Language Exchange

Anastasia Murney

In the plantation colonies of the Americas, monocrops went hand in hand with monolingualism. The goal was to create standardised conditions in order to ensure predictable outcomes and massive profits. For the ruling colonial power, interlingual communication was a contaminant and a threat to the regimented structures of the plantation. According to Haitian anthropologist Michel Rolph-Troulliot, the formation of Creole languages was a miracle that was not supposed to happen. In their “free” time, slaves would cultivate their own gardens at the edges of the plantation, talking across fences, mourning their loved ones, learning new songs to work to, caring for neighbours, and teaching children. These were illicit acts of cross-cultural communication that subverted the rigid social world.

The plantation model exemplifies how the ascent of a single language to a dominant status is never an innocent or accidental phenomenon. Currently, no language has reached the scale and influence of English. And in its wake, English leaves mangled, marginalised, and extinct languages. In the 1980s, there was an intensive push to establish English as a global lingua franca. For instance, Sir Richard Francis stated in a 1989 British Council Report: “Britain’s real black gold is not the North Sea oil but the English language. It has long been the root of our culture and now is fast becoming the global language of business and information. The challenge facing us is to exploit it to the full.” English is therefore another crop to be exported, to saturate global markets and squeeze out local products. The British Council Report makes explicit the real material conditions underpinning linguistic imperialism. Colonial languages don’t just describe resource extraction and commodification: they operationalise it.

Language Exchange, a group exhibition curated by Amy Prcevich, at Fairfield City Museum & Gallery (FCMG), asks how are we to give weight to multiple linguistic worlds while contending with the dominance of English in settler-colonial Australia. The City of Fairfield is one of the most multicultural regions in Sydney. As of 2021, 69.7% of people used a language other than English at home. The meagre phrase “other than English” conceals over 130 different national groups. In the aftermath of the Second World War, European migrants flocked to Fairfield. In the 1970s, a large number of Vietnamese migrants moved into the area, meeting racism and xenophobia from the first wave. In the decades since, Fairfield has welcomed humanitarian arrivals from Iraq, Lebanon, and Syria. Of course, during all of this, Fairfield was (and remains) the unceded land of the Cabrogal people of the Dharug Nation. So, Fairfield is a fitting context for this exhibition: its diverse composition is suggestive of what Australia could look like without—or against—the monolingual container of the nation-state.

The title of the exhibition, language exchange, suggests a mutual and equal understanding. You might offer or receive meaning from another person. Alternatively, an exchange can be a transaction. You might give something in order to get something. However, the exchange might not be a fair trade. It could conceal unequal power relations: you lose something in order to become more palatable, legible, governable. Once again, language can be thought in terms of economics, begging the question: what is the price of entry into a dominant language system such as English?

Language Exchange feels small even though it features the work of eleven artists. Their work is hung in a narrow gallery space, but somehow the exhibition doesn’t feel crammed. Perhaps this is due to the differences in scale and perspectival shifts from artwork to artwork. Some are large and didactic; others are lightweight, modest, and cryptic. On entering the exhibition, Jannawi Dance Clan’s Dyalgala (embrace) (2024) is a welcoming arrangement of paper bark and reeds bundled into branches and annotated with colourful Dharug words.

Just across from this is James Nguyen and Nguyễn Thị Kim Nhung’s Vietnamese Acknowledgement of Country (2017), requiring close attention. It consists of two pieces of paper filled with pencil handwriting, fusing broken English with broken Vietnamese. The result is something that sidesteps “standard” English altogether, striving to express the cultural specificities of living on stolen land.

Up the back of the exhibition is Rachel Schenberg’s comically small on or in (2024), a video diptych comprising two miniature boxes with scrolling white text on red and blue backgrounds. It takes a few moments to settle into the rhythm of the scroll, punctuated with exclamation points, arrows, and slashes. The experience of moving through the exhibition is productively disorienting. Most of the artists express the alienation of speaking in language that has erased or diluted their ancestral tongue, like being forced into a costume that does not quite fit. At the same time, there is a sense of sculptural desire rippling through the exhibition, moulding alternative propositions for what language can be.

