We get in touch with things at the point they break down // Even in the absence of spectators and audiences, dust circulates

Tara Heffernan

In his critique of the intellectual left’s body politics, disability scholar Lennard J. Davis argues that “the disabled body is a nightmare for the fashionable discourse of theory”. The same could be said of the fashionable discourse of contemporary art. Rather than face the disabled body as a reality, trendy culture makers turn “to the fluids of sexuality, the gloss of lubrication, the glossary of the body as text”. As somebody who was born legally blind, I have often thought about the way disability manifests in literature and art, and its amorphous metaphorical interpretations. This concern was reignited by an exhibition currently housed at West Space. We get in touch with things at the point they break down // Even in the absence of spectators and audiences, dust circulates … brings together several collaborative projects and artworks by Australian and international artists and writers. Culminating in a multi-sensory gallery experience which privileges haptic encounters, curator Fayen d’Evie uses blindness as a vehicle to subvert ocular-centric musicological practices, a concern that stems from her own diagnosis with a degenerative vision impairment.

Upon entering, the gallery space immediately struck me as rather empty. Most of the works are quite subtle and small or else confined to the walls. Perhaps intentional, this curatorial move made it easier to navigate, removing the threat of expensive obstacles and awkward explanations. However, subtle multi-sensory revelations emerge as you traverse the gallery. Transparent parabolic dome speakers suspended from the ceiling don’t encroach on the space. The localised audio experience (accompanying video works) might surprise you if you walk beneath them unknowingly.

Essays in gestural poetics (2021), created by d’Evie, Anna Seymour, Vincent Chan and Trent Walter is a series of tactile A4 acrylic panels. The monochromatic sheets display flora samples. The leaves of Victorian Ash trees, with their elongated natural forms, are differentiated through varied textures, providing an impression of their shape and contours that can be mapped through touch. Whether able-bodied people realise or not, tactile surfaces are part of our everyday environment, and many rely on them to maintain a degree of bodily autonomy. A common feature of Australian streets is the PB/5, an innovation in Audio-Tactile Pedestrian Detectors developed in the 1980s in New South Wales. It features a braille direction arrow and pulsates with a two-rhythm buzzer to help hearing and vision-impaired pedestrians cross the street safely (unless they are malfunctioning, which they often are). Known as tactile paving, the geometric columns of raised bumps or bars that feature on footpaths, stairs and train stations help the vision-impaired navigate busy public spaces.

Continuing the exploration of tactile reading, one of the most prominent pieces in the show is a vitrine created by Melbourne-based artist and writer Lizzie Boon. The vitrine houses a draft publication layout of Sofia Lo Bianco and d’Evie’s Care is a Cognate to Grief (2020/2022), a product of 3-ply (an independent publishing initiative founded by d’Evie). Through a protective layer of perspex floating atop the vitrine, the paper beneath drapes over the edges of the display surface exposed to the elements. Although the paper is heavy, it seems occasionally to billow, pushed by air circulating around the room. Embossed text across its surface can barely be seen under the light of the gallery space, aside from a hint of a shadow perceptible to those with particularly good vision. Tactile encounters are encouraged, as the text explains:

to read is to erase,

erasure as an act of inscription,

that wears away at fragile dots,

while depositing oils and skin cells

This excerpt references an essay by Erica Fretwell, where reading by touch is described “as a form of autobiographical annotation”.

While there’s no shortage of artists and curators concerned with exposing the conventions and power structures within cultural institutions, d’Evie’s project is probably most aligned with the critical meteorological works of Hans Haacke. In a similar ethos to the one behind We get in touch …. Haacke rejected the term sculpture, preferring to refer to his projects as “systems”. The most subtle manifestations are his earlier weather works such as Condensation Cube (1965) which consisted of a plexiglass box containing a small quantity of water. Perpetually in a process of evaporation and condensation, Condensation Cube responded to the environmental conditions to which it was exposed: sunlight, the circulation of air and the humidity produced by the bodies present within the gallery. It was a process that inadvertently made collaborators out of spectators. Reflecting on the weather works, Haacke described them as “a site-specific ironic comment (on) the rarefied super-controlled environment in which artworks are exhibited in museums … their commodity/insurance values, and white glove treatment”. Though the vitrine is usually designed to protect art objects from the hands of gallery attendees and the dust and debris of public space, Boon’s design welcomes them. The paper becomes an index to register these encounters.

