Vito Acconci, Face-Off (1972). 00:32:34, black and white, mono, sound. TMI exhibition installation view, Cement Fondu, 2024. Photograph: Jessica Maurer.

TMI (Too Much Information)

Laura Luciana

TMI (Too Much Information) traces a history of video art and its tendency towards confession from 1972 to the present. Of course, video art has changed a lot between now and then. The intervention of digital communication in our daily lives, and the online cultures that have since been cultivated, are threaded throughout TMI. As I trudged up the polished concrete stairs of Cement Fondu, Vito Acconci is already trying to get under my skin: “We haven’t even said hello yet?” With the artist’s body as instrument and the screen as the display, the audience is positioned less like a participant in a conversation and more like an unspeaking priest on the other side of a confessional booth. In her 1976 essay “Video: The Aesthetics of Narcissism,” Rosalind Krauss likened the video work to a mirror. Krauss’s critique of Acconci’s work, that the artist is often exploiting the medium to “criticise it from within,” resonates with contemporary critiques of the confessional mode. This reflexive and narcissistic relationship to the screen, for Krauss, delimits the medium’s critical potential. But there is something beautiful about the insight gleaned from looking at someone else’s reflection in the mirror. TMI gazes upon the compulsively confessing artist with this kind of romance.

Upstairs, in the gallery, the space is cacophonic and competitive. The mediating technologies of post-digital communication are all there: phone screens, video essays, desktop computers, and artists and avatars talking to camera. A computer background swallows me into the screen—vast and sprawling—with the colours of a sunset and an aurora borealis. CLOUD_COPY_UNREQUITED (2024) by Xanthe Dobbie transposes this screen across an entire wall of the gallery. The space is filled with contemporary interfaces of self-expression spilling out words and vocalisations everywhere. “No, no, no, no, no, no, no, no,” Acconci cries in the middle of the exhibition space from what looks like an old cathode ray tube (CRT). If I was an attention economist, I would be worried that the romance was getting lost.

Xanthe Dobbie, CLOUDCOPYUNREQUITED (2024). Phototex digital wallpaper. (Commissioned by Cement Fondu, 2024). TMI exhibition installation view, Cement Fondu, 2024. Photograph: Jessica Maurer.

