Triennial

Giles Fielke

Buried within the question recently explored by Felicity D. Scott, ‘Who is the festival for?’, is the rapidly fading possibility of a public. It is a discourse that seems to slip too easily into arguments about the centrist compromise of regulated-, or neo-liberal, architectures of the state. The elaborate zones of exclusion raised for the National Gallery of Victoria’s inaugural Triennial, which follows its first International Festival of Photography, seem to point only toward one social imaginary: some of us—increasingly fewer of us—play the citizens. Others fall outside of the law, into a radically precarious and simultaneously emancipatory statelessness, a barbaric expanse coveted, nevertheless, by those searching for another world.

Revisiting the rise of art’s festivilisation, Charles Green and Anthony Gardner describe a scene in the foyer of the Sydney Opera House during the first Biennale of Sydney in 1973, where a relatively small, ‘insular and conservative,’ selection of mostly Australian art peered out cautiously toward the horizon of international contemporaneity. A few lines later they state that by its third edition in 1979, the Biennale had become, for its founders, ‘Australia’s lifeline’ to the outside art world. Fast forward nearly half a century, to the NGVs globally oriented Triennial—which all but replaces the local focus of 2013’s Melbourne Now—and it appears not much has changed. Very much keyed to the promotion of its founders, principally the NGV’s current director Tony Elwood, the exhibition is not about the multitude of artworks on display. Instead, it proposes that we, the lucky few, should get lost amongst this ‘free’ survey of global contemporary art and design in a comprehensive experience.

This dizzying escapism brings together a random selection of names with minimal exhibition design featuring some known artists, others not so well. Ultimately, however, the Triennial leaves us to marvel at the lack of a grand narrative for the exhibition. Not even the five categories—movement, change, body, time, and virtual—frame anything more than bookmarked sections in the exhibition’s massive catalogue. The festival struggles to say something more than the leanest generalities. Here is art for public consumption. Here is new art acquired for the public collection. What public? I ask myself this as I navigate the Manusian aesthetic of Ratellack Thompson and Other Architects’ geotextile work Garden wall (2017). It is a commission by the NGV and, among others, the curiously named Golden Age Group. For me its white, sectioned corridors can only recall the images of offshore detention centres such as I’d just seen in the dissident film Chauka when it screened at ACMI.

Perhaps more so than its East Coast competitors—Brisbane’s Asia Pacific Triennial, and the aforementioned Sydney Biennale—Triennial is aimed unapologetically at consumption. The consumption of contemporary culture, of discrete images (no less than twenty seven items are listed for sale on the front page of the expo’s website). Unsurprisingly, Triennial has already weathered its own Transfield-lite artist controversy. Wilson Security, who currently holds the contract for the NGVs security, became a target for three of the 100 local and international participating artists who felt the need to signal their awareness of the continuing despotism of Australia’s Strong Borders security policy, the execution of which includes the Government outsourcing to private companies such as Wilson. Three artists renamed or adjusted their works at the last minute. Wilson Must Go, the question remains, to where? The twisted logic of the corporate-state insists there is no longer any outside, that we are all complicit.

This sentiment feeds the overarching sense I get as I wander for hours toward the endlessly dissolving fringes of the Triennial—that the main cost of globalisation has been public agency, that alternatives to the status quo are too easily co-opted. This idea of the public owes to the idea of the nation-state, of course, but here is an outsourced, privatised, and commercialised public space that is sold back to the public at a profit. In the third floor ‘NGV Triennial Bar and Lounge’ a bottle of water costs $4.70. The permanent collection is blended and folded into this contemporary re-arrangement of tastes, smells, furniture, clothing, bodies. Even if it hasn’t yet been captured, the cognitive labour required to participate in this exhibition stretches the usual definition of the museum to its limits. We do not so much participate in the event, or the celebration of global transculturation, as we do enter an experiment in the future organisation and control of people through these plastic corridors, allured by the spectacle of ‘the crossing’ itself. We feel compelled to produce selfies, an apt rubric for the fragmentation of identity. This experimental edge to Triennial seems geared towards the reproduction of the national (gallery) as the lap-dog of a corporate, transnational network of world-picturing oligarch-aspirants.

