Janenne Eaton, Evidence - a stratigraphy

Amelia Winata

An art critic is overcome with equal parts smugness and shame in the event of discovering an artist who had been under their nose the whole time. I had one such encounter last Saturday, when, as a Brunswick flâneur, I wandered up Moreland Road’s narrow, overgrown footpath to Haydens, where I came face to face with Janenne Eaton’s paintings for the first time. At face value, this may sound normal enough, except that Eaton is in her seventies and has had a decades long career showing in some of the best-known Australian galleries and institutions.

When I visit Haydens, it is the first day of Eaton’s exhibition Evidence—a stratigraphy, which presents twelve paintings completed between 2009 and 2022. The eponymous Hayden (Stewart) sits in his office, bemasked, having only recently overcome the Covid he picked up at David Eagan’s Neon Parc opening. To be sure, acquiring Covid at this event was perhaps the ultimate tick of inner-Melbourne art world belonging. If you didn’t get Covid at Dave Egan’s 2022 show, then where were you?

Eaton was in the gallery that day, chatting with visitors who were mostly acquaintances. When I arrive, she is in conversation with the artist Sam George. She has the vibe of your cool aunty who smokes, Vogues and sneaks you sips of wine when your mum’s not looking. She is wearing earrings that look like mini Inge King sculptures. A thick publication surveying her work, designed by former student Simon McGlinn, is on sale for fifteen dollars and Eaton has elected to donate all proceeds to the Hayden’s studios, having—according to one source—“left the accumulating phase of her life”. The catalogue is a testament to Eaton’s achievements through a long career and the relationships she has built along the way.