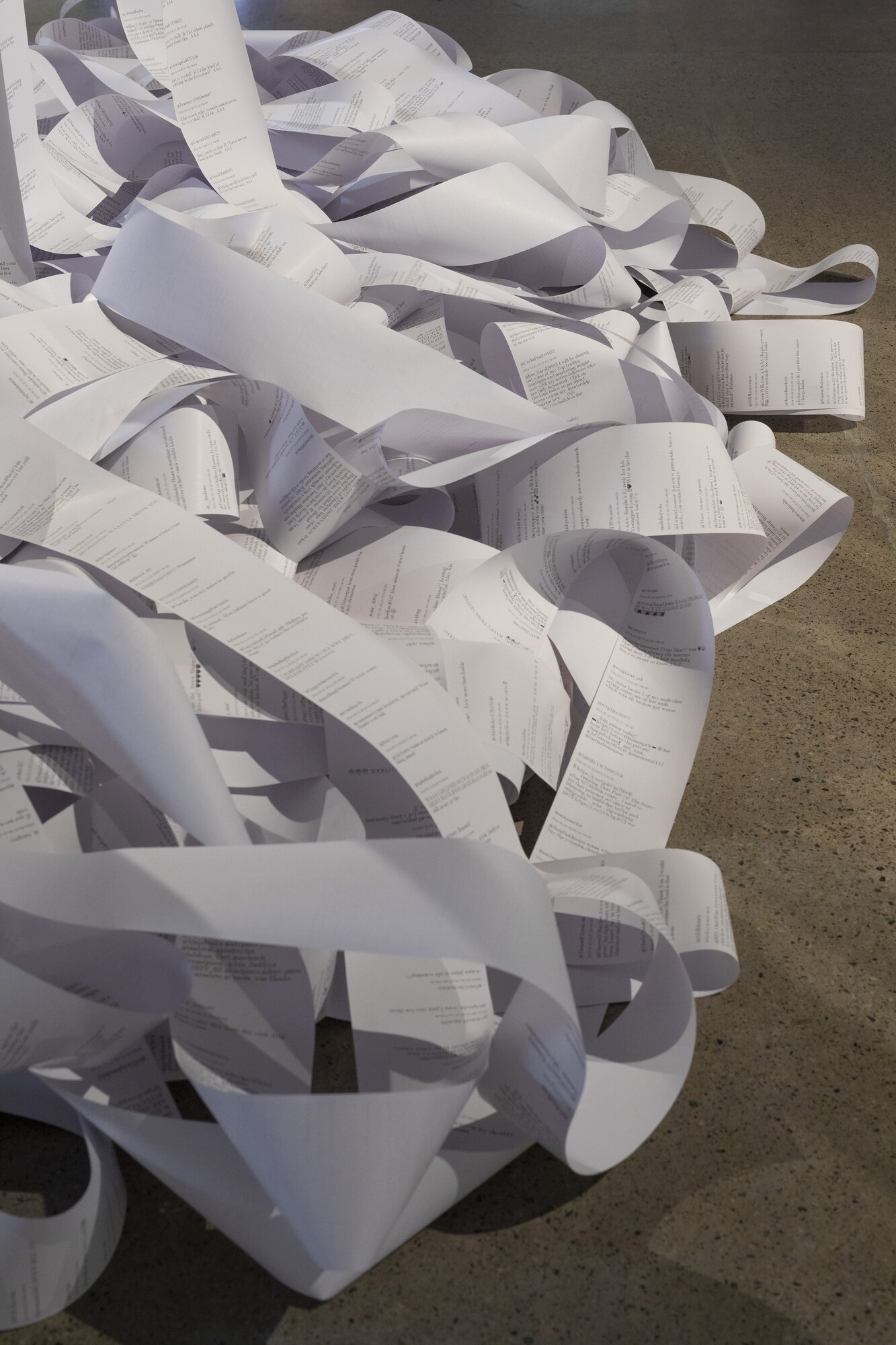

Above me, constant streams of words, stamped with metadata, times, and usernames spit out of thermal printers (more commonly used for printing receipts) from the sky. Christopher Baker’s Murmur Study (2009 to present) collates micro-messages like Facebook statuses and tweets, printing them as ceaselessly as they are posted. Where the ribbons of receipt paper collect on the floor are tweets from yesterday and the day before. They don’t look like my algorithm because I see some about sport. But they do look like my algorithm when I recognise a reply to Anna Khachiyan. A 2009 video of Murmur Study online feels more optimistic. Posts like “i hate cleaning my room! but at least i have band practice soon :)” convey something more innocent about the goal of online communication. I’m worried, because, in contrast, there’s something nefarious about the bitcoin scam tweets that are being printed into the doomscroll of posts pooling on the floor. I wonder what the potential recipe is to trigger my tweet to be printed, or what information is missing from my X dataset that could show me the perfect tweets to keep me scrolling. Seeing the doomscroll (usually contained in the phone) materialise in the gallery really looks like “too much information”—too much information being compulsively excavated by online users posting, too much information that we ingest by being “chronically online.” The confessional impulse in Baker’s work is outsourced to users who don’t know their spam, outrage, or intimate thoughts are being printed which within the context of TMI feels like absolution.

Christopher Baker, Murmur Study (2009-2024). 24 thermal printers, printer paper, custom software. TMI exhibition installation view, Cement Fondu, 2024. Photograph: Jessica Maurer.

If you’re getting distracted, thankfully there are phone screens to look at in the exhibition. Benjamin Forster’s delightful Ghosts (2013) is displayed on tiny pairs of old Nokia phone screens that appear to be texting each other. I take a video of one sappy and banal exchange and send it to my best friend. “This is how we text each other,” we say. I record an exchange on another pair of Nokia screens, dated 16 January 2012, and send it to the appropriate recipient in my contact list:

“…sex kitten! I love you miss you wish you were here!”

“I miss you too baby face, I want to kiss you HARD xxxxx”

“We should have had sex before I left! :( I wanted too (sic)”

“Yeah, we were just too tired right? We will have amazing sex when you get back!!”

Ghosts and Murmur Study concern themselves with the semantics of digital intimacy: timestamps, emoticons, idiosyncratic punctuation. Thankfully, I have the immense interpretive imagination only accessible to the obsessive, so I am moved by the romance of the sexting Nokia screens. The reckless affection embedded in online-speak makes TMI for this sensitive type. As I continue to watch the phone screens sext each other, an extraordinary propensity for daydream diverts my gaze to my iPhone messages. I think about an essay by Dandi Meng called The Confessing Image, which characterises the potential poetry of metadata in screenshots as reckless, fast, ubiquitous, and ephemeral. I’m almost certain the reckless endlessness of posting has more risk of getting lost rather than found. It seems that way, watching dates appear on screens and usernames spit onto piles of endless receipt paper.

