Working Models; Light Weight / Light Well

Jeremy George and Camille Orel

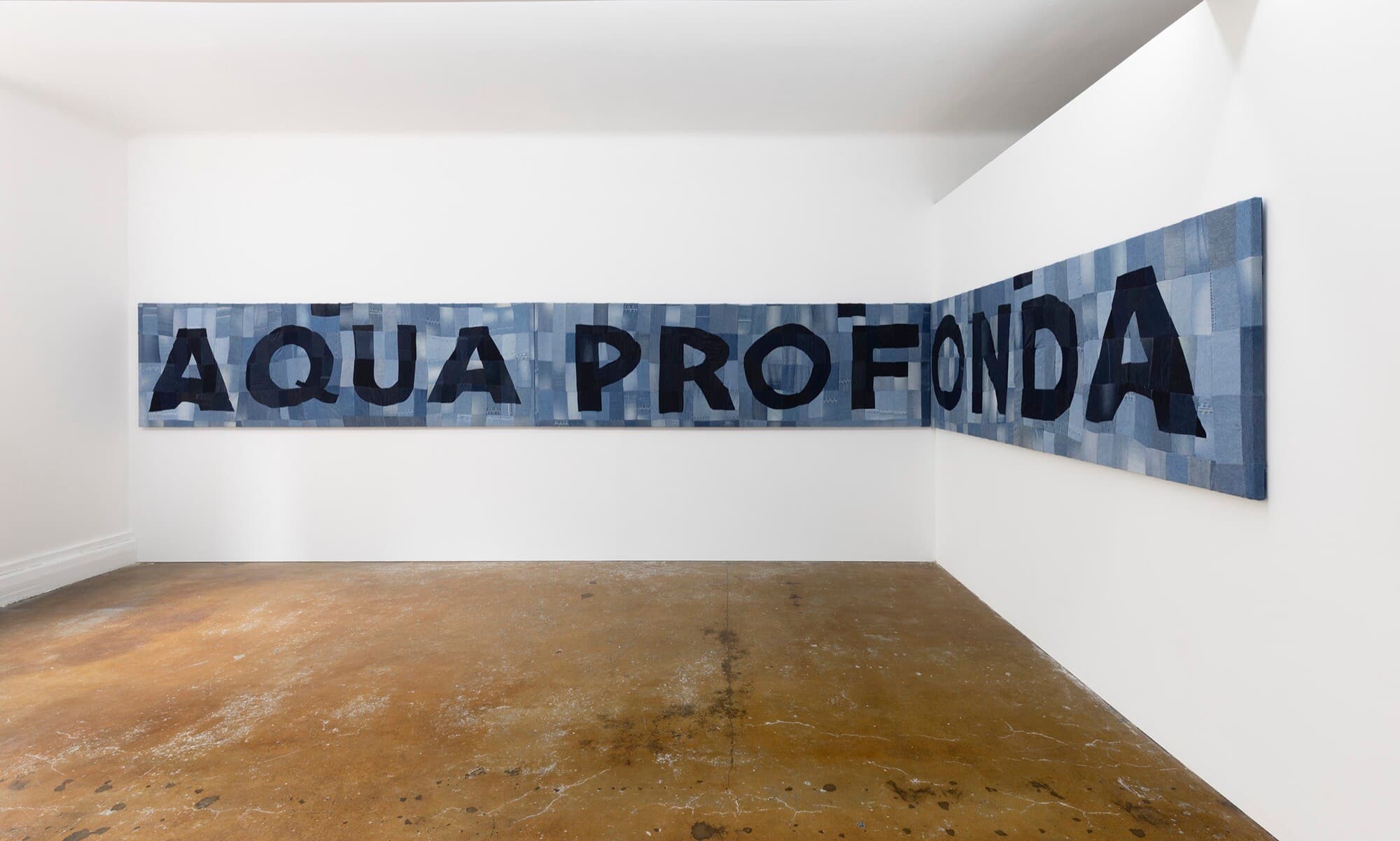

Rose Nolan has been doing things with words since the 1980s. Her expansive practice has included the production of books, small sculptures, photographs, posters, paintings, banners, multiples, and large-scale installations. One throughline across all these mediums has been a preoccupation with the fraught dynamics between language, lettering, and formalism in artmaking. Her work has inventively borrowed, and in the process sloganised, snippets (usually single words or phrases) from books, catalogues, advertising, and everyday conversation. In the spirit of Nolan’s commitment to the ethos of the twentieth-century avant-garde—with all the ferocious ambition and utopian possibility that was invested in artmaking—we might call this spatial poetics.

Currently open in Melbourne’s CBD are Nolan’s two solo exhibitions: Working Models at Anna Schwartz Gallery, and Light Weight / Light Well at the small artist-run outfit Hyacinth. It’s not often that an artist gets the opportunity to sync two solo shows just down the road from each other on Flinders Lane. It is an especially generative double-barrel for the different opportunities afforded by each gallery: the former an established and large space which also represents Nolan commercially, the latter a more provisional, “rip-it-up-and-start-again” project that often shows the art of a younger generation. Between the two some organising themes of Nolan’s extended practice are clarified, illuminating continuities that can be overlooked at a single exhibition. Working Models and Light Weight / Light Well are a minor retrospective in two fragments.

Upon entering Anna Schwartz Gallery, we experienced a moment of surprise. There is no sign of the large-scale, site-specific lettering work characteristic of her “Big Words” series. Information as Ornament (2016) was a reworking of Adolf Loos’s modernist treatise against design, blocked out in a ribbon of thermally folded, laser-cut Perspex curved in on itself to create a translucent life-sized pen. Disjuncture (2019) was a pedagogical imperative painted floor-to-ceiling on the wall of the Sydney College of Arts. Transcend The Poverty of Partial Vision (2021) dyed a Rosalind Krauss phrase from her book Passages of Modern Sculpture into the wool of a series of circular rugs covering the Schwartz gallery floor. All these works transformed language into interactive ideograms: the phrases became concepts you could walk around in.

