Altona Homestead

Daniel Kotsimbos

I am sitting in a room. I am looking at an electromagnetic ghost-hunting device delicately placed beside a Baby Born doll garbed in a Victorian nightgown. It is close to midnight on a Saturday, and I am with a small investigative team of mostly middle-aged women whom I have only just met. Last week, I completed an online form and paid an eighty-one-dollar fee to participate in this paranormal investigation of what is reputed to be one of Victoria’s most haunted buildings, the Altona Homestead. But it is my first time inside the building after being struck by its modest bluestone construction when I sought shade under last year’s runner up Victorian Tree of the Year, an enormous Moreton Bay Fig in the adjacent Logan Reserve.

The Altona Homestead offers these extended paranormal investigations on the first Saturday of each month (and Devonshire tea on the first Sunday). During my Saturday-night investigation, I was given an old laminated A4 document listing the spirits said to frequent the house and the types of hauntings to expect. The document mentioned historical figures connected with the homestead, including its 1840s colonial instigators, Alfred and Sarah Langhorne; a 1900s solicitor and subsequent owner, William Crocker; and post-World War I occupant Lloyd Vaughn associated with the bathtub haunting. Other ghosts included Rose from the front bedroom and a young boy from the nursery cupboard. These presences highlight how the homestead engages with its history, whatever that history might entail. After all, history isn’t just a record of what has happened; it is also a curated presentation of the past that can sometimes return to haunt us.

The colonial origin of the Altona Homestead is all too familiar. In January 1841, on the unceded lands of the Yalukit-willam people of Boonwurrung Country, Alfred Langhorne squatted on an area eighteen kilometres south-west of Melbourne, paced out a two kilometre rectangular block, marked it so that the allotment aligned with the cardinal points of the compass, and organised for a homestead to be constructed facing the sea. In Edward Northwood’s Langhorne Brothers as Overlanders and Merchants, the receipts for the initial order of homestead supplies from Launceston are recounted. These include four-thousand metres of timber, nine kegs of white lead, a case of sheep shears, forty bags of flour, four horses, six casks of apples, two bales of blankets, a weighing machine, and forty cases of liquor. With such an order, and on land depicted by the Robert Hoddle survey as “good open flat grass plains,” Alfred Langhorne operated the homestead as a grazier.

At the beginning, Alfred had teamed with one of his five brothers, Charles Langhorne, to run a cattle drive between South Australia and Victoria to feed a booming Melbourne settlement that was only six years old. Their business drove through the Central Murray River region, staking a segment of the Rufus River to operate Langhorne’s Ferry moving cattle between states. In June 1841, while the foundations of the homestead were being laid, the Langhorne business was involved in violent altercations with the local Mauraura people while attempting to cross the river, resulting in numerous deaths on both sides and plundered stock. In August 1841, in response to the events at Langhorne’s Ferry, an official South Australian police expedition travelled to the site and murdered forty Aboriginal people in what became known as the Rufus River Massacre. Langhorne’s eventual holding is roughly what we now call the suburb of Altona.

