Gary Lee, Mindil to Mayarrang. Photographed 2021, printed 2024, type C print on Ilford cottonrag paper. Photo courtesy Swarf

Heat/Keep Him My Heart

Giles Fielke

There is a footnote early on in Mike Davis’s 1990 study of Los Angeles, City of Quartz, which claims the English occultist Aleister Crowley once wrote to Trotsky congratulating him on the success of the revolution. Crowley then offered to the Comintern his services for the “extirpation of Christianity on earth.” Crowley’s influence on the American rocket scientist Jack Parsons, who in turn played a significant role in the early days of Scientology, before blowing himself up at his house in the L.A. County city of Pasadena in 1952, is fundamental SoCal lore. The rapid development of military-industrial infrastructure in the American West is offered by Davis as the other side of the dollar-driven economy symbolised by Hollywood from the 1920s on. Crowley’s liberal maxim “do what thou wilt” still appears to epitomise L.A. today. Considering California as a whole, named as it is for the fictional Queen Calafia, the twentieth-century experiment in the transvaluation of all values often produces strange results. The word California is rooted in the word caliphate, after all. Crowley’s letter, at least according to Davis, also explicitly noted his hatred of capitalism. Trotsky did not reply.

There are aspects of these seemingly impossible alignments that might help discern the work of Gary Lee. He once corresponded with David Attenborough, for example, but not about Christianity (Attenborough also responded). Lee’s exhibition Heat/Keep Him My Heart has been open at Swarf since 12 October. From the so-called “Northern Territory” of Australia where Lee was born and still lives, he has worked for more than four decades within the “frontier” still active in the national imaginary. Given the strategic military installations also located there (Lee’s house is surrounded by a military base), Garramilla/Darwin might qualify as a type of L.A. “down-under” and the territory our California in the sense that it epitomises the country’s archetypal landscape, symbolised by internationally recognised locations like Kakadu and Uluru. This operation is a representational mirage, enacted to cover over the expropriation of country identifiable mainly for its resource potential, as well as addressing the fact of the dispossession of its First Peoples by seeking to offer a more aesthetically and economically pleasing alternative: development. There are, of course, other histories here that reveal the paucity of this representation. History is only the history of the present, so we’re told. Heat/Keep Him My Heart presents us with Lee’s history.

