I noticed when researching for this review that Nicholas Mangan was born in Geelong, where I, too, was born. And, presuming that Mangan grew up there, I wonder whether he ever encountered the bizarre CSIRO Animal Health Laboratory that I lived near. Crowned with an enormous tower that, in hindsight, might have been a colossal chimney (perhaps for releasing the smoke and vapour from biological experiments); it was a bizarre site that dominated the skyline and dwarfed the buildings around it. The reason why I wonder if Mangan might also have been aware of this building is because the constant visual presence it had in our lives—and simultaneously its barring of access—made me, at least, desperate to know what went on inside. It also caused me to develop narratives of all the weird and science-fiction-like experiments going on in the laboratories. Indeed, when I heard that my sister’s friend had been employed to feed the health laboratory’s HIV-infected monkeys, my suspicions about the deviant experiments going on behind closed doors were only exacerbated.

Mangan’s current exhibition at Sutton Gallery, Termite Economies, takes as its starting point a particular experiment run by the CSIRO in 2008, where termites were thought capable of being trained to lead researchers to gold. The experiment ultimately failed. A failed experiment that never truly came to fruition, stagnated in time and, therefore, is also full of potential. With little details of the actual experiment and no concrete outcome, the artist is able to explore the event through a nexus of memory and imagination. Mangan ruminates on what might have been, looking back in time to project an image of the future onto the present moment. In many ways, this method is in line with his broader practice. His regular pairing of natural materials, such as minerals, coconuts and stone, with modern technology, for instance, consistently works to trace the arc of human existence and our ongoing fraught relationship with the natural world.

Mangan wants to hybridise. He wants to make two seemingly opposed worlds melt into one. The exhibition is comprised of four purpose-built tables with steel legs and plywood tops that sit slightly above waist height. Each table supports between one and three 3D-printed models that appear to be based on termite tunnels but have in fact been hybridised to resemble scaled down gold-mining structures. Each model is finished to look as though it is composed of earth; the dull grey plastic of the 3D printer is here is given a patina of muddy-brown dirt, trace elements of which can be seen to have ‘fallen’ from the pieces on to the tabletops below. Each model includes perfectly sliced cross sections, as though made by a drop saw, that indicate the human incursion onto the more organically shaped, insect-made object.

