legs and semi-circle structure, they might have been twee on their own. But when in contact with the historical pieces, a strange sense of historical levelling out—an ahistoricity—took place; it was as though the history couched in terms of the artefact and the zero age of the contemporary platforms they were on cancelled each other out. No doubt, there was a utopian impulse that ran through Turnbull's exhibition. But I don't care if you think utopian is a dirty word; here I use it positively. While there maybe is no such thing as a world where objects are all given equal significance—where a simple wooden bowl is seen as just as valuable as a Roman jug—surely we can argue, at the very least, that one of art's functions is to clear the space for seeing things differently, even if, in the real world, that microcosm cannot materialise. This was the strength of Turnbull's exhibition: to use art to propose new ways of existence, as 'model' not as 'fact'. This, of course, is not dissimilar to the rhetoric of avantgarde artists, only here Turnbull looks back into the past to create her utopian vision.

Amelia is a Melbourne-based arts writer and PhD candidate in Art History at the University of Melbourne.

Zac Segbedzi and Friends (enemies) Early Career Group Show

West Space, Friday 5 July – 18 August 2018

By Giles Fielke

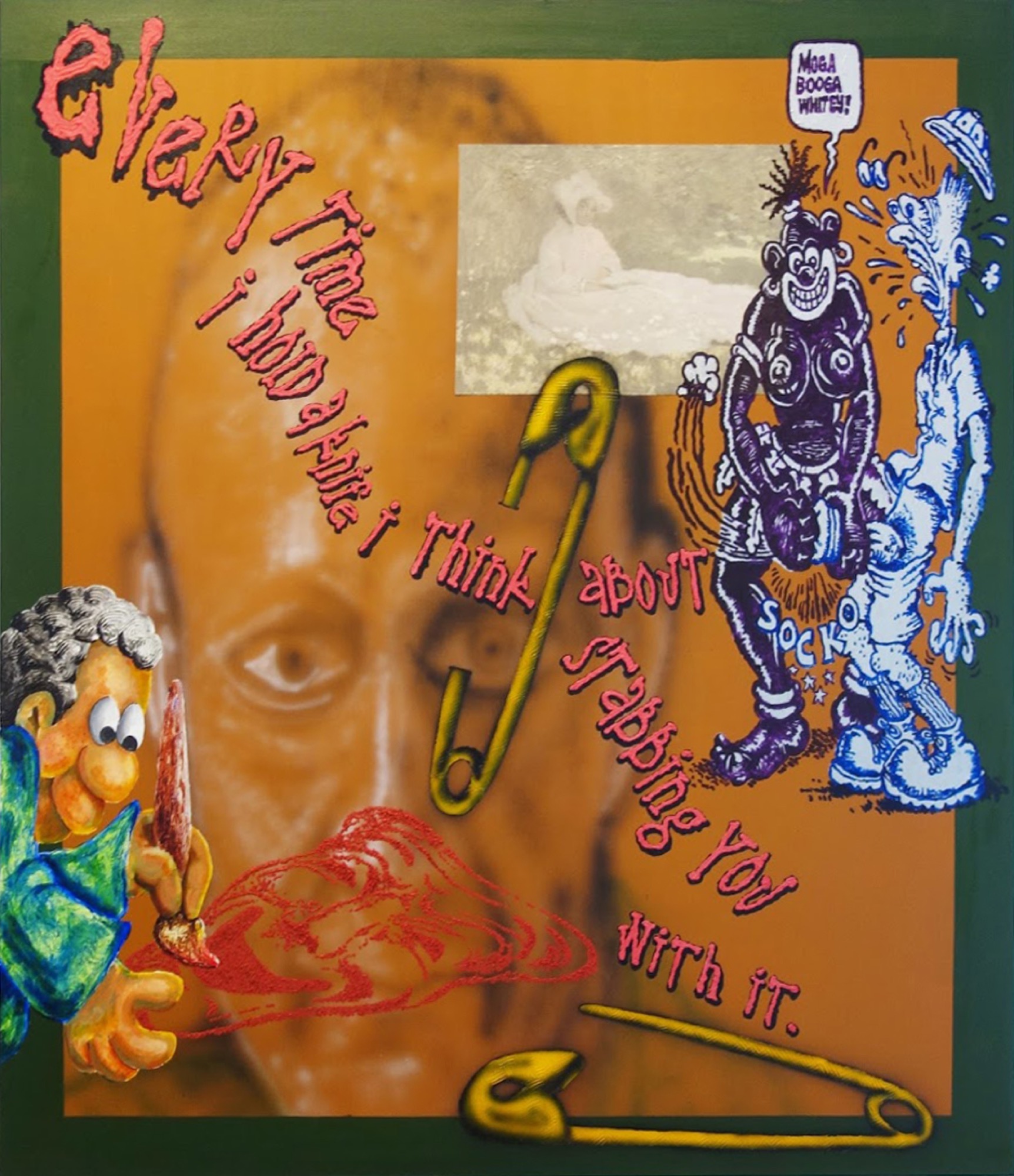

A black and white image of the contemporary pianist Javier Perianes, a photograph of a cute miniature donkey on Instagram, and a punctuation mark are the promotional material given for a retrospective hybrid solo/group show of work by Zac Segbedzi, titled Early Career Group Show. This is all that appeared before the exhibition opened at West Space, at which time a real miniature pony (apparently toy donkeys don't live around here) arrived with the artist in the gallery, accompanied by hired piano muzak. A digital flyer for the show was also circulated online, made up of parodies of conversations adapted from local commentary on the contemporary art scene in Melbourne: the police, arts administration, theory of exhausted narratives, etc. This is Segbedzi's artistic gambit, one could call it a self-conscious performance of the online troll—usually encountered as a 4chan Incel/Cuck, a confused and/or sick teenaged boy—assimilated to a particular subjectivity as the model of the contemporary artist. The works by Segbedzi, and his friends (enemies), conspicuously installed and mostly wall-mounted paintings, are not uninteresting to encounter in this space, however. Seeing past the defensively “Punk” façade, they become the grotesque results of modernism's forcible mashing together of art and life, a negative Frankenstein. Alt-art that feels very 2018—not just painting and installation, a performance.