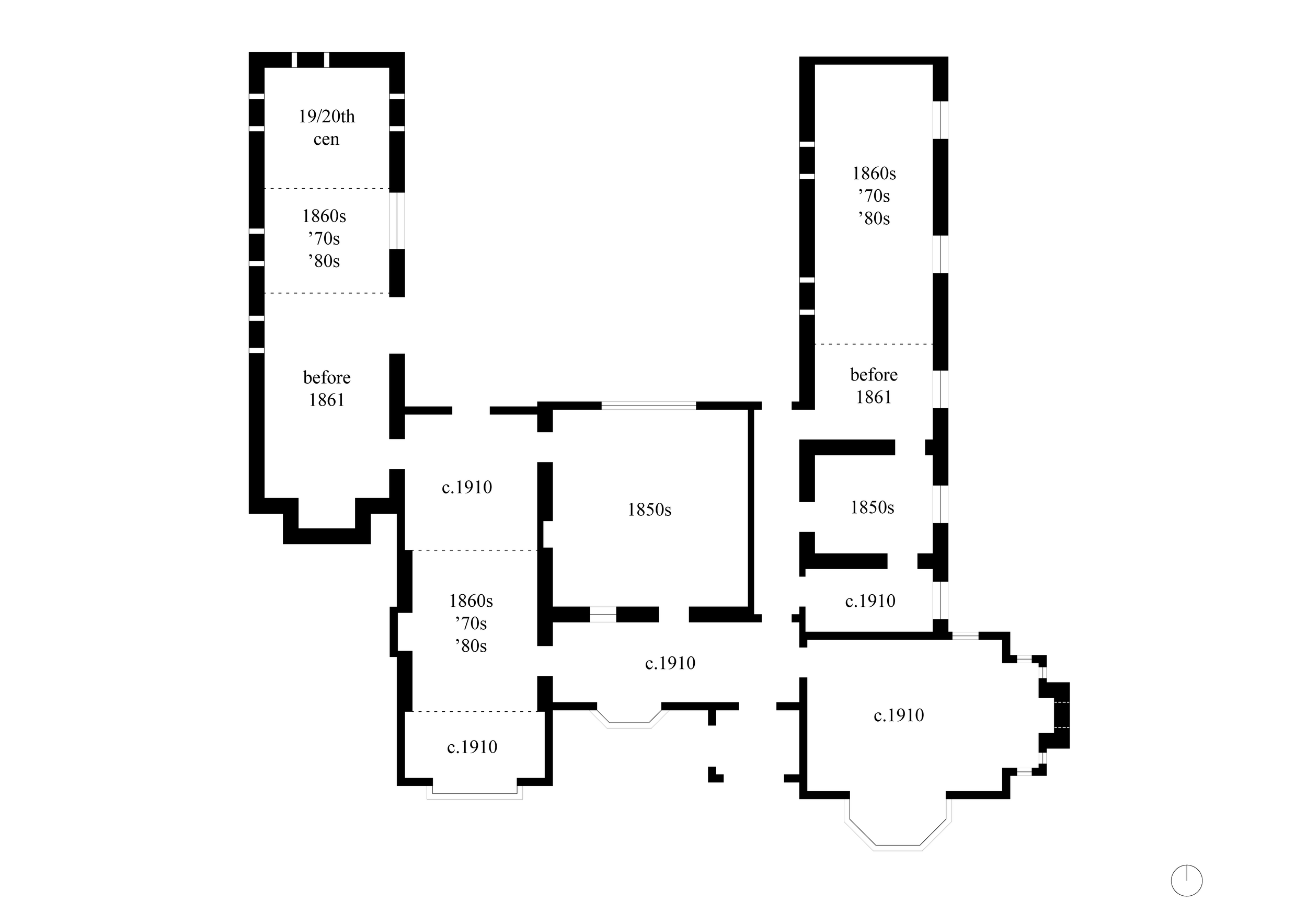

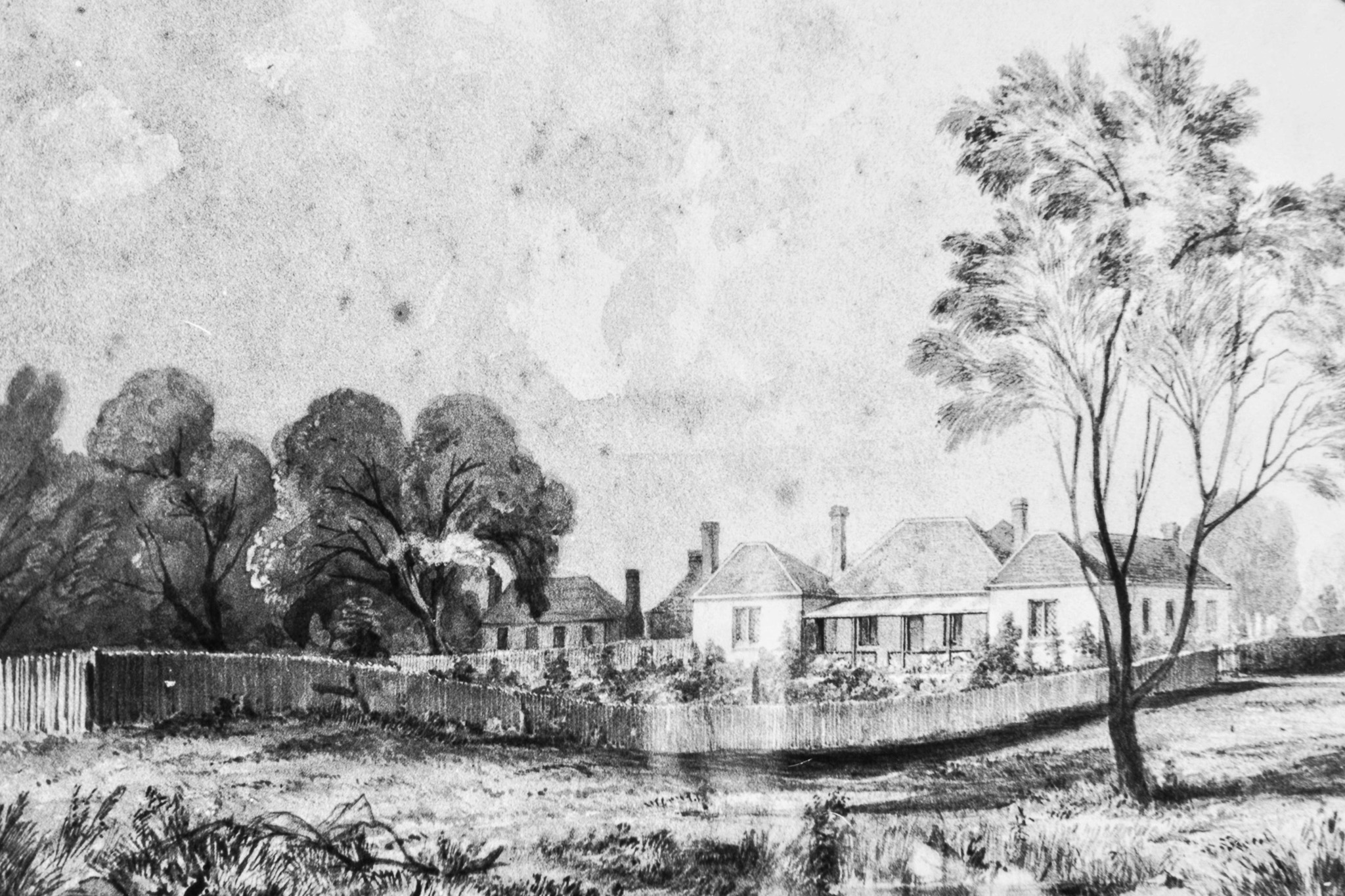

Today, the Altona Homestead is a u-shaped building comprising a central dining room facing south towards Altona Beach with two projecting wings, bedrooms in the east, and service rooms in the west. The central dining room and two wings are constructed primarily from bluestone and date to the late 1850s. The house was initially built from timber in 1841 before being entirely rebuilt with bluestone as a precautionary measure following the events of the Black Thursday Bushfires of 1851, when a quarter of Victoria burned. In the 1900s, almost as if placing a giant pair of scuba goggles on the building, a red brick bay-windowed facade was added.

Always “occupied,” the homestead has perpetually changed hands on the speculative market, being sold and leased to families throughout the late 1880s to the 1920s, where it then had a brief period leased as inexpensive holiday accommodation for local workers. Organised by the City of Altona in 1988, a conservation analysis was undertaken by architectural historian David Bick. These records provide some insight into the significance of the building, its original form and growth. The records also show that when used as holiday accommodation in the 1920s, decommissioned tramcars were converted into bungalows, each with their own plumbing, spread across the front yard of what is now Logan Reserve. Too costly to run, the tramcar bungalows were disposed of, and the property was acquired by the council in the 1930s, which continued to lease it out as a private residence until the building was eventually reconfigured into Municipal Offices in 1957, marking the last drastic reconfiguration of the building. The 1950s additions gutted portions of the original foundations and confined the 1860s structure within an asbestos-ridden council office conversion, complete with a suspended beige grid of acoustic panels. Since 1963, the homestead has housed the local camera club, a children’s dentist, and then Altona Laverton Historical Society, which today maintain it as a “house museum.”

Sleep deprived, searching for ghost orbs, and hoping to understand the “spirit” of the place, I noticed that the house is fully furnished with objects that date from the 1950s back to the times of lead and mercury furniture. None of the furniture is original to the house itself, with most pieces being donated over time by the local community. Other than being vaguely “old,” the furnishings do not appear to clearly belong to any specific period, if you look closely . The interiors therefore give an impression of what the homestead may have looked like during the various periods it has been occupied, all at once.

