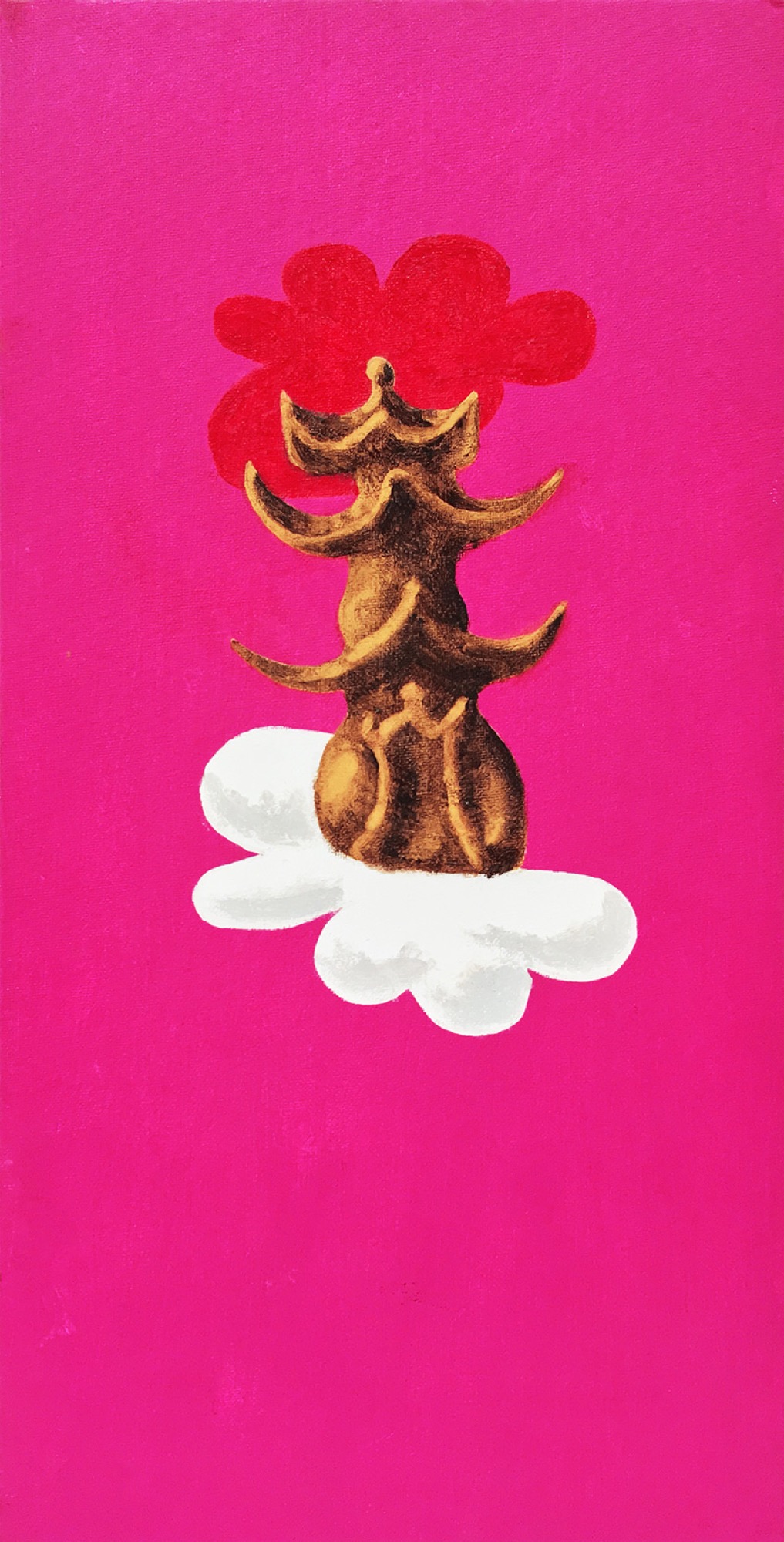

Tony Clark: Chinoiserie Landscape 1987 - 2017

Francis Plagne

Paul Taylor’s famous ‘Popism’ manifesto of 1982 included an exhortation to Australian artists to embrace the gulf separating them from the traditional centres of Western art history, to craft an art ‘born in mediation, gestated within the camera, where things are naturally upside-down, and expressed in a carnivalesque array of copies, inversions and negatives’. The same year, Tony Clark held his first solo exhibition, at John Nixon’s Art Projects in Melbourne, consisting of a series of modest, sloppily painted canvas boards depicting classical architectural and sculptural motifs arranged along a wooden shelf under the elusive title Technical Manifesto of Town Planning. To some, Clark’s work seemed the perfect embodiment of Taylor’s ideas, seeming to delight in its own poverty, in the comic mismatch between the grand traditions to which it referred and the amateurish, haphazard nature of its painting. This tension is perhaps at its most pronounced in the Sacro-Idyllic Landscapes of 1983, which reduced the twin tropes of classical landscape painting (classical architecture embedded in idyllic nature) to almost pathetic smudges set against monochrome grounds.

