In Costume

Audrey Schmidt

Held at the newly opened Mejia gallery on Tinning Street, Brunswick (located near Neon Parc), on November 1st, the In Costume label launch included garments by Melbourne-based Canadian designer Brendan Morris produced with artist, Spencer Lai. The business card-like invitation reflects the label itself. It features a red rubber stamp-like graphic of planet earth with a trucker’s cap perched on top and what looks like sewing needles and circular eyelets surrounding it. The stamp is patchy and variable across the different prints on the cards and garments at the show, with the text ‘IN COSTUME’ featured in a goofy, warped sans serif typeface.

At the launch, In Costume’s branding was immediately apparent on all items of clothing, reminiscent of Walter Van Beirendonck’s graphic labels that are often in rubbers or plastics and sewn on the outside of garments. Several t-shirts in the collection were screen printed with motorcycle engine blueprints and the number ‘2019’, distressed to look as though they had been used as a mechanic’s oil-rag. By dating the collection to a year that’s nearly over, In Costume diverged from the fashion industry custom of working one or two seasons ahead. ‘2019’ felt like a self-conscious time-capsule, evoking nostalgia for the present in an industry that trades on its ability to predict the future or the next ‘now.’

Entering Mejia, two cars were parked nose-to-nose at a diagonal across the room with smoking incense sticks jammed in their bonnet, window and door crevices like daisies jammed down the barrel of a gun. In the centre of the space, between the car’s noses, there was a small gap and a solitary light source: a low-hanging fixture that read as a street lamp, illuminating the hoods of the cars, covered in dozens of Uber-sized water bottles with their labels inverted and “In Costume” inconsistently scrawled across them in Sharpie. The effect was somewhere between the car scene in Matthew Barney’s Cremaster 3 (2002) and someone’s bong-den garage.

The setting might have felt like a car dealership if it was not for the fact that the cars in question were fairly pedestrian used sedans. It was an atmosphere that shared sensibilities with Maison Martin Margiela’s Spring/Summer 1992 runway held at the deserted Paris Metro Station in Saint-Martin with 1,600 beeswax candles lining the stairwell’s handrails—a ghostly ritual or séance. This Margiela collection and presentation was highly influential in its use of repurposed vintage materials and represented a significant remove from the traditional seating arrangements and glitz of the conventional fashion catwalk. In recent years, such an approach to exhibiting fashion, using non-models (or nodels) and repurposed materials in unconventional locales has been broadly adopted by Melbourne-based practitioners, of which Spencer and Brendan have always played a part. Spencer nodelled in Rare Candy’s I have become a sign to many (2015) runway at the Carlton Garden’s fountain and in the Hollywood Seven (2016) RMIT honours graduate showcase at the Parkville Motel, which also featured ten looks by non-honours student Brendan. Perhaps most aligned with this most recent collection, however, is Brendan’s last collection, also produced by Spencer, Toy Fossil: Class of ‘84 (2017), which was presented in the hallway and kitchen of the crusty old sharehouse Spencer and I used to live in.

As with Toy Fossil, Brendan’s newest collection and its presentation remains concerned with the preservation or petrification of remnants of time, place and personal style. Brendan tells me, “they never find a whole fossil, they only find a piece and build the picture from there.” Although Brendan has lived in Melbourne for the last nine years, he grew up in Calgary, Canada. In certain respects, his perspective is anthropological—dissecting the cultural meaning, norms and values of an artistic community he is both a part of and an outsider to. As with Margiela, this approach to making aims to mark the course of time, rendering a garment’s temporality and previous lives visible. The garment’s signalled lived-in-ness turns it into a document, artefact or fossil to be historicized and decoded. In this way, the collection also recalls Hussein Chalayan’s 1993 graduation collection, Tangent Flows, where the designer oxidised and buried his garments in a friend’s garden for months before exhuming, resurrecting and ritualising them for the runway.

The word ‘costume’ also implies historicity—it is clothing that is customary of a time and place. Archived, frozen in time, costume is worn to look like someone or something else that it isn’t. Costume jewellery is imitation precious stones and metals. With its ‘distressed’ aesthetic, In Costume entered the tricky territory upon which the fashion industry has often been accused of ‘poverty cosplay.’ John Galliano’s Haute Couture S/S2000 for Christian Dior was inspired by Paris’ homeless population. Vivienne Westwood’s Man A/W2010-11 collection saw the runway plastered with cardboard boxes and the models accessorised with plastic bags, shopping trolleys and rolled up foam sleeping mattresses; models’ faces and hair matted with white powder like frostbite. Marc Jacobs’ 1992 grunge-inspired collection got him fired from Perry Ellis.

However, the distressed aesthetic of In Costume does not embody this couture mainstay. There is not even certainty that the label will continue as such after this collection. In fact, while In Costume was advertised as a label launch, not much was really ‘launched’ per se. Like other Melbourne-based fashion studios such as H.B. Peace (Blake Barnes and Hugh Egan Westland), In Costume defies the fashion system conventions of a ‘label’ (and all it connotes). There are no plans to mass produce or apply couture price-tags to the samples shown at the launch. But the real difference is that Brendan’s sources are not like those of the pauper-chic collections described above. Brendan draws from the idiosyncratic personal styles of his own immediate social environment and many of the individuals that inspired the collection also comprised the audience at the launch.

