What does it mean to live inside the present? This is the question Clarice Lispector is asking in Água Viva (Living Water) (1973), a text that grabs on to the present—the instant-now—and never lets go. “I want to possess the atoms of time,” writes Lispector, and Água Viva is a novel where there is no past or future, where we are always in the soup of action and event. It is an exhilarating and dazzling saga composed entirely of fragments, an episodic volume where language itself is often on the verge of disintegration. “The instant-now,” says Lispector, “is a firefly that sparks and goes out, sparks and goes out.”

It is this type of continuous present, the here-and-now of the firefly, that Tom Blake is occupying in his latest solo show, holding leaves (index.), now on view at N.Smith Gallery. Drawing on Água Viva, this sophisticated and assured exhibition extends Blake’s ongoing preoccupation with the experience of time—how we can hold onto, and collate, fragments, associations and memories.

index / silt (2018-2022) may be the first or last piece you see in the exhibition, depending on whether you’re the kind of person who goes straight to the main event or the kind of person who pauses on the threshold. For this work, Blake has placed two companion iPhones on the top left quarter of a nondescript wooden door at the entrance to the gallery. Each screen shows a looping video of the final seconds of the 1986 film The Beekeeper—there is a panning shot of blue sky, then a momentary swirl of bees, before the video repeats. Ostensibly, the two screens are showing exactly the same instant-now and yet, over time, their frame rates diverge. As the loop begins to go out of sync, we start to see multiple instances within instances, an echo moving from one screen to the next. But, if you watch the videos for long enough, you will discover that the loop starts to realign once again. index / silt is the only moving image work in the show, and its clever placement as an entry/exit piece allows for a compressed version of Blake’s overarching themes, a kind of exhibition-in-miniature.

In the main space of the gallery, Blake has intervened to create a room within a room. An installation made up of large white paper sheets, each covered with an intricate mass of fine lines, serves to create a set of dividing walls, windows and doorways. The paper sheets are held together with tiny circular weights, but they are light enough that a gentle movement of air will cause the walls to rustle and sigh. The sheets work as a form of shroud or veil, covering the gallery in a cascade of falling lines or, as the show’s title suggests, what we might take to be falling leaves. Each leaf then becomes a metaphor for an instant-now—the individual strokes, ticks and curls on the paper a record of fleeting moments.