Similarly, Clark’s most famous project, the Myriorama series (begun in 1985, to which the artist continues to add) deliberately strips the tradition of landscape painting of its aura. Inspired by a game created by John Clark in 1824 in which 16 cards representing aspects of a landscape, each with the same horizon line, can be combined to create (according to John Clark’s own calculations) 27,922,789,880,000 different views, Clark’s Myriorama paintings use the same technique of matching horizon lines that can be used to connect any number of individual panels into a larger scene. Clark thereby applies the serial logic of minimalism and pop art to the hallowed genre of the landscape, questioning the role played by convention and formula within a genre that has often been admired as exemplifying the artist’s attempt to catch a pure glimpse of nature outside of culture and habit.

However, as Graham Forsyth noted in an insightful essay on Clark published in 1997, the view onto Clark’s work provided by the lens of postmodern irony is only partial. For, as much as Clark’s continuous rearticulation of classical tropes in his work seems calculated to take the measure of his distance from them, his paintings also seem to invoke classical traditions as ‘homages to a continuing source of inspiration’. In Clark’s own words: ‘Irony is a subordinate element in the project. It is part of the structure of the work, part of the initial set-up, the machine. By having it there in that way it then leaves me free to develop an attachment to the imagery, and see what I can do it with it, where I can take it. It leaves me free to discover that “I love this stuff”’.