Although Nolan’s scale has changed in Working Models, her commitment to formalism as an Ansatzpunkt— a point of departure from which to uncover the deeper and more profound layers of meaning and significance— remains. The Working Models appear compositionally balanced, precise, self-evident. Lined up along the steel framed display case Nolan’s models look like utopian meteorites, crash landed into the commercial gallery as the relics and memorial artefacts of a lost age. Upon closer inspection, Le Corbusier’s “five points of architecture” can be traced across the repeated pilotis supports used in NGV Contemporary (2019), Renzo Piano Store (2019), and Wrapped Temple (2022). The circular shapes used to describe Centrepoint Carpark (2023) recalls the curvature of Frank Lloyd Wright’s famous Guggenheim Museum stacked atop itself six times over. The geometry and colour palette of House of the Year (2023) simulates a three-dimensional cousin of Mondrian’s De Stijl compositions. The elongated double-tiered display shelf that houses Nolan’s thirty models, cutting lengthwise across the gallery floor, might even bear a resemblance to the diagonal axis of Monet’s canonical Poplars series, whose Impressionism predates the formalist abstraction of the twentieth century but remains an important modern reference nonetheless.

As we approach the individual models, it becomes obvious that the materials have all been found, mostly remnants of the packaging and wrapping that adorn purchased commodities. Canberra-based critic Chris McAuliffe once playfully described Nolan’s work as “scrap heap Suprematism.” There’s boxes of Twining’s tea bags; a Marimekko kettle; Issey Miyake perfume; countless balsa wood canisters of Will Studd’s Chèvre de la Forêt cheese. A cardboard relief that would have once held an Alvar Aalto Savoy Vase has been used for the model AA Hydrotherapy Pool (2022), whose title reconfigures the renowned modernist glassware design into a never-to-be-constructed backyard blueprint.

