Visitors in Yayoi Kusama’s The Obliteration Room, 2002-present, the Kusama for Kids exhibition at NGV International, Melbourne until 21 April 2025.© YAYOI KUSAMA. Photo:Tom Ross

Yayoi Kusama

Philip Brophy

Empathic critical bleating has surrounded Japanese artist Yayoi Kusama since her grande dame recuperation through early twenty-first-century ethical revisionism in the arts. It’s on full display in the dialectical corridors and image plastering that the NGV has perfected with its large-scale commissioning retrospectives that draw massive audiences. The institutional narrative of Kusama (an artist, yes, but realistically more a brand than an identity) takes the form of a Hollywood feel-good script: viewers champion the downtrodden, admire their resilience, and celebrate their hard-earned success. Choose your own humanist mythology to interpret Kusama’s current position: it will allow you to feel good about her, about art in general, and about you trying to comprehend what art is and why you should bother caring about it.

As has been the case with a string of lodestone Kusama surveys worldwide, the NGV hosts a psychic space for Kusama. She inhabits the NGV’s territorial zoning (its physical architecture, exhibition design, community outreach, media publicity, and creche activities) with all the theatrics of an “Occupy” performance. Art institutions now love to inflict this type of institutional occupancy on themselves in a public display of Munchausen syndrome while implying a facilitation of “institutional critique.” Kusama occupies the NGV zones in the same way she forges her famous “infinity rooms” as enclosures of occupancy. These “built environments” are truly vacuous spaces: immersive realms to snare a cynical public, who are charmed by the dumb childish wonder of being in a room of mirrors, reflecting and multiplying themselves so as to feel part of a cosmos constructed with all the flair of a Moomba show ride. If Kusama is a brand (as are all “startists”), she is prime fodder for the NGV (itself a brand more than a institution), which replicates Kusama’s dots so widely it feels that both she and the NGV are “infinite.”

But this review is here only to discuss Room 1 of the Kusama exhibition. For it is there in that occupied zone that Kusama’s perceptual practice and cultural contextualisation can be best appreciated, far from the din of the populist gawking that her art attracts.

Installation view of Yayoi Kusama’s Corpses, 1950, as part of the Yayoi Kusama exhibition at NGV International, Melbourne until 21 April 2025. ©YAYOI KUSAMA. Photo: Kate Shanasy

Yayoi Kusama, Accumulation of the Corpses (Prisoner Surrounded by the Curtain of Depersonalization), 1950. National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo © YAYOI KUSAMA