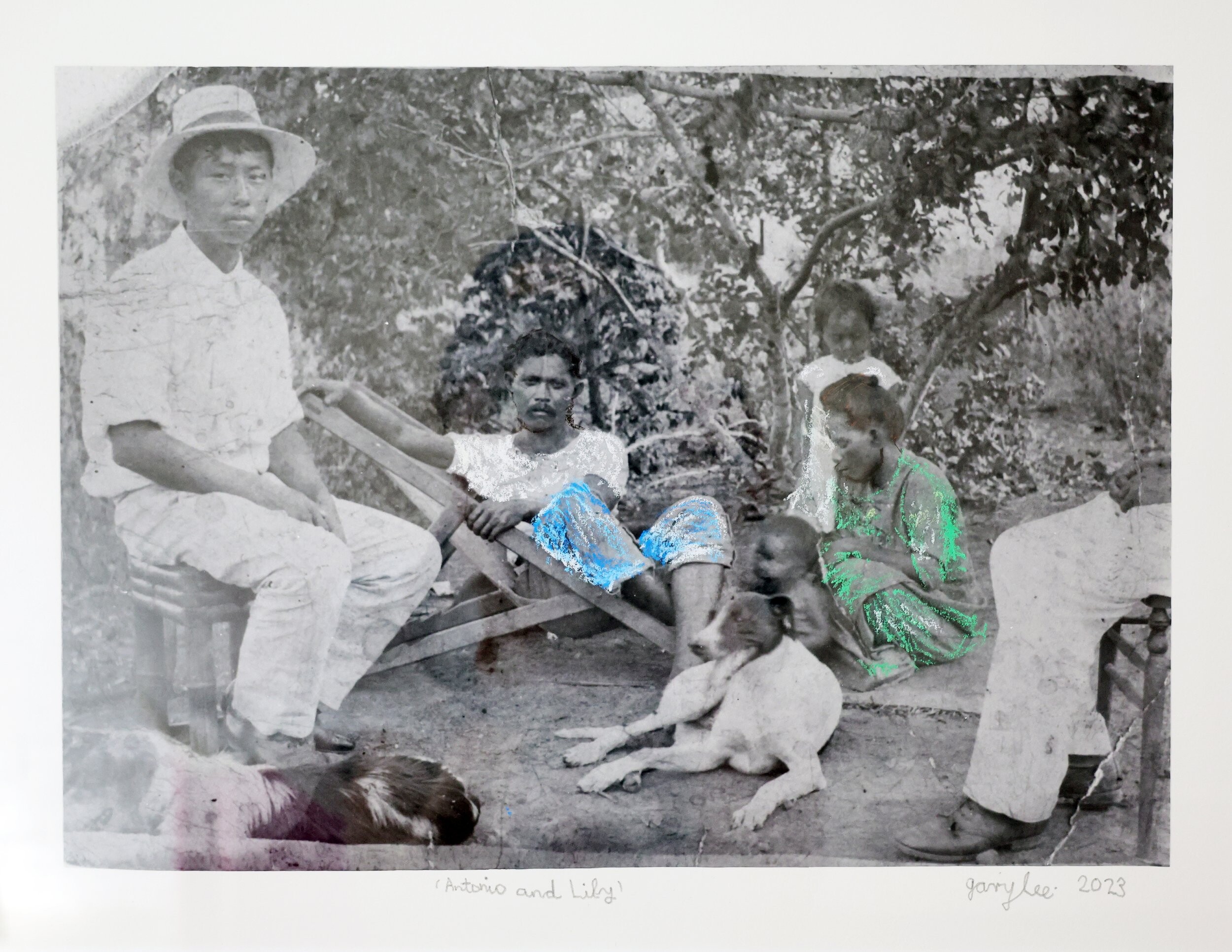

Gary Lee, Antonio and Lily, 2023. Pastel, pencil on type C print on Ilford cottonrag paper. Photo courtesy Swarf

