Does collaboration have a future?

Whether collaboration has a “future” raises a deeper question as to how collaboration can stake a claim on the future as such.

Today, the idea of artistic autonomy is constrained by a compulsion to collaborate. For me, whether collaboration has a “future” raises a deeper question as to how collaboration can stake a claim on the future as such. This question arises due to the burden of “the present,” which introduces contemporary context and responsibility to the role an artist plays in society. The artist remains accountable and tethered to the present, even when they stray from the pack and perform mitosis.

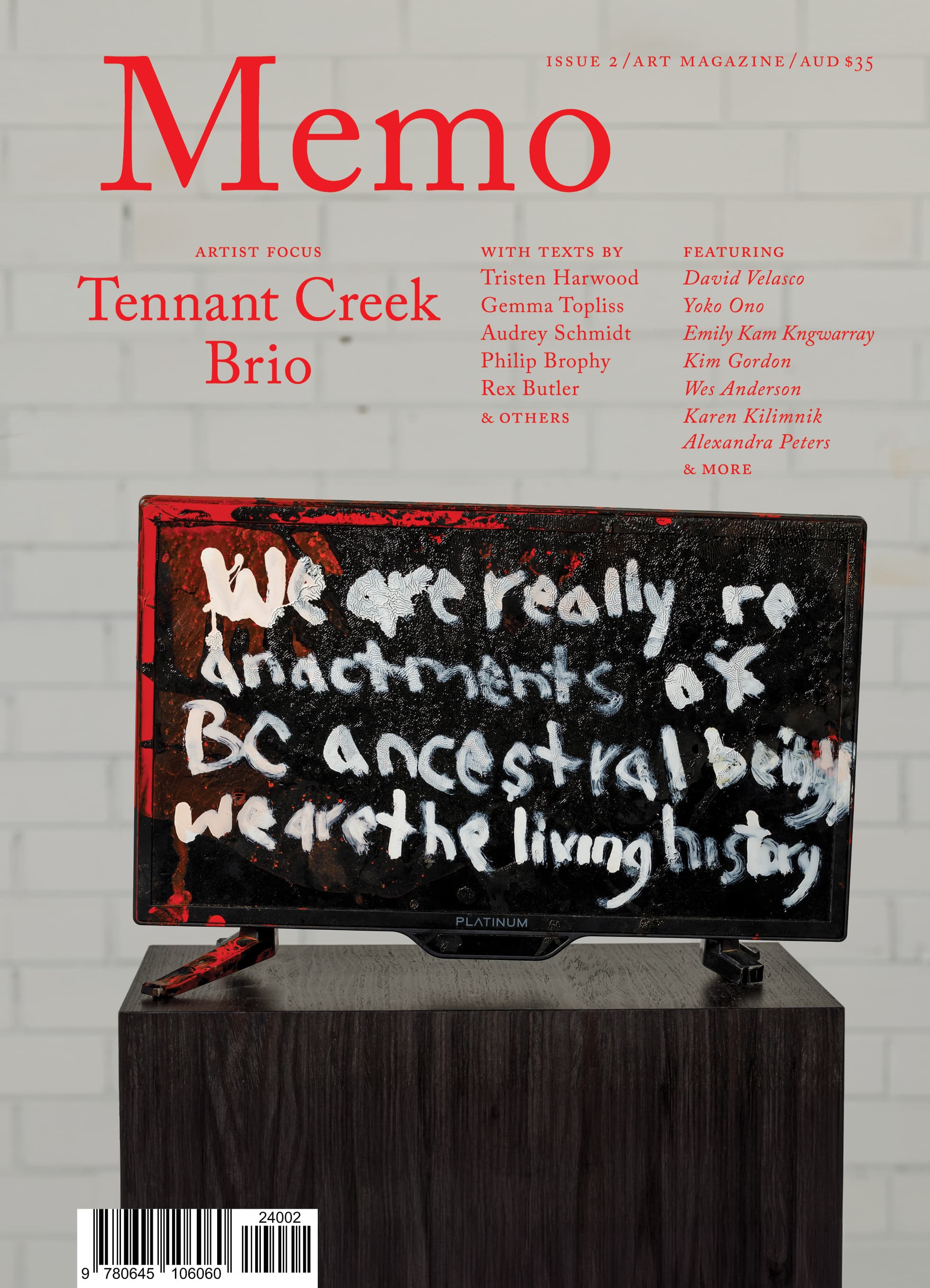

Exclusive to the Magazine

Does collaboration have a future? by Paul Boyé is featured in full in Issue 2 of Memo magazine.

Get your hands on the print edition through our online shop or save up to 20% and get free domestic shipping with a subscription.