Kim Gordon’s Body Part 1: The Body

Kim Gordon’s rock-star body is an object of projection—vacuuming, sleeping, wielding a Jazzmaster in Airbnb limbo. From Sonic Youth to No Home Record, she performs middle-class blankness, but what’s staged, what’s real, and who’s the audience for her disembodied domestic rebellion?

Memo presents a sneak peek of issue 2 with the first part of Audrey Schmidt’s two-part article, “Kim Gordon’s Body.” Part 2 will appear in print, shipping late July. Preorder here.

Contemporary dance discourse can be boiled down to a rather rudimentary concept: “The Body.” It is the definite article that defines a discipline. The X Body (the virtual body, the performative body, the gendered body, the collective body); The Body as a site of Y (production, decolonisation, lived experience, difference, resistance); The Body as Z (subject-agent, object, document, archive, image, screen). Spice it up with a few other lexical mainstays like embodiment, disembodiment, bodies in space, corporeality, gesture, distantiation, mediation; or, for a little philosophical jazz, The Body without Organs. Whichever way you approach the equation, contemporary dance is tediously and unavoidably preoccupied with The Body.

Kim Gordon’s survey Object of Projection at the Substation, is all about “the Body.” The media release gave prominence to a “special presentation” of Proposal for a Dance (2012), a triptych video installation featuring “two female performers wielding electric guitars and wearing Rodarte dresses.” The marketing copy describes their “experimental choreography” as “a gesture towards anti-pop ideals and their implications for the female body.” But the hero image recalls another familiar variable: The Celebrity Body. It is a still from Picture Window (2022), a video work made with Manuela Dalle, featuring Gordon “sleeping” with a Fender Jazzmaster (AKA “the hero of the underground”) draped across her body. She is lying on her side under a Swiss military wool blanket in a room with all the “neutral” and depersonalised signifiers of an Airbnb.

Gordon revisits here a figure of the sleeping artist that has been endlessly rehashed by artists since Chris Burden’s Bed Piece (1972): Susan Hiller’s Dream Mapping (1974), Bruce Gilchrist’s Divided by Resistance (1996), Marina Abramović’s The House with the Ocean View (2002), Emilia Telese’s Life of a Star and Sleepwalking (2005), Chajana denHarder’s Sleep (2012), Taras Polataiko’s Sleeping Beauty (2012), and Zhou Jie’s 36 Days (2014). These performances centre on the gap between the phenomenal (lived) and semiotic (interpreted) body by way of “problematising” the spectacle with the vulnerable non-performance of sleep.

The trope is quite popular among celebrities whose semiotic bodies are the exemplary products for public consumption. Perhaps the most influential example of the sleeping celebrity is Tilda Swinton’s 1995 performance work at Serpentine Gallery in London, The Maybe. For seven days, eight hours a day, Swinton slept in a raised glass vitrine in the gallery with up to twenty-five-thousand voyeurs. She was exhibited alongside installations by renowned artist Cornelia Parker made up of celebrity memorabilia from London collections such as the half-smoked cigar of Winston Churchill, Queen Victoria’s stocking, and Napoleon’s rosary. In Lady Gaga’s 2012 Sleeping with Gaga, coinciding with the launch of her inky new perfume “Fame,” the pop star “slept” in a giant replica of her eau de parfum bottle, allowing partygoers to reach in and touch her hand. She closed the performance by posting iPad portraits on Instagram, getting a tattoo, and getting naked.

Gordon’s take on the “celebrity body as public object” was probably best expressed in her 1993 catalogue essay “Is It My Body?” written for Mike Kelley: Catholic Tastes at the Whitney Museum of Art. She writes about Kelley’s stuffed animal portraits Ahh … Youth!, one of which appeared on the cover of Sonic Youth’s Dirty album the year prior, likening them to rock stars — as “something to be projected upon.” She writes, “the body’s not theirs anymore, it’s a public domain and public perception.” The Rock Star Body is the Object of Projection.

As described, Proposal for a Dance was all about the Rock Star Body. Gordon and her niece Eleanor Erdman make some nasty noise on electric guitars in nice Rodarte dresses. The duo also wears little pink, studded fingerless gloves and poke guitar necks as they enter the crowd tightly packed into the Berlin club. Just outside the three-wall installation was a print-out, Proposal for a Dance (score) (2023), a narration of rock-star stage movements written with male pronouns: “he moved his arm in an arc making a windmill motion.” The same text was exhibited in her first survey at White Columns in 2013 as Guitar Performance text.