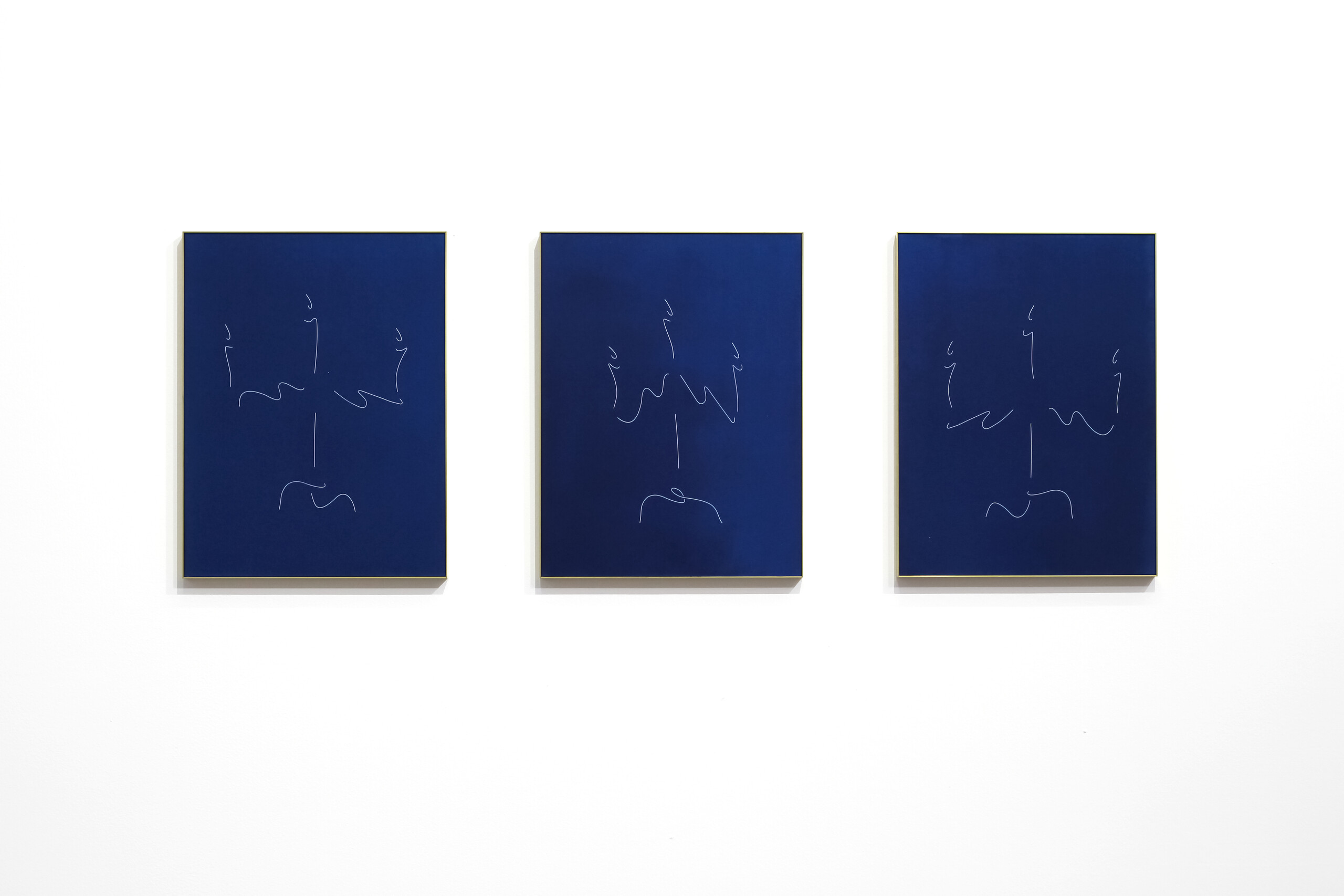

Set amidst this cascade, whether in the L-shaped hallway created on one side of the partition, or in the smaller room on the other, are a series of cyanotypes. (Part of the challenge of writing about Blake’s work is how it refuses fixed descriptors—these are also drawings, etchings, sculptures and spatial interventions.) Holding (loop/index) (2022) depicts the barest outline of a hand attempting to grasp a thin string or rope, with an elegant loop skirting at one end, while constellations (holding leaves) (2022) features a scattered set of pinpricks that may be seeds or stars or dust.

Alongside these, and dispersed across the space, are Blake’s de-silvered mirrors, works that engage in their own form of interplay, at times reflecting the walls of the gallery, the other works or the dividing paper walls. Each of these mirrors has been hand-etched, with Blake scoring lines into the back of each panel so that when they are lit from behind, they appear as if made from light. Stand back and you may see the outline of an image (a chair, a shelf or a leaf). Look again, being mindful to attend to the spaces between the lines, and the coherence of the image ruptures. Look once more and you will not see lines at all, just your own reflection staring back at you.

The present-ness of Lispector’s Água Viva seizes you by the throat and pulls you straight into her stream of consciousness. At times, this feels disorientating and dangerous; the present is not to be taken lightly. Lispector finds hell and blood and bats in her instant-now and, although it is not so overt, an element of disquiet does start to creep into the edges of holding leaves (index.) too. The falling lines, like leaves, can begin to close in around you, can start to shift from calm backdrop to chaotic overlay and, try as you might, you can never escape the presence of your own image in the mirror. Then there is the way Blake controls our movement through the space, greeting us with a wall rather than an open gallery, or directing us to kneel down to see a loop of light projected onto a skirting board. There is the queasy never-ending groundhog day of bees and blue sky.

What gives holding leaves (index.) its depth, this sense of fragments spiralling outward or changing shape depending on your point of view, is Blake’s poetic sensibility. I don’t mean “poetic” as an adjective for a romantic or melancholic sentiment, rather “poetic” as in attuned to the formal conventions of poetry. That is, there is an overlap in the way Blake conceives of the shape of a line and how its meaning is generated, with how a poet deploys line breaks, caesuras, rhyme and repetition. Just as the line break in a poem can act as a hinge—the moment of a breach or a rupture—so too do Blake’s drawn curlicues open a breach where we can let our imagination drift. The most successful works are the loosest, the ones (like holding light (three instants) I-III (2022)) where it is difficult to collect the lines into a coherent, figurative form.

Such a generous and open-ended approach to meaning-making means the objects of holding leaves (index.) never fall back into the past tense. Each time a new viewer enters the gallery, or when the same viewer returns in a different mood, the process of holding and (re)assembling the fragments and instances begins anew. That is to say, what keeps animating Blake’s exhibition, perhaps long after you have seen it, is the jostling, the hustling, the jingle-jangling of all these different subject positions, of all the presents we can occupy simultaneously.

Naomi Riddle is a writer, musician, and the founding editor of Running Dog.