Sound paranoid? Follow me. Adam Linder (b. 1983 Australia) offers a work that quite literally p(l)ays the artist for scrubbing clean the ossification of concrete culture in his Choreographic cleaning service no. 1 (2013). Like Marina Abramovic’s earlier performance work, Cleaning the Mirror (1995), Linder understands contemporary art as aimed at exfoliation. Cleaning up after the mess. The mess here is globalisation, now seen as an embarrassment to those who’ve come up trumps.

Rafael Lozano-Hemmer (b. 1967 Mexico) invites visitors to participate in a live-action composite portrait for his renamed work Wilson Must Go (2017), one that I read as revisiting, with no real critical insight, the pseudo-science of Sir Francis Galton’s nineteenth-century typographic phrenology. It is this kind of spectacle that marks the entire expo, making it feel like the Herald Sun’s one-dimensional takes on the city’s recent ramming attacks—it directs you to be thankful for the existing authorities, and at the same time to fear the other. Cognitive dissonance makes many works very hard to engage with, everything has been violated by its curation. In many ways, therefore, Triennial is not a space for critical thinking. Any expectation of an educated, art-going, public has been sold out to a fun-for-the-kids model packaged as mass-marketing entertainment, to kidulthood.

Ron Mueck’s much commented-upon, oversized skulls look rushed and prop-like up close, and could represent each artist and designer in the Triennial. Like Xu Shen (b. 1977 China), commissioned to create a massive centrepiece for the foyer, the temporary installation of scaled-up sculpture looks much better in the press pictures than it does up close. It is easy to see past the initial impulse to the hasty execution of these works. Upstairs, games designer Tom Crago has installed an immersive VR system, Materials, in the top corner of the NGV galleries. Casually employing the word ‘mindfulness,’ this first-timer art work all the while neglects to mention that Crago is better known as a local patron of the arts. Here he takes up an opportunity to embed a commercially-minded project into a cultural space as a lesson in native marketing for the new museum.

Incoming (2014-7) by Richard Mosse (b. 1980 Ireland) is the work that perhaps best examines this shift to contemporary art’s aesthetics, and which now appears within the Triennial framework after its earlier commission by the NGV with the Barbican Art Gallery in London. This shift to contemporary art as the model for presence, immediacy and spectacle reaches fever pitch as we watch the results of thermal-imaging cameras seeking to reveal those beyond national borders. To be fair, these images are formally indistinguishable from those we are shown during the televised cricket’s KFC Hot Spot replays, which aims thermal-imaging cameras at the batsmen. Mosse, however, frames his work through the technology’s military application. The spectacularisation of human suffering—long the wellspring for Western representation—is so overt in Mosse’s imagery that it transcends the fair-like atmosphere of the Triennial. Any sense of reflection on this vision of the other is abandoned for its sensuousness. Incoming relies on our assumption that demonstration is enough. With nothing truly sectioning the Triennial’s general ‘world of art and design’ remit, the clinical smell of the galleries’ descent into darkness bites with its utopian/dystopian tenor. It cannot help but bring up the disparate reality of crises of blunt-force terror and pharmaceutical nihilism that works like Mosse’s only pretend to investigate; and for which the work’s emotional contents really lie.

