Eadweard Muybridge, “Sallie Gardner”, owned by Leland Stanford; ridden by G. Domm, running at a 1.40 gait over the Palo Alto track, 19th June, 1878 (1878 cabinet card, “untouched” version from original negatives), Public Domain

Horse Girl Energy

Scott Robinson

“Now!” he would silently command the snorting steed. “Now take me to where there is luck! Now take me!”

– D. H. Lawrence, “The Rocking-Horse Winner,” 1926

If you speak of horses to a djieud, the noble of the tent, who still plumes himself on his ancestors having fought with ours in Palestine, he will tell you:

The mounting of horses,

The letting slip greyhounds from the leash,

And the clinking of ear-rings,

Draw the maggots out of your head.

– E. Daumas, The Horses of the Sahara, and the Manners of the Desert, 1863

You should not look a gift horse in the mouth, nor eat like a horse, nor put the cart before it, nor flog a dead one; you should get off your high horse, take your tips straight from the horse’s mouth, hold your horses, trust horse-sense but not horse feathers. These proverbial lessons in decorum take the historical intimacy between humans and horses for granted. Before the industrial revolution, horses were among the necessary accompaniments to war, conquest, migration, trade, and labour, even as they could also be symbols of status and luxury.

As Kenneth Clark observes in his 1977 volume Animals and Men, horses are attractive to artists for their embodiment of beauty and energy, uniting exquisite poise and grace with restless, frenetic power. He writes, “The splendid curve of energy—the neck and the rump, united by the passive curve of the belly, and capable of infinite variation, from calm to furious strength—are without question the most satisfying piece of formal relationship in nature.” Clark gives voice to an obsolete tradition, rendered archaic not only by transformations in the role of art, but also by the fall of the horse from its privileged role in human lives. The loss of everyday intimacy with horses has also rendered their symbolic and mythic functions parlous. They are a floating signifier, one “hobby” among any other the discerning consumer might choose.

George Stubbs, Whistlejacket, 1762, Oil on canvas, 292 x 246.6 cm, National Gallery, London, Public Domain

The beauty of the horse has been so refined as to be arch and fragile, with words like “prancing” suggesting mere silliness. Their superlative physical energy is constrained by what Tara Heffernan calls “the rigid pageantry of equestrian dressage” and the tight coils of an over-groomed mane. On the other hand, the reverence for the horse’s remnant power in racing hardly bothers to disguise the sport’s factory conditions, ruthless slaughter and fundamental link to gambling. On the stuffed regional train from the Latrobe Regional Gallery in Morwell, the conductor solemnly and dutifully announced to commuters news of the death of Black Caviar. Hailed as a “champion racehorse,” her retirement consisted in a breeding regime producing disappointing progeny like Prince of Caviar and Out of Caviar, and whose stallion sons still earn their owners thousands of dollars to impregnate mares. Under the pressure of the commodity form, any attempt to retain the mythic significance of the horse amounts to ideological mystification.

Titled Horse Girl Energy, the exhibition promises to tap a thinning vein of equine enthusiasm surviving in cultural objects from The Saddle Club’s various incarnations to Gillian Mears’s persistently horse-bound stories, in which loss and hardship mingle with discovered pleasures and momentary freedoms won through physical assimilation with the horse. The title cannily recalls a meme from 2018 concocted as an antidote to that other “masculine” energy of the same phosphorescent instant in social media cycles. As Charles Chenevix Trench observes in A History of Horsemanship, since their banishment from the battlefield, “it is commonplace that in Pony Clubs camp girls outnumber boys by three or four to one.”