The materials used by Nolan to construct these working models not only transcend their original use as packaging, protection, and advertisement. They also represent the consumption and detritus in Nolan’s own lived-in world. We can imagine the artist’s peppermint tea steeping in her Marimekko teapot while she popped on a load of washing with her Fab laundry detergent. The inclusion of Stephen Bram’s lacerated abstractions in the exhibition flyer wrapped onto the model Home-Sweet-Home House Museum (2023) might be a reference to the 1990s live-in Prahran gallery Store 5. Originally initiated by Kerrie Poliness and Gary Wilson, Store 5’s programming—heavily focused on DIY installations, the use of unconventional materials (including, yes, trash), and one day exhibitions in quick succession—was an early expression of the speed-freak punk ethos now considered characteristic of Melbourne’s more recent art scene. Both Nolan and Bram had work in the gallery’s first exhibition in 1989.

Nolan’s quiet utterances of subjectivity and nostalgic echoes are not self-indulgent. On the contrary, by embedding these hints of individual experience and consumption into the materiality of the working models, Nolan has re-coded them into a kind of visual language. Nolan’s geometric nod to a lineage of the twentieth century avant-garde also recalls Russian Constructivism, both aesthetically and in its utopian ambitions. It is interesting to recall that, before the epic axe of Socialist Realism cut down the sapling movement, Constructivists were committed to the idea that their abstractions could serve as models for testing alternative, more fully human ways of life: they were to be grounding forms in which to shelter and recover from the spiritual inanition and anomic drift of capitalism. Nolan’s decision to fashion her Constructivist models out of the memory-waste of everyday living—embedding them within a new imagination in the process—seems like a moment of culmination in the twenty-first century for this avant-garde project.