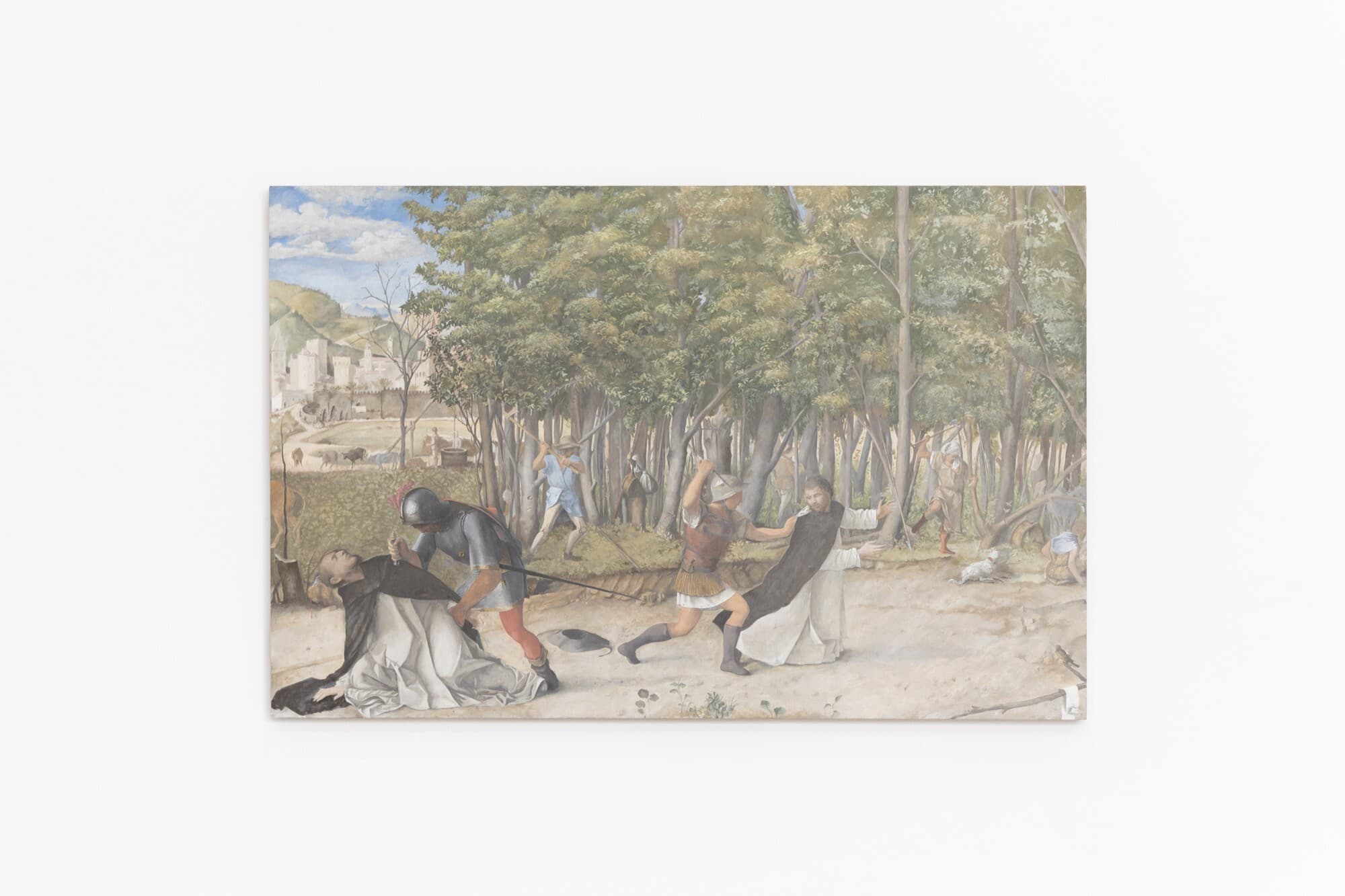

Room 1 covers Kusama’s experiments, projects and interventions from the early 1950s to the early 1970s. The first two oil paintings—Corpses and Accumulation of the Corpses (Prisoner Surrounded by the Curtain of Depersonalization) (both 1950)—are throbbing tentacles of dried-blood brown. They are painted as gory cartoons of abstraction not dissimilar to Okamoto Taro’s gaudy yet engaging meld of European Surrealist illustration and ancient Jomon iconography. Seemingly unresolved due to their illusionistic depiction (freeform braiding in the former; walls of a claustrophobic chamber in the latter), their feel for haptic form and destabilising space would become central to both Kusama’s psychological disposition and her designed environments. Yet, while solo surveys channel all evidence through the imaginary matrix of the controlling artist, these paintings are better understood as near impenetrable reflections on post-atomic affect in Japan. Taro—the template for Dali-esque self-promotion and media-baiting—exploited Modernism’s promotion of battlefield figures of destruction by repeatedly proclaiming since the 1970s “Geijutsu wa bakuhatsu da!” (“Art is an explosion!”) It is hard to find a post-war Japanese artist who does not complexly wrestle with the spectacular destructiveness of Modernist military metaphors, while silently acknowledging the US atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

The same year as Corpses, Toshi and Iri Maruki worked on the first three Hiroshima Panels, the first of which is titled Ghosts (1950). Radically fusing Japanese and European brush techniques and sensibilities, it realistically paints dying bodies with historical grandeur and post-human resonance, powerfully confronting the Adorno-esque impasse of how to render poetry after genocidal plans have been executed. Despite delivering a gouache abstract flowering in Atomic Bomb (1954, not in this exhibition but similar in style to a cluster of contemporaneous gouaches on display), Kusama chose to not be an ambassador for Japanese criticality afield. Throughout Modernism and beyond, Japanese artists have wished to be relieved of the burden of representing their nation—despite the world insisting on Oriental superficiality. Kusama chose an internationalist path followed by those in pursuit of empowering their voice within domains of power abroad. Taro’s generation targeted Paris; Kusama’s hit New York. There she opted to internalise teenage wartime trauma (numerous Japanese artists of diverse disposition did similarly), and concentrate on a personal journey that uncovered psychological schisms, while adhering to the romantic agony narrative of tortured artists beloved by gallery audiences. The Marukis, by comparison, saw their art as being at the service of historical reportage and social atonement—hence their comparative absence in an art world championing those ideals only when an artistic persona performs them. My laboured point here is that even someone as driven as Kusama (and let’s face it: Manhattan-bound Modernists of the era were all Warholian in their power plays and publicity drives) projects a mute voice that carries beyond these damming theatrics.

