Visions of Paradise: Indian Court Paintings

Francis Plagne

Visions of Paradise is an unexpected delight. Bringing together nearly 200 works on paper from the NGV's 1980 Felton Bequest acquisitions of Indian painting, the exhibition offers up a feast of fine details, lavish lifestyles and sizzling colours. Even for the historically uninformed viewer like me, the offerings are an irresistible invitation to rekindle the joys of looking; they bountifully reward extended periods of fascinated goggling. at

Focussing primarily on works made between the 17th and 19th centuries, the show is primarily made up of paintings (most of them anonymous) from the feudal courts of Rajputana, the region of northern India (closely overlapping with today's Rajasthan) where Hindu warrior-kings resisted the Muslim rule of the Delhi Sultanate until its fall at the hands of the Mughals in 1526. Under the Mughal Empire, the Rajput courts often retained substantial independence. They achieved this mainly through negotiation and diplomacy, but in the case of the Mewar region (in the art of which the exhibition is particularly rich) peace with the Mughal Empire only came after 40 years of guerrilla war. When they eventually downed their weapons, the Mewar maharanas, like the rulers of other Rajput courts, devoted themselves to becoming connoisseurs of life's pleasures and enthusiastic patrons of high culture, including, importantly, painting, which they commissioned to reinforce their royal prestige, document their refined lifestyles and evince their religious devotion.

Despite the fiercely independent cultural identities of these Hindu kingdoms, the distinctive Rajput style of miniature painting owes a great deal to Islamic art. Persian illustrated manuscripts first entered India during the Delhi Sultanate, the sultans brought over Persian artists to head their painting workshops, and Babur, the founder and first leader of the Mughal Empire, himself from modern-day Uzbekistan, brought with him Persian court painters. Especially after peaceful agreements between the Mughal Empire and the Rajput kingdoms were achieved, Persian influence resulted in a profound mixture of the decorative schemes and formal precision of Persian art with the riotous colour and local conventions of Indian Hindu art.