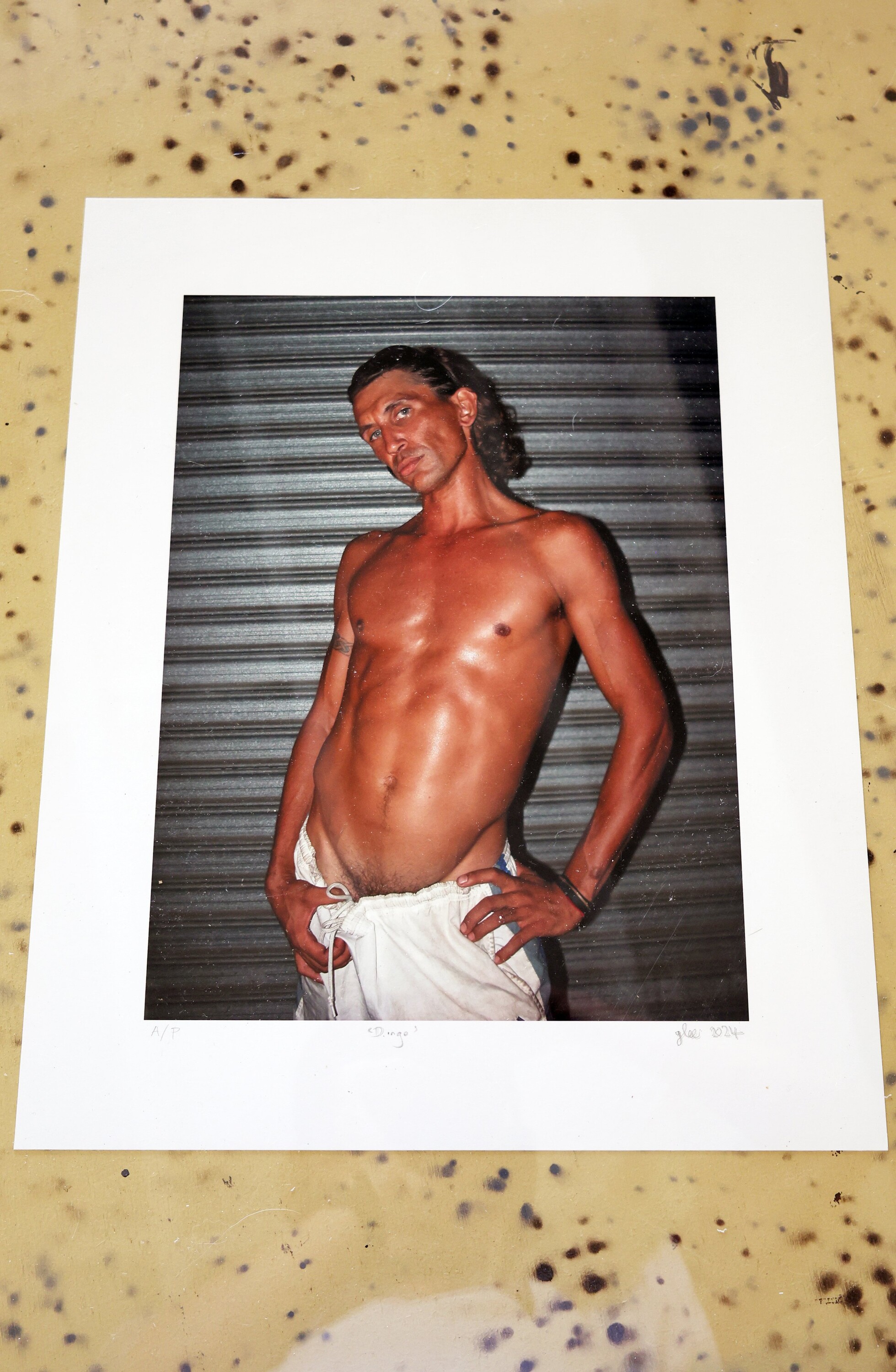

Lee’s grandfather was a dockworker and musician who was killed in one of the sixty-four bombing raids on Darwin by Imperial Japan between February 1942 and November 1943. Lee himself was born in Darwin in 1952. (Welcome back Jack Parsons?) In the 1980s he studied art in Sydney and then anthropology at the Australian National University, before returning to Darwin with an honours degree to work at the Northern Land Council. He also experienced early success as a fashion designer in Sydney, before giving it away to return home. Remnants of his prior vocation might be glimpsed in works on display at Swarf that connect heat to heart. Photos like Lily, Corroboree (1997/2014), or the drawing Working sketch for subverted Ned Kelly (2023). Dingo (2006/2024), a brightly lit portrait that might be mistaken for a Vice era shoot by Terry Richardson, is from the Darwin Lads series, and provides some kind of continuity between the then and the now.

Gary Lee, Dingo. Photographed 2006, printed 2024. From the Darwin Lads series. Type C print on photographic paper. Photo courtesy Swarf