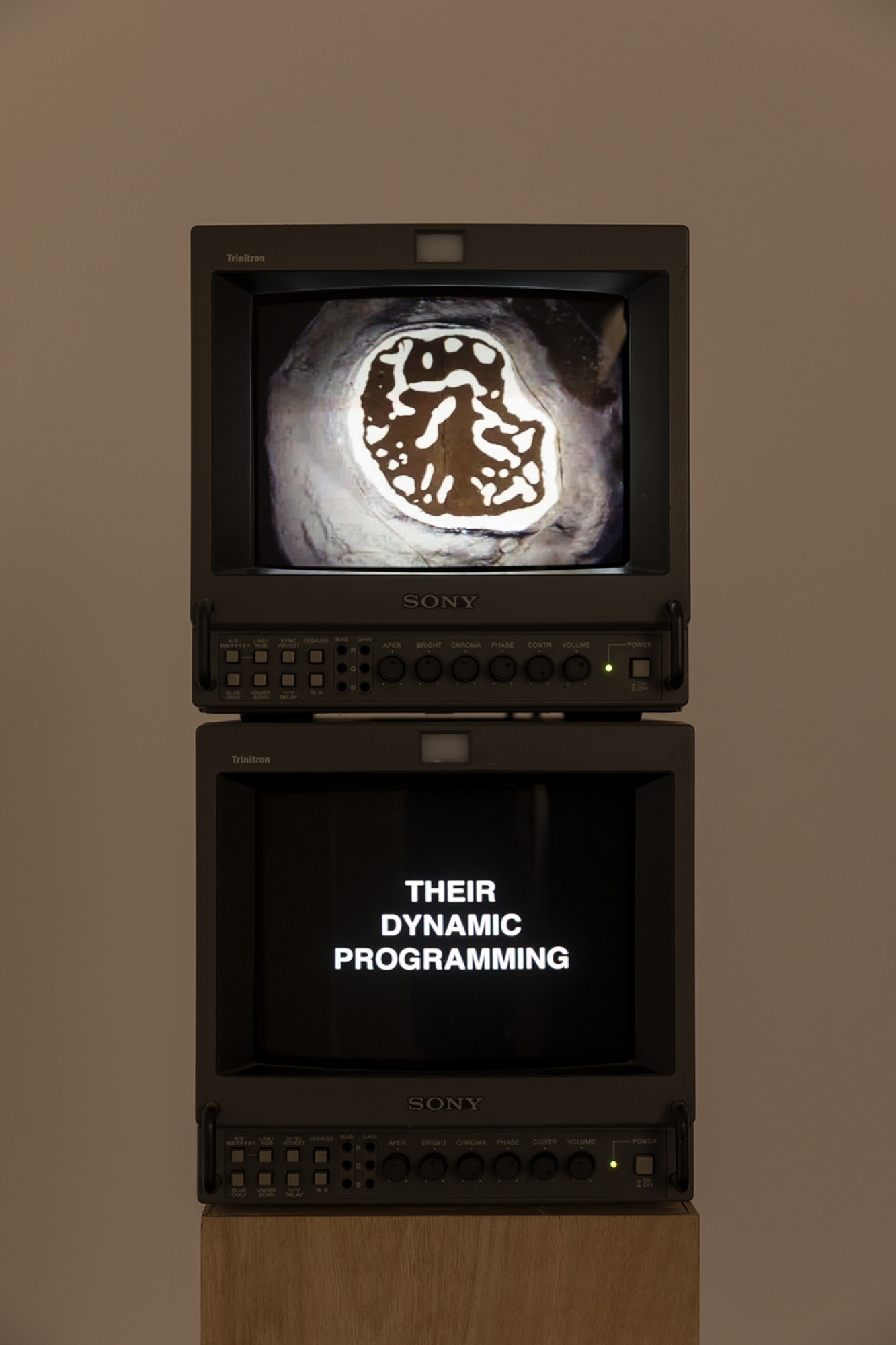

Complementing the models are a number of broadcast monitors, mounted on custom-made plinths, beautifully elongated to perfectly fit the old-fashioned screens. Various termite-related footage plays on the monitors: the insects building nests, slow panning shots of termite mounds, or close-ups of the termites scurrying around in what appears to be a petri dish. This scurrying on screen is picked up by an aural accompaniment: a rushing soundtrack of clicking, ticking and worried insect movement circulates around viewers through a surround-sound installation of speakers. The small gallery at the entrance of Sutton is elegantly installed with two monitors stacked on top of one another. The uppermost plays footage of some sort of cross-section, perhaps termite burrows, while the lower screen plays a loop of fragmented text, with phrases such as “the department coveted their labour”, with the “department” obviously being the CSIRO team investigating the termite miners. Some of the footage is archival, while other footage is newly shot by Mangan, but it is a bit difficult to know which is which. In fact, is almost impossible to decipher human-made from artificial, soil from plastic.

Indeed, the mediums and works in the exhibition form a single entity, suggesting the inability to simply separate human from animal, economics from survival, nature from artifice. Prior to seeing the exhibition, I thought there would be a binary of exploiter/exploited at play in Termite Economies. But I was wrong. The hybrid nature of the works suggests slippages rather than a simple coming-together of polar opposites. What Mangan does very well is to upset the general vilification that comes with exploitative practices, instead considering the complexity of such situations. The works as well as their presentation communicate the misconception of a term such as ‘binary’ in coming to grips with the surreal narrative. Part of his approach is to elevate the narrative to a position of fantasy: the termites are the star of the show, elevated from the role of destructive pest to tiny miner, while the scientist is nowhere to be seen. I am reminded of the Dinotopia books that depict a fictional utopia where dinosaurs and humans live and work together.

Typically, Mangan’s work is very serious. I recall a piece in his 2016 exhibition at MUMA Limits to Growth called Nauru Notes from a Cretaceous World (2010) that considered the sale of Nauru’s coral rock as coffee tables as a way of saving the island’s economy, ironically stripping the landscape of the last vestiges of its natural resources in order to save it. Termite Economies is also serious. But his imagined narrative that anthropomorphises the termite is fantastical and offers a brief alternative to the reality of the experiment that in reality was aimed at increasing human wealth. And, indeed, the whole story goes that scientists found that if small traces of gold were in the termite mound then the termites must have picked it up close by, thus leading scientists to deposits. Knowing this, the science-fiction and/or utopian allusions quickly disappear. Mangan has created a speculative narrative, just as I would speculate about what went on behind the doors of the Animal Health Laboratory. Were the monkeys being fed with a superhuman drug that would cure them of their diseases and make them immortal? No. The reality was simply a group of unfortunate primates that, due to their similarity to human genetic coding, could be used to test the abilities of various HIV medications. Similarly, the termites offered a new and perhaps cheaper alternative to current methods for finding gold. Termite Economies considers the human relationship to the earth by way of a fantasy that, nonetheless, grew from an actuality. As such, it speculates about the mental and physical lengths that people are willing to go to in order to advance, while also accepting that as an inevitable trait of humankind.

Amelia Winata is a Melbourne-based arts writer and PhD candidate in Art History at the University of Melbourne.

Title image: Nicholas Mangan, Termite Economies (detail), 2018. Courtesy of the artist and Sutton Gallery. Photo: Andrew Curtis.)