Visitor in front of Yayoi Kusama’s Untitled (No. White A.Z.), 1958-59, at Yayoi Kusama exhibition at NGV International, Melbourne until 21 April 2025. © YAYOI KUSAMA. Photo: Danielle Castano

The next major painting in Room 1 is Pacific Ocean (1958), painted the year Kusama migrated to New York City. Again, the painting’s seemingly traditional exercise in Minimalist Abstraction is invisibly bifurcated by an undercurrent which dynamises the work beyond its categorical appearance. A large, widescreen oil formed by meandering white lines atop a black undercoat creates a myriad of organically formed nodules, whose undulate spread suggests an oceanic realm. A didactic panel explicates the painting’s scale and scope through Kusama’s claim to be have been inspired by seeing the Pacific Ocean en route to America by plane. But this misses the ingrained sense of maritime energies that surround and support the “island nation” psychogeography of Japan, and, by extension, Kusama’s own view of her homeland. Standing in front of this marvellous canvas conveys a thrilling sense of how she figured natural forces as operating beyond human sense. Abstraction as a visual discourse has long been positioned to deny equally perspectival and ecological reference, but the multi-dimensional history of “landscape painting” in Japanese painting for two centuries muddies these binaries.

More importantly, for post-Occupation Japan, the Pacific Ocean signified something drastically specific: radiation exposure sustained by the crew of the Lucky Dragon No.5 tuna fishing boat following the detonation of the US “Castle Bravo” nuclear bomb test at Bikini Atoll in 1954. Across the next five years, Japan–US relations would reach breaking point as the Pacific cradle of Japan’s long Eastern coastline would become contaminated chemically and psychologically, while the US government officially denied responsibility. The Marukis addressed this national destabilisation in their ninth mural Yaizu (1954). On the surface, Kusama’s The Pacific Ocean would appear to sidestep the socially committed program of the Marukis. Yet, with its uncharacteristically blunt title, it draws attention to a consciousness that results from registering nature less as something to be represented and more as something that exists beyond human imaging. For some, the painting will exude the dull, mouldy patina of early Modernist abstract oils. Yet when one focusses on the brushwork, optical synaptic sparks can be perceived like eye floaters on one’s vitreous humour. Indeed, I feel persuaded to sense an ocean teaming with life, visible as shimmering clouds of fish whose underwater tornadoes result from the structural colorization manifest through light particles hitting the nanoscopic surface structuring of their scales. Their metallic glint is not a matter of pigmentation, but of dynamic light interaction. Similarly, The Pacific Ocean seems not to be essentially visual. It’s not a stretch to consider these phenomenal optics and their natural origins as laying the groundwork for Kusama’s retreat into psychic spaces, where such energies would be simultaneously trapped and unleashed.