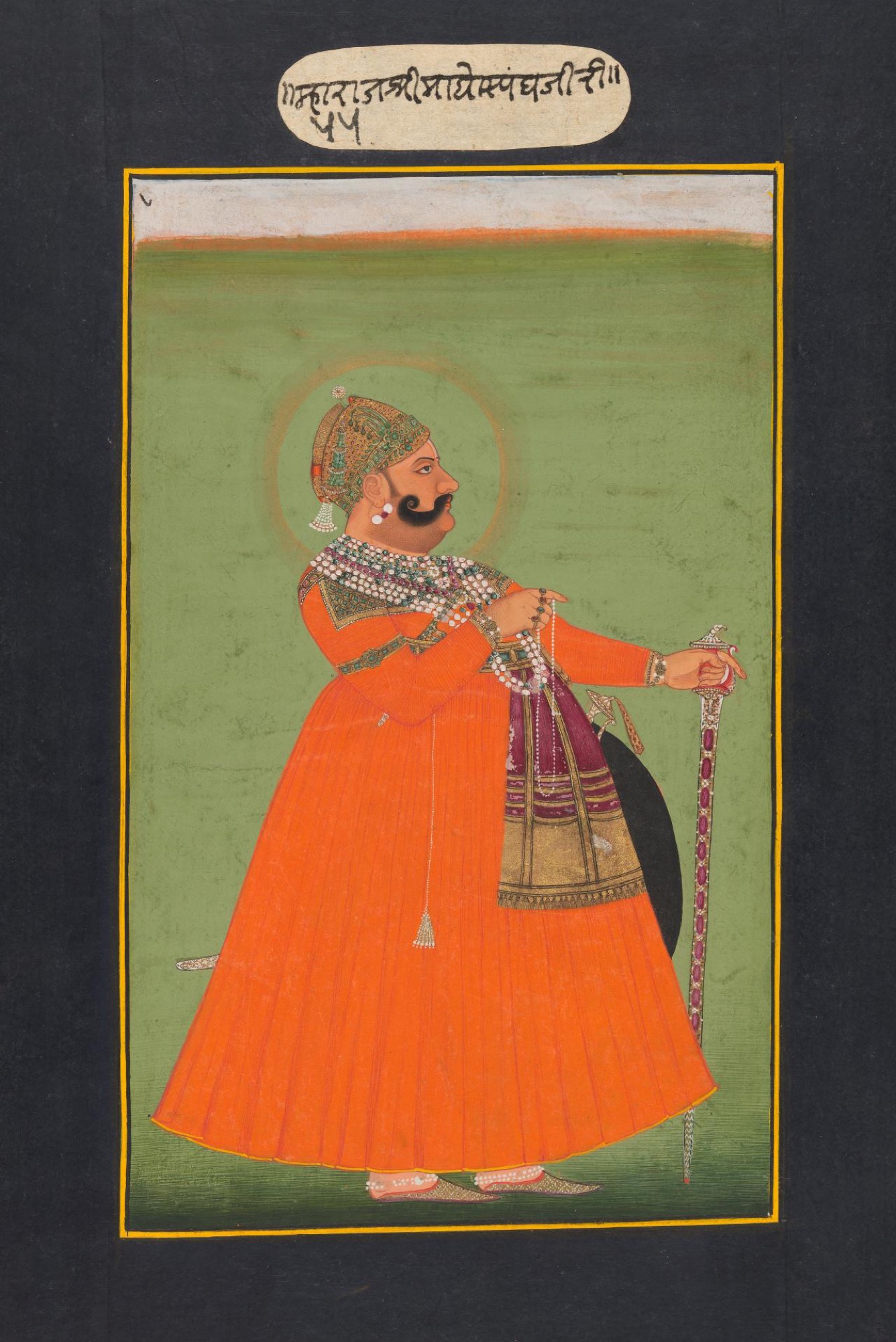

One of the key innovations that the Persian artists brought with them was the practice of individualised portrait painting, essentially unknown in India until the Mughal period. Judging from the rich selection of royal portraits on display in the show, Rajput leaders took to commissioning portraits with gusto. Most of them are full-body profile views of the king set against a large monochrome expanse, often of a luminous, sometimes almost sour green. A thin horizontal band along the image's bottom edge represents the ground on which the figure stands (or above which it floats, in one odd example). Sometimes this area contains precisely detailed grass and flowers; in other works, it is a loosely brushed smear that fades seductively into the large patch of colour above it. Within a firmly entrenched set of conventions (the king, for example, is almost always shown holding both a weapon and a small flower, a symbol of aesthetic refinement), the portraits also leave room for individuality – both in the appearance of the subject (after a while spent in the exhibition, viewers no longer need the wall labels to help them identify the distinctive visages of Maharana Jagat Singh II (1709-1751) and his male relatives) and in the artists' treatments of them. Even an element as simple as the relative size of the figures in relation to the expansive colour-fields of the background proves remarkably varied from one work to another.