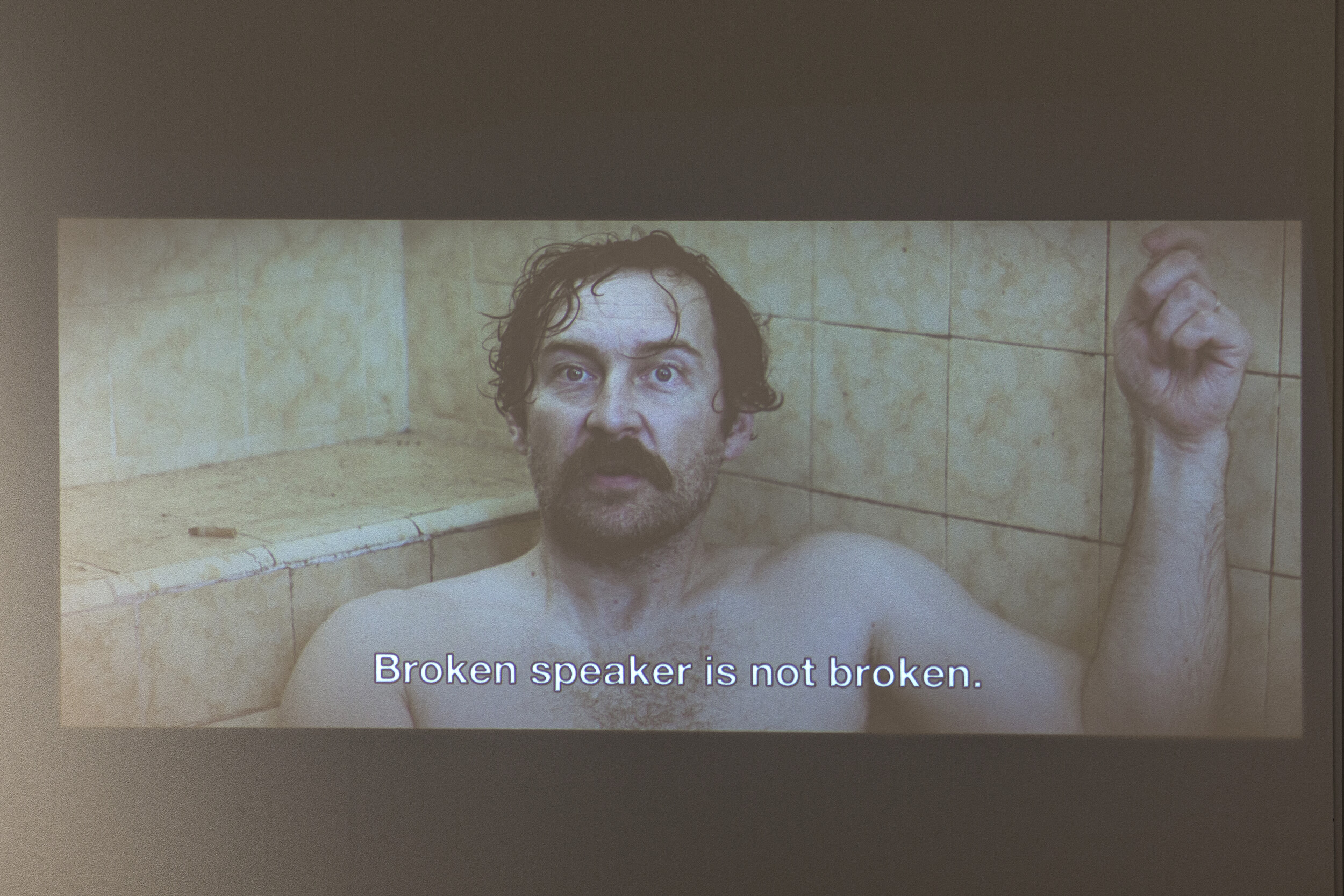

Kuba Dorabialski’s Broken English is My Mother Tongue (2020) echoes into the middle of the space. In this nine-minute film, Dorabialski soaks in a bathtub and speaks to camera while gesturing with a cigarette. A piano soundtrack chirps playfully and idiosyncratically as he speaks. Dorabialski interrogates the idea of “broken” English, leveraged as a slur, indicating something deficient or deviant. This is similar to how the “non” in “non-native English speaker” suggests a sense of lack. When Dorabialski mentions his mother, the film cuts to a little red sports car speeding along a highway. A woman (credited as “assassin mother”) disembarks and lines up a perfect shot of Dorabialski walking barefoot along a beach. I laughed out loud in the part where he is shot with a poison dart. The assassination is the violent “break” between English and Polish. Dorabialski resolves to speak in the space of compromise, a space between languages that is full of creative potential: it is flexible, unfinished, accommodating. For him, speaking both at the same time is to speak in multiple dimensions.