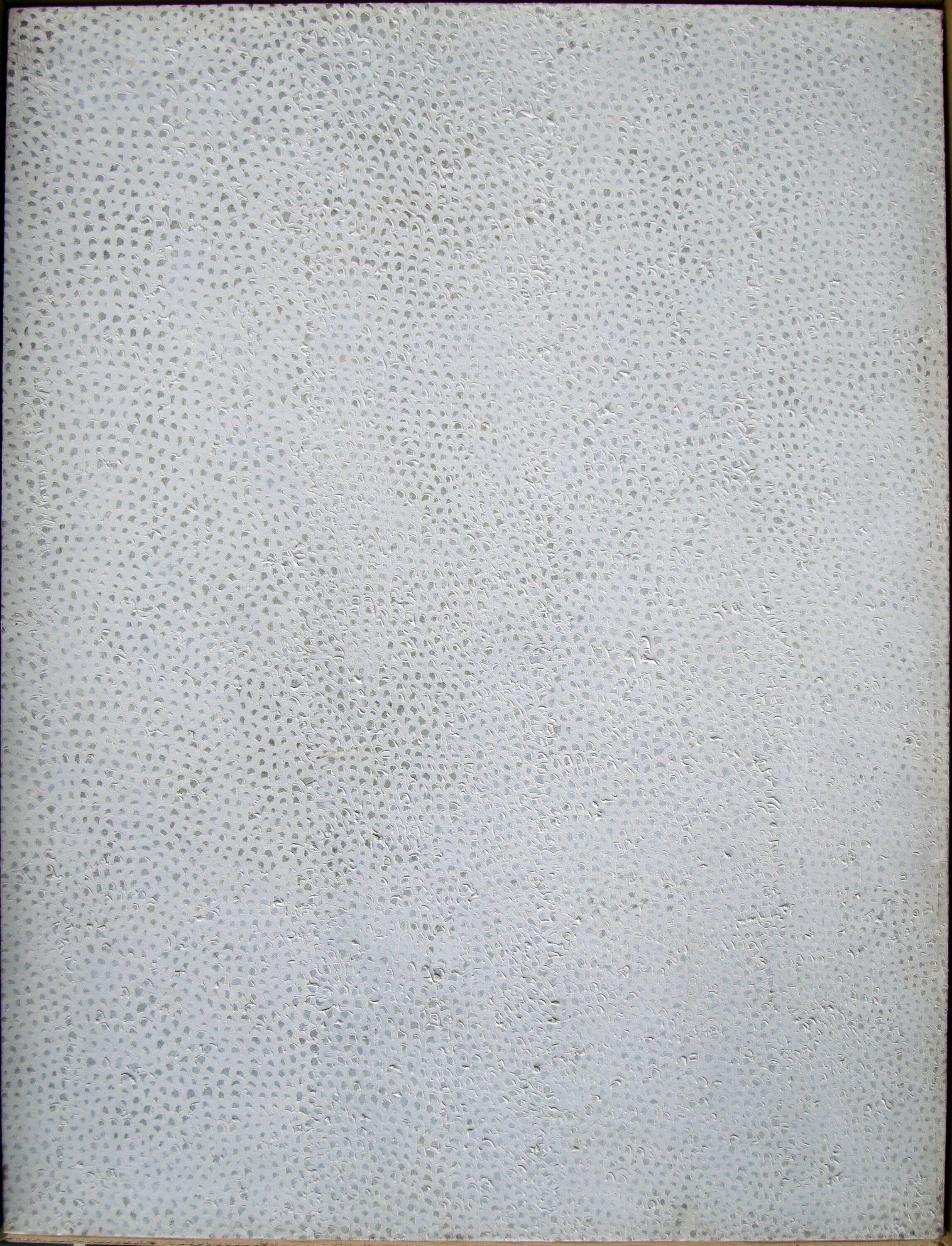

Two additional works in this mode—No.10 FB and Untitled (No. White A.Z.) (both 1959)—sprout further associations between visual mechanics and ocular sensation. No.10 FB is a variation on the canvas being transformed by waveforms, in this case created by dark shapes crazy-paved in throbbing clusters and eddies. Painted with sumi ink on mulberry kōzo paper, it conveys a tactile sense of manual repetition and continuity, reminding the viewer of sewing, threading and knitting. The brushwork is neither painterly nor calligraphic: it is simply evidence of a planar accretion that continues its process toward all four edges of the quadrilateral. Not wishing to play the gender card with a heavy hand here, but one wonders how the rebellious Kusama related to Japanese women’s quasi-carceral contribution to the sericulture industry and its accelerated post-war production (portrayed in Shohei Imamura’s terse 1963 film The Insect Woman). The mulberry tree’s inner bark generates the material for kōzo paper, while its leaves provide sustenance for silk moth larvae whose cocoons will generate silk thread to be spun in mills. While this resulted in aesthetic finery, the production and sewing of silk parachutes during Japan’s Pacific theatre of war for its heroic paratroopers was a major activity carried out by girls and young women—including a teenage Kusama at the time.