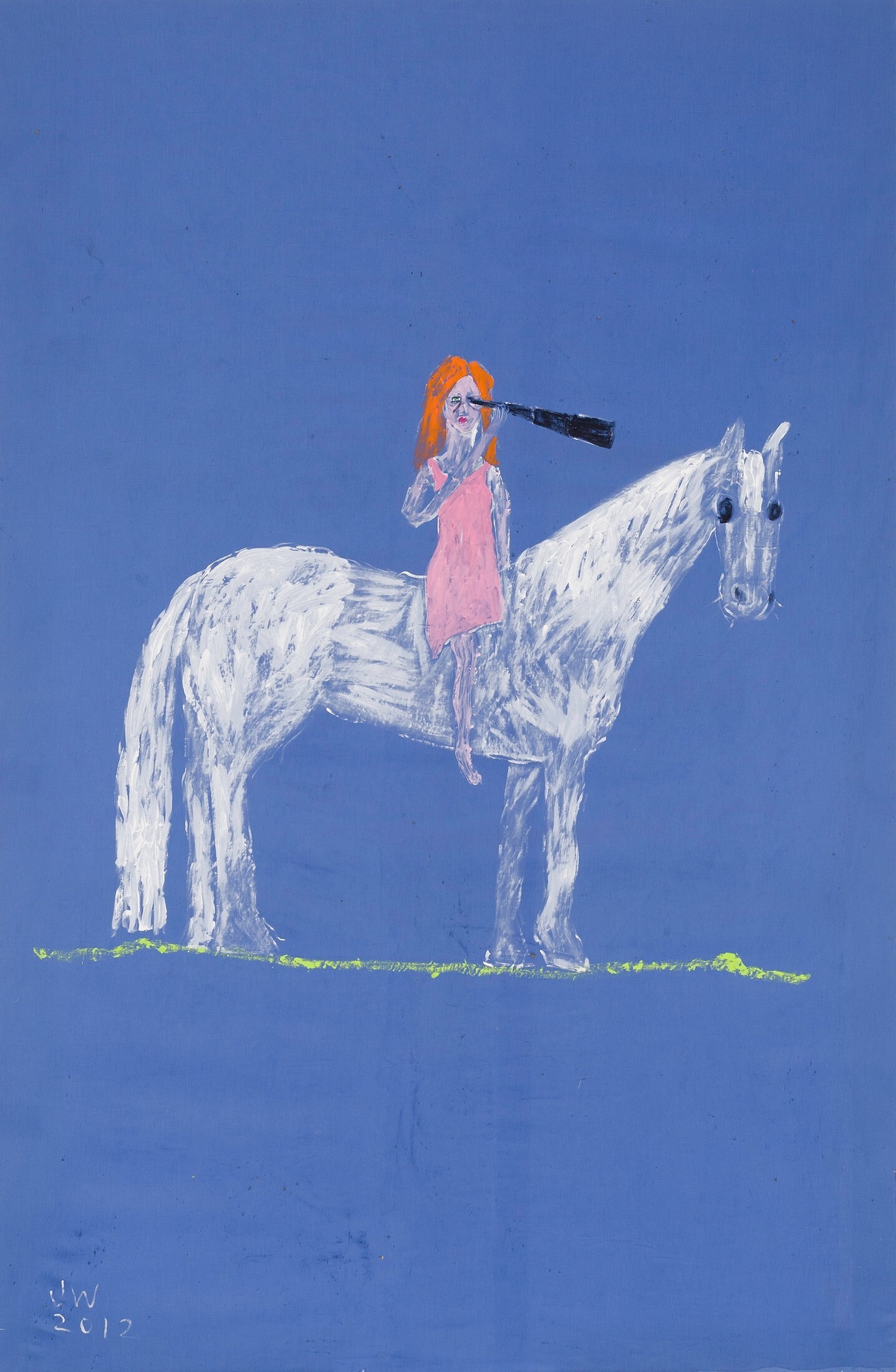

Jenny Watson, White Horse with Telescope (detail), 2012, synthetic polymer paint on rabbit skin glue primed cotton 200 x 130 cm. Latrobe Regional Gallery Collection. Courtesy the artist and Anna Schwartz Gallery, Melbourne.

The visitor is confronted at the entrance by Jacqui Stockdale’s life-sized Such is Love (2020), whose mounted figure wears a Ned Kelly helmet and brandishes a rifle, cradled across exposed breasts and a pregnant belly. The sculpture is pale white except for the metals of the rifle and helmet, the horse’s hooves, snout and eyes. With little contextual information provided by the gallery, the viewer may suppose the figure to be a female Ned Kelly, an appropriated outlaw. Juliette Hanson in a 2020 catalogue essay for The Long Shot suggest the rider is Kelly’s pregnant lover, and indicates that the horse’s proportions belong to Phar Lap. Charles Trench’s note that Kelly’s sister Kate was a “sort of despatch-rider and contact-girl” invites an alternative, her life shaped by horses from accusations of horse theft against the family and marriage to a horse-tailer after Ned’s execution when she was seventeen. Although it appears connected to Such is Love, Unwelcome Stranger (2020) is a separate work consisting of a gold-leafed pile cast from horse shit and, according to Hanson, “signifying the gold rush.” Notwithstanding Freud’s iconic association between gold and shit, the pile of shiny poo is too scatological to invite serious reflection on colonial political economy.

While striking, the stillness of the work ebbs the drama from what otherwise draws on epic myths and anticipation of revenge. Like the accompanying diptych from the series Ghost Hoovanah, depicting masked wrestlers posed with horses against staged studio backgrounds, Such is Love reads as a myth peddled after its redundancy. The Kelly-esque figure becomes a quixotic defender of the archaic. Similarly evoking a drama that fails to eventuate, Amos Gebhardt’s trio of photographs from a series called Night Horse exude an ominous, anxious mood. Against a dark background and swirling dust, the horses stand (in Open Cluster) and frolic (in Midnight and Fetlock). The kitsch majesty of the scene is punctured by the spray of urine at the far right of Fetlock from a horse whose tail and rump are only partially visible.