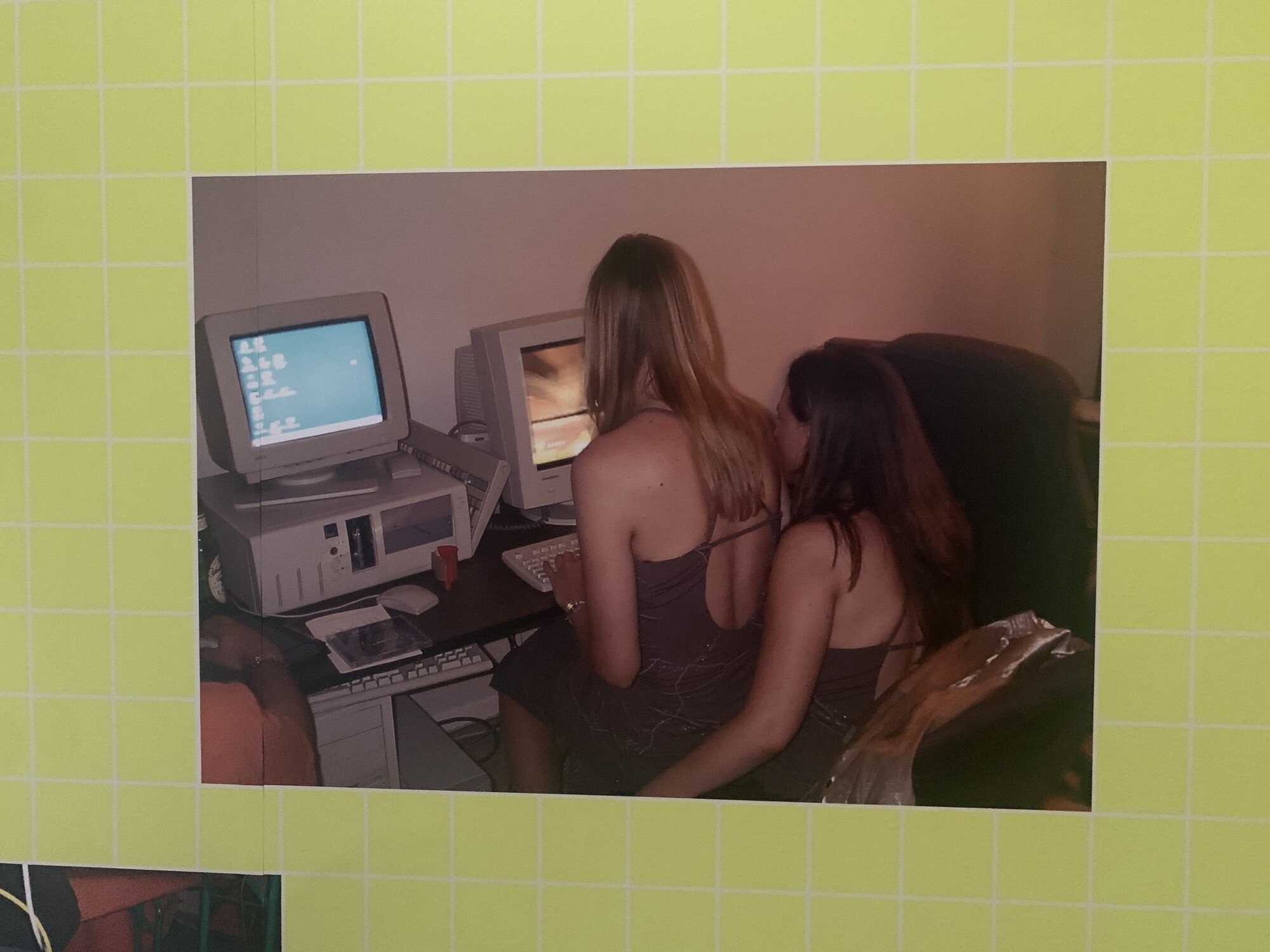

And, indeed, this is the paradox of Eaton, who is a known and beloved quantity in many circles, yet relatively under-appreciated in a younger set. She was the Head of Painting at VCA from 1999 to 2011, and before that had taught at VCA from 1992. Her students included many of Melbourne’s most influential artists: in addition to McGlinn, there was Sam George, Damiano Bertoli, George Cue, Lucina Lane, Rohan Schwartz, Nick Selenitsch and Lisa Radford. She maintains friendships with many of these former students, who remember her pedagogical generosity. Radford recalls that Eaton purchased an analogue video editing machine for the painting department in the ’90s so students could make video work. Tail between my legs, I conducted informal surveys throughout the week to ascertain who of my art world acquaintances knew Eaton. Very few did. It’s fantastic that the Hayden’s showcase is bringing her to new audiences. If the work in Evidence—a stratigraphy is anything to go by, Eaton’s is a compelling practice.

