Public artworks don’t typically get written about unless they’re associated with controversy or celebrity. The Keith Haring mural on the wall of the old Collingwood Technical School overlooking Johnston St has plenty of both and, as a result, far more than its fair share of commentary. It was originally painted in 1984 during Haring’s month-long trip to Australia, at the height of his fame and only six years before his tragic death in the HIV/AIDS epidemic. By 2010, the deterioration of the mural led to a concerted effort to restore it. Bec Peniston-Bird’s 2015 documentary about the conservation project, Keith Haring Uncovered, narrates the ensuing drama as warring factions of conservators, curators and heritage experts debated how best to save the mural. There’s also a wonderful sub-plot involving the theft of part of the mural, recounted first-hand by the thief himself, who appears on screen as an anonymous darkened silhouette. Haring had signed his mural on a small wooden access door, attached by hinges to the bottom of the wall. The next part of the story is entirely predictable. At some point in 1990 this enterprising individual, who for reasons unknown was carrying a screwdriver on his way home from a gig at the Tote, “rescued” Haring’s signature by loading it into the boot of his car.

The documentary’s story arc is a wonderfully satisfying dialectic. Seemingly antithetical philosophies of conservation (do you conserve and protect the artwork itself, or do you repaint the work, restoring it to its original vibrancy and thereby conserving the artist’s original vision?) are happily resolved when conservator Antonio Rava points out that removing the calcification on the surface of the paint will do both. Everyone is pleased that this important Melbourne landmark has been saved. Even the thief is pleased, and obligingly returns the signature door, which the conservators triumphantly reinstate. Anita Smith from the Heritage Council of Victoria notes, correctly, that there is an enormous amount of respect for the mural in the community. Melbourne street artist Adrian Doyle talks about Haring’s work as an inspiration, creating an implicit genealogy linking the mural to the 1990s rejuvenation of Melbourne’s laneways. Phil Pereira, a former student at Collingwood Tech, comments: “If the Keith Haring still exists on that wall, then I think Collingwood Tech still exists, you know?”

So—job done, right? Why say more about it? Well, I was struck by that last comment. In what form, and to what ends does Collingwood Tech still exist? If the Haring mural does stand in for that chapter in Collingwood’s history, what meaning does it have now, and what purposes does it serve? It seems to me that not only the conservation of the Haring mural but also the original circumstances of its creation are a case study in the intimate relationship of cultural and commercial value, and the extent to which both of these value systems these days feed off a single magic ingredient: poverty, or – more precisely—the aura of subversive glamour that can be profitably spun around gritty, “authentic” disenfranchisement.

