Improvements and Reproductions

Giles Fielke

The New Spirit of Socialism: “Improvements and Reproductions” at West Space

Powered by Lupa

It is the advertising that makes me pause. “Powered by Lupa” appears beneath every title announcement for the show. It makes me hesitate: how to read the phrase. Sponsorship? A reflexive re-appropriation of cultural capital? Lupa is an energy company, I presume. Maybe health insurance. Later I discover it is somewhere in-between, Lūpa is a media player created by artist Dara Gill, who was also director of Firstdraft gallery from 2010–12. West Space is now located in the Collingwood Arts Precinct; similarly, Firstdraft is part of the East Sydney creative precinct. I let it pass, this entrepreneurial spirit mirrors the new spirit of socialism. This was President Xi’s personal programme, added to the constitution at the 19th National Congress of the Communist Party of China in October 2017. What has this got to do with Melbourne’s art scene? Let’s see.

After almost opening on 20 March, the contributing artists of Improvements & Reproductions at West Space have had to wait until 18 June for the public to be allowed to visit the new(ish) galleries, where the now accessible work has been installed for nearly three months. Upon entering the galleries, the two distinct yet overlapping and complementary group exhibitions in the space become immediately intertwined. Originally programmed to run until 11 April, and co-curated by West Space director Amelia Wallin (Improvements) and 1856 organiser Nicholas Tammens (Reproductions), the shared curatorial conceit deploys the artworks in order to investigate—both collectively and separately—what they have called “the conditions under which art is produced”. That condition, given the shutdown and the accelerated collapse of our regular economies, now feels more difficult to define than is usually possible.

I decide to refer to this situation as “the state of conditions”. In the intervening months, between the almost-opening and the present re-opening, it feels as though these conditions have changed almost daily. Over-mediated, the aestheticisation of “new” labour (JobKeeper or Seeker, WFH, zero-hour contracts, the gig-economy) now has a simple device for this endless present: a plug-n-play black box repeater, Lūpa. At least one of the works in the show is using the device. Imagine Tim “The Toolman” Taylor’s Home Improvement crossed with Amalia Ulman’s Excellences & Perfections. This is Big Art Energy (BAE). Right now, nothing makes sense.

Wallin has commissioned new works by Rafaella McDonald, Georgia Rubenstone and Katie West (whose permanent installation, Untitled, is made of calico dyed with Wandoo Bark and hung as a functional divider in the gallery office). West is a self-described decolonial artist and descendant of the Yindjibarndi people. The work, the commission and the curation are explicitly political, and in the current environment of a defunded and divided arts sector and explicit racism around the country, on paper the work might read as overtly charged with dissent. But the work hangs in the office; it is weightless. It is a beautiful object for a beautiful space (masking a storeroom). How can we reconcile these two positions? Is beauty quiet and still? Is violence only ugly?

These new works appear alongside older works by Mark Smith and Ilana Harris-Babou. Smith’s ceramic text sculpture, Improvable (2019, courtesy of the artist and Arts Project Australia), further orients the show around production—the production of one’s own body perhaps. The gilded letters only reach halfway up their sides. They lean humbly against the wall. Harris-Babou’s is the only international artist in the exhibition, and her 4-minute video, a DIS-commissioned from 2018, Reparation Hardware, extends from her Larrie Gallery show in New York. Installed in the window of the new gallery and quite literally broadcasted through the architecture, using a speaker that parasitically attaches to and transforms its glass pane, the work performatively demonstrates the difficulty of pursuing a reformist agenda, by employing heavy irony. Slowly, the beginnings of some things cautiously identifiable as simply “new” work collapse back into the nightmare of history.