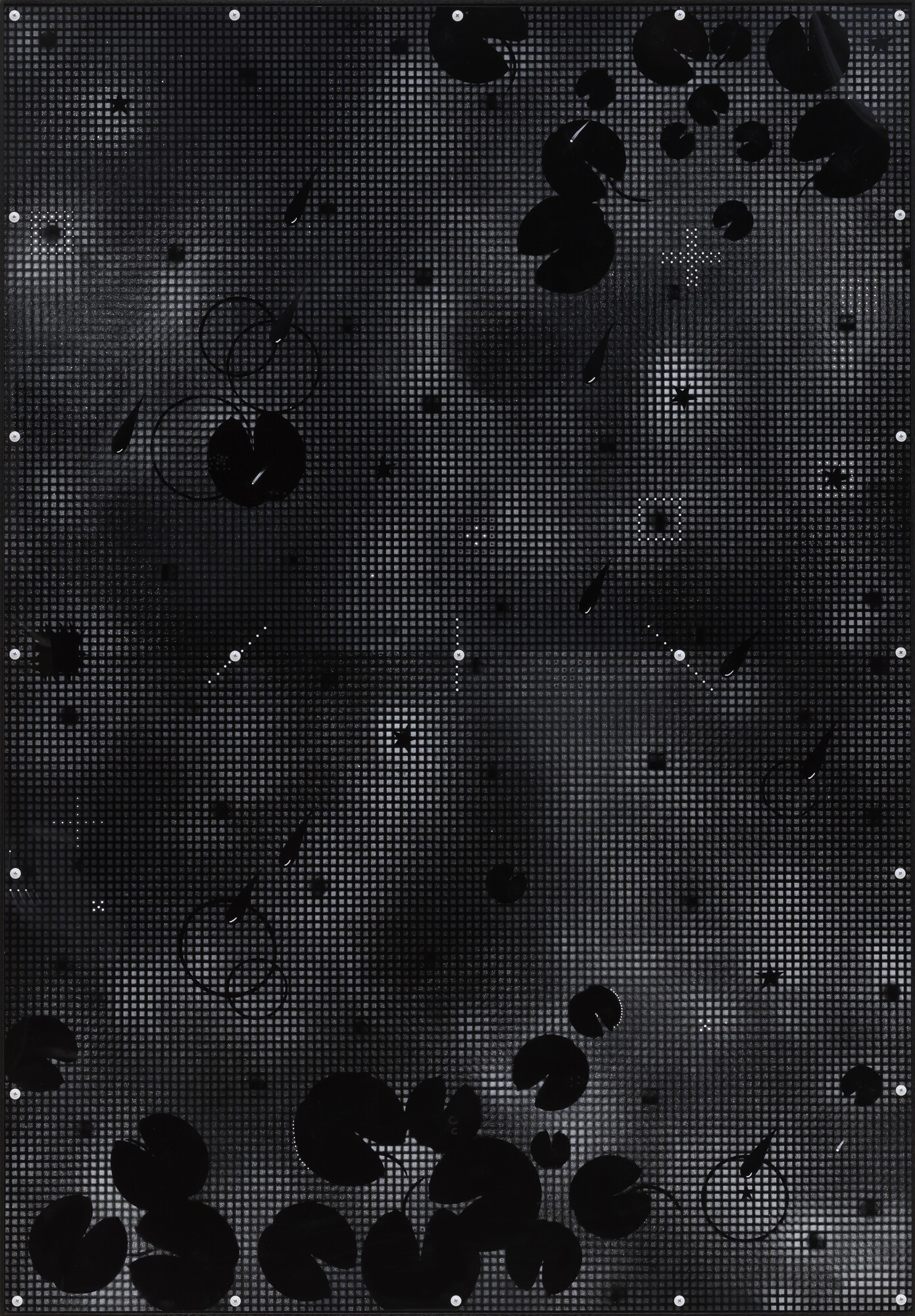

In the 1970s, Eaton dabbled in figuration, but she has consistently worked in abstraction since the 1980s. Although these works on display were mostly made in the last decade, a latent post-modern sensibility is evident. There are whiffs of the bold, graphic letters of Rose Nolan, the geometric compositions of Peter Tyndall and the all-over patterns of Vivienne Binns. It is not to say that these artists were necessarily Eaton’s peers, but simply that Eaton came up around the times (I accept Binns is older, Nolan is younger) and displays a post-modern je ne sais quoi. Take, for example, Windows on the universe—the lily pond (2018). It’s an oil painting of small lilypad silhouettes with an almost cyanotype quality on a tightly gridded backdrop that is mottled through—an effect likely created by Eaton’s use of spray paint. The tension between surface and the illusion of something beyond the grid is, in many respects, not dissimilar to Binns’ paintings, which also often have an all-over print logic.

It is interesting to compare her current work to a description by king of post-modernism Charles Green, published in 1991 in Artforum on the occasion of an Eaton exhibition at Tolarno. Of the 1989 painting Breaker, Green writes, “Black-on-black rectangles, edged in white, frame a central image in which the artist’s transcendental folds fade upward into a white void. Breaker is saved from the dual extremes of pomposity and preciousness by the artist’s handmade geometry”. Apprehending Eaton’s current body of works, little has changed in her methodology. She continues to focus on geometric, all-over patterning that is meticulously hand rendered. This is evident in Talisman for rain (2010), a small painting with a raindrop pattern on a gridded yellow backdrop. The drops have been painted in uniform repetition, giving the effect of a print. But upon closer inspection, Eaton’s hand becomes evident. The yellow reflection line in each drop betrays itself (only just) to have been applied, ever so carefully, by hand. I’m not sure what kind of “pompousness” Green had sought to find in Eaton’s Breaker way back in 1991, but I think I can agree with him that the presence of the hand—at least in Talisman for Rain—is a revelation.