Matilda Davis, Round and Round and Round and Round, 2024, Oil on canvas, Giulia’s hair, satin ribbons, 40 x 30 x 3 cm. Courtesy of the artist and FUTURES

Two works by Jenny Watson are also prominent, if quiet, observers of the entrance. These muted paintings of bug-eyed horses stare at each other across the room. While in Feed (2019) the vigilant brown horse is accompanied by a small bird, in White Horse with Telescope (2012) the awkwardly rendered white horse carries a clumsy self-portrait of Watson. The telescope held by the figure seems to puncture or skewer her eye socket, barely grasped by the fingers of a hand that concludes with a freakishly elongated forearm, stretched across a similarly elongated neck. The viewer looks into the green eye of the woman and the horse’s staring yet empty black eyes, but the telescope protrudes laterally along the plane of the painting. It is less that the figure sees something in the distance—since no actual landscape or world is implied by the thin horizontal stripe of yellow—and more that the figure sees something we cannot, perhaps interior, or at any rate private.

Anna Davis, in her catalogue for an MCA retrospective, describes the figure in White Horse with Telescope as peering “down the barrel of her own history,” and Watson has averred that even in her earlier work “the horse was a kind of self-portrait.” Yet the transition from a refined, colourful style in The Horse Series of the 1970s to the messy inwardness of works like Passion and masochism (1985) and The inner stable (1986) is notable. The earlier, technically assured work cannot easily be retroactively absorbed into the later, looser style. The projection of the self into the image of the horse seeks to recuperate its beauty and grace. Their power and energy allows Watson the memory of “taking off and getting away from your parents.” It is a specifically class-bound image of freedom, for children dependent on their parents for funding and transport to this expensive hobby. Like a suburban Gwendolyn, in Eliot’s Daniel Deronda (1876) the rider wants “to have her blood stirred once more with the intoxication of youth, and to recover the daring with which she had been used to think of her course in life.” The horse promises, in practice and in phantasy, to alleviate the burdens of human corporeality, including age.