Amalia Ulman, The Annals of Private History (2015). 14:07, video, sound. TMI exhibition installation view, Cement Fondu, 2024. Photograph: Jessica Maurer.

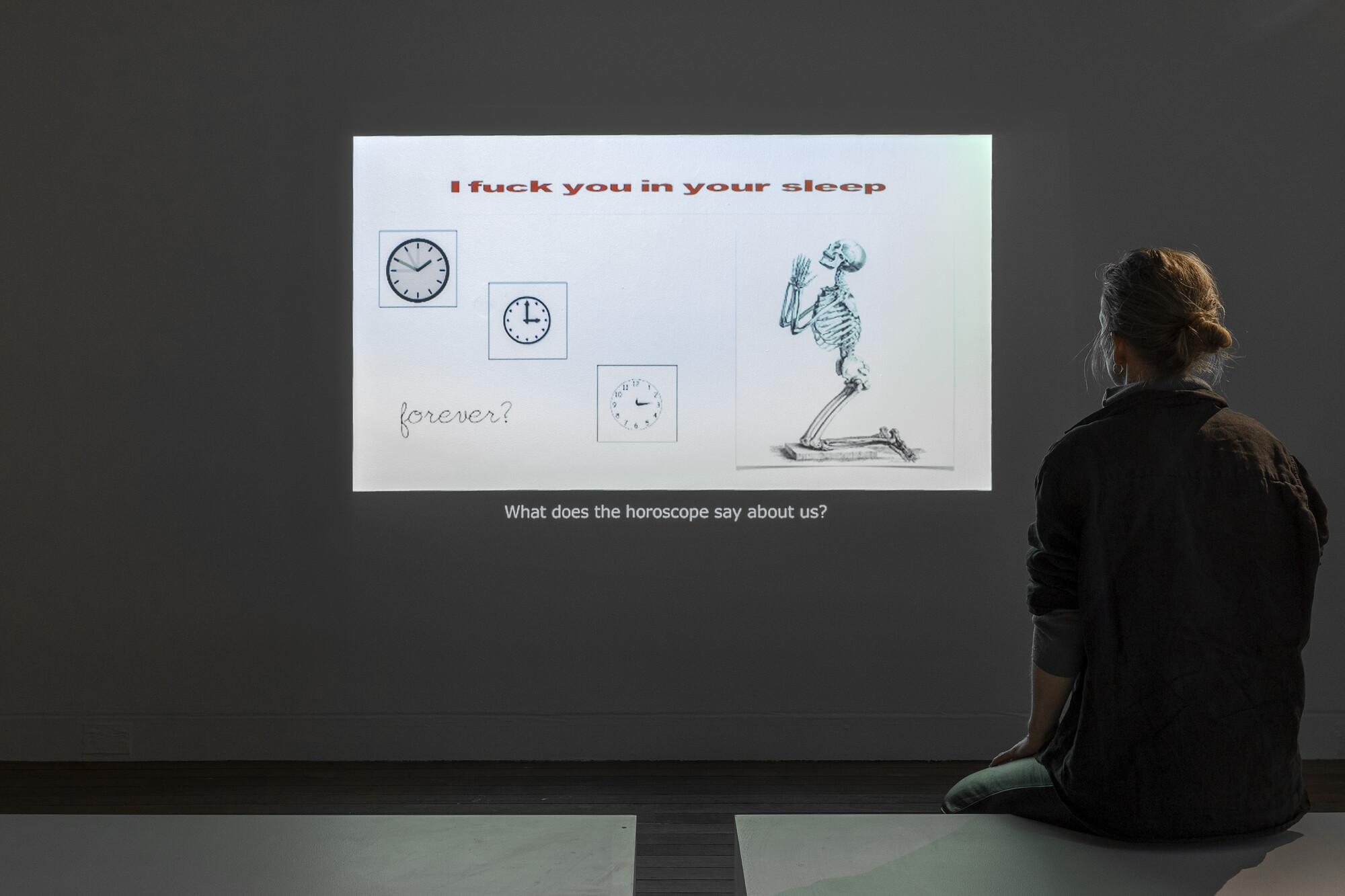

The Confessing Image also attempts to reconcile the role of excessive online sharing in the feminine confessional genre that permeates other works in the exhibition, like Erica Scourti’s Life In AdWords (2012–2013). To the webcam, Scourti recites the AdWords Google suggests in response to their daily Gmail diary entry. It reflects only fragments of what was divulged. But what if the private life these works contain is an invention? The Annals of Private History (2015) by Amalia Ulman narrates a history of the diary. She addresses you like a lover that she wants to terrorise. The feminine voice of the narrator teases you, the audience, the voyeur, the pervert, peering too closely into the private thoughts of the artist. How much information is too much information for you? “I didn’t mean to offend you!” one slide of the video disclaims. The oldest diary Ulman traces is to a thirteen-year-old girl with gonorrhoea from her uncle. It’s suggested that the sexual violence and subsequent illness that she endured then required the privacy of the diary to unfold its pain. We have her to thank for the heart shaped lock on diaries for little girls. This gives way for Ullman to collect opening lines from vlogs of women broadcasting their vulnerable life events: transition and hormone therapy, pregnancy, liposuction, and “what your first blog post should be about.”

The problem of confession, in the form of the personal essay, has been approached in critical writing and in clickable, Instagram sharable Jia Tolentino style essays. Naarm’s own Sally Olds, author of People Who Lunch (2022), attempts to reconcile it once and for all in The Beautiful Piece by tracing a history of the hybrid essay and a potential formula to make or deconstruct the form by its components: theory, analysis, and personal experience. The self-confessional form has also been characterised by Felix Bernstein as irreproachable. Perhaps our problems with the confession and the personal are less an issue and more an irritation. Clearly there’s a persistent desire to express something about artist’s interiority in the context of a collectivity, a public, an audience. Should we avoid Frank O’Hara’s “friend-to-friend tone of gossip over academic formalism?”

Brian Fuata, Story Sent (2024). Email performance. (Commissioned by Cement Fondu, 2024). TMI exhibition installation view, Cement Fondu, 2024. Photograph: Maria Boyadgis.

