Richard Mosse: Broken Spectre

Damien Laing

You arrive at the screening Broken Spectre by the New York-based Irish artist Richard Mosse by passing through the cheerfully rearranged twentieth-century Western art on the NGV’s third floor. Avoiding the Judd cube and if you’re lucky glancing left instead and seeing Sarah Lucas’ tits in Self Portrait with Fried Eggs (1996) on the far wall, you enter Broken Spectre with the aural invitation of Ben Frost’s unnz unnz soundtrack. The frequency of our state gallery’s display of Mosse’s work in solo-exhibition (The Enclave in 2015, and Incoming in 2017) has robbed it somewhat of the force of its pomp, as has the comparable technical brilliance of LUME, Melbourne’s moving art light-show (currently showing Monet and Friends, adults $44), but take a seat in a bean bag and get ready to be impressed.

In there, five separate projectors combine on the screen in the twenty-metre wide room, creating a 32:9 double anamorphic visual plane. Grainy black and white 35mm film, is cut, overlaid, and juxtaposed with iridescent ultraviolet and multispectral images demonstrating Mosse’s ocular mastery. For over an hour and a quarter, and with a surprisingly identifiable narrative structure, Mosse is showing us what’s going on in the Amazon. Initially I thought the work’s title was a reference to the opening lines of The Communist Manifesto (1848), “a spectre is haunting Europe—the spectre of communism”, the political import of which was totally perplexing to me. But as a recovering failed Heidegger-bro I looked to the etymology of spectre and realised that along with ghost or apparition, it is of course the root of spectrum—by which Mosse appears to be saying things fall apart; the centre cannot hold. My friend Simon later informs me of the Brockengespenst, or Brocken spectre phenomenon named after the Harz mountains, where the observer’s body is captured between the light source (usually the sun) and a clouded field before them, producing an ethereal rainbow lens-flare that surrounds their shadow. In any case Mosse, undaunted, gathers light with his ultraviolet, infrared, multispectral cameras, an attempt at ocular totality.

Like a surprising number of residents of Melbourne’s wettest then stickiest summer, I took refuge on a Saturday, making myself comfortable enough to fall asleep while the planet burned on the screen. With dazzling brilliance, the film weaves together deforestation, mining, Indigenous activism and beef production with such mastery that the message is partially undercut by the awe and sensory exhaustion Mosse creates with his recurring crew. They are the aforementioned sound artist Ben Frost; Trevor Tweeten on cinematography; the real unspoken hero film developer Matthew Warren, who hand developed all the infrared film; and spectronomy engineer Jeffrey Carson, who engineered the special cameras.

We begin with an Apocalypse Now (1979) tracking shot of dead trees shifted to neon in water that, for me, recalled dancing to MY DISCO at Lake Mountain with trees burnt in the Black Saturday bushfires (2009) lit up blood red. For the audio, Frost gives his best Hans Zimmer impression on a soundtrack that is haunted by the call of a whale-like earth moaning and turns from Berlin techno to Villa-Lobos guitar lines, as well as diegetic insect sounds that are recorded ultrasonically to accompany the often ultraviolent imagery. Mosse’s vocabulary of images includes tracking aerial shots that sparkle with brockens, mechanical processes, big trees being chopped down, macro images of life in the undergrowth, controlled burns, mining, dredgers appearing out of the water, tourists, cows, etc. The layering and juxtaposition of scenes is carried over in the dynamic use of recording technology—the cameras. The film is bookended by a political coda, sweeping shots of protests in Brasília and an impassioned speech from the young Yanomami activist Adneia, which appears to be delivered directly and solely to the camera and by extension us in the audience. The ongoing dynamism of this politics is recalled in the events in Brasília on 8 January, which are also evidence of the interchangeability of politics like the exchange of products. Almost to the day of the anniversary of the US Congress attack, with murkier dynamics for this observer, bolsonarista stormed Oscar Niemeyer’s sleek answer to Walter Burley Griffins’ beautiful Canberra. The architecture critic Kate Wagner glibly remarked on the internet’s public square that it was perhaps the first time the use of this public space in the renders had come to life. Following Adenia’s speech, the film ends with scenes of indigenous activists protesting in the streets of Brasília—not every protest makes the news.

Mosse’s career so far has been a story of approaching conflict through an emblematic technology of representation and using this technology against itself. Where The Enclave used Kodak’s infrared aerochrome film stockin Congo, and Incoming had military hotspot cameras to interrogate the Frontex refugee crisis in Europe, Broken Spectre develops Mosse’s practice by overlaying these image-capturing technologies: infrared black and white film, digital ultraviolet, and an ingeniously self-made multispectral video camera at a range of scales from the cadastral down to the domestic and to the microscopic teeming with more-than-human life. Put more simply, Mosse’s work attempts to face the biggest challenges we have created here on earth. He is quoted in the catalogue as saying: “You need to put the thing in front of the lens. You have to be present in the space with the thing”. When the thing is the deleterious effects of globalisation you come up right against the limits of representation. And the quote continues to reveal the challenge of the task: “When the thing is an abstraction far bigger than human perception, it’s very difficult to do so adequately”. Mosse, in his attempt to show this thing in itself, must reproach himself. With its authoritative scale, the panoramic mega-screen that is his preferred method of display is both gently and then forcefully interrogated.