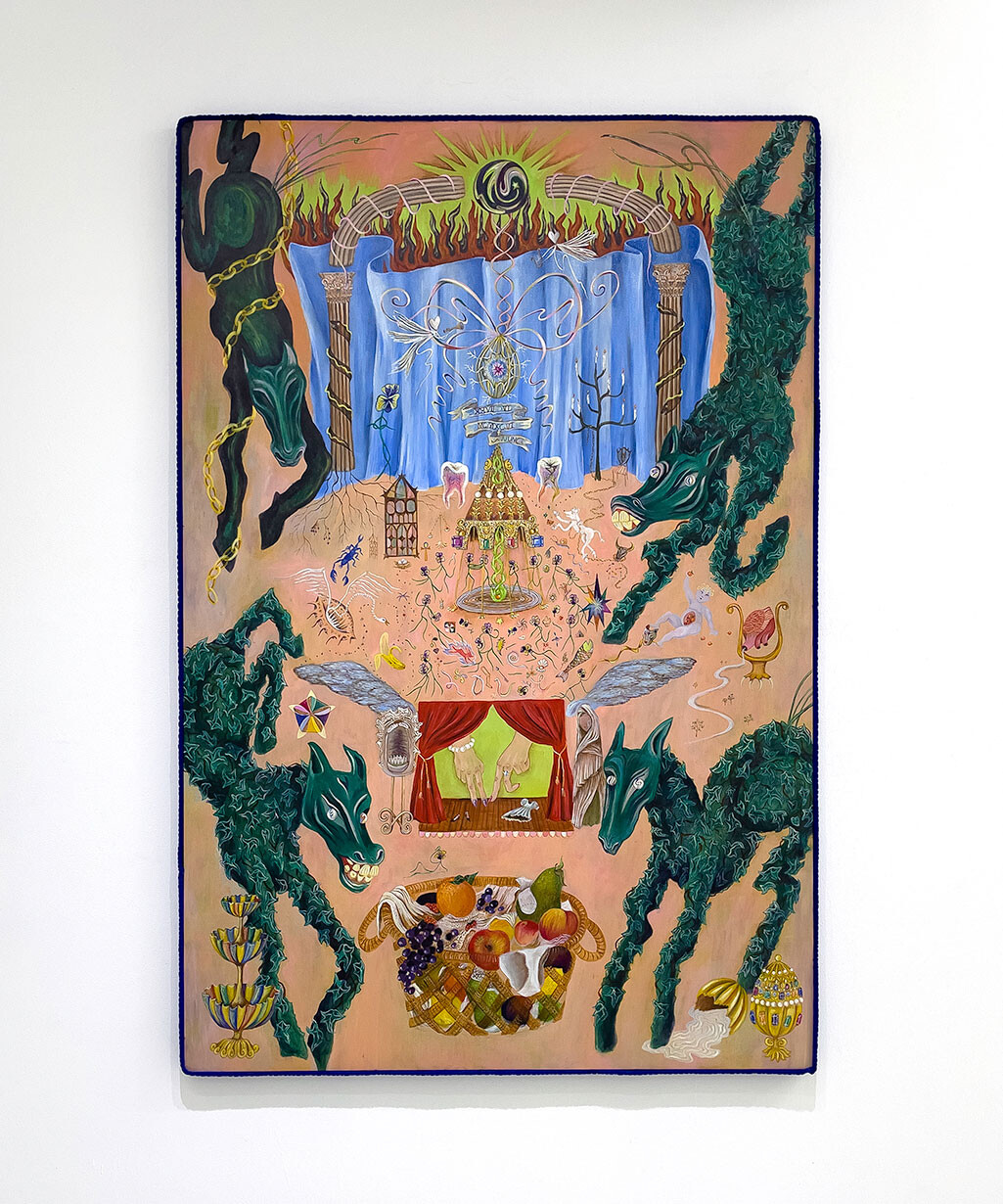

Matilda Davis, ‘Every Saint has a past, every Sinner has a future’, 2023, Oil on canvas and board, 180 x 120 cm. Courtesy of the artist and FUTURES

The inward turn is intensified in Matilda Davis’s two works, Round and Round and Round and Round (2024) and Every Saint has a past, every Sinner has a future (2023). These works evince a kind of bargain surrealism, a movement that for Walter Benjamin in 1929 had already been reduced from a liberatory current to a “paltry stream.” Round and Round offers a dualism of freedom and constraint in an image of horses dancing in a circle on a green hill, like Matisse’s women, but tethered at the centre by coloured ribbons. The horses are doll-like, their disjointed limbs rotating mechanically on hinges, their leaps turned into the static poses of a toy. The work has a pair in another part of the exhibition with Alan Sumner’s Captive Horses (1952), whose carousel bars puncture a group of horses in the damnation of an eternal circuit. In Every Saint, green demon-like figures resembling ivy-coated horses occupy the four corners of the canvas. The canvas is scattered with symbolic motifs, and its Boschian composition and elements do not quite cohere into a system. Like demonic horses with bared teeth, the symbolism strains and, like their apparently boneless bodies, crumples in odd places.