Untitled (No. White A.Z.) is among the first of Kusama’s oils to employ her looping brushwork that articulates a self-breeding pattern of crescent enclosures, soon to be labelled as “nets” (and their eventual morphing into the closed brush daubes of her “dots”). It plays with positive and negative space through the brushwork ambiguously being both schematic outline and formed shape: the looping lines are either circles or dots; arcs or discs; waves or globes. Well before Takashi Murakami’s thesis on “Superflat” visuality in Japanese mimesis, Kusama’s abstract oils were predicated on how the visual plane before one’s eyes was a flat surface that coated the world like a patterned filmic ectoplasm. Think of this film as a discursive veil hovering between you and the objects you identify—as well as those things that stubbornly remain inexplicable to the eye and mind. Kusama was painting neither still lifes nor interior states: she was visualising acts of seeing, rooted in real world sensations rather than imaginary embodiment.

Yayoi Kusama, Infinity nets (2), 1958, oil on canvas. Collection of the artist ©YAYOI KUSAMA

Viewed through the lens of Art History, Untitled (No. White A.Z.) (and its brethren in the Infinity Nets series commenced in 1958) can be linked to Robert Rauschenberg’s White Painting series (1950, exhibited in full for his powerful career survey held at MoMA, New York in 2016). This isn’t a slight connection: Kusama embedded herself in the experimental transmedial clique of post-object artists in New York’s late 1950s/early 1960s downtown milieu. Rauschenberg remains one of the key figures here due to his collaborations and connections with John Cage, David Tudor, Fluxus, Billy Klüver, E.A.T., Merce Cunningham, Trisha Brown, Jean Tinguely, Nikki de Saint Phalle, et al. In many senses, Rauschenberg’s combines were the “skin” of New York’s city streets with all their audiovisual, multi-dimensional, sensorial noise. Kusama would gradually adopt a similar perceptual procedure of “sensing the world” around her. But Untitled (No. White A.Z.) curiously resonates not with “the street” but with the sea. Cued by Kusama’s terminology, the painting can be seen as a dense palimpsest of fishing nets, bereft of any catch, floating in a void, poetically conjuring a “skin” of the ocean that infers a uniquely Japanese perspective on aquaculture. The eternal cycle of threading, sewing and repairing nets is central to the act of fishing, placing it remarkably near to the repetitive focussed task of brushwork which progressively consumed Kusama.