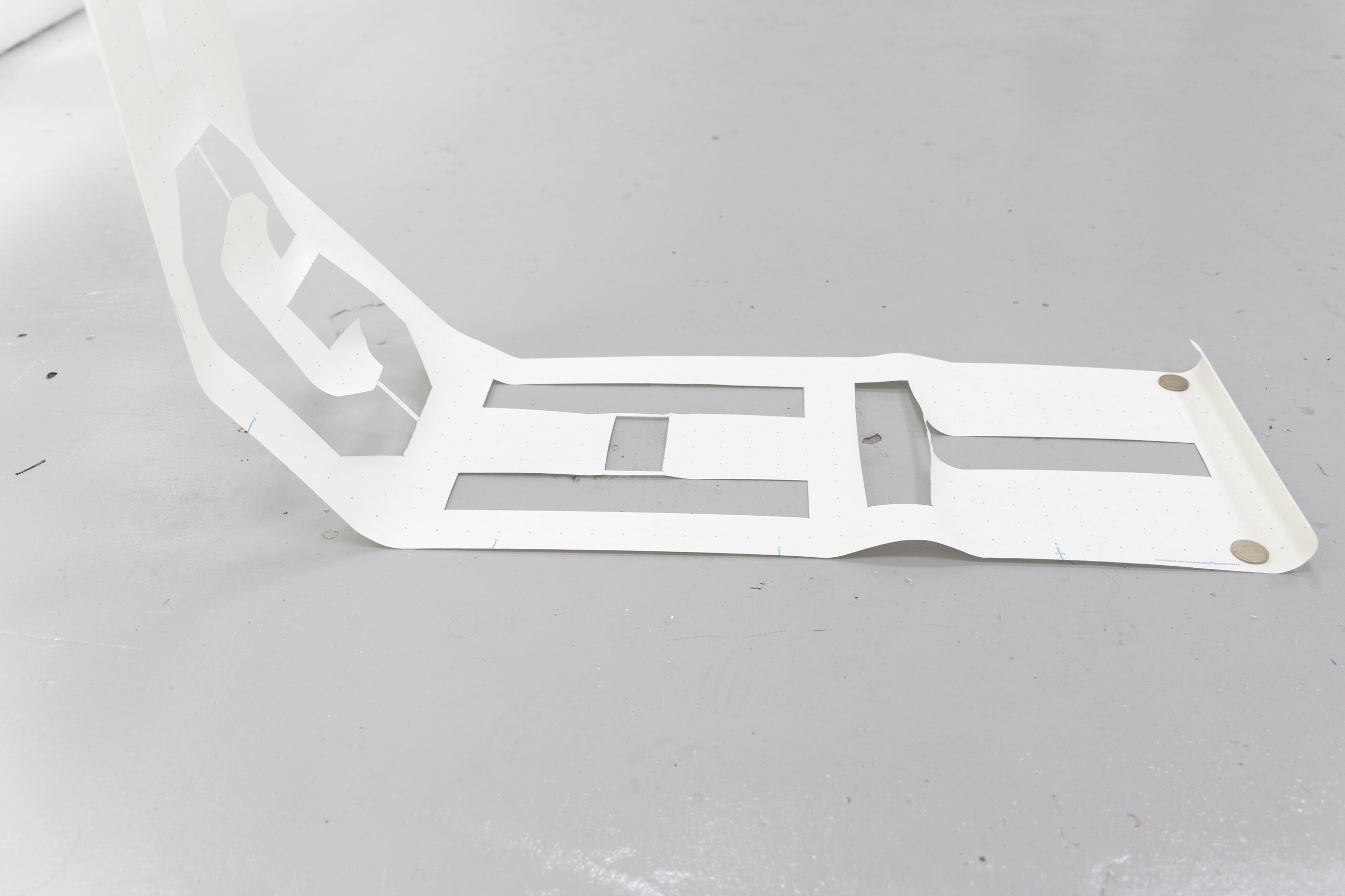

Light Weight/Light Well restages a banner-work Nolan first produced for the group show Performance Anxiety at Julie Davies and Alex Rizkala’s gallery Ocular Lab in 2004. Hyacinth has suspended the white monochrome tracing paper from the centre of the ceiling. It dips gracefully to the gallery floor, which is fastened with a minimal support (two twenty-cent coins), thus relying on the work’s internal weight to generate the convex, scroll-like unfolding hang. Vertically down the banner LIGHTWEIGHT is stencil-cut out of the tracing paper. The semi-transparent stencil resembles a skeleton frame for one of the red-and-white text-based works that Nolan is better known for. Like her Working Models, an originally transitional object has been taken-out-of-time and promoted to the status of artwork.

It is from the lettering carved out of the paper that we can understand the exhibition title Light Well in both its imperative and descriptive cases. To make out the slogan, the work must be lit well! We first saw the show after arriving late to the exhibition opening. It was around 8 pm, dark outside, crowded inside. We didn’t appreciate the true loveliness of the work in the space until returning one afternoon a few days later. The artificial gallery lights were switched off, the space relied on the daylight seeping through the two floor-to-ceiling windows that look into the light-well that hollows out the centre of the Nicholas Building. The indirect sunlight kept the room awash in a soft, greyish glow that gently brightened and dimmed as the invisible sun moved across the sky.