Whilst disclaimers come in the form of foregrounded images of power, and their terraformed reification, the pretty lens-flare brockens denaturalise and self-aestheticise the work. At times, there is a narrative nearness to the genre of the Western, and I found myself caught out laughing alone during the beautiful sequence of Fazendeiros cowboys bouncing on their horses through the most clear-field paddock, where burnt tree trunks stand in for Quixote’s wind turbines. It is a moment of gracious absurdity in a very austere film. Yet Mosse’s attempts at self-criticism are most evident in the inclusion of Adneia’s speech, which begins haltingly and rises to a fury as the constructed appearance of the situation is dissolved by the pure emotion in their demand for something to be done. A reproach directed at the artist and viewer for action greater than taking or consuming images. As her voice rises, the sequence breaks as the reel of film runs out, the viewer is notified through subtitles, the audio recording continues and intensifies, and when the camera is reloaded the image is returned and the split of eye and gaze is there again.

As the film progresses, I grew impatient of the sweeping scenes of globalisation’s destruction, of territorialisation by the fencing of land into fields, of pointless deforestation—perhaps a cut to a scene of a mildly happy family at some suburban McDonalds almost anywhere in the world tucking into their happy meals—but this doesn’t have to be in the same room. Martin Parr’s Common Sense 76 (1997) sits in the antechamber to this work; it is a gauche quadriptych of consumerism glistening with the synthetic second nature we’ve created for ourselves. In realising the aim of implicating the viewer, I also wonder with all the technologies of representation at the curious scarceness of smartphones in the film—after all, the gold mines that are clearing the forest are printing the circuits for our and everyone’s devices. Save for one sequence, I was disappointed not to see people, Indigenous and settler, mediating their experiences with the same technology the audience carries, as in the work of the Karrabing Film Collective, for example. There are limits to what a film that already takes in so much can embody and no doubt a phone camera would break with the aesthetic tone of the film - but the big budget choices have the effect of distancing the audience.