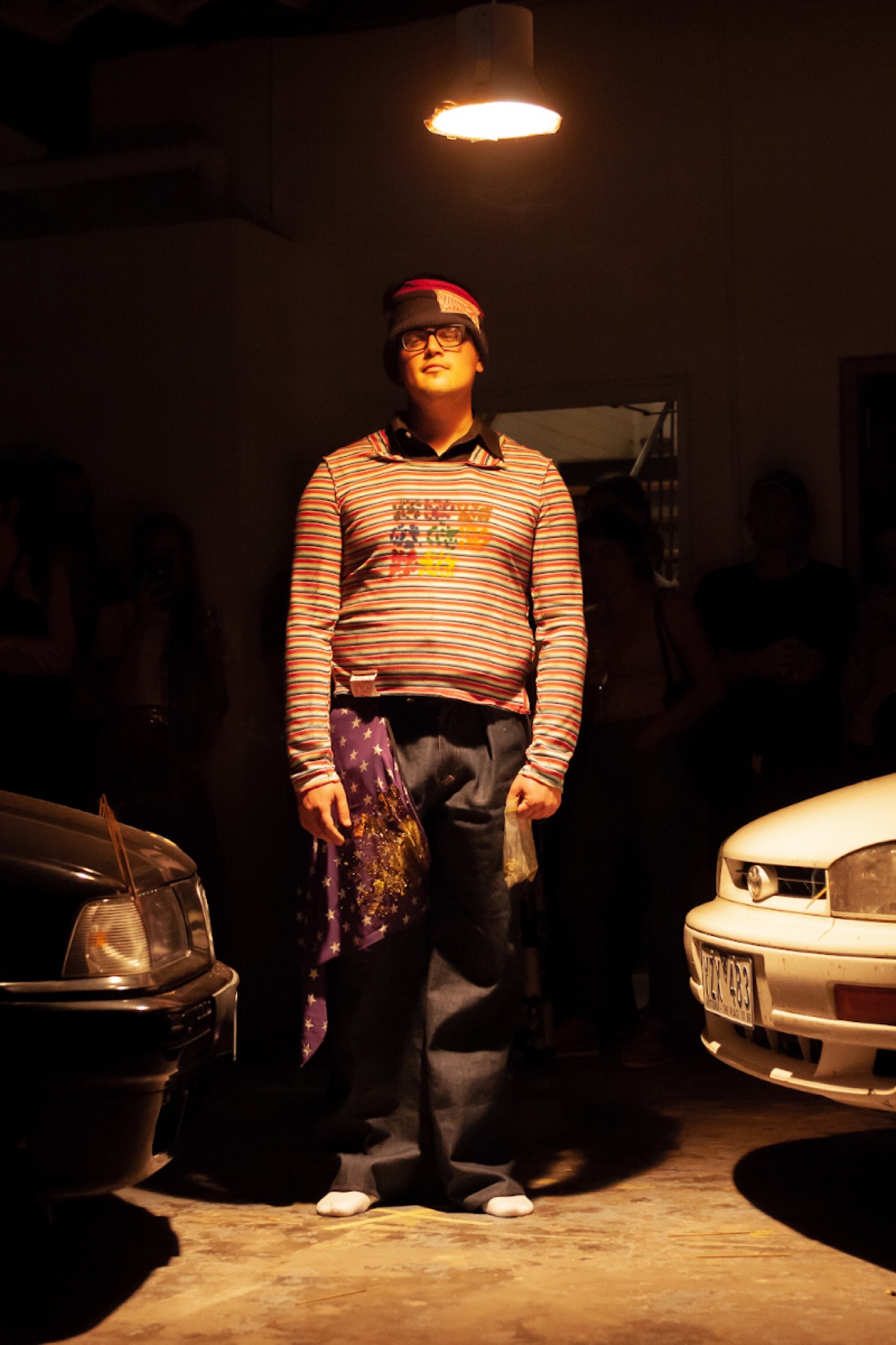

When the first look emerged from behind the black curtain that separated the studios from the gallery, John, who Brendan works with at Terra Madre (the more exclusive Whole Foods of Melbourne), was barely distinguishable from the crowd that had gathered in a circle around the cars. He wore a grunge-era printed t-shirt over a striped long sleeve shirt, a look that is described under Urban Dictionary’s top definition for ‘egirl’ in 2019. John’s frizzy blue-gradient hair perhaps amplified the connotations of this egirl appropriation of grunge, but it was a look that is distinctly ‘Melbourne’ in other ways—the just-rolled-out-of-bed gamer-cum-artist look. Another striped shirt was tied around his waist, with the body of a crisp white men’s shirt stiffened in place behind him as he meandered in a figure 8 or infinity symbol around the cars in white socks and no shoes, pausing twice, briefly and nonchalantly, under the unforgiving down-lighting at the centre of the room.