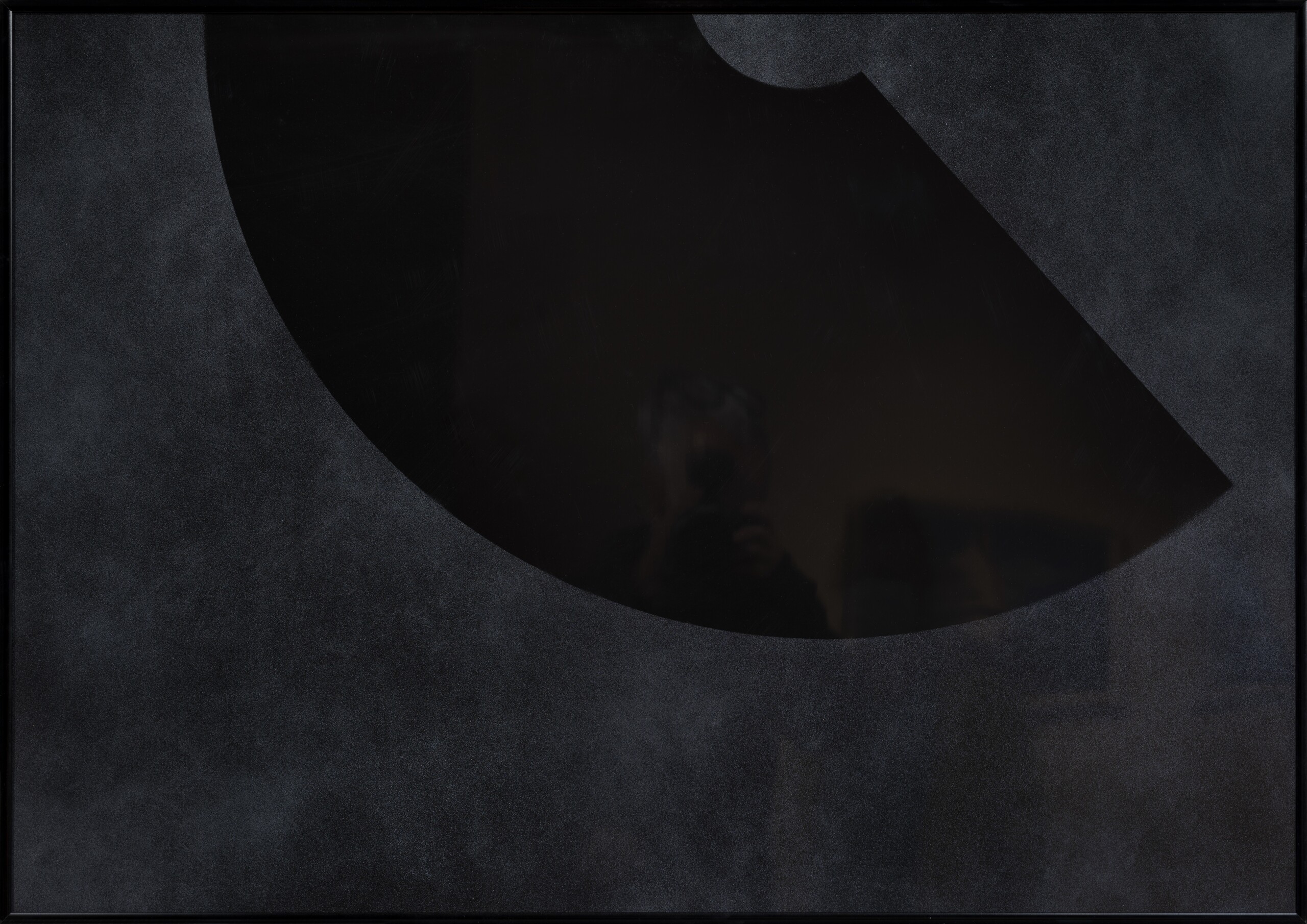

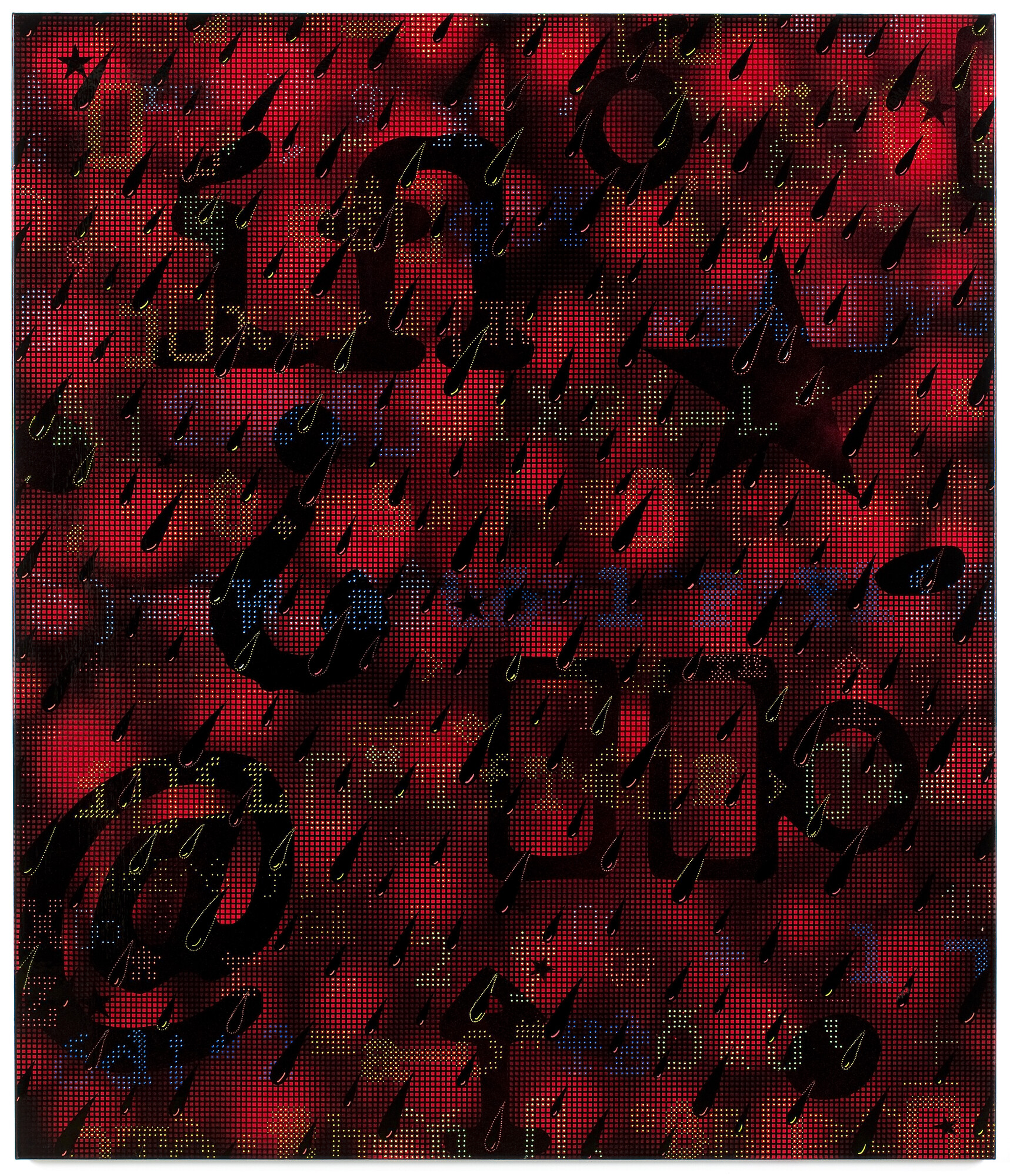

But if, as I have observed above, there remain similarities between Eaton’s current practice and hers in the 1980s and 90s, then it should also be said that this current body of work avoids the pitfalls of stale postmodernism. Indeed, in the aforementioned Viv Binns-ian Windows on the universe—the lily pond, Eaton had dotted the edge of the picture surface with screws, a display of her nuances that sit outside of any tradition. She is, as Radford takes pains to emphasise, “punk”. Eaton has also largely swapped canvas for HIPS—high impact polystyrene—a shiny plastic base that creates a reflective picture surface. The HIPS reflects the viewer back onto themselves and the metaphor of the black mirror abounds. In Rear vision—all things must pass (2020) the viewer sees themselves in a jet-black space that I belatedly understood to represent the clearing made by a windscreen wiper. I was too busy taking a photo of my reflection in the work. Eaton’s use of dots, too, is less Ben-Day and more digital algorithm. See, for instance, Code for a new chromatic dream (2009), a pulsating screen of red with indecipherable text applied over the top.

In the room sheet, the use of archaeology as a framing mechanism for Evidence—a stratigraphy is initially quite confusing to me. Archaeology suggests something in the past. A fossil, a relic. Eaton’s consideration of archaeology to frame the present—the, uh, Anthropocene (sorry)—was an odd choice perhaps. It makes more sense when considering the exhibition as a cross-section of her practice over