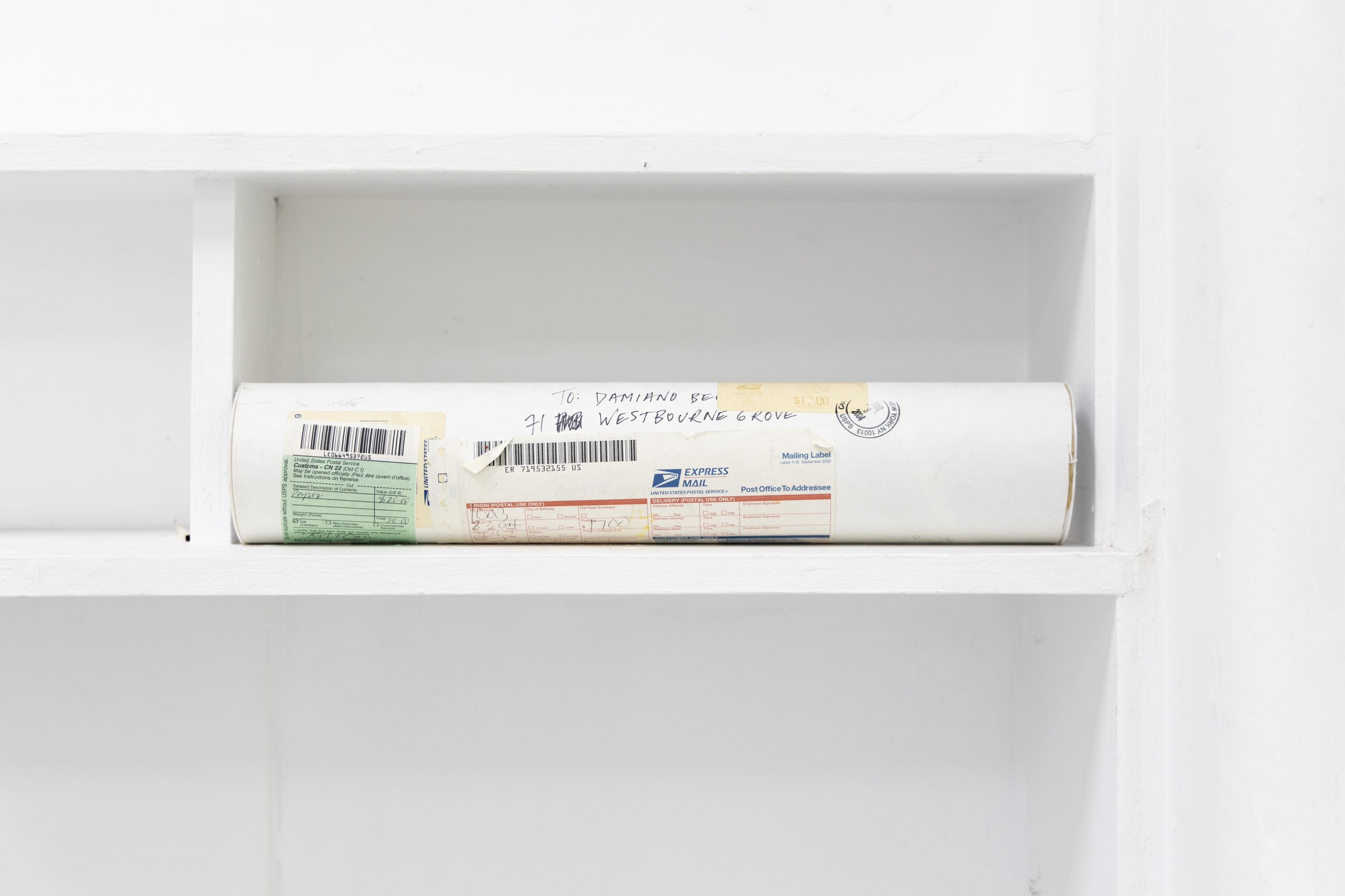

The paper banner runs parallel to the narrow wall dividing the two large gallery windows. By tracing the seams of the room, Nolan has also transformed Hyacinth into a version of the light-shaft onto which it gazes. At the right time of day, the gallery blanches into light and we move into the air. Disoriented, we are drawn towards the other component of the exhibition stashed in the corner of the gallery, the original packaging tube Nolan sent from New York to Damiano Bertoli in Melbourne. This tube is another utopian artefact of times past, a meteorite of recycled material torpedoed into the present. Like the working models and the stencil-banner, this provisional supplement collapses the history of art with the art of history, splitting open the present and holding it out to stormy possibility with the iron clamps of abstracted language and geometric form.

Camille Orel is a writer. Jeremy George is a PhD candidate at the University of Melbourne.

This review was made possible thanks to the generous support of MERIDIAN SCULPTURE.