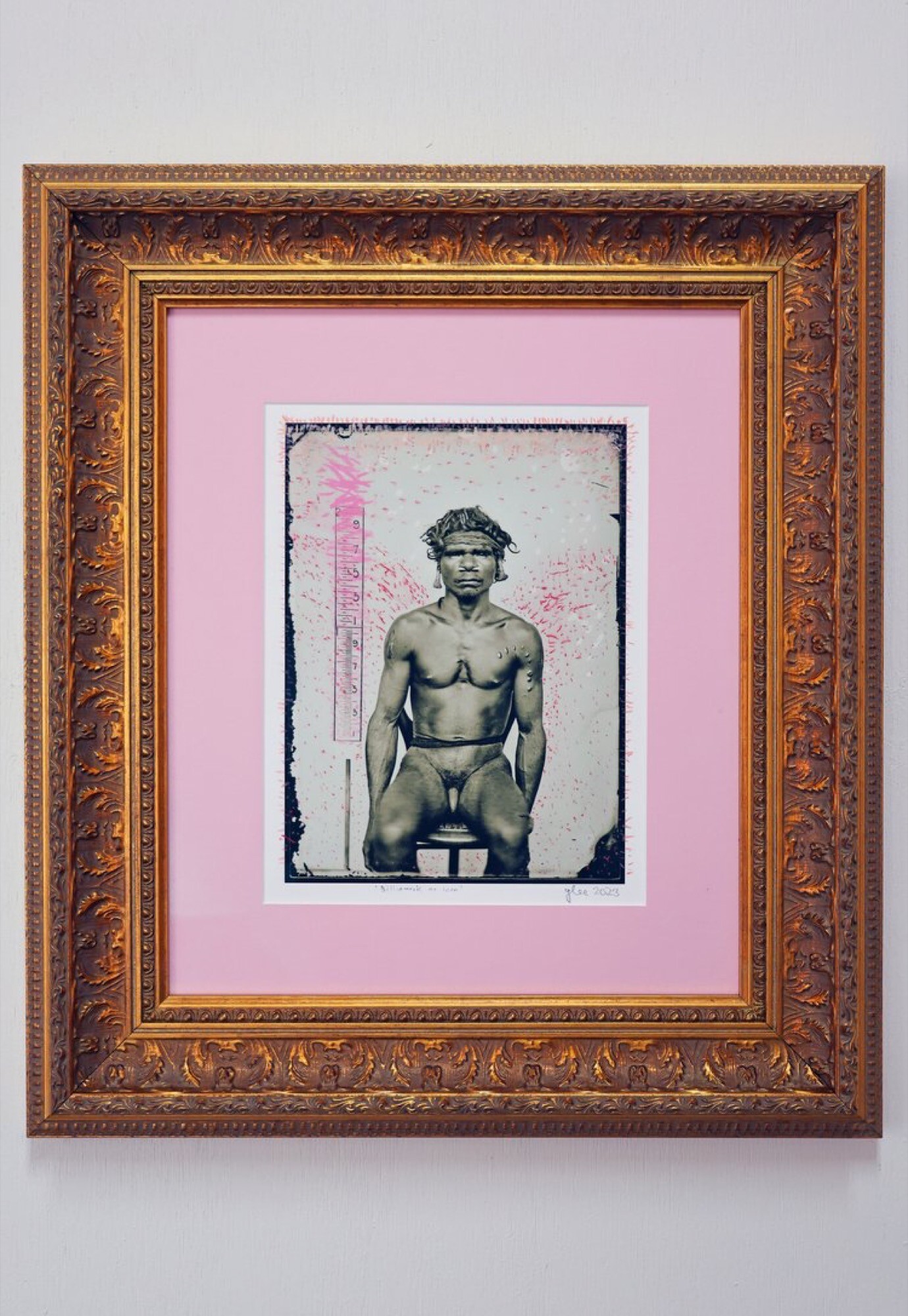

At Swarf, Lee signs his recent prints with pencil, in a shaky, cursive script: “glee.” The Larrakia anthropologist, curator, writer, and artist, suffered a stroke in late 2007, meaning he now relies on a wheelchair for mobility and writes with his left hand. This includes the pastel, pencil, and texta additions he has made to some of the photographs on display, a number of which he has located in archives, and at least one, Billiamook as icon (2023), was taken nearly 150 years ago. Another, Nagi (2023), depicts Juan (John) Roque Cubillo (Lee’s maternal grandfather) garlanded by pastel flowers. A different version of this work won the Telstra NATSIAA Work on Paper Award in 2022. The NGV has collected an earlier version of Billiamook at icon (2020), but the version as Swarf is better, with its pink mat and pastel additions proposing angelic potentialities. The marks of age, aging, ability, and institutions are found (sometimes performed, sometimes literally) on Lee’s people. His work has always prioritised portraiture, most spectacularly young men with beautiful bodies. Self-portrait with Manish (2002/2023) stands out on the cover of Heat, the recently published anthology of his writing, which also serves as one part of the show’s title.

Gary Lee, Billiamook as icon, 2023. Pencil and pastel on type C print on Ilford cottonrag paper.

Beyond the ease of drawing out his association—literal or comparative—with his contemporaries, artists like Tracey Moffatt or Fiona Foley, Lee’s work might also just as (un)easily fit somewhere between works by Drew Pettifer or even Tony Greene. Lee’s foundational series, not explicitly included in the Swarf show, is Nice Coloured Boys. It was initiated when he was working as a guest curator for the Department of Foreign Affairs in Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, Nepal, and India in 1994. It suggests the direct, disarming, erotic charge of the camera and can be seen to encompass newer series like Darwin Lads. Tristan Harwood, who co-curated the exhibition with Swarf’s director, Lauren Burrow, understands Lee as an artist of “otherwise,” the queer and Indigenous histories that persistently evade (and survive) Linnean categorisation. Yet Lee’s objectifying focus is tempered by the conceptual project he appears to have been quietly undertaking, which bifurcates to propose the human body as a corollary of country, in distinction from the landscape tradition of Western art history, which often seeks to isolate people in the “natural environment.” This recent aspect of his photography coheres and complexifies the exhibition in spite of the oftentimes quaint one-dimensionality of the images. The studied curation and installation of this selection of Lee’s work is also what makes this exhibition such a stand-out. It is easily the best show I’ve seen all year.