A clue might come in the form of Brian Fuata’s Story Sent (2024). This is just one of the five new Australian commissions for TMI. Fuata’s email performance functions similarly to previous iterations like From: To email performances (2021). TMI and the rich—and potentially crass—inner worlds of its artists are not just contained within the exhibition, or in video; it is also direct-to-inbox. We are invited to exchange with Fuata’s intimate stories in a way that feels entirely private, until you are gathered into the space for the live performance. Subscribers to the email list receive Fuata’s charming and seemingly compulsive dispatches prior to the performances. One such story sent describes a public sex encounter. Addressees are encouraged to reply; it’s all very iPhone-to-iPhone, or friend-to-friend. I’ve been printing collages of lesbian porn with crappy poetry on receipt paper at work, so I make one for Fuata and send it. He responds with a screen recording of my message with suspenseful music on top. There’s something potentially unnerving about the suspenseful music, about the intimate nature of his confessions, about the potential audience participation in his live performance. After all, how much is too much?

On a second visit to TMI, I arrive at the gallery just in time for Fuata’s second performance. For twenty minutes, as if channelling a divine lyric from the ether (or rather, ethernet), he stutters into the mic, and I transcribe and video him. Seeing him live, unlike the flatness of the mirror or the screen feels like catharsis. Performance has the romance of being seen and done just once, for the devotees in the room. And it has the titillation of Fuata saying vulgar words, whisking around an audience member and muttering about masturbation. It’s as if this divine lyric that he is channelling were from a Peaches or Madonna song:

“Jack Jack Jack off …. and it was one of the most beautiful sexual moments I’ve had in my life…

“I love pop music, it’s a good container to express how you feel…

“I love breakfast, açai, fruits,

“Cum cum cum cum

“I have cum for breakfast

“I have cum for breakfast

“Semen and salt…”

The monologue is about as edifying as some books I have read. It’s certainly better than TikTok, because the word “cum” would probably get censored on there. And if that’s a little too much for you, then be glad you’re not on the receiving end of Story Sent. I urge you to attend, even if it is too late to join the email list.

Laura Luciana is an artist and writer on Dharawal and Gadigal land. She is currently undertaking Art Theory Honours at UNSW A&D and thinking about talking, creative labour, and jerking off.