Rock stars have always been linked to masculinity for Gordon, something she wants to embody. In her memoir Girl in a Band (2015), Gordon says her desire to be “inside that male dynamic” is the reason she joined a band. The realisation came after publishing “Trash Drugs and Male Bonding” in Real Life magazine in 1980, which she credits for granting her “an identity in the downtown community.” Forty-four years later, the same desire surfaces in her studio album The Collective, a title she took from Jennifer Egan’s book The Candy House, which centres on tech that allows you to experience another person’s memories and emotions in exchange for the sale of your own consciousness. The song “I’m a Man” sees Gordon embody an out-of-work college dropout feeling sorry for himself: “You got a degree (I’m a man) / I’m just a fucking slob (I’m a man).”

It would be too easy to accuse Gordon of simply “putting a dancer on it” — the classic criticism of out-of-ideas artists who need a little extra entertainment at their openings to get the champagne sipped. Gordon is a multidisciplinary artist with a long history in the world of “expanded dance.” She is old friends with Jutta Koether and describes performance art luminary Dan Graham as her NYC mentor. It was Graham who encouraged her to write her downtown debut piece for Real Life, and she wrote one of his obituaries published in Texte zur Kunst. Even next-gen Erdman is a Graham fan who performed a work about Martha and Dan Graham’s late ’70s punk shows, Two Grahams, in 2007 at Reena Spaulings. In fact, Gordon is so deeply indebted to Graham’s ethnographic approach to rock stars, subcultural ideals, and suburbia that a quick glance at his collection of essays between 1965 and 1990, Rock My Religion (1993), illuminates the conceptual underpinnings of Gordon’s entire oeuvre. You just have to dig past Alice Cooper to discover Kim Gordon’s body.

In Picture Window, the domestic rock goddess vacuums and rinses the bathtub, all with the Jazzmaster hanging flaccid at hip height. There is no dialogue, just the diegetic sound of the amplified guitar as it clashes with the fridge door or cutlery drawer and reverberates about the staged domestic scene. Towards the end, Gordon makes a supermarket-magazine-ready sandwich and salad, eating it in awkward silence with her daughter, the poet, actress, and model Coco Gordon Moore. They are recognisably themselves, but they lack “personality”; they go about their pleasant, pretty, and idle days on autopilot, weighed down only by Gordon’s underground accessorising. At the Substation, Picture Window is played on a loop with 12341 Branford St. Sun Valley (2022), in which Gordon walks around a wrecking yard ethereally rubbing her amplified phallus on the exoskeletons of car carcasses. When Picture Window starts back up, it’s as though “it was all a dream.”

Gordon claims to take inspiration not from Gaga or Swinton, but Chantal Akerman’s 1975 feminist film Jeanne Dielman, 23 quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles, a minimalist drama chronicling three days in the life of a widowed homemaker trying to put food on the table for her child. Although Gordon is a well-to-do divorcee, not a tormented widower, Picture Window is missing all of the “hysteria” and violence of Akerman. On day two, Dielman (played by Delphine Seyrig) begins to “malfunction,” skips a button, overcooks the potatoes; on day three, she stabs a post-coitus john to death with a pair of scissors. The finale of Picture Window sees Gordon flop down on the carpet she just vacuumed, as though for another nap.

The pace and generally awkward performances in Picture Window recall the “narrative” introductions to pornographic films. Dialogue is relatively unimportant, probably improvised, constructed entirely to optimise the tease. She vacuums the same area multiple times and holds the shower head in the bath a little too long. In the pornographic version, after pretending to clean the bath, there would be a climax. Akerman aside, art is typically less inclined to climax. Picture Window is more like The Sims, a kind of “second life” that appeals to a different libido. There’s something other than the housewife or the rock star that Gordon wants to be inside.

It’s a good life

I am delicious

Delicious

Air BnB, ah

— Kim Gordon, “Air BnB” (2019)

Gordon has regularly expressed an interest in “real-estate porn.” In 2014, she told Artforum that the interest stems from “the idea of staging the house” as seen in reality-TV shows like Flip or Flop. Since the late 1970s, Gordon’s “staging the home” alias, Design Office, crafted the illusion of a home improvement corporation. The first interior design interventions made by Gordon were in the private homes of friends such as Graham, and culminated in an exhibition at White Columns in 1981, Furniture Arranged for the Home or Office, which included chairs from different people’s homes. Design Office was revived in 2013 for Gordon’s first retrospective, also at White Columns, cited in the by-line for the films in this exhibition.