“Landscape,” Tom Mitchell writes in 1994, “(whether urban or rural, artificial or natural) always greets us as space, as environment, as that within which ‘we’ (figured as ‘the figures’ in the landscape) find—or lose—ourselves.” This follows the “dark side of the landscape” that can effectively be understood as economic and material considerations of the “medium” (essentially, enclosure). “Is it possible,” Mitchell asks, “that landscape, understood as the historical invention of a new visual/pictorial medium, is integrally connected with imperialism?” For Lee this was stating the obvious, but it also presented a problem: could landscape be otherwise, especially as photography? The installation of Lee’s landscape photographs here are the most curious addition to his work in this show, and a closer consideration suggests how they might relate to the other part of the show’s title, Keep Him My Heart.

Lee’s images—mostly photographs, sometimes embellished by drawing, some taken by him, others found in archives—operate alongside his writing, and seem to accept from the outset the thoroughly objectifying gaze of the camera. The camera documents alongside the legal documents that sustain a complex and often paper-thin sovereignty over the country. This Nietzschean approach to art as exploitation, extends to the traditions for image-making imported from the neo-classical academies of Europe into this country. The opening lines of Lee’s essay, ‘Lying about the Landscape’, which was first published in 1997, reveal the directness of his vision: “It’s puzzling that there is a debate at all about the so-called landscape tradition in the history and practice of white Australian art,” Lee writes, “it is blindingly obvious what the function of the landscape tradition is: it is about the theft of indigenous land.”

From the image Raining at Parap Camp (1956/2023), which captures Lee at four years old, to the recent photos Dripstone (2021) and Mindil (2021), the connection that allows Lee to navigate the camera that takes portraits and the same that captures the landscape is found in a play he wrote by chance. At the opening of the exhibition, scenes from Keep Him My Heart: A Larrakia-Filipino Love Story was read in the gallery with Lee and his family and friends present. Originally staged (for six performances only) in Darwin in 1993, the play was re-published this year by dishevel books, in an edition that collects an additional raft of information about the work and Lee’s family history. Maurice O’Riordan published the book, following the edited collection of Lee’s writing as Heat (2023). O’Riordan is Lee’s partner, and last year curated the exhibition at Coconut Studios, midling (Larrakia: Together), to which this show feels intimately related. He was also the editor of Art Monthly between 2008 and 2013. Lee’s sister is a senior curator at the National Gallery of Australia. As such the familial and art as identity nexus is present here in the extreme. Again, this grates—quite deliberately—against assumed models like the “separation of powers” or “conflicts of interest” that underpin colonial representation.

Gary Lee, Raining at Parap Camp, 2023. Pastel, pencil, texta on type C print on Ilford cottonrag paper. Photo courtesy Swarf

Lee’s work was included in More Than My Skin, an exhibition “illustrating Aboriginal maleness whatever that may be,” curated by Djon Mundine and first shown at Campbelltown Arts Centre in 2008. Lee co-curated a show with O’Riordan, Love Magic: Erotics and Politics in Indigenous Art, at the National Trust’s S.H. Ervin Gallery at Barangaroo in 1999. Alongside Lee’s own work, they showed work by thirty-four Indigenous artists, including Brook Andrew, Fiona Foley and Judy Watson, to name only a few. In these two examples only, it is clear that current attempts to frame “identity” as a recent motivating force in contemporary art has a much longer, subterranean, and long-lasting history, especially for Indigenous and queer people. In 2004, the late Okwui Enwezor contributed an essay to the Australia and New Zealand Journal of Art (the art association which runs the journal recently awarded this year’s best art writing by an Indigenous Australian prize to Lee’s book Heat), in which he notes the admixture of political interest, sociological, aesthetic, and archival concerns as the most consistent thematic of the work he found most compelling at the time. Listing works by artists like Allan Sekula, Steve McQueen, Ulrike Ottinger, and Jef Geys to illustrate the role of documentary between ethics and aesthetics in contemporary art, Enwezor tracks a real shift (when he died in 2019, the New York Times called it a remapping) in contemporary art. Today it feels like we have witnessed and foresworn the apotheosis of this movement, yet I imagine that Lee’s work remains undervalued, and under-appreciated—even unknown—despite its centrality to this era of art.