Opposite, Anne-Louise Dadak’s Zwischen (part 2) (2024) fleshes out the formal dimensions of language. I stand in front of this artwork not knowing where to begin. It looks like an experimental alphabet on swirling pastel sheets of paper. The rows of paper are printed with curious geometric shapes. On a shelf below is an assortment of intimate objects, positioned like archaeological clues to unlock this mysterious script. Similar to Dorabialski’s idea of compromise, Dadak is interested in the spaces between languages, coalescing her personal experiences with English, German, and Czech. There is something secretive about these artworks that reminds me of the conspiratorial origins of Creole, forming on the margins of the plantation—experimental words and phrases rubbing against the grain of monolingual imperatives.

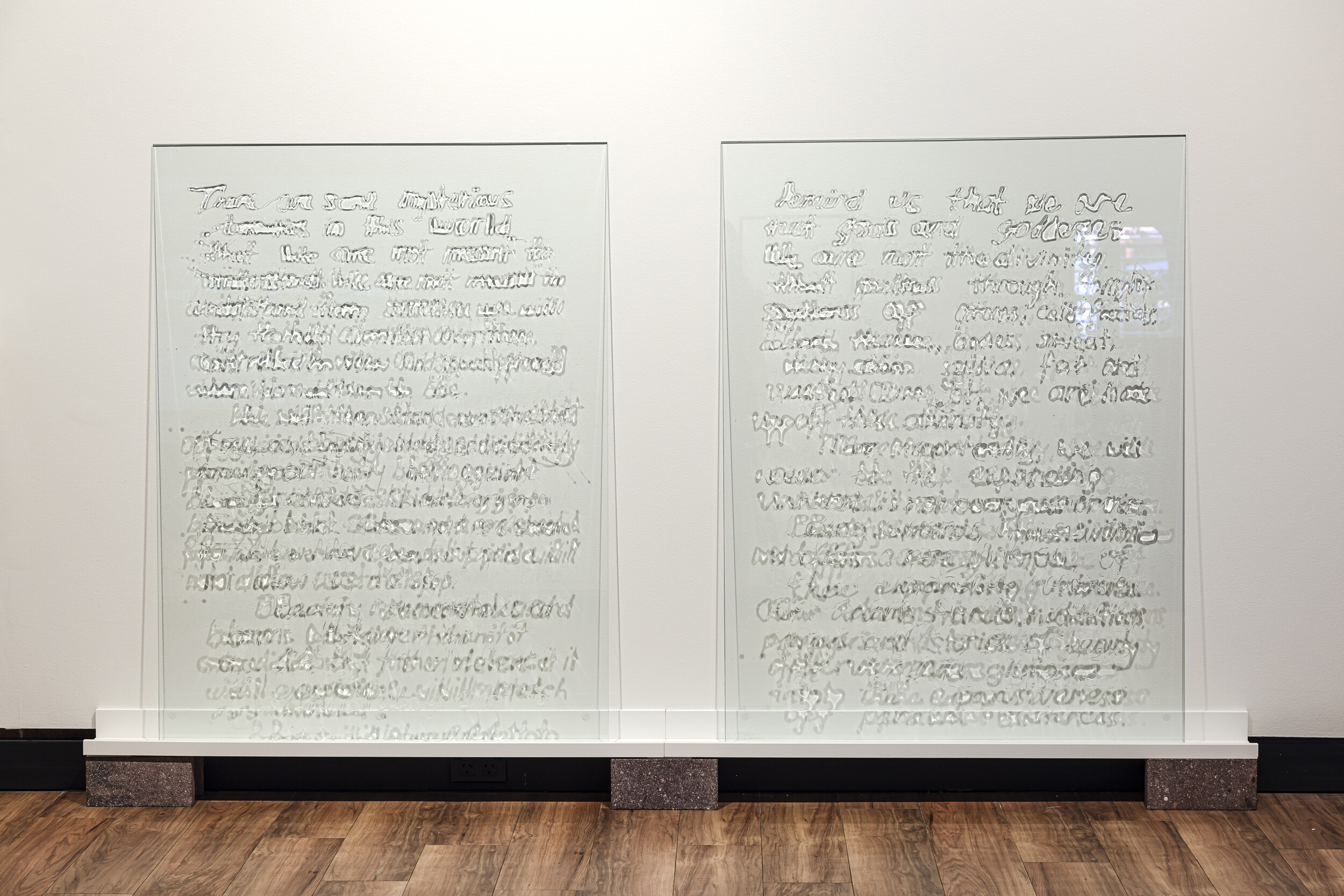

Audrey Newton’s neighbouring work, The Shape of Words (2024), makes this clandestine impulse even more explicit. Two clear panes of glass rest against the wall, engraved with a handwritten letter. I move back and forth attempting to find the right angle to make the letter legible. Do I read the engraving on the glass or the shadow of the writing on the wall? I manage to decipher single words: goddess, skin, and blank. Newton’s work includes a pile of envelopes ambiguously addressed “to us.” I take one and slot it in my bag.