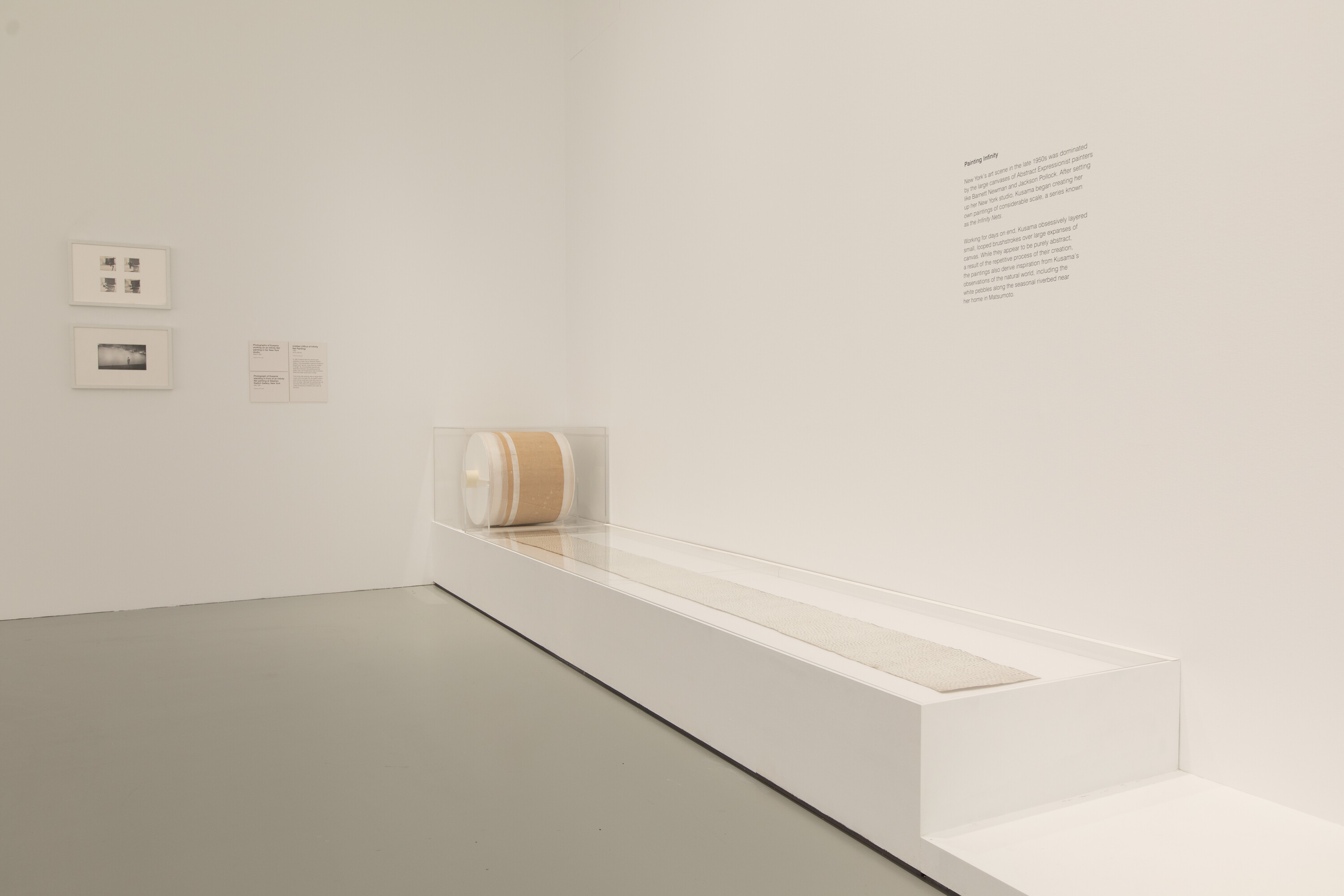

Installation view of the Yayoi Kusama exhibition at NGV International, Melbourne until 21 April 2025. © YAYOI KUSAMA. Photo: Kate Shanasy

An additional connection with Rauschenberg is evident in the exhibition’s display of Untitled (Offcut of Infinity Net Painting) (1960), here presented as an offcut strip of white painted canvas rolled onto a cylindrical drum. Though claimed as resulting from the original mural-sized canvas being too large to fit through Kusama’s studio doors, its presentation here overtly references Japanese emakimono handscrolls, whose narrational pictorial texts attained artistic status during the Heian period. Through Cage in particular, the downtown experimentalists found much inspiration in Japan’s non-Western/counter-Euclidian/post-human notions of time, space and being (and, consequently, of how to image the world). Rauschenberg and Cage’s Automobile Tyre Print (1953) playfully riffs on these ideas, creating by rolling a car tyre smeared with black house paint on 20 sheets of typewriter papers glued together and mounted on an 8.5 metre fabric strip. Automobile Tyre Print implies mobility, action, and a displacement of fixed perspective. Again, these would become major traits in Kusama’s Infinity Rooms, which treat the viewer as a molecule within a fractalized environment of replicating and interlinked surfaces.