This is why Heat/Keep Him My Heart feels so novel in its approach, but it is also limited to its local concerns. This is work that has existed in essence for decades but is only now being externalised. When Swarf was founded by Burrow, who grew up in Darwin, its website prioritised its basis on the unceded Wurundjeri lands in Naarm. Heat/Keep Him My Heart is the second show at the ground-floor gallery space. The gallery itself eschews institutional white cubism in preference for something closer to a community arts org operating amongst other studios and creative spaces. A roller door and an adjacent vacant lot in a suburban street, the blonde brick building is the site of the former Austramax factory, a family business specialising in kerosene pressure lamps, which closed only last year after trading for more than eight decades. There is little of the global contemporary art world to be found here, but it is certainly aware of it. The emphasis on the specifics for the installation of the show seeks to reinforce the long-simmering contingencies of Lee’s work: Besser blocks; painted pine; a Banyan Tree prop that cites a set design sketch Lee made for the play. Yet the iconography is universal.

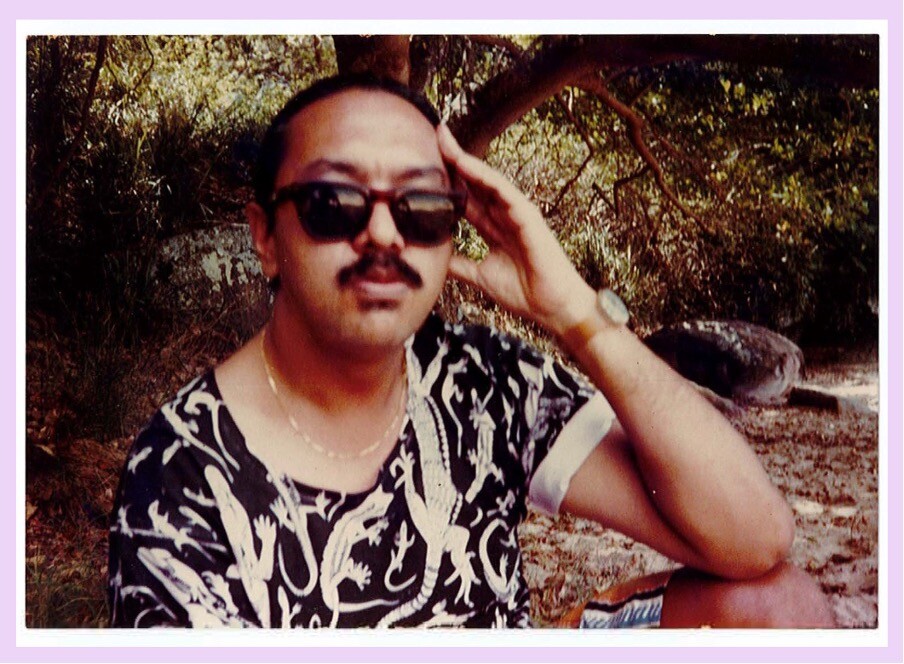

Gary Lee in Sydney, c. mid-’80s wearing a T-shirt from Tiwi Design with ‘Lizard design print’ by Angelo Munkara and Ray Young; photographer unknown. Reproduced in the article “Aboriginal art ripoff,” heat: selected texts & anthropology (2023), 40-1. Article first published as the foreword by Gary Lee, Aboriginal Students’ Association, Australian National University (ANU), to an article Rag Trade Art Heist, on the theft of Aboriginal art, reprinted from Land Rights News, December 1987 in Worona, ANU newspaper, 24 March 1988, page 24.