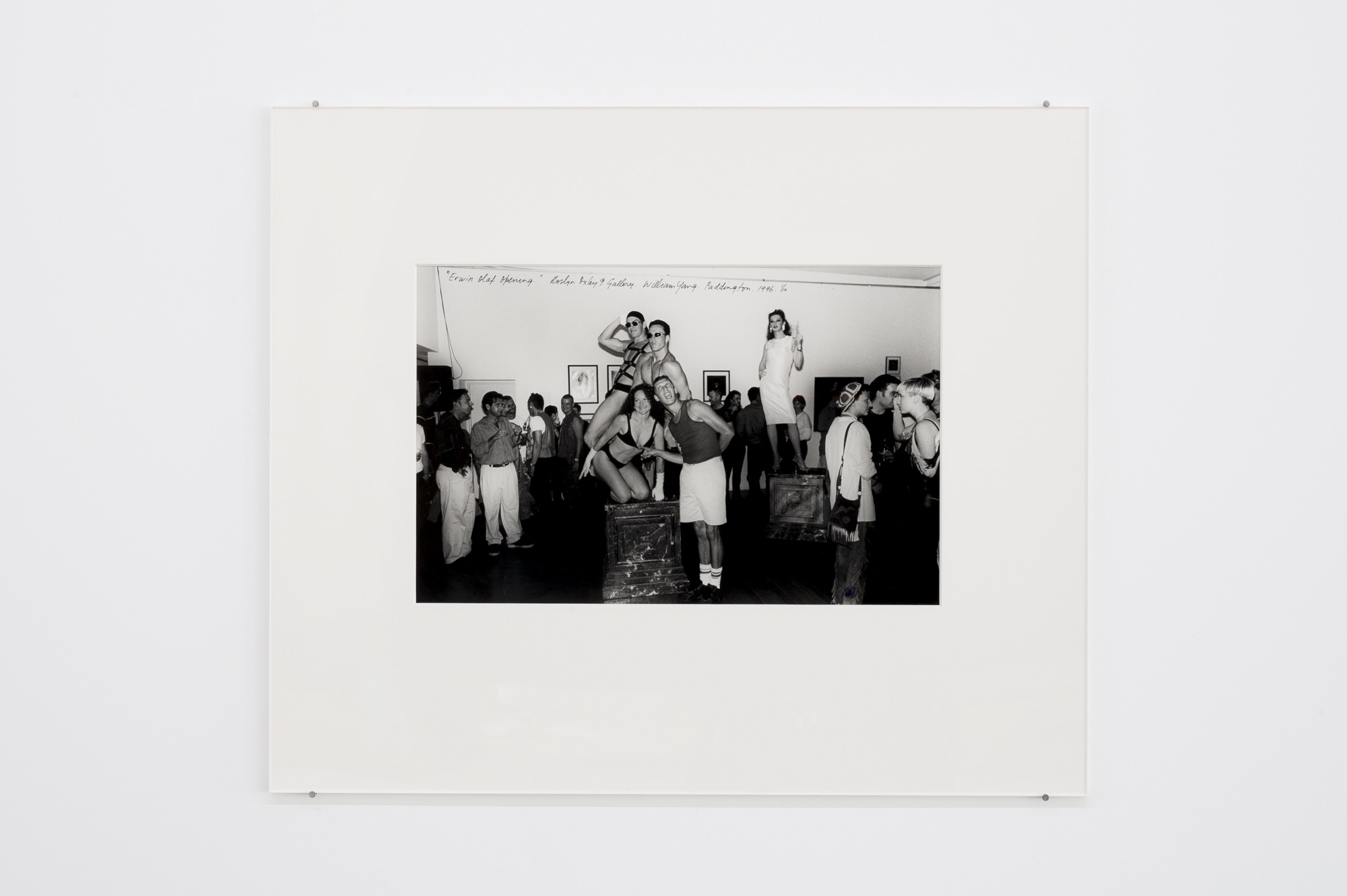

Similarly yet also alternatively, Tammens’ Reproductions curates new works by Isadora Vaughan (Resus as an organology of sugars, or just abandoned Kombucha), a striking found-material sculpture by Waradgerie artist Lorraine Connelly-Northey which dominates the northern wall, a dateless painting by Josey Kidd-Crowe (Debt Forgiveness, courtesy of the artist and Neon Parc), with the older video documentation project MeowTV (2018–2019, courtesy of Carmen Sibha-Keiso and Meow), and a suite of William Yang prints depicting gallery openings and queer party scenes from Sydney in the 1990s. At the centre of the exhibition is a show-within the show, Spencer Lai’s Moral inventory. It is here, amongst the dirty stacked pint glasses and the reeking bag of months-old oranges that I can begin to orient myself: reproducing the same codes can also create a fundament from which novel signifiers begin to re-emerge. A scummy and dirty fish tank (provided by Rex Veal—who is also attributed, along with Tammens, for the spatial and conceptual components of the work) appears like the fragile maquette of an abandoned building, which, like the Collingwood Art Precinct itself, awaits restoration by the State Government, or idle hands making heavy work.

Seen at a distance, this collision of form and intention sets up a complex network of interactions, the assembling and intersecting layers of the Collingwood location is recapitulated as a site of intense contestation. This makes Improvements & Reproductions a gesture of acknowledgement veering on the edge of apology from the newest inhabitants of this particularly charged patch of Narrm / Melbourne, while linking the East and West coasts of the country with contemporary Black and Civil Rights discourses from North America. That was before the global pandemic arrived and the subsequent shutdown took place. Following these events, and their effects, the work takes on a different, funereal ambience. It has laid here, disregarded and slowly decaying, while we reacted to the menace.

Outside the nearly finished precinct itself—rebranded from Collingwood Arts Precinct (CAP) to the decidedly more awkward Collingwood Yards—is at the easternmost edge of Melbourne’s Inner-North on Johnston Street. This means West Space is now found wedged between Licorice Pie Records, Hattie Molloy—your new favourite florist—and perennial live-music venue The Tote. Previously, it was located above a duty-free outlet in a former bank building on Bourke Street. The “Yards” have been almost, and just about becoming, Melbourne’s state-of-the-art location, a self-styled “charitable social enterprise” for the better part of a decade (one can only imagine how many corporate consultants’ children have been put through the private school system with their taxpayer-funded fees). This is not irrelevant to the West Space show, it provides further context while enframing the gallery that is now more east than west.