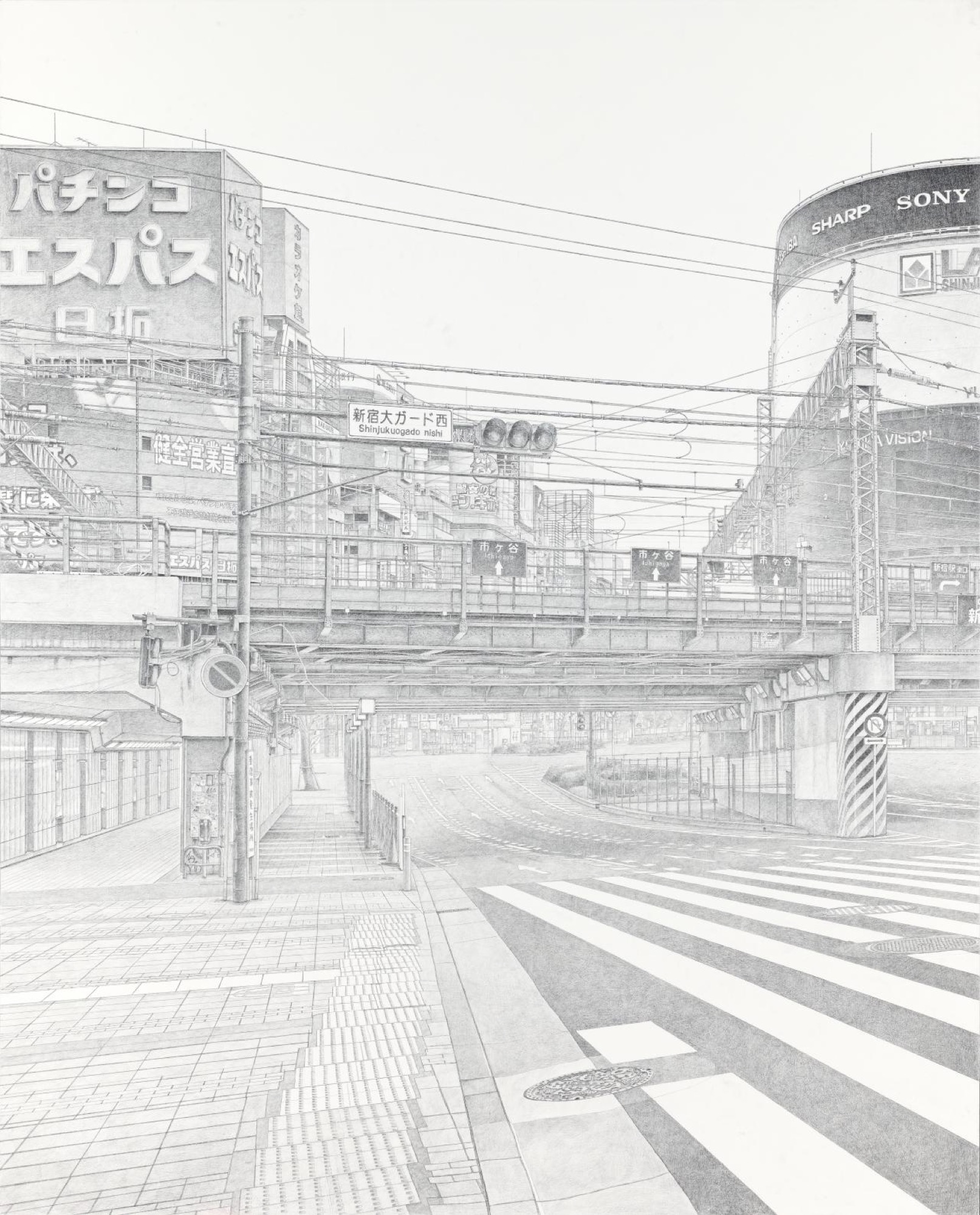

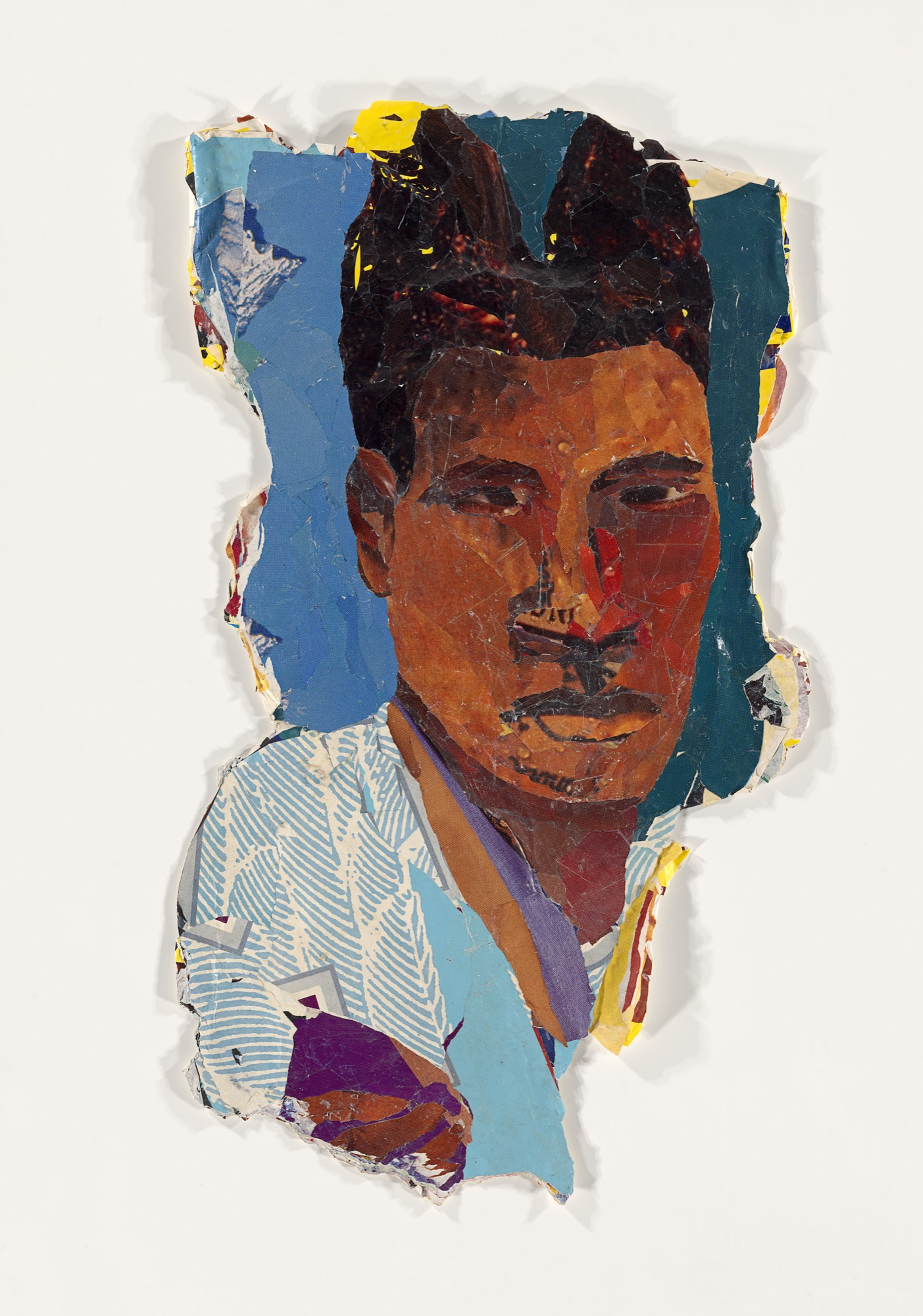

But it is not all bad. Kay Hassan (b. 1956 South Africa) shows a selection of torn collages that repurpose the gloss of slick media imagery across a gallery wall. Noss Noss Studios’ Hassan Hajjaj (b. 1964 Morocco) has filled the atrium with a pleasantly patterned colour scheme. Pae White (b 1963 United States) shows two massive ab-ex works of uncannily painterly woven tapestries. Yamagami Yukihiro (b 1976 Japan) contributes a beautifully subtle pencil and video hybrid wall work Shinjuku calling (2014). The subtle colour gradations recall anime images merging with slow cinema and for me is the most compelling work in the show. Even artist Hannah Black (b. 1981 United Kingdom), whose featured writing in the catalogue is compellingly reflexive, only succeeds in adding to the up-to-the-minute feel of the show. Elsewhere, Jonathon Owen (b. 1973 England) has a work which almost collapses in ignominy, his untitled reworking of a classical nineteenth-century marble statue collapses the nymphs torso, which has been brutally turned into the links of a chain. Nestled within the permanent collections, it is the most reductively symbolic work of Triennial. This blurring of the expo’s boundaries into the permanent collection is a marked exception to an idea that seems to work mainly in the other direction, expanding outwards to any momentarily noteworthy fad: Yayoi Kusama (b. 1928 Japan) for Ikea. Grey paint on cork. Kimoji’s. Instagram take-overs. Activated Spaces.

The bigger video installations—like Candice Breitz’s (b. 1972 South Africa) Wilson Must Go, which is so horrifically conceived I could barely watch it—and Mosse’s Incoming tend to rely on multi-channel immersion. This distinguishes the museum’s architectural amenities in the exhibition of video from conventional screen spaces, like online platforms for digital work such as Vdrome. The problem is that this quest for novelty means the video work is often not as good as other work that is readily available online, just more expansive, more indulgently lux. This grates with both Breitz’s and Mosse’s contents: stateless people in desperate situations turned into shallow spectacle. Alternatively, a recent work by Melbourne artist Oscar Miller comes to my mind. Any comparison of Miller with Mosse and Brietz may at first seem unfair. Here are artists commanding military-grade assets with conglomerate funding from multiple sources, versus an artist whose use of an already obsolete consumer electronics camera produces a David and Goliath type confrontation. Yet I still found in Miller’s work the best use of video I’ve seen all year. Miller’s short video work, Flowers for Lucy, was exhibited through the online platform recess, curated by Kate Meakin, Olivia Koh and Nina Gilbert. Mosse, on the other hand, has created a seductively expensive work that is hard to miss at the Triennial and sums up for me what lies at its crux: scale replaces idea.