The bitter truth is that pidgin and Creole languages are often forged under conditions of colonial occupation. This makes them contentious: the emergence of Creole as a functional linguistic amalgamation is tied to the loss of traditional Indigenous languages. Jazz Money’s work abandon to begin (2024) makes this tension apparent. A looping fourteen-minute video sees the artist standing in front of a chalkboard, erasing white text written on the black surface. In her statement, Money reflects on the unbridgeable gap between English and Wiradjuri: to speak English takes her further from Wiradjuri, a language that does not operate according to the same possessive and instrumentalist logics. In this work, the compromise is too great. English is too corrosive, hence it must be abandoned to begin again. As the video unfolds, there’s never quite enough time to read Money’s handwritten text in full. Watching the words being swallowed up functions as an exercise in deschooling, reversing the dissemination of English. One short phrase that stands out is: “all that cannot be contained in English.” Yet, Money’s work is contained in English. In this sense, translation into English is the price of admission into the art world. English is how to survive in the Anglosphere. Its power is pervasive but not total: it can still be used as tool for subversion.

Schooling is a significant theme that reverberates through Language Exchange. In addition to Money’s gesture towards deschooling, Dorabialski speaks of the shame he felt on learning he was, in fact, not good at English as a child. In a similar vein, Southwest Sydney rapper L-FRESH The LION’s Mother Tongue (2020) is a music video narrating his loss and attempts to recover his mother tongue, Punjabi. The video features a biographical sequence of photographs: scenes from India, portraits of his grandmother, a young L-FRESH standing on a podium and attending his first day of school. He raps about how school coincides with the pressure to conform. Schooling, in Australia, and in its more ruthless forms, is a critical point of rupture and a major instrument for enshrining monolingualism, framing multilingualism as something to be shed in order to progress.

In the back corner of the exhibition, Marian Abboud’s collaboration with Think + Do Tank, To Love and be Loved… I Will Live To Tell (2024) participates in this conversation about schooling, but it offers a reparative pedagogical approach. The space is hung with gauze curtains and strips of paper printed with fragments of poems and photographs. Think + Do Tank is a multilingual arts organisation that has contributed a selection of children’s books in different languages. Visitors are invited to sit down and weave the fragments into their own experimental compositions. Abboud takes inspiration from the writings of Gazan poet Dr Refaat Alareer and philosopher Muhyiddin Ibn Arabi. Alareer’s poem “If I Must Die” went viral in late 2023. On December 7, he was murdered by an Israeli airstrike in northern Gaza. In the two weeks between attending Language Exchange and sitting down to write this review, Alareer’s daughter, to whom the poem was addressed, has also been murdered, along with her husband and newborn baby. Abboud’s work reminds me of another Palestinian poem that has been recirculating in recent months, Rafeef Ziadeh’s “We Teach Life, Sir!” from 2011. This poem opens with the line: “Today, my body was a TV’d massacre that had to fit into sound bites and word limits.” This is what I think of when I sift through the little pieces of paper. Abboud’s work, however, does not reproduce the mediatised violence of abstraction. It is closer to the tender dressing of wounds (gauze, as a material, comes from the silk weavers of Gaza). The act of stitching and hanging these compositions feels like a fulfilment of Alareer’s last request: to fly kites and remember him.

I forget about Newton’s envelope until a few days after attending the exhibition. I pause as I start to rip the seal. The uncomfortable experience of straining to understand is something I would like to hold onto, to remain adrift in the space of not quite knowing. Inside, I find the handwritten letter, rendered legible as ink on paper. Reflecting on Language Exchange, I think of the Martinican philosopher Édouard Glissant and his call for opacity as a form of decolonial refusal: to refuse the transformation into categorisable objects of Western knowledge, to refuse to be made legible and therefore conquerable. Most of the artworks in this exhibition do not yield easily to interpretation, nor should they: they remain, to a certain extent, opaque. To squint and strain while attempting to read letters in engraved glass, or faint traces of writing on a chalkboard, or an unfamiliar alphabet, is one small step towards relinquishing monoglot privileges in so-called Australia.

Audrey Newton, The Shape of Words, 2024. Photo: Document Photography

Anastasia Murney is a writer and teacher living on Gadigal land. She holds a PhD from the University of New South Wales.