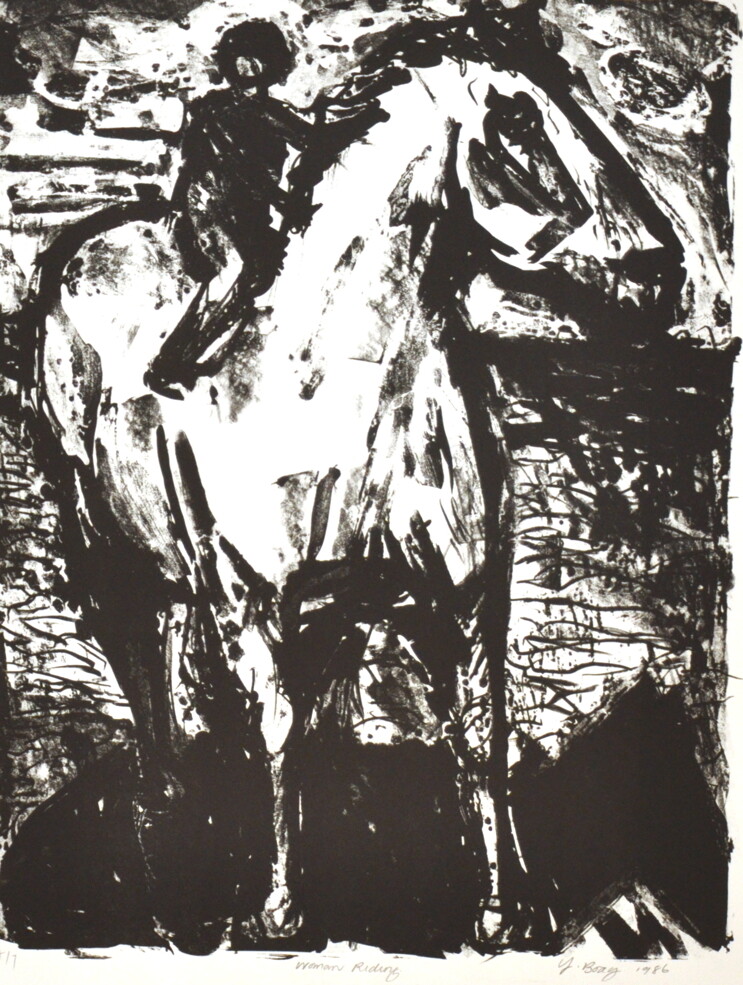

Yvonne Boag, Woman Riding, lithograph, 57 x 43cm, 1986, courtesy of the artist

Davis’s paintings hang opposite an agglomeration of objects called the “Equine Shrine.” Information about this component of the exhibition is sparse. Ostensibly sourced from the “local community,” the items and works vary from paraphernalia and kitsch to charming works of folk art and intriguing works that deserve more prominence in the exhibition. One small image depicts a balding man in a thick woollen brown jumper and jeans astride a pink toy unicorn, whose front left hoof is raised flirtatiously. So too a harlequinade horse fight pits red and yellow-patched horses against one another, the oddly-proportioned figures rearing up in black outline on a white ground. Amid naïve neo-pastoral paintings and inevitable racing memorabilia is a photograph whose white-eyed equine subject stares outward from a mysterious night-scape, as if caught by an unexpected flash. Its white coat and mottled grey face echo Gebhardt’s series, yet it has a mystery and originality that outstrip the large, over-produced scenes in Night Horse.

Installation view of Abdul-Rahman Abdullah, Dead Horse, 2022, Carved and stained wood, 60 x 216 x 290cm, courtesy of the artist and Moore Contemporary; Anna Louise Richardson, Phar Lap: Skin, 2017, Charcoal on cement fibreboard, 300 x 322 cm, courtesy of the artist; Anna Louise Richardson, Phar Lap: Bone, 2017, Charcoal on cement fibreboard, 300 x 322 cm, courtesy of the artist

These un-labelled objects are gathered salon-style, and nine works from the gallery’s collections are grouped in another corner. Though small, these works are suggestive of what has been lost in the artistic depiction of horses. Their impact is sequestered by their position in the exhibition space, but they testify to historical changes and artistic responses that are largely unreflected by the contemporary works. For example, in Ethel Spowers’s The Works – Yallourn (1933) the horse is so diminished as to be almost entirely invisible in an expressive, industrial landscape, while in Gary Shead’s Mirage (1985) the dun brown aquatint landscape seems to both gather in and recede behind the leaping horse. Yvonne Boag’s Woman Riding (1985) also immerses the horse in its surrounds. The lithograph’s dark, Lawrentian sensuality is picked out in nothing but swelling black lines and inky smudges. Boag’s horse is carved in negative space, like Alwyn Harbott’s maquette War Horse (1988), whose superbly convincing bucking motion is traced only by strands of brass wire, the spare use of which somehow manages to convey both the weighty volume of the horse’s torso and its lively strength. Finally, in Stefan Szonyi’s Contemporary Scene with Reflective Glass IV (1999) a humorous psychoanalytic scene is played by small ceramic figures, suggesting the childhood pleasures (or dangers, as in Lawrence’s story) of a rocking horse, a figure of repetition, obsession, and incipient sexuality.