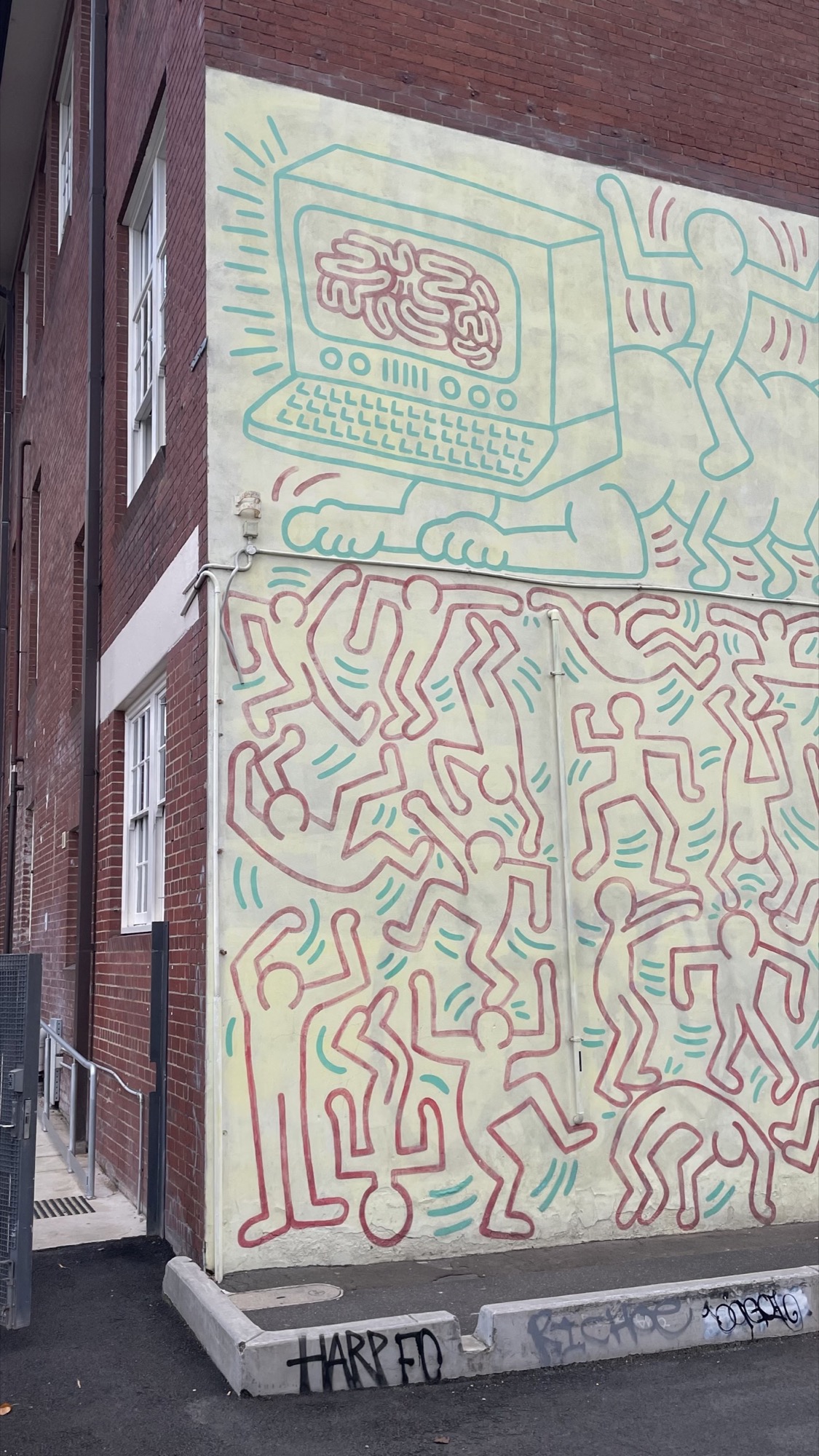

The mural has a kind of “power to the people” energy. A teeming, gravity-defying mass of bodies dance, brawl and twitch across the lower half of the wall. They are packed in, horror vacui-style. Haring’s improvisational linework was famously done without preparatory drawings, he worked responsively, constantly adjusting his composition to his working surface to fill the available space. You can see how he’s arranged the figures in joking conversation with the water pipes that run across the wall—one figure on the left of the composition seems to balance a vertical pipe on their foot, another in the centre dives forward underneath a ventilation grill. Across the top of the work, a monstrous computer-headed caterpillar stands in enigmatic relation to the people below. The clear division between the upper part of the mural and the crowd of smaller, red-painted figures seems designed as a political allegory, but one that remains purposefully ambiguous. Possibly representing Orwellian top-down political authority—the work was painted in 1984, after all—the creature could also perhaps be a manifestation of the popular will, a golden calf held aloft by the masses.

Haring’s high-energy graphic style has its mythic origins in New York street art. Writers discussing his work almost invariably focus less on his training at, first, the Ivy School of Professional Art in Pittsburgh and then the School of Visual Arts in New York, and more on the drawings he made in New York’s subway system. From around 1980, Haring created ephemeral chalk drawings on the blank surfaces of vacant advertising space, making the subway his studio and turning the practice of drawing into a performance. He chose to work during the day when the subway was busy because he enjoyed the conversations with passers-by. In addition to identifying the public orientation of Haring’s practice, writers also typically mention his association with more “authentic” (read: untrained, non-white) street artists like the teenaged Puerto Rican graffiti artist Angel Ortiz, aka LA II, with whom Haring collaborated through the early 80s. As performance scholar Ricardo Montez observes in his recent book, Keith Haring’s Line: Race and the Performance of Desire:

By both artists’ accounts, Haring’s and LA II’s collaboration was mutually beneficial and enriching. But these men produced their work in an economy of authenticity and prestige that fundamentally inflected how their coproduction was perceived. The younger artist became a key signifier for arts writers and consumers interested in Haring’s connection to hip-hop communities … The young, often shirtless brown subject at Haring’s side functioned as a fetish object for an art market invested in the aura of the street.

After the first wave of institutional critique peaked in the 70s, artists needed to earn their social legitimacy by means other than institutional sanction. Punk and hip hop demonstrated the power of grassroots credibility: a sufficiently gritty origin story could act as armour against the stench of the establishment. Artists who successfully demonstrated that the institutionalised art scene was not their natural habitat were—paradoxically—granted a license to flourish there with impunity. Jean-Michel Basquiat is a great example. Haring’s queerness, his street-art affiliations, his interest in unscripted public engagement and his friendship with artists like LA II and Basquiat all contributed to his alternative credentials, an aura of authenticity that translated easily into both institutional approval and commercial viability. It makes complete sense, then, that the organisers of Haring’s visit to Melbourne arranged for him to create a public mural at Collingwood Tech.