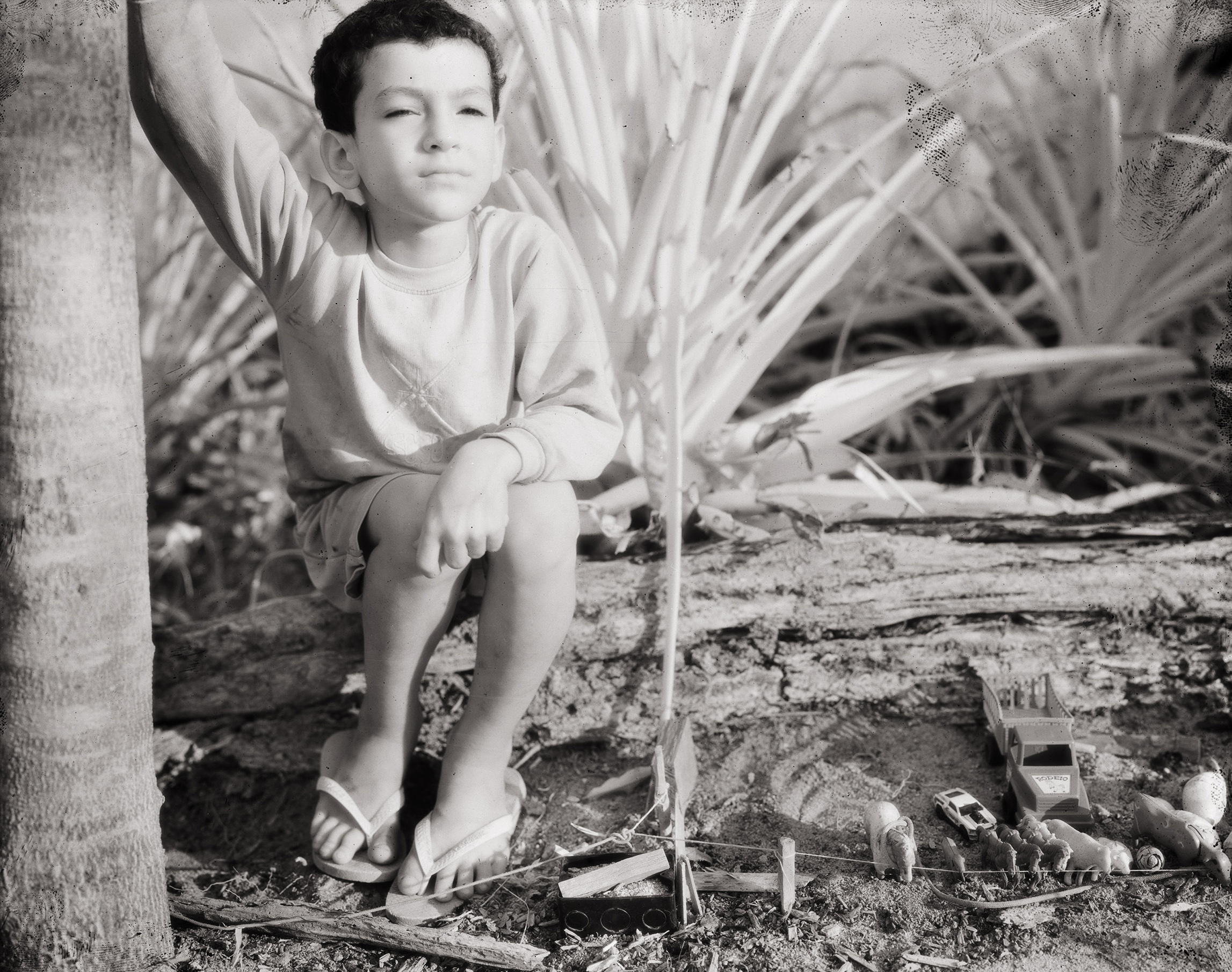

This is seen in the use of punchy, inky film alongside other high-tech imagery. For sure, it displaces a simple linear time of the film, the time of the now. But, there is also a consequence to the beauty of Kodak Eastman and its cinematic quality—showing destruction in a richer medium than the daily news has the effect of cutting the protagonists from our lifeworld. An example of Mosse’s play with temporality is a sequence featuring a family: a child plays with plastic cows lassoing the small figurines as his family prepares a meal; this is directly followed by a team of men back-burning forest, whose wet fecundity requires several attempts to be successfully cleared. The pathos of a stringed guitar is overcome by the loud crackling and roaring of fire as our identification with the cute rural family is tested and the viewer twigs that the picturesque village and family have built their lives, just like we have, on burning lapsarian forests.

I increasingly feel that the NGV is underappreciated. Busier than Chadstone, it holds a significant place for so many people, and as side-eyed as I can be about an exhibition on Alexander McQueen the fact that NGV has co-produced a film of this ambition is a formidable achievement. I hope the commissioning of works such as Broken Spectre demonstrates a commitment to artist films and space will be made for exhibiting and collecting daring local filmmaking too, films like David Easteal’s The Plains (2022), sitting comfortably alongside international heavy-hitters like Mosse or Tekla Aslanishvili’s A State in a State (2022). The NGV’s support of resident artist Mosse over a ten-year period and with three long-term projects is just as laudable as it is completely opaque.

For Broken Spectre, the story is that Mosse was so exhausted after confronting the refugee crisis depicted by Incoming that he decided to take it easy and take pretty plant photos in the Amazon. As sharp a thinker as Mosse is (educated at Goldsmiths and Yale), the project quickly became a series of stills he titled Triste Tropiques (2021), which he created using a multispectral camera. The images work as maps, with elements of the image quantified and made visible in a technology known as GIS (geographic information systems). Mosse’s sparkly counter maps of the Amazon and its degradation are far sexier than the ones I myself see every day at work as an urban planner, watching over the remnant grasslands of the western basalt plains as they are eaten by house and land packages. Mosse plays with cleverness in a self-aware reference to Levi-Strauss’ triste memoir of fieldwork in South America. Stumbling onto such a rich and ambiguous conflict, so representative and central to the issues facing all of humanity, Mosse spent three years with his boys in the Amazon, flying helicopters and drones, and bringing the work together—all for it to be brought to Naarm. It remains peculiar, however, that the very system that Mosse critiques, globalisation as extractive and productive,resource his commissions. Mosse, a celtic tiger ensconced in the New York art world, is well-equipped enough to work in Brazil and show the outcomes concurrently in Melbourne, London and Portland.

In the week before I viewed the work, I was about a one-hour drive away in Toolangi State Forest, on Taungurung and Wurundjeri Land, looking for greater gliders with mostly boomer activists from Extinction Rebellion and other aligned groups. We were trying to find the endangered marsupials to help halt the NGV’s sister institution, VicForests, from clearing old growth, native, and sacred trees. Using my consumer grade camera, I tried to capture the honey glow of the glider’s eyes. Looking at the sophistication of Mosse’s aerial shots and thinking of the famous “weapon” camera from Incoming, I wondered if Mosse really had to fly his fixed wing plane so far to uncover globalisation’s deep stain on the landscape, and to make an art engagé such as that interrogated as recently as late last year on this website, by my esteemed colleague Philip Brophy. But, like Mosse, I too try to retain a “sense of faith in the importance of the documentary image, the evidential image.” In our context, with a colonial state that explicitly proclaimed terra nullius and the countless continuing fault lines of extractivism that propagate from that worldview, the thing still needs to be shown. I for one am certainly looking forward to the NGV’s commissioners sending Mosse to the Murray-Darling next time.

Damien Laing is an urban planner and member of Artist Film Workshop. With thanks to Kelvin, Liss, Giles, Freg, Simon, and Ella for the help.