Keep Him My Heart tells 100 years of family history in Darwin originating with the Filipino-Spanish sailmaker Antonio Cubillo, who started a family with Magdalena McKeddie, who was known as Lily. They would have ten children, so the genealogy is complex from the outset. In an interview with the Solidarity Philippines Australia Network from 2006, Lee describes how Antonio became stranded in the Philippines during World War Two, dying there in 1950. Incidentally, Cubillo was from Bohol, across the strait is the island of Mactan where the Portuguese colonist Ferdinand Magellan was killed during the first circumnavigation of the globe in 1521. The modern nation was named for King Philip II in 1542, the islands eventually becoming Spanish possessions. There is a further resonance here for the British colonisation of Australia, following the British occupation of Manila prior to the Cook voyages, and the discovery of Spanish charts of the Torres Strait

Lee’s play has its origins in a chance meeting between Bong Ramilo and Lee in Sydney in 1991, supposedly in the lift of the Australia Council for the Arts offices. Ramilo composed the music. Some of Lee’s work, including archival materials related to the play was collected by AIATSIS in 2013 (MS 5025). Interestingly, it states: “The music, (is) specially composed for the play by Filipino artist Bong Ramilo,” who had first arrived to live in Australia only a few years earlier to work in theatre, and that “it is based on the Filipino Rondalla (string band) musical form, which was introduced to Darwin by Antonio Cubillo with the creation of the ‘Cubillo Brothers Guitar Orchestra’ in 1915.” The band inspired the formation of the Darwin Rondalla for the staging of the play in the 1990s. The original group is now considered an important part of the so-called “Bush Ballad” form of folk music, which includes ‘Waltzing Matilda’, typically attributed to Banjo Paterson (the Cubillo Brothers would also inspire a scene in Baz Lurhmann’s 2008 camp-epic, Australia).

Model citing Gary Lee’s sketch for the play’s focal banyan tree prop which was a handbuilt tree on rollers. In the background: Nagi, 2023. Pastel, pencil on print on type C print on Ilford cotton rag paper. Photo courtesy Swarf

In the third act of the play, Cathie (Lee’s aunty) recounts this in the context of the Kenbi Land Claim for the Larrakia people and for their family of mixed heritage.

After Dad got killed on the wharf during the bombing of Darwin, you remember? Then we all had to be evacuated to Balaclava and Native Affairs just put any label on us like ‘Asiatic’, ‘half-caste’, ‘quadroon’ or even ‘octeroon’.

The family’s humble exasperation with colonial administration goes further than the obviously deleterious effects of biological racism during White Australia. There is a physical connection to country that is present here too, unmediated by labour. Cathie reflects, “Ahh.. our poor old country. We keep him our heart. Nobody can ever take that away from us … Larrakia people.”

This week the Kenbi Land Claim has been finalised after forty-five years. It encompasses the Cox Peninsula, which faces Darwin from the west. You can catch a ferry from Cullen Marina near Fannie Bay—the site of the old jail where the Police Inspector and photographer Paul Foelsche worked. He took the image of Billiamook in 1879—to the small resort town of Mandorah on the peninsula, or to the Tiwi Islands to the north. The Kenbi Land Trust and Larrakia Development Corporation are now administering about 600-square kilometres of land and water there. In effect it is the symbol of the project to “develop Northern Australia” set out in a White Paper by the Abbott government in 2015. “Economic potential” is the central concept. A proposed Larrakia Cultural Centre has just begun construction in central Darwin at Stokes Hill.

In 2024 this vision expands to mean any part of Australia that is north of the Tropic of Capricorn—Larrakia country figures as only a small part of this project. This is a frontier, like the American West in the nineteenth century: where fortunes will be made and lost, where the future is about to arrive. But Lee’s project is concerned with the “old” Darwin, and with artistic representation that he understands as “presenting identity on the terms of those who are living it.” Lee’s body of work, therefore, becomes one, major, aesthetic marker of the shift to envision a region that is closer to South-East Asia than it is to the United Kingdom. Timor Leste, Indonesia, Papua New Guinea, West Papua, Singapore, Malaysia, Vietnam, Laos, Cambodia, and the Philippines: it is an archipelago home to 700 million people, even before you reach China and India. It is also in this sense, I gather, that people and landscape might be understood as country. Like city and citizen, perhaps.

Giles Fielke is an editor of Memo Review.