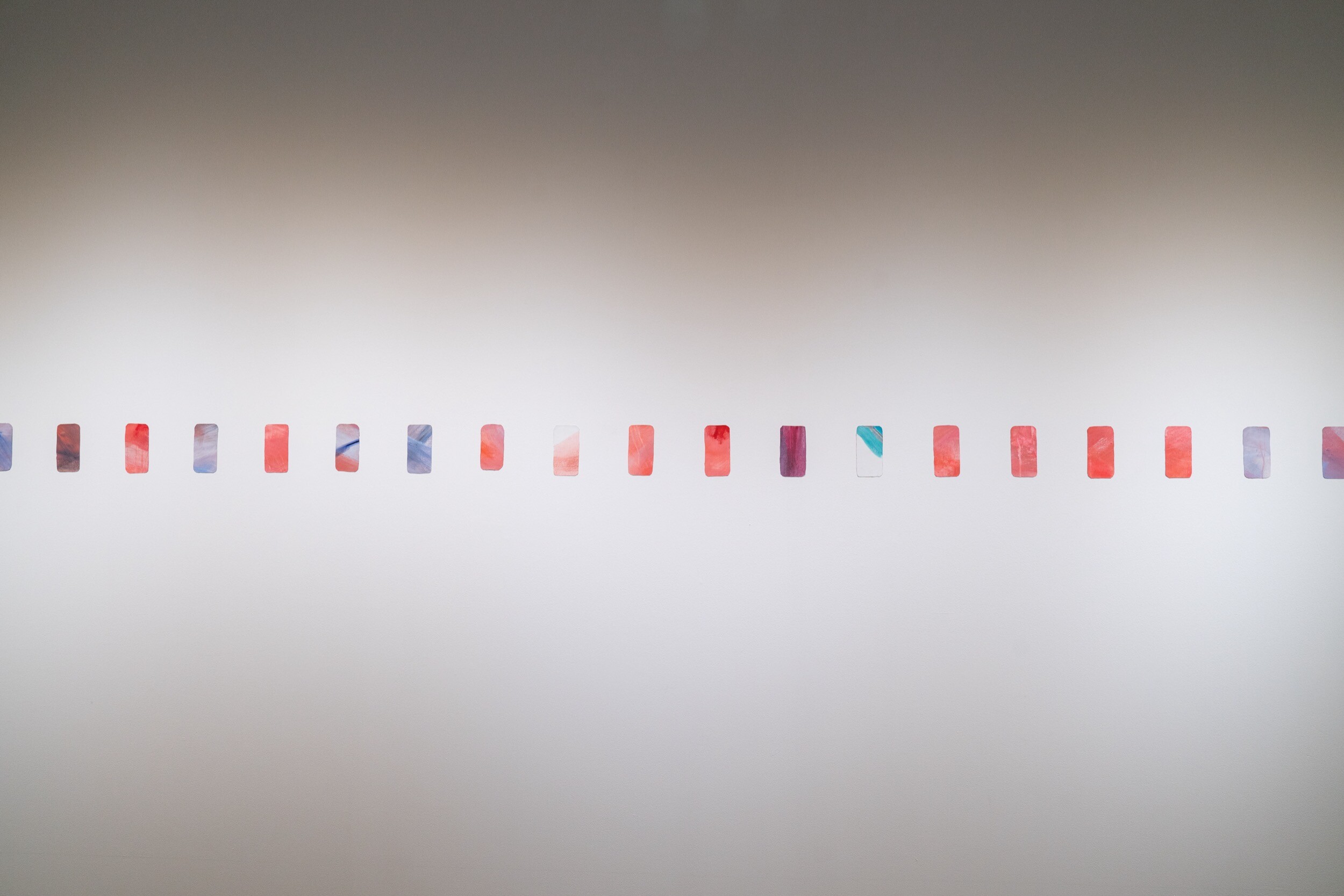

Nowadays, Gordon’s interest in staging the house is oriented more toward Airbnb signifiers. Her debut solo album No Home Record (2019) features a song called “Air BnB” (inspired by Chantal Akerman’s 2015 documentary No Home Movie). Airbnb is also the title of a series of tasteful, “decorative” drawings of female nudes Gordon exhibited at the Irish Museum of Modern Art in 2019. The non-video offerings in Object of Projection could likewise belong in the pantheon of Airbnb décor: iPhone-shaped canvases daubed with pastel paint so tepid they might as well be wallpaper and big mirrors with a muted black wreath design — art so unobtrusive it practically evaporates into the walls.