The swampy area of Wurundjeri land around what is now Hoddle Street was known by settlers in the nineteenth century as the “Collingwood Flat”. In the early days of the colony, it apparently regularly flooded with stormwater and sewerage overflow. Relatively slow to be settled, the Flat was primarily a working-class and industrial area into the twentieth century. Local industry tended towards the environmentally noxious kind: abattoirs, wool washers, tanneries, breweries. Collingwood Technical School opened in 1912 to deliver practical education to local boys, preparing them for trades and apprenticeships. By the 80s, however, the school was on its last legs with a dwindling roll of students. Part of the school was separated off to form a new Collingwood TAFE in 1981, and the remaining Year 7 to 10 classes struggled to survive on greatly reduced resources, eventually closing in 1987. When Haring arrived in 1984, he was affable and generous with the students, who were entranced by his fame, his New York cool, and the fact that he played rap music from a customised boom box while he painted. The CTS newsletter reported: “I think it’s fair to say that we all loved having him here, and that he has done a lot for the school. There was always a group of kids and teachers out there watching him, talking to him, asking him about everything from his psychedelic cassette player to what it was like living in America”. The positive feeling was mutual. Haring told them, “I had fun. I mean, it’s the most fun I’ve had since I’ve been here. It’s more fun working here than it is inside a museum”.

The recent conversion of Collingwood Tech into the Collingwood Yards art precinct is, as Giles Fielke has pointed out, a cherry on top of the rapidly unfolding and extreme gentrification of this area. Collingwood’s industrial history has now become extremely expensive, if not yet technically priceless, in the form of chic inner-suburbs apartments. For example, currently for sale in Collingwood: a 3-bedroom penthouse apartment in the 1876 Yorkshire Brewery building, featuring exposed decorative brickwork and double-height ceilings, for a cool $2.95 million. Today this authentic industrial history comes at a premium in the property market. Collingwood’s transformation from a rough part of town to a property developer’s paradise began around the time of Haring’s visit. The Age reported in March this year that ANZ economists expect Melbourne house prices to rise by 16% in 2021, and that this would constitute the fastest rate of growth since the property boom of the late 1980s.

It’s possible to track a similar development in the CBD. Melbourne’s laneways were created so CBD landowners could more easily access their properties, but also so they could more easily subdivide them. During the gold rush, soaring land prices led directly to increased subdivision and the creation of more laneways, which provided access to cramped accommodation for working class people, recent migrants and small manufacturers. At some point during the 1990s, the magic fairy dust of gentrification transformed the graffiti and overflowing rubbish bins from an eyesore into the kind of gritty authenticity that can support a flourishing urban café culture and wedding photo industry. The City of Melbourne’s Laneway Commissions scheme, launched in 2001, invited artists to produce temporary public artworks in the laneways. The Laneway Music Festival, launched in 2005, also capitalised on and fed back into this emergent urban laneway culture and the businesses it supports. Laneways—particularly the ones that retain visible evidence of their working-class and industrial origins—are increasingly being granted heritage protections.

It’s easy to be cynical about the extent to which cultural and commercial value support each other, but I’m not arguing here that art is somehow desecrated by its association with business. Art, money and power have always been closely entwined. Nor am I suggesting that Haring simply exploited the CTS students, or LA II, in order to boost his street cred. Haring obviously had considerable marketing savvy, but so did ACCA’s inaugural director John Buckley and CTS teacher Ray Collier, who set up his visit to the school, and so too did LA II. These relationships and encounters were mutually beneficial, as Ricardo Montez observed, and Haring’s visit to Collingwood Tech was clearly genuinely significant for the students who got to meet him and see him work. What I’m more interested in is the way cultural narratives about value swirl around these encounters, informing how we understand them in retrospect but also influencing the way they play out in real time. Haring was welcome at Collingwood Tech because he was a famous international artist, but also—and particularly—because of the “street culture” aura that he had cultivated around himself and his practice.

The archaeological recovery of the Haring mural’s original paint surface by conservators in 2013 is satisfying because it feels like the recovery of a lost past, a true original. Having removed the calcification of years of neglect, we can feel proud that we are now truly respecting not only the mural but also the history of this site. Even the slightly faded quality that the mural now has—the colours are brighter than before, but not as bright as they were originally—adds to this patina of history. The installation of the art precinct at Collingwood Yards is similarly redemptive. The sensitive re-purposing of Collingwood Tech’s historic architecture symbolically undoes the violence of gentrification, showcasing a more respectful attitude in urban planning in which the stratified history of a site is acknowledged and preserved as a kind of palimpsest. The re-purposing of Collingwood Tech as an arts precinct—The Collingwood Yards—also, of course, serves to further inflate local property prices, perpetuating the ongoing violence of gentrification in exactly the same way that Haring did when he painted the mural in the first place. So in one sense, if Collingwood Tech still exists, it’s as added value in an already bloated property market, actual poverty converted into safely aestheticised urban texture. In another sense, if Collingwood Tech still exists, it does so because Haring’s practice was so deeply responsive. He didn’t only respond to the physical surface that he was working on, he fed on the energy of the people who were around him while he worked. In that sense, the energy brought to him by the school’s staff and students is encoded in the dancing, fighting bodies who remain up on the wall.

Anna Parlane is a lecturer in art history and theory at Monash University.