Milos, Spencer’s childhood friend and third nodel to appear, came out holding a Ziploc bag of suspicious green herbs like a clutch, cementing the bong-den ambience. The ghostly ‘ooOoo’ of a contemporary classical libretto played, composed and performed by Robert Ashley with whispered back-up vocals as my father, Arthur, entered wearing the sixth look: grey paint-splattered sweatpants, dragging on the concrete under his feet, and a white button-up with a white singlet layered over the top. Down the front of the singlet was a trail of weed-like herbs as though he’d been absent-mindedly consuming marijuana like popcorn. The paint on the sweatpants wasn’t the dribbles and splatters of Jackson Pollock, but smudged and blotchy, at hand-height only, as though they were the remnants of labour on a painter’s workpants.

Beyond these wry references to cheesy hippie counterculture revivalism, each accessory seemed to reference social codes or signals. One such accessory in Milos’ first look was a purple star-print handkerchief hanging out the side of his jeans with a cluster of gold glitter affixed to one corner and scattered out from it. Like John’s grunge-to-egirl look, this is a time-honoured tradition. The most immediate connotation of this item of flair was, for me, the ‘Handkerchief Code.’ The Hanky code or ‘flagging’ originated with Goldrush-era cowboys and miners who would signal which part of the square dance they’d take during shortages of female dancers, with hankies worn hanging from the belt or the back pocket of some jeans. Then, Bod Damron’s Address Book (1964) and Larry Townsend’s The Leatherman’s Handbook II (1983) certified the code in tables and lists that signalled top/bottom polarities and fetishes through colour and the side of the body on which it is worn. This is the social language of dressing par excellence, the literal (or at least more overt) transmission of signals through costume.

The fifteen-look collection, described to me as menswear, was punctuated by two dresses worn by Jasmine Pickup. The first again referenced workwear, a wrap dress waxed and stiffened with a wash of glue and starch in minty scrubs-green and what looked like a puffy tulle ruff collar. Jasmine’s movement was truncated by the stiff materials and her steps made short by the restrictive tapering of the garment at the ankles, which pulled tight with each footfall. The second dress, another floor-length wax-treated gown in the same dentist-scrubs green, was this time flared at the ankle with a belt or sash that splayed open at the back like a slashed obi and accessorised with a Coca-Cola can in hand. The only female in the show, appearing twice in similar looks, Jasmine felt like a minty fresh palette cleanser.

Like Jasmine’s ruff collar there were several items that felt anachronistic in a collection that progressively resembled traditional menswear with each new look. From the cummerbund worn by my father as an acapella Irish folk song played to John’s third appearance wearing a giant safety pin around his torso like a bow and arrow quiver bag. There was a confusion of menswear archetypes and trajectories. It was not clear whether this was streetwear, workwear, formalwear or even menswear. Only that it was ‘costume.’ With his blue hair fluttering behind his safety pin weaponry, John, second from last in the show, felt like the Katniss Everdeen of the parade. Beneath the comical hardware, he wore a crunchy (paper thin, coated cotton) suit worn open over several layered white men’s shirts, referencing a traditional three-piece suit. The folk song ended abruptly as John completed his last infinity-loop and the final model, Nick, walked out in silence. The rhythmic crunch of his pants, the friction between the starchy fabric and his thighs, was the only noise in the hushed room, as he walked with his thumbs assertively tucked in his pockets. The cream jacket’s shoulders were splattered in decorative gold leaf and it was fastened with two leather buckles like a medieval military garment about to burst at the clasps.

The anachronism and inertia of In Costume captured a sense of the postmodern waning of historicity, the collapse of space time and the perpetual layering of meaning with the rapid turnover of ephemeral images. It foregrounded the illusion of newness and perpetual movement, fossilising the present as spectral costume—the peculiar stasis that lies buried beneath an accelerated psychological perception of time. Each garment carried with it the remnants of a fabricated past life, or lost future—like when Lisa Simpson discovers the hoax angel fossil (Lisa the Sceptic S09E08) on an archaeological dig, which later turns out to be a publicity stunt for Heavenly Hills Mall (‘The End will come at sundown,’ ‘The End … of high prices!’). The apocalyptic existentialism and critique of consumption found in this episode of the Simpsons was threaded through the In Costume runway, encapsulating the accelerated temporality (or seasonality) and disposability of brands, styles and archetypes.

I should mention, Brendan is the only person I know not to have seen more than a couple of episodes of The Simpsons. I know Brendan very well and he returns to Canada early next year after almost a decade in Melbourne. It will not be possible for him to return in the foreseeable future because he’s exhausted all visa opportunities. For me, this encapsulation of a time and place that he has spent his entire twenties in is also a little farewell. Melancholic and spectral as it may be, it is also a celebration of people and personal style in a community he has become a kind of pillar of. Given the confused cyclic temporalities of In Costume, it seems appropriate to say (without the sarcastic undertone): we’re missing you already Brendan.

Audrey Schmidt is a writer and Melbourne Personality.