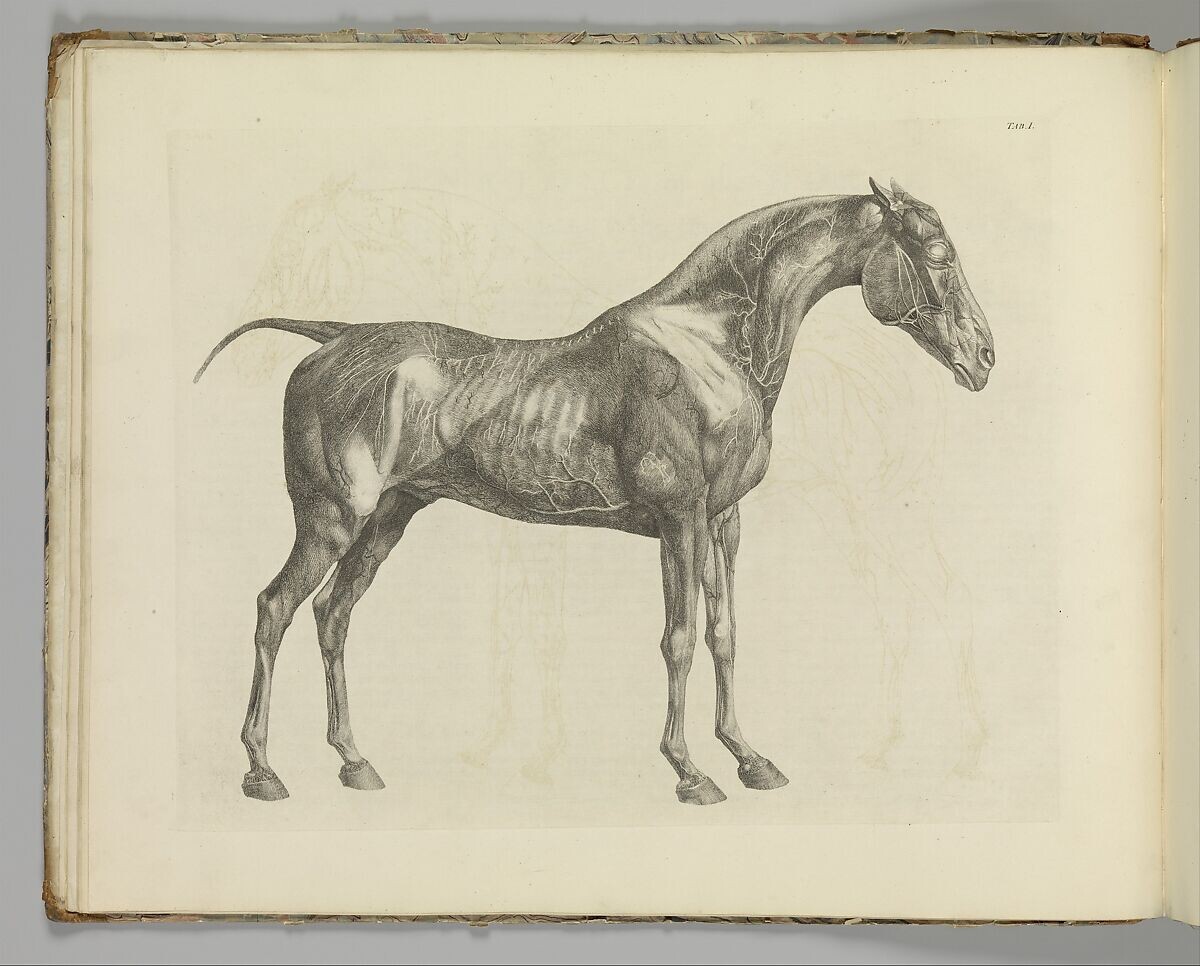

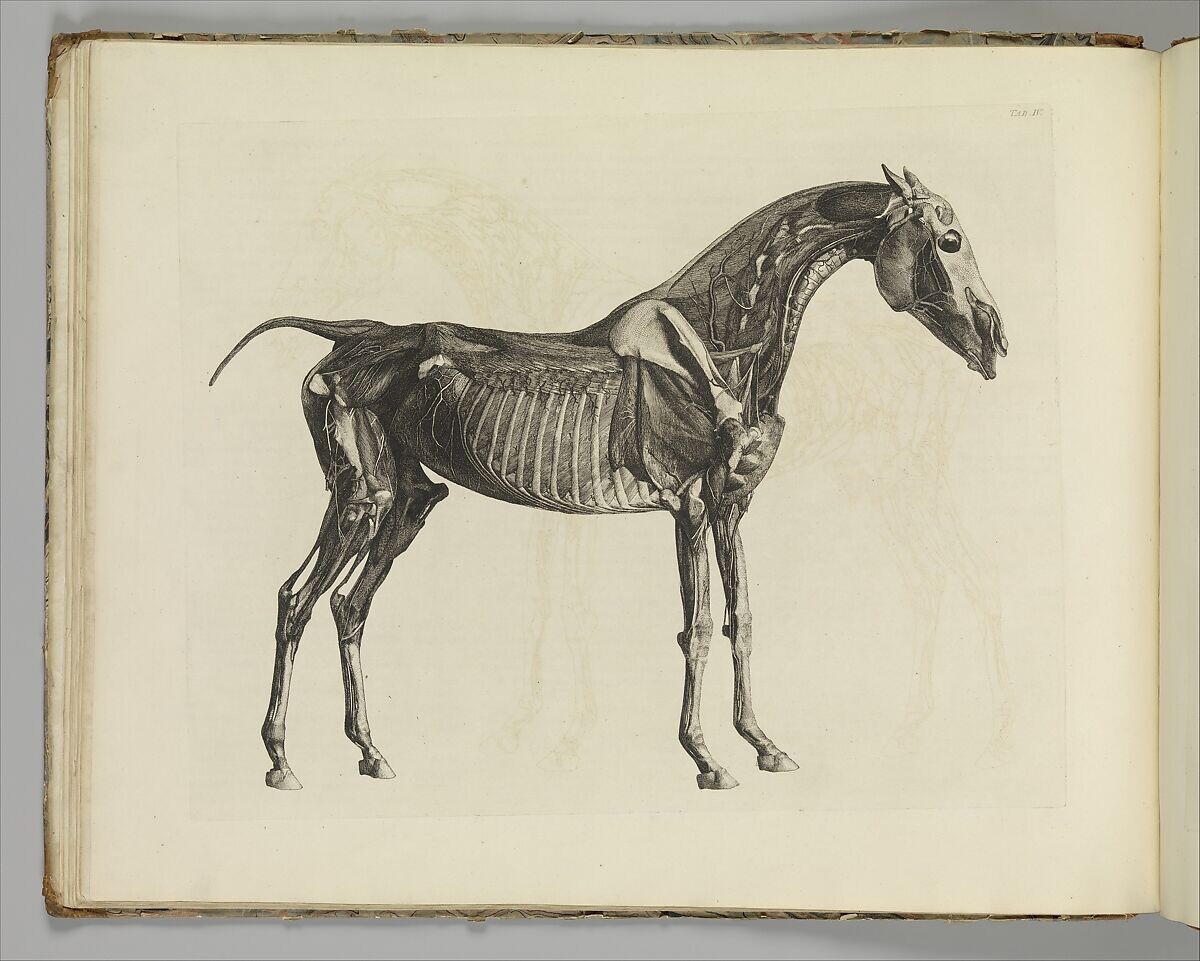

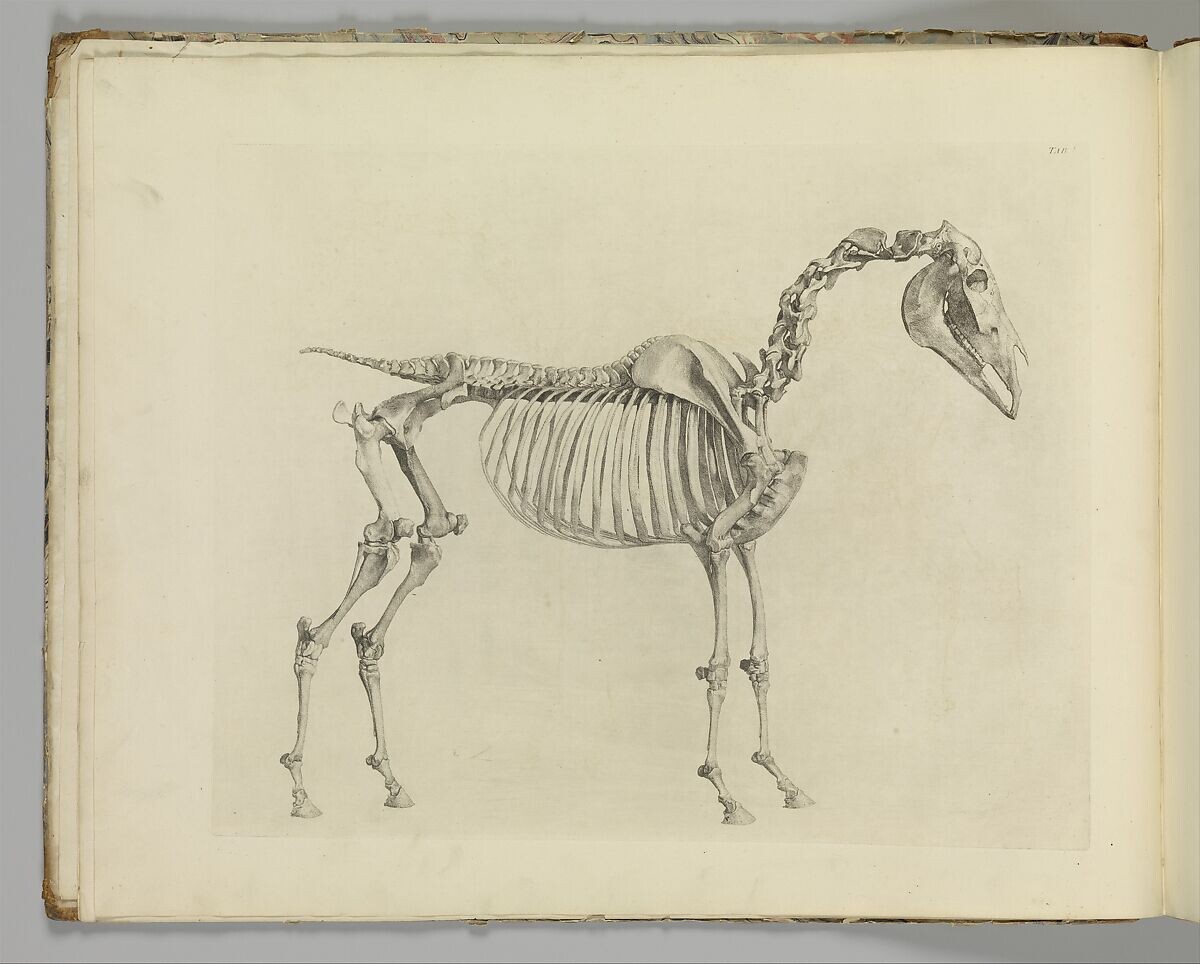

George Stubbs, from The Anatomy of the Horse, including a particular description of the bones, cartilages, muscles, fascias, ligaments, nerves, arteries, veins, and glands, 1766, 46.4 x 58.4 cm, Public Domain

In a separate room are Abdul-Rahman Abdullah’s Dead Horse (2022) and Anna Louise Richardson’s Phar Lap: Bone and Phar Lap: Skin (2017), which together melancholically ponder the post-mortem weight of a horse’s body. Abdullah’s sculpture Dead Horse sculpture is a life-sized wooden construction, with layered sections of stained wood smoothed together before being carved with flowing rivulets of tawny hair. Though labelled “dead,” the horse’s eyes flicker with natural light from the large window. Its body is uncrumpled, with no obvious signs of injury or death other than the slight concavity of its breathless cheeks and static distribution of weight. Were it not for the gazing wooden eyes, the horse could be read as sleeping. The viewer is not exactly confronted by death as by the graceful repose of a body whose stillness emanates an eery delicacy against its heaviness and scale.

Richardson’s Phar Lap diptych plumbs the integral form of the iconic race horse by pairing it with its skeleton, a morbid double. Phar Lap: Bone recalls pre-eminent English equine artist George Stubb’s Anatomy of the Horse (1766), which stages the stripping back of