Creating a dialogue with the musicological bent of tactile prints and the vitrine, Museum Incognita: Bundles (2021) comprises a series of small sculptural works resembling artefacts for museum display. Museum Incognita is a project curated jointly by d’Evie and artist Katie West with the aim of activating “collective readings of neglected and obscured histories” as explained in the exhibition text. Included in this iteration are Spine (—) and … on and on and on … (tactile poetics fragment) (2019), two heavy, oblong objects. The former is a cold, sanded block of Jurassic marble while the latter is a slender bronze bar bearing its title printed in braille. The sculptures are tightly wrapped in embroidered fabric dyed with bark, leaves, flowers and mud from Jaara country, where d’Evie resides. Their tight packaging suggests a process of careful preservation, although the embroidered material—itself a delicately crafted artwork—evokes a familial warmth opposed to the sterility of archival preservation processes.

The final bundle in Museum Incognita contains Sophie Takách’s handling (encounter between Fayen d’Evie and Georgina Kleege) (2016–2021). The bronze cast captures the negative space between clasped hands, in this case, those of d’Evie and Georgina Kleege, a legally blind Berkeley professor who has published several books on blindness and art. Kleege has also championed art education and accessibility programming in which she emphasises the significance of other sensory encounters with objects: their weight, texture, temperature and density. All these qualities are not necessarily apparent through purely visual encounters. Accordingly, visitors to West Space are encouraged to unwrap the bundles and explore them via touch. In contrast to the geometric negative spaces of Rachel Whiteread, the Takách sculptures resemble strange organic shapes, like fungal forms or sea-creatures. It might take time to discern their origin and to locate the specific contours of the body they record. In the case of handling, realisation might be activated by replicating the gesture, or a vague approximation, with fumbling hands.

Though there are resonances within the recent history of art, such as Haacke’s weather works, these projects also possess parallels with broader cultural trends. Since the early 2000s, there’s been a growing interest in non-visual sensory experience in marketing and product design. Canadian cultural theorist David Howes explains the new emphasis on the “sense appeal of commodities” as capitalism’s successful colonisation of bodily experience in an era driven by immediate gratification. Haptic capitalism places great importance on the texture, weight and shape of products and their packaging, while there’s a rising market in bourgeois self-care items catering to non-visual sensory delights. Think of the new obsession with handcrafted ceramics, weighted blankets, and the proliferation of scented products such as artisanal tea, bath products, sprays (face, linen, room, bed or car), candles, incense, oil burners and diffusers. Though it might be inadvertent, this parallel demonstrates a pervasive cultural appetite for multi-sensory engagement.

Quoted in Art Guide Australia, d’Evie explained her project as reclaiming “the agency of blindness”, while lamenting the pejorative phrases associated with disability (moral blindness, blind drunk, lame, etc). D’Evie notes that these turns of phrase have received comparatively less critical attention than other examples of problematic speech. To understand why, I think we need to acknowledge why disability exists as a unique identity category. Unlike issues of race, gender or sexual preference (which disadvantage the individual due to external factors: racism, sexism, homophobia, cultural insensitivity, lack of access to resources due to geographical or economic constraints), disability identifies a problem that is inherent to the body. In other words, the limits and struggles of disabled people are not exclusively externally imposed, but can be largely attributed to the body’s own atypical character. This is likely why recurrent campaigns to rebrand disability as “differently abled” or otherwise remove negative associations receive so much pushback. For example, in a guide produced for last year’s Melbourne Fringe Festival, activist Carly Findlay noted that terms like “diffability”—meaning differently abled—only create more stigma. These attempts to repackage disability as merely a different experience or way of being ignore the real and tangible struggles faced by disabled people living in a world that is not built with their bodies in mind. Moreover, disavowing the original term inadvertently serves to underline negative associations. To treat disability as a bad word is merely to acknowledge that it has barbs.