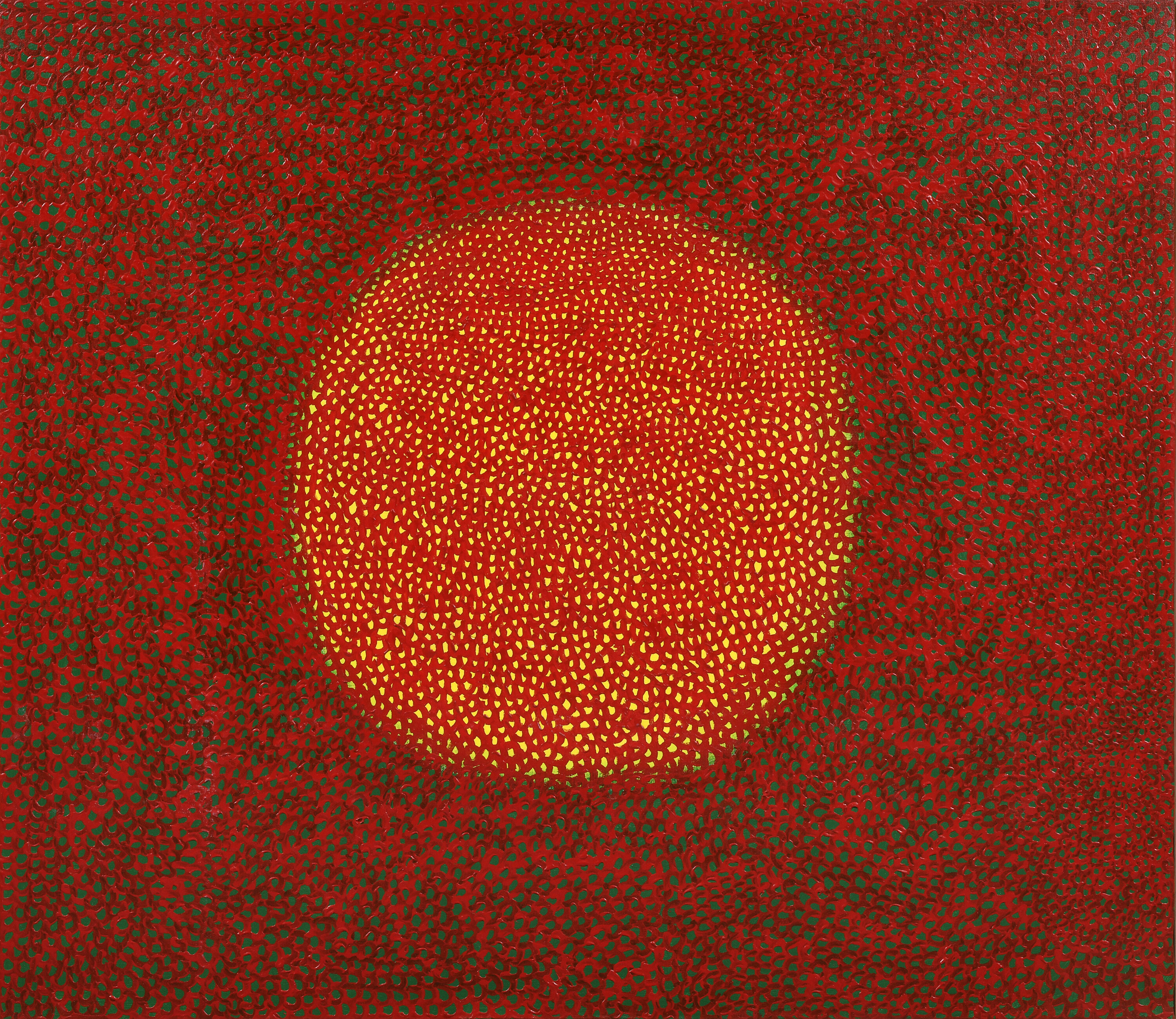

A final painting of note in Room 1 is Infinity Net (1965). By this stage, Kusama’s application of painterly netting had become controlled, consistent, and continual. This variation in the series fashions the hinomaru red sun ball of the Japanese national flag into a fiery orb of cadmium red and yellow, boiling in a lacunal expanse of stroked crimson on bottle green. Kusama’s steady hand has rerouted the traditional calligraphic statement of identity through mark-making into an atomized patterning of brushiness devoid of personal statement. It’s a coup de grâce, actually: to state in paint “I am nothing but paint; I am nothing but painted; I am nothing but painting.” This Infinity Net, however, is not a unique marker, and is better understood by Kusama’s severed brethren back in Japan, who grappled with identical dilemmas. The most obvious connection would be with Jiro Yoshihara’s commitment to single-stroked circles in the Circle series he produced in various media since 1962. Hisao Domoto’s Solution of Continuity series also since 1962 follow a more expanded trajectory, choosing giant hinomaru dots, which made his paintings resemble Rauschenbergian collage canvas by evoking Japan’s nationalistic flag-plastered advertising in the lead-up to the 1964 Summer Olympics in Tokyo. These artists and more constitute a diasporic spread of critical Pop artists using the Japanese flag (be it sardonically, intuitively, or unconsciously) in ways similar to Rauschenberg, Jasper Johns, Larry Rivers and James Rosenquist’s use of the US flag. All voiced a sense of razed nothingness and phantom nationalism in the face of the era’s new machinations of societal control through media imaging.

