Sovereignty

Paris Lettau

Anyone familiar with contemporary art exhibitions, art fairs and international biennales might notice that Sovereignty just doesn’t quite feel like an exhibition of contemporary art. And it raises one question: Why is this?