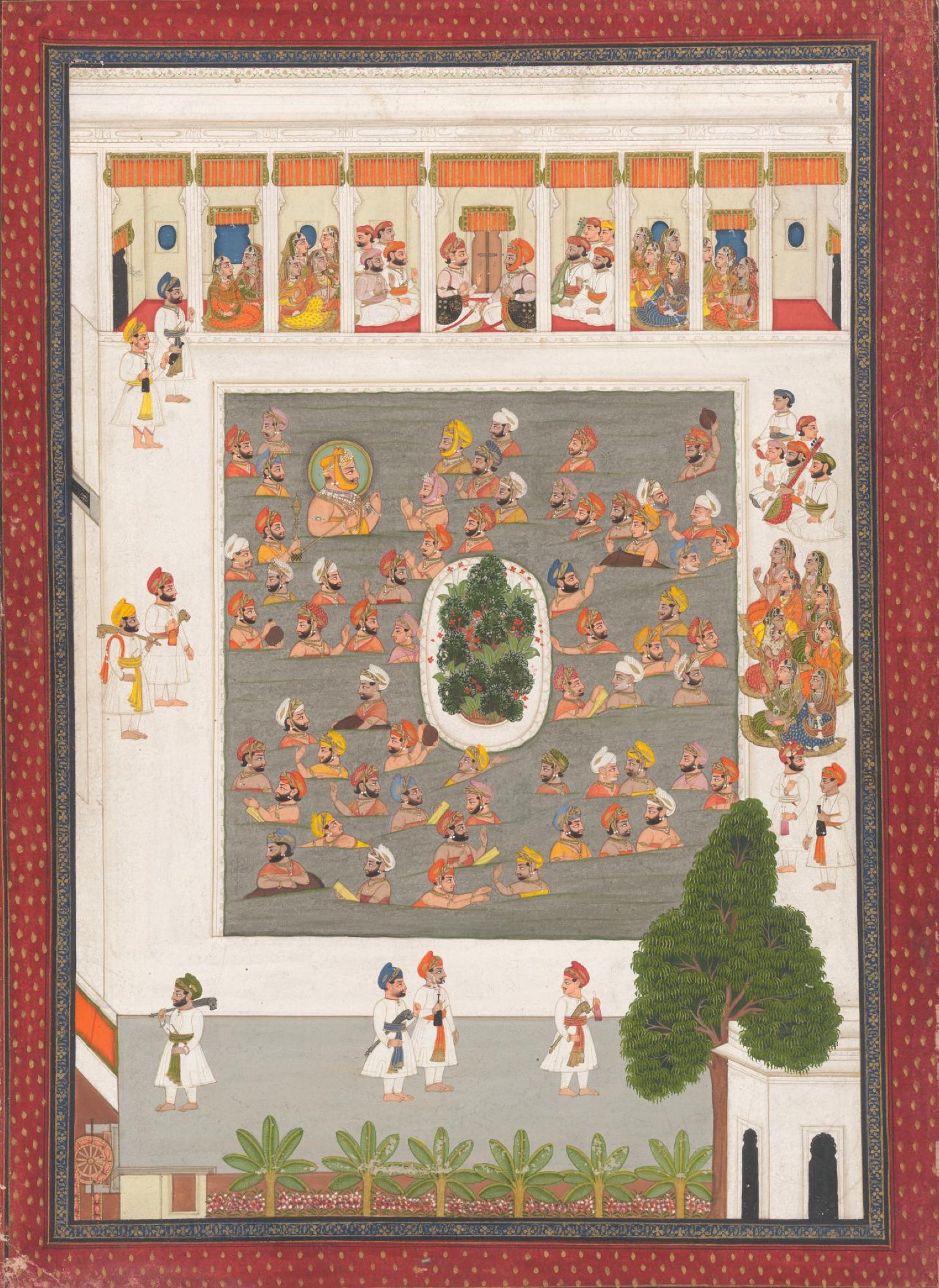

Individuality, somewhat unsurprisingly, appears to be the preserve of kings, princes and other male courtiers of the highest ranks. As an essay in the exhibition catalogue points out, female figures in Rajput art are generally idealised and non-individualised, perhaps because elite women in these societies were confined to internal palace complexes called zenana, inaccessible to all men except husbands and close relatives. Lower-ranking courtiers also seem to be represented most often in generic terms, differentiated from one another by minimal sartorial differences primarily for visual effect but often indistinguishable in facial appearance – sometimes with hilarious results, as in the comical painting (1835) of Maharana Jawan Singh bathing with his sardars (chieftains), their dozens of near-identical torsos bobbing around their enormous leader, or in the uniform expressions on the faces of the entourage helping Maharana Jagat Singh II pursue an escaped elephant in a painting from 1746, none of them seeming particularly concerned by the incident.

These incident-packed depictions of court life, often substantially larger than the royal portraits, are one of the major innovations of Rajput art. Known as tamasha (spectacle), they show kings out hunting, participating in religious festivals, enjoying various leisure pursuits (playing cards or polo, listening to music) or hosting dignitaries from neighbouring kingdoms at elaborate feasts. The teeming multiplicity of tiny figures and the distant, elevated perspectives from which they are presented these scenes reminds one at times of Breughel. But where the Dutch artist presented a vision of humanity grounded in peasant life and embracing everything from social ceremony to defecation (sometimes in the same painting), the Rajput tamasha is firmly wedded to the elite culture of the royal court, acting essentially as an extension of the self-presentation of the king in the royal portrait. They offer idealised depictions of a style of life itself already ideal. The hedonistic focus of these images appeared morally reprehensible to many British colonists, who viewed them as evidence of a decline into decadence. Really, they document a moral code quite distinct from the Christian tradition, one in which the attainment and refinement of pleasure (kama) is recognised as a value of equal standing alongside moral rectitude and material gain. In the attention and detail they lavish on the props of this world of pleasure – on flowers, food, jewellery, musical instruments, fabrics, pets, fabrics – the painters do not simply represent the life of the court in idealised form, but appear to embody its moral code, its basically aesthetic approach to life as an immersion in material things.

Akbar, the third Mughal emperor (1542-1605) collected European religious paintings, and by the late 16th century European art was already widely disseminated in India, primarily in the form of prints. (Of course, the interest and influence went the other way too: late in life Rembrandt made sketches after Mughal paintings). While the techniques of aerial perspective are present in the backdrops of many of the hunting scenes, many of the action-packed tamasha paintings present the viewer accustomed to European perspective with fantastical spatial tangles. An incredible late-17th century painting of Diwali celebrations in the palace of Kota carves its surface up into areas using distinct systems of spatial representation: while the mountainous backdrop uses aerial perspective, parts of the palace garden are shown in a bird's-eye view, while others areas adopt forms of isometric projection, creating a unstable, slippery space over which the multitudinous human figures wander without a care. Similarly, a painting of Maharana Sangram Singh II watching crocodiles being fed (c.1720) takes place in strange mixture of bird's-eye, isometric and flattened profile views, the crocodiles improbably large and an empty pavilion looking like it is about to tip into the lake. Looking at these stitched-together surfaces made up of distinct spatial systems, one can't help but wonder whether this puzzling multiplicity might not have been one of the features in them that appealed to the visual sensibility of viewers at the time.

The exhibition is accompanied by a magnificent catalogue that reproduced the entirety of the 1980 Felton Bequest works, including many not in the show. The exhibition itself is a bit cramped and rather light on wall text and, while this focuses attention on the visual delights on offer, some information on specific works wouldn't have gone amiss. But these are minor quibbles: few exhibitions on display in Melbourne at the moment can match this one in terms of the quantity of visual pleasure contained in each square inch of painted surface.

Francis is a writer and musician from Melbourne.