Yayoi Kusama, Infinity Net, 1965, oil on canvas, 132.0 × 152.0 cm. Collection of Daisuke Miyatsu. © YAYOI KUSAMA

This brings us to Kusama’s declaration of “Self-Obliteration.” It’s a concept too dense (and vague and broad) to unpack here, due to its merging of Foucaultian self-therapy and Zen self-awareness. Kusama articulated it initially through performative actions, which extended her obsessive brushwork into a Kaprow-styled notion of expanded art making. Essentially, she would literally paint dots anywhere and everywhere so as to render the world a screenic continuum of the hallucinatory affliction she bore wherein she saw dots before her eyes. Museum surveys of any of the radical and experimental artists noted above invariably cite the US counterculture of the 1960s as being an important incubator for artists aligning themselves with seismic changes in society. (The NGV’s Room 1 subscribes to this origin story model.) In such instances, quaint amateur photographs present public actions that historians and curators alike find charming and influential. I am nauseated by archival photos of hippies, yippies, and assorted “heads” going out to administer truth trips on the straights.

The Kusama exhibition’s concluding work in Room 1 is a telecine of her collaborative 16 mm film Kusama’s Self-Obliteration (1967). The scenario & art direction is by Kusama; the twenty-four minute movie is filmed and edited by Jud Yalkut (an experimental filmmaker for the USCO “Company of Us” media arts collective, and technical collaborator with Nam June Paik at this time). Dressed in a red cape dress festooned with large white fabric dots, with smaller dots in her black flowing hair, Kusama wanders through Central Park like a witchy Alice, transforming nature and the world through her application of dots. She sticks them on a dark horse and rides it like a vogued Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood femme (the type who frequently adorned Filmore East rock posters at the time). She paints dots on lily pads in an idyllic pond, and even wistfully attempts to put dots on the water itself, the paint dissolving amidst concentric ripples. If I were kind, I would accept this as a time capsule of youthful abandon and unrestrained revelry in the name of avant-gardism—the type that thrives as Bad Performance Art today. In place of sync, the sound is woeful, generic, Acid-toned doodling by The C.I.A. Change (The Centre for Interplanetary Activity). This roomy, sub-blues, pseudo-Moroccan, Doors/Dead-styled exotica is combined with what the film credits as “liquid sounds” by Aurora Glory Alice. I’m surprised it hasn’t yet been released on vinyl for Record Store Day.

Yayoi Kusama, Self-Obliteration, 19671. 6mm colour film with sound transferred to digital video, 23 min33 sec. Cinematographer: Jud Yalkut. Collection of the artist© YAYOI KUSAMA

Yayoi Kusama, Self-Obliteration, 19671. 6mm colour film with sound transferred to digital video, 23 min33 sec. Cinematographer: Jud Yalkut. Collection of the artist © YAYOI KUSAMA

Standing to watch this bleached lo-res telecine of Kusama’s Self-Obliteration was an endurance test. The projection was incorrectly aligned so that the image was cropped by about twenty percent along the left and bottom edges, plus the image bled its right edge ten percent onto the surrounding black wall. Yet despite its shoddy production and presentation, its celebration of a delusional vitality, and its forensic evidence of vapid hipsterism, it clarifies Kusama’s world view (literally, figuratively, and optically) at this juncture of her career. The film contains a few flash frames where still images of the U.N. Building, the Statue of Liberty and 40 Wall Street are overprinted with large white dots. With Taro-like glee, it is as if Kusama is “dot-bombing” the phallic architecture of Manhattan’s power centres. The obliteration might be tagged with the Self, but, like all Modernist art of the era, it trades in painterly plosions of artistic voices that wield brushes like guns. This is less to do with Kusama per se, and more to do with how image culture—amidst the sloppy countercultural gestures towards mainstream societal critique—was complexly overpowering everyone, especially artists who imagined themselves beyond these effects. Kusama’s notion of “self-obliteration” from this point travels down two roads: one burrows into the dark reality of her schizophrenic condition; the other taxies her identity in an expanding global “dot-bombing” of the world inside and outside the art museum. Kusama exists nowhere and everywhere at the same time.

Philip Brophy writes on art among other things.