As a reverse-ghettoisation project, rehabilitating the site of the Collingwood Technical School—which opened in 1912, but dates back to 1871 as a site for settler-colonial art and design education in the area—was first locked in after a feasibility study by Arts Victoria in 2012 (now Creative Victoria). The founder of Renew Australia, a charitable project focussed on ‘anywhere empty’, Marcus Westbury, became the CEO of CAP in 2016. A century after it had opened and twenty-five years after Collingwood Tech was closed (Circus Oz has been resident there since 2013), the re-generation of such a significant site—the Keith Haring mural—meant the Yards is the end-point of centuries of gentrification. Now it is (nearly) ready to launch the new spirit for public culture™: a delicate eco-system of subsidised artist space that remains built on the commercial lability of the sector, and condescendingly requiring a charitable hand from big business.

Now managed as a non-profit social enterprise overseen by a board of directors and partnered by Creative Victoria and the Bank of Melbourne, anxieties about the conditions on the role art will be allowed to play abound. In 1945, the chief architect of the Victorian Public Works Department, Percy Everett, designed the celebrated façade of the building that faces Johnston Street (Everett was also responsible for the Russell Street Police Headquarters and numerous other modernist and art deco building project undertaken by the State). Today the integration of formerly public works with private interest perfectly encapsulates the model envisioned for the arts in Australia. At around the same time George Seelaf, an inspirational arts figure for the 1856 project, linked communism to community. Today it seems somewhat absurd that this legacy would be targeted by contemporary arts policies. Ring-fenced, it seems Art may only take place in locations approved by our financial managers. This is not true, of course. But it is my opinion that this endless prevarication on the “value of the arts” is to the detriment of the art that is shown here. The artists themselves are, of course, far better at adapting than many other workers. This makes me curious, if not hopeful, for what this new spirit might bring.

History, as always, is the key. John Wren’s Tote may be the inspiration for rebranding the site “Collingwood Yards” but it is Frank Hardy’s novel Power Without Glory (1950), about “Jackson Street, Carringbush” which was not only subject to court-ordered suppression by anti-communist actors at the time, but also offended the Labour party whose party offices were used by Seelaf to surreptitiously print the book. Revisiting Wren’s yards in Collingwood where an illegal parimutuel betting system was operated out the back of the shop at 148 on Johnston Street (now a mid-century art and design store, Gallery Midlandia) in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, seems apt. In fact Wren’s granddaughter, Gabrielle Pizzi, would open a gallery in Flinders Lane in 1987, pioneering the contemporary market for Western Desert Painting and Indigenous artists such as Emily Kame Kngwarreye in the 1990s, through a series of Venice Biennale pavilions: Pupunya Tula (1990), Metamorphosis (1997) and Beyond Myth (1999). That Collingwood belies this strange mix of inner-city intrigue, and which continues today (only late last year the speakeasy venue at number 220, One Year, was shut down by authorities), means that it is the history itself that is meant to soak into the work exhibited here. Otherwise too fresh, curation becomes a strategy for washing contemporary art with authenticity.

Georgia Robenstone’s commissioned video work, included as a part of Improvements, takes Hardy’s novel as its explicit reference point. Power Without Glory is a 5 minute and 47 second work mixing found footage with new footage produced by the artist and shown on a two-channel display (using the Lūpa device I am guessing). Addressing the “gentrification” of Collingwood, coffee culture and media hypnagogics, the work feels necessary but like a room sheet, or wall didactics. If we are asleep at the wheel, “drive it like you stole it” remains the underlying intent to the “value” of the country. There is an attempt here then, by the artists and by the curators, to make a larger argument about “the state of conditions” we must face in Australia today. Artistic freedom is dead.

The totaliser, or tote, is a system pioneered by engineer George Julius in Australia, which he managed to mechanically automate during Wren’s heyday (it’s the T in TAB). Julius first tried to sell his “Totalisater” as a voting machine to the Australian Federal Government in 1906. Failing that he instead adapted it as a bookie system for betting on horse-racing (an example of which can be found at the Museum of Computing History, located in Monash University’s Caulfield-campus Building B lobby). While Julius became the first president of the CSIRO in 1926, Wren left betting to become a legendary powerbroker in the Labour Party. The totaliser system couldn’t automate politics without the spirit of its actors.

These are the necessary conditions. Following the branch stacking scandal that has riven the Labour Party in the past week, I was thinking through this strange set of references, when I re-entered the exhibition on Thursday 18 June. As a time-capsule for the moment before the shutdown, transfixed by MeowTV, I was reminded of Joe Hockey performing as Fabrizio Corbera: Everything must change for everything to remain the same. This is the indistinction of Improvements & Reproductions, the loop. Like the Polly Pocket plastics and other trinkets in Lai’s Moral Inventory, these references lie scattered as the remnants of an endless party. Now everything appears as it would have, only it’s been stretched, and splayed out across 2020 like a piece of gum that narrows as it’s torn wider and wider apart.

*an earlier version of this review stated that Marcus Westbury became the inaugural CEO of CAP in 2012, this was incorrect.

Giles is a writer and researcher of film and media art histories.