skin through a stunning reconstruction of muscular structure before emptying the flesh entirely to bone. The capacity of the horse’s skeleton to dramatise mortality lies in the absolute reduction and defamilarisation of its living form. You could not reconstruct a living horse from the skeleton alone, with its improbable neck and legs, spiky prehistoric curve of the back over a gaping rib-framed void and terminal stub of a tail. The only visual suggestion that the living horse in Skin is Phar Lap is the bridle and reins slung across its back. It is otherwise as motionless as the dead horse it mirrors.

George Stubbs, from The Anatomy of the Horse, including a particular description of the bones, cartilages, muscles, fascias, ligaments, nerves, arteries, veins, and glands, 1766, 46.4 x 58.4 cm, Public Domain

The horses in Horse Girl Energy are surprisingly immobile. It is as though in revealing the secret of horse locomotion, Eadweard Muybridge’s Horse in Motion studies (1878) also disenchanted it. The apparently impossible, imperceptible flight was arrested, and appropriated by proto-cinematic technology, just as the horse was decisively de-throned by the combustion engine in the next century. After a late incandescent reign in the tremendous power of Géricault’s and Delacroix’s horses, Clark proposes that the equine tradition wanes after Rosa Bonheur’s The Horse Fair (1852–55), which contains only “muffled thunder… like the distant echo of a receding storm.”