The NGV has devised an exhibition space not so much for artworks as for the spectacle of the festival’s elitism. In this case, built as it is on the topical issue of stateless people, the Triennial feels oddly devoid of empathy. Images of people who are perhaps, through the rosiest of lenses, a coming community of emancipated subjectivities are in a more sober light the wretched of the earth. What Ariella Azouley would call photography’s ‘civic negotiations’ are transgressed in Mosse’s use of the camera-weapon. How do you seek clearance permission from people who have no protection. But it cannot be denied that here also lies the expo’s popular appeal. The demonstration of a technology that renders visible the heat map of surfaces, living or dead, from a safe distance (alternatively 30.3kms or 50kms, depending on which part of the wall text you believe), is kind of like watching the cricket through the KFC Hot Spot replay.

Like Ben Quilty’s truly hopeless oil painting of a life jacket, High tide mark (2016), the works have been acquired by the NGV purely for their status as commodity containers. In Quilty’s case, the sense is that painting still carries with it historical markers of value—thickly applied and excessively opulent in oils—it is like Tiger Airway’s marketing of a queue-jumper feature for cheap trips to Bali. In Breitz’s work, for its encoding of star power—Alec Baldwin and Julianne Moore—to make a political work that falls so tastelessly flat that it’s only redeeming quality can be found in the fact that it ultimately reads as an experimentally speculative attempt to gauge the potency of contemporary art as such. A work titled Wilson Must Go, featuring asylum seekers, protected by contracted security, propped up by A-list actors, helps to prove the lie of the artwork as serving anything other than the status quo.

The abstraction of images of suffering at a such a distance, like the heat-reading telescopic camera to which Mosse had been given access, therefore makes the question of why the military would give an artist access to a piece of state of the art equipment. Let alone one that is classed as a weapon. Besides a ‘boys with their toys’ reading of the work, the most important question to reflect on is this fact. Is propaganda, soft power, diplomacy, the public, even relevant here anymore? The official war artist is the contemporary artist–in our case the aforementioned Charles Green–one who can sensitively introduce the barbarism of the present. The metaphorical proximity that theatres of war have to the art festival is another reason for my suspicion that this is all an exercise in an Adam Curtis episode exploring the new normal: divisive discourse and networked authoritarianism.

Gardner also recently revisited the year 1955 as an auspicious for the rise of contemporary art. It is the year of documenta’s first survey exhibition in Kassel, and also coincides with the opening of Disneyland in Anaheim. It is with this image that we enter a truly ‘global’ moment, one perhaps also defined by Simone de Beauvoir during her visit to the Forbidden City in October 1955. In Beijing for the 6th Anniversary of the Founding of the Communist Party in China it appeared the city, the east, was neither new nor original. Here was an anachronistic image of state power. This is also, as Alexander Nagel and Christopher Wood have argued, a complementary definition of what contemporary art is: state-power that is no longer the power of the nation state. This is its corporate principality.

Finally, the utter decadence of the Triennial as a celebration of contemporary art, against the cultivated background of inequality, abuse of power, and injustices now reported around the world daily, seems determined to predict a pre-revolutionary moment. Let them eat cake. This, of course, is the name of an annual New Years Day party that is located at Melbourne’s Werribee Mansion. Tacitly condoned drug-fuelled drum-and-bass orgies are scheduled to take place in close proximity to exotic wildlife transported to colonial Australia. It would be a damning image if it wasn’t so absurdly hard to believe. This is the model for the festival, and it happens every year, right under our noses. Happy holidays.

Giles Fielke is a writer and musician working at Monash University and the University of Melbourne. He is the Business Manager of the AAANZ.

Title image: Richard Mosse, Incoming, (2015–16), three channel black and white high definition video, surround sound, 52 min 10 sec (looped).)