time. Although, as I note, developments in Eaton’s practice have been quite minor. Her style has remained quite consistent, though her subject matter has perhaps now shifted towards the present digital age. As the room sheet states, her works “highlight how a virtual language of sign systems mediates our day-to-day experience of the tangible world”. Highlight is the correct way to consider this relationship to the digital. And in this sense maybe, yes, Eaton’s consideration of the present day is archaeological in approach, insofar as she doesn’t scrutinise, critique or shake her fist at those damn kids who refuse to get their heads out of their screens. Her approach is to observe and interpret.

Sam George tells me that people used to look at Eaton’s work and think it was created by a man, but now they look at it and think it is created by a younger person. I imagine which works in Evidence might have once been slapped with the unfortunate masculine label. There is plenty of black. Is this the stuff of dudes? Borderlands (2019) is a multi-panel, black painting with a skull that has been cut down the middle and inverted. Sculls and black = bro-town? Maybe. Borderlands was, in fact, first exhibited at Buxton Contemporary in a collection exhibition called National Anthem, which reflected on Australian national identity. As separate essays by Kate Just and George Criddle in Eaton’s survey catalogue suggest, the work engages with questions of belonging and, specifically, the ongoing humanitarian crisis surrounding Australia’s treatment of refugees. The pattern painted onto the work is that of a chain link face—a symbol of refugee detention. The masc approach to this topic might very well have been to ignore it altogether, or for Eaton to insert herself into the narrative—à la Quilty.

The accusation of youthfulness is slightly more palatable than that of hypermasculinity. Three black paintings are hung in the smaller entrance gallery. In one of them, Save the frosts (2022), Eaton has used rhinestones to create crosses and to adorn some stars. Eaton’s kitsch use of rhinestones immediately reminds me of the millennial Spencer Lai. George responds to my proposition with a reversal: “You could in fact say…Spencer Lai’s rhinestones are very Janenne Eaton”. Touché. To my knowledge Lai was not a student of Eaton’s. But if we were to flip the script, we might see Eaton in the black and textured paintings of Rohan Schwartz, or the grid formation that was an important backbone of Damiano Bertoli’s ongoing project Continuous Moment.

The moral of George’s inversion is, of course, that Eaton’s influence is everywhere, even if I—the ignorant critic—was not aware of Eaton until recently. Her legacy is strong in the work of artists who she taught in her decades at VCA and in the work of a new generation of artists influenced by those artists. And, by the same token, she is an artist who has cultivated her own whole practice while helping to cultivate that of her students. I’ve been telling people about her all week, as though her work were some fantastic secret I am now privy to. But a secret so many people already knew.

Amelia Winata is a Narrm/Melbourne-based arts writer and PhD candidate in Art History at the University of Melbourne.