One of the objects I came across was an Italian mandolin dating back to 1870. It is a loaned item that seems to have no relevance to the homestead, other than that both came into existence at roughly the same time. The mandolin was a thematic addition to a pianola, a miniature children’s piano, an adult pump organ, and a taxidermied hummingbird display, all situated across each corner of the same room. From different eras spanning some thirty years, these examples of furnished history are positioned (or rather stored) in an eerie attempt at historical reanimation. A member of the Historical Society confirmed that the homestead won’t be accepting any more piano donations.

The building has inevitably changed over time. In the bay-windowed front drawing room there is a framed picture depicting the homestead. I used a flickering battery-operated candle that was in the fireplace to shine enough light on the picture to make out a watercolour drawing of the drawing room from the outside. Undated, and in a pastel palette, it depicted the homestead with a centrally placed front door in lieu of the current fireplace from where I had just taken the candle. I later learned that this is a post-1960s council portrait. The current fireplace in the drawing room is a 1980s restoration of a door conversion on what was the original fireplace, that was really only original to the 1900s brick facade addition of the 1850s bluestone homestead, which was a rebuilding of the initial 1841 timber structure. Glued to the wall in the hallway, a brass plaque reads, “Altona Homestead Restoration Project: this building was officially reopened to the public on June 18, 1989.” There is a certain irony in removing a door in order to reopen a building.

The vague “oldness” of the Altona Homestead distances it from possible readings of contemporary domesticity. The paranormal investigations and Devonshire teas reinforce this; it’s as if one were playing dress-up in order to please the building. In saying all of this, we find the homestead in a condition where it seems it can exist today only based on a “past” that it is now defining for itself. This explains why over the course of a hundred or so years, a fireplace was constructed, turned into a door, and then turned into a fireplace again. The ghosts on the laminated A4 sheet are the actual inhabitants of this building, and it is not a coincidence that most of them were “original” when the fireplace was “original.” Perhaps there is something more to take away from that enormous tree I sought shade under. For at the same time as the construction of the first fireplace, a seed was planted in the front garden, and the Moreton Bay Fig keeps growing.

Daniel Kotsimbos is a recent graduate of architecture and contributing editor of Memo Architecture.