The idea of a systematic program for the atrophied breeding of an animal-slave, to the status of lap-dog pet (the small donkey/pony) actualises the sentiment that Segbedzi seems to hold towards the contemporary arts in Australia and in particular Melbourne's inner-west. Stranded on islands in the Mediterranean basin, the animals became tiny. This gesture towards isolated purity is mirrored, perhaps, by the gridded paintings he made and first showed in series at Monash University's MADA studios last year. The (literally) hidden centre of the show, large and calmly offensive swastikas painted on cotton duck within the grid format are included in the retrospective under paper wrapping (censored by the gallery, not the artist; the text makes sure to make the point), suggest a niche scene that takes its references from the bad boys of contemporary painting: some older—Michael Krebber or Merlin Carpenter—or current “stars” like Mathieu Malouf and Jordan Wolfson, or even Chief Keef's Glo Gang enterprising from Chicago drill music to the LA gallery scene. (I also think of Dean Blunt's contemporary art debut, featuring only freshly delivered McDonalds while a siren played on loop in the downtown LA art space.)

Other than the glut of large and cumbersome works by Segbedzi in the show, works by artists (in no particular order) Katherine Botton, Liam Osborne, Grace Anderson, Natasha Havir Smith, Calum Lockey, Hana Earles, as well as a wall-text biography of far-right German AfD politician Alice Weidel, which seems to credit her as an artist in the show, serve to create a sense of coherence and aesthetic style identifiable as specific to a select community of artists working in dialogue as contemporaries.

In Chris Kraus' description of the figurative painter R.B. Kitaj, she seeks to plot out an alternative reality where his work is key to the arts discourse of the 20th century, rather than peripheral to its central, modernist narrative—an interesting idea occurs that seems both to negate the canon as well as attempt to lionise Kitaj's brilliance: 'Curatorial excitement mixed with apprehension: how to make this “difficult” work accessible? By introducing us to the artist as an admirable freak.' Segbedzi and co.'s works are so deliberately freakish in that they all require their own 'spray-painted' didactics—engineered as an exercise in art-jargon by the artist and written by students. Often entire canvasses of painted text are stapled to, or feature alongside, the variously painted works to further 'explain' them to a presumably perplexed public.

West Space director Patrice Sharkey has been bold in offering Segbedzi the show given the current climate of misogyny in Melbourne and the #MeToo moment more generally. Segbedzi's attempt to cut the success of artist Minna Gilligan down to size through the unauthorized exhibition of some of her student drawings, which he showed at White Cuberd, a portable gallery he ran through 2017, was mostly met with consternation. In all, the show seemed designed purely to injure the artist emotionally, but was masked as a critique of the commercial art world and in particular Gilligan's gallerist Daine Singer. At West Space the results of six years of post art-school work still teeters on appearing only as a massive “art-world” in-joke, albeit in miniature. A storm in a teacup. West Space's public galleries allow us to glimpse the private lives of a tiny scene of art-school graduates, as competitive and brutish as they come. The work, therefore, falls by the wayside: this is about the lives of the artists.

There is no doubt that there is something compelling about a painter whose work could convince Scarlett Johansson's boyfriend to fly in to Melbourne for an afternoon while hanging out on set in New Zealand, just to buy a Segbedzi painting spotted on Instagram to take back home to LA. Is it this fetishisation of the bad boy lifestyle's seemingly limitless resilience that makes Segbedzi an interesting artist, however? Or is it his personal demons, incessantly mined for public content, or is it simply his unmistakable skill as a painter and conceptualist? “Grandpa died in the Holocaust and Daddy abandoned me at birth” is one phrase in the text-heavy show, painted and just visible over a monotone representation of Adolf Hitler. It turns out his father is a billionaire property developer. In another painting his father's portrait appears menacingly, juxtaposed behind a melange of violent yet comical imagery.

Segbedzi is leaving Australia to study in the US. Instead of seeking infamy, it appears he’d rather just be an artist. The artist as a troll (is Shrek the reference here?) is a position that Segbedzi occupies all too easily, but not without the difficulty of knowing that self-deprecation is ultimately limiting. Aim small, miss small. “The failure to prize the chance to spend time in a cosmopolitan city highly enough to refrain from giving it up in favour of an upstart one-horse town,” wrote Robert Walser, before his face-down collapse in the snow, into obscurity, belies the fact that in the provinces the one-trick pony evolves over time, becoming something altogether different from what it once was in the big-smoke of history. The toy “donkey” (i.e., the Shetland pony) may be a freak of biological determinism, but it is a beautiful one.

Giles is a writer and musician working at Monash University and the University of Melbourne. He is the Business Manager of the AAANZ.

Title image: Meredith Turnbull, Closer 2018, installation view, Ian Potter Museum of Art, the University of Melbourne. Photographer: Christian Capurro.)