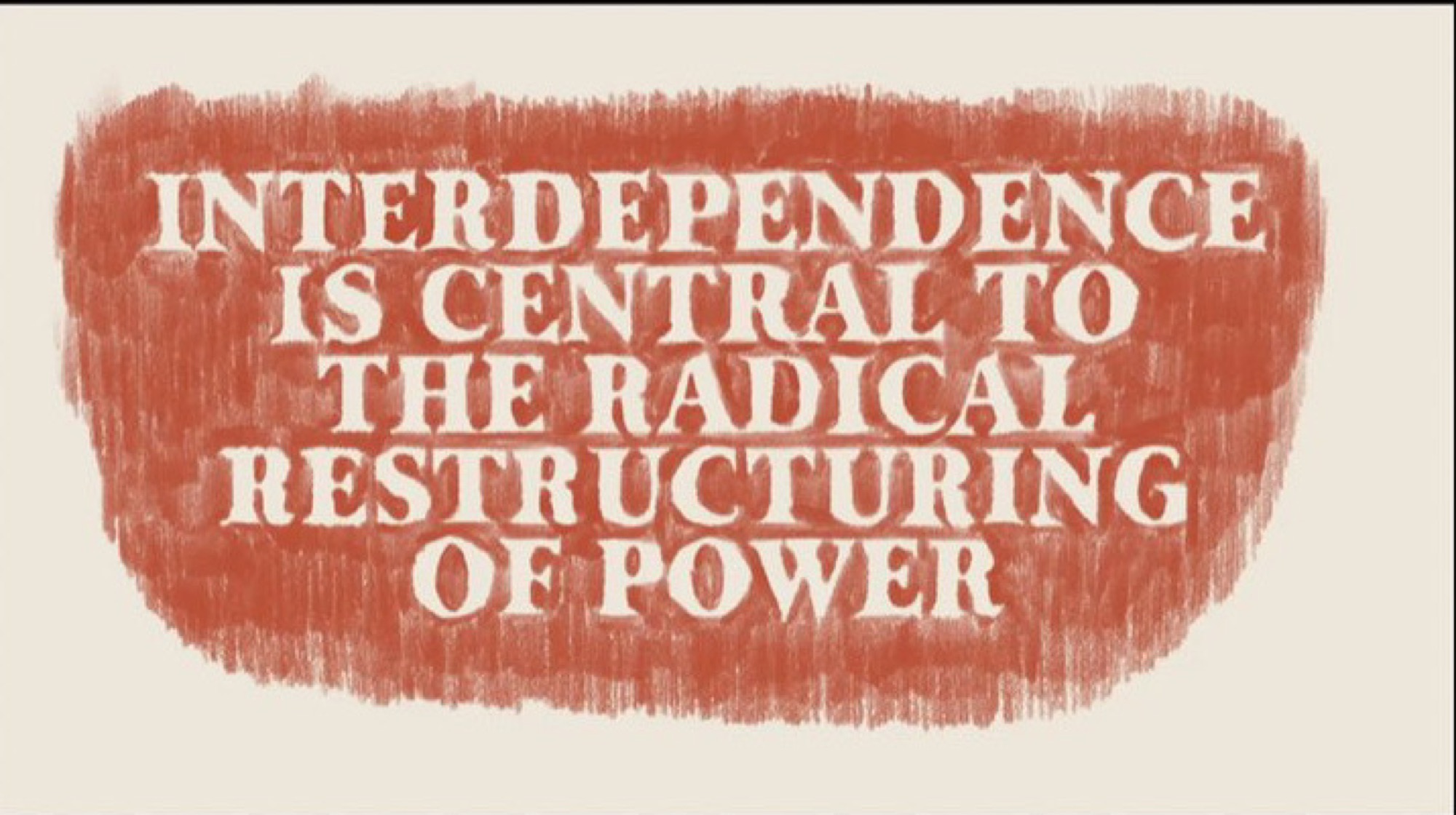

This criticism is mirrored in academic discourse. In his response to postmodern body politics (quoted at the beginning of this review), Davis cautions that the playful metaphorical appropriation of disability risks obfuscating its lived reality and its intersections and inconsistencies with other forms of oppression. While We get in touch … might participate in a comparable act of obfuscation by employing blindness as a vehicle to explore other sensory encounters, ways of making and thinking, the inclusion of Carmen Papalia’s presentation Open Access: Accessibility as Temporary, Collectively-Held Space (2020) provides a necessary counter. In this presentation, Papalia conveys his experience as a blind person in the navigation of his art practice and everyday life. After exploring disability through a series of collaborative performances (including one where he “disables” a friend by strapping a large sign to his back), Papalia penned his Open Access Statement. Read in full during the video, this statement proposes a radical reimagining of the process of accessibility. Unlike a traditional policy that “temporarily removes a barrier to participation”, open access responds to “those present, what their needs are”, providing a “support network that adapts as needs and available resources change”.