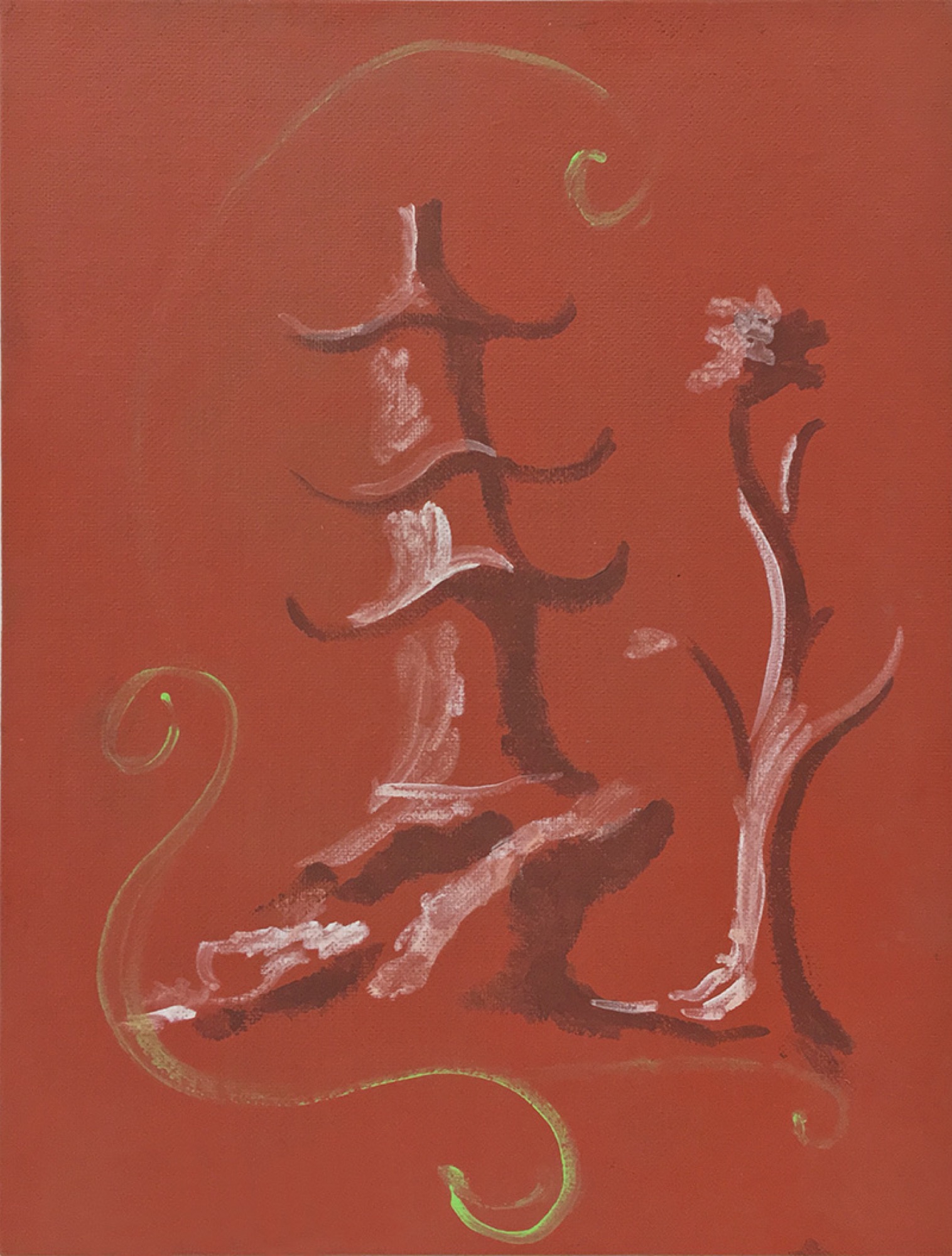

This notion of ironic distance as a freeing space of creative possibility is borne out to some extent by the exhibition of Clark’s Chinoiserie paintings currently on display at Murray White Room. Rather than being directly inspired by east Asian art and culture, Clark’s Chinoiserie works draw on the European fad, which reached its highpoint in the 18th century, for art, architecture, and decoration making use of Chinese imagery and aesthetics, often combined with influences from India and the Near East in a catch-all form of exoticism that licensed some of the most gloriously excessive decorative impulses of the Rococo period.

Most of Clark’s Chinoiserie paintings (the majority of which were produced in the late 1980s and all of which are generically titled Chinoiserie landscape) feature a stereotypically Chinese pagoda, a common feature of many 18th century European gardens in the ‘Chinese’ style. However, rather than being painted from photographs of surviving structures or historical depictions, Clark’s paintings are in the main depictions of rudimentary plasticine models made by the artist himself, a process that, somewhat paradoxically, both further emphasises Clark’s ironic remove from his subject matter and brings this series of works close to the tradition of the studio still life. Clark works up a variety of styles of image from the simply motif of the pagoda (often accompanied by trees): slapdash works on board or paper that place the pagoda against monochrome backgrounds; pieces that seem inspired by enamelware designs, depicting the pagoda in wispy arabesques; more polished works that model the plasticine figures naturalistically against arbitrary decorative backgrounds that take on the appearance of wallpaper or linoleum floor tiles. As this variety of styles and manners shows, Clark himself says, his interest is less in the clichéd imagery itself than in finding out what he can do with it, where he can take it.

Yet, despite the variety on display, the impression that the exhibition makes overall is somewhat dull. Despite Clark’s insistence that his work is not a sort of theoretical demonstration of postmodernism, at times the work fails to compel as painting. Many of the more decorative pieces, for example, are more interesting for the questions they drag up about hierarchies of taste than in their own somewhat underwhelming, mannered appearance. Equally, the inoffensive nature of much of the exhibition reminds us that Clark’s work, for all its questioning of the tradition of the picturesque, also makes itself available for use as simply one more, degraded instance of this tradition – as evinced by the reproduction of one the Myrioama panels on the cover of an issue of Reader’s Digest and, perhaps, depending on how much irony one wishes to ascribe to Malcolm Turnbull, by the conspicuous presence of several panels from the series in the current decorative scheme of the Prime Minister’s office. (Of course, given Clark’s commitment to unsettling the boundaries between the high and the low, this ambiguous other life of his paintings is a sort of triumph for Clark.)

The most satisfying paintings in the show are the most casual and seemingly throw-away, such as a lovely 1990 work in acrylic on black paper that, like a sheet of studies, shows two half-finished versions of the same scene amid a messy cloud of brush strokes. Like Clark’s earliest painting, this and other similar pieces in the show quite effectively bring the viewer’s efforts to form a coherent representational image out of a mass of painterly marks to the forefront of the experience of the work, prompting a depth of aesthetic engagement that, paradoxically, the more traditionally polished pieces in the show fail to inspire. These pieces also remind us that part of Clark’s importance for many of the Melbourne artists who encountered him in the 1980s (such as Geoff Lowe and Angela Brennan) was to be found in the attitude of punk irreverence of a self-taught artist who was known to paint using a head of broccoli as a brush. In Geoff Lowe’s words, ‘what was fantastic was that he didn’t try- because the history of art is full of so much trying’.

While some of the work on display at Murray White Room might not be Clark’s most exciting, the show certainly serves as a reminder that the last large retrospective of the broccoli maestro’s work, curated by Max Delany at Heide in 1998, was held twenty years ago; another one, bringing us up to date with the last twenty years of Clark’s elusive production, would certainly be a valuable contribution to the landscape of contemporary Australian art.

Francis Plagne is a writer and musician from Melbourne.

Title image: Tony Clark, Chinoiserie landscape, 1987, oil on canvas board, 30.5 x 68.5 cm, triptych.)