We get to the kernel of Gordon’s interest in “staging the home” in the final chapter of Girl in a Band. Here, she describes escaping her “huge, three-floor house” in New York to a hilltop Airbnb in Echo Park, free of “McMansions or wall-to-wall office buildings.” Shortly after this passage, she writes that she wanted to give Coco the most normal, middle-class life possible. As a holiday or escape, Airbnb’s “Belong Anywhere” blandness is also an “object of projection.” A middle-of-the-road, middle-class, live, laugh, love blank canvas that anyone can inhabit. From the dead-end dude of “I’m a Man” to Chantal Akerman’s housewife, the bodies that Gordon wants to inhabit these days have something else in common.

When Sonic Youth started out in the 1980s, Gordon admits, “all I was trying to do was dumb down my middle-class look by messing with my hair” and “to lose any and all associations with my middle-class West LA appearance and femininity.” In fact, being middle class is a recurring theme in Girl in a Band. She laments that the English punk scene (which was very much a product of the class system) saw Sonic Youth as “a bunch of middle-class brats who probably lived in lofts right above art galleries, who were putting on an act that wasn’t real, wasn’t authentic, wasn’t earned.” And to be fair, Sonic Youth did cop a bit of criticism for being, as Ray Brassier put it in a conversation with Mark Fisher, “vaguely bohemian / arty middle-class urban professionals,” or as Fisher called it, “avant-conservatism.”

Of course, Kim Gordon is no longer middle class. In the US, she’s on the lower end of the 1%. As it turns out, Picture Window’s setting looks much the same as one of Gordon’s real homes in Franklin Hills, Los Angeles, so perhaps the interior design and performances are more authentically staged than the Airbnb obsession might suggest. While her immersion in the honest world of the middle classes may spill over into real life (after all, it’s rooted in her upbringing), her creative endeavours generally aim a little lower. Take the “Sketch Artist” music video from No Home Record, where Gordon morphs into a ride-share driver, or the #MeToo-inspired “Hungry Baby” clip.

“Hungry Baby” is directed by Clara Balzary (Californian photographer and filmmaker with a client list that ranges from Apple and Amazon to Eckhaus Latta and Gucci, and daughter of Red Hot Chili Peppers bassist Flea). It opens with Moore in uniform for a building supply store in the suburban Los Angeles neighbourhood of Tujunga (Gordon told Dazed that the neighbourhood has a bit of a Republican / Trump supporter population, and she’s more one to bake a cake for Bernie Sanders). Moore is listlessly scraping a discreet little cluster of used gum off the brick wall in the car park when a tattooed man screeches up in some sort of pristine exhaust-heavy muscle car and asks, “You hungry baby?” He throws his milkshake at her feet and speeds off before Kim Gordon, playing the role of manager, comes out and says in the OG monotone vocal fry: “Cleanup in Aisle 9.” Well, that tips the minimum wage version of Moore over the edge. In a cathartic release of the downtrodden, she puts her EarPods in and erupts in contemporary dance improv to the generic post-punk bassline of her momager’s song. Even if Moore is “a creative with a social conscience” and has a desire to “uplift minority voices” (as Oyster magazine described her), there’s something about watching intergenerational rock-royalty pretending to work in a supermarket that doesn’t hit home.

________

In Part Two: Dogtown, Eckhaus Latta’s “conservative cool,” irony, postmodern curatorialism, graduating from the underground, and more. Available in issue 2. Order here.

Related

Monash University’s indefinite postponement this week of an exhibition featuring Khaled Sabsabi signals a deepening crisis in Australia’s cultural institutions. In the wake of Creative Australia’s Venice Biennale reversal, we are witnessing a damaging institutional retreat from risk—where the language of care and consultation masks a quiet erosion of artistic and academic freedom.