As much as Papalia’s proposal sounds like a pragmatic reshaping of the dialogue around disability and access, I can’t help but feel it doesn’t account for those acting in bad faith. It doesn’t acknowledge how such agreements can be (and often are) reshaped and manipulated when they enter non-ideal environments. In Vladimir Nabokov’s Laughter in the Dark (1932), a project that paved the way for his controversial classic Lolita (1952), blindness serves as a heavy-handed metaphor for naivety. Long before Albinus loses his vision in a car accident, the trusting protagonist fails to recognise the deception occurring before his eyes: an affair between his teenage mistress and bohemian houseguest. When he loses his sight, his antagonists delight in increasingly cruel, taunting behaviours. One favourite game involves disorientating Albinus with continually changing, fabricated descriptions of his surroundings, such as the colour and placement of furniture and décor, the presence of people or animals and the time of day. In the past decade, increasing attention has been placed on providing descriptions of visual information for the vision impaired. Such a task obviously involves a lot of responsibility and could easily be weaponsied. While image descriptions seem rather straightforward for non-Nabokov characters (there are plenty of guides available online), a more challenging task emerges when people are asked to describe themselves or others. Many Australian art galleries have recently begun encouraging this at the beginning of public lectures or panels. After the chair and each member of the panel provide their own acknowledgement of, or welcome to, Country, they offer their pronouns and a description of themselves, often including their race, age, and the style and colour of their clothing and hair. Inevitably, these are sometimes confused or clumsy descriptions, likely owing to the panellist’s lack of familiarity with the process, but also to the dissonance between visual cues associated with gender or race and their lived reality. For example, you might be an Indigenous person and have blond hair and blue eyes. A description of skin colour could mean many things.

It’s difficult to ignore that these descriptions are a laborious process. Inevitably, they occupy a lot of space in panels that are often scheduled for no more than one and a half hours. Moreover, it’s worth acknowledging that the task of describing yourself is also about your own political project of self-identification—something that matters to sighted people as much as it does to the vision impaired. I would argue that this process inadvertently constitutes an admittance that—in liberal cultural settings—the content and value of our ideas, positions and arguments must be read through, and qualified by, our identity markers. If you find this suggestion dubious, then I ask you to consider what isn’t said. What is omitted from these descriptions? If you’re disfigured, do you mention that? What if you have a prominent scar or birthmark, or if you’re particularly sexually attractive (or not)? What if you’re wearing expensive designer clothing? These are equally if not more important factors in representing yourself and characterising your experience. But these things are often ignored out of respect (and perhaps because they are not attributes that can easily be leveraged into a desirable narrative about oneself, or admirable status within a community). The slippages between visual data, meaning and value—revealed through this apparently descriptive process—can tell us a lot. This is not to suggest that image descriptions are a bad thing. Obviously, they are incredibly useful and the growing interest in facilitating accessible and inclusive material is undoubtedly helpful to the vision-impaired community. However, there’s reason to acknowledge their limitations and context. Image descriptions obviously cannot be objective. They are born out of and represent changing liberal value systems that inevitably privilege the visual.

Papalia’s Open Access Statement inspired the establishment of a residency called Bureau of Radical Accessibility at The Model, Sligo in Ireland. Papalia was one of the first artists to attend the program. During his time there, he tied a red cord to fixtures in the gallery such as hand railings and table legs to help him navigate the particularly confusing space. This “tactile wayfinding device” provided a “temporary system of access”. Carmen explains, “this really improved my experience there and it also disrupted commonly used routes for other people, so they had to negotiate this red cord as well”. This line really resonated with me. To my mind, it strikes at the core of what it is to be disabled and what might be radical about it. For people to make allowances for your disability, they might inconvenience themselves, sometimes a little, sometimes a lot. There will always be vulnerable members of society who might struggle to repay the kind gestures and favours of others. In an atomised culture—where relationships are increasingly transactional, emotional labour is tallied, familial ties are increasingly distanced and the emphasis on sensitivity training and microaggressions has created a new job market in an increasingly precarious and competitive workforce—to be disabled is often to need more help, a series of gestures that might not be easily, or ever, repaid. It’s a kind of vulnerability that can’t hold up to the rise of toxic individualism.

We get in touch … commenced on the 9 July and was only open for four days before Melbourne entered its fifth COVID-19 lockdown. While there is a wealth of material available on West Space Offsite, including poetic responses to the exhibited works and Papalia’s full video presentation, it’s a particularly disappointing situation for an exhibition that so thoroughly engages non-visual sensation, breaking the “do not touch” taboo. For now, dust circulates.

Tara Heffernan is a PhD candidate (Art History) at the University of Melbourne. Her thesis concerns the work of post-war Italian artist Piero Manzoni.