George Stubbs, from The Anatomy of the Horse, including a particular description of the bones, cartilages, muscles, fascias, ligaments, nerves, arteries, veins, and glands, 1766, 46.4 x 58.4 cm, Public Domain

The works from the Latrobe Regional Gallery’s collection reckon with these changes. Their modesty should not lead us to ignore their demythologised treatment of the horse. Ethel Spowers’s depiction of Yallourn in the 1930s, then a company town, is particularly poignant given its displacement and decline. Works by Watson, Davis, Stockdale and Gebhardt treat the horse’s mythology as given, or insert it into a private symbology. Indeed, they seem hardly interested in the horse as such, and more—as the husk of meaning represented by the meme suggests—the “energy” or “girl” who can project hidden depth and proximity to strength through association with the horsey passions. The older, minor works quietly reconstruct, in the face of obsolescence, meaning from the captivating liveliness of real horses. They do not shy from the insight that, among the horse’s many charms, their majestic power and graceful force, lies the pathos of an affair with beauty that has—like art itself—been almost entirely abdicated to the realm of hobbyists, charlatans and mercenaries.

Scott Robinson is a writer, academic and unionist, published in Overland, MeMo Review, Index Journal, Arena, Monthly Review, Artlink, ArtsHub and elsewhere. He is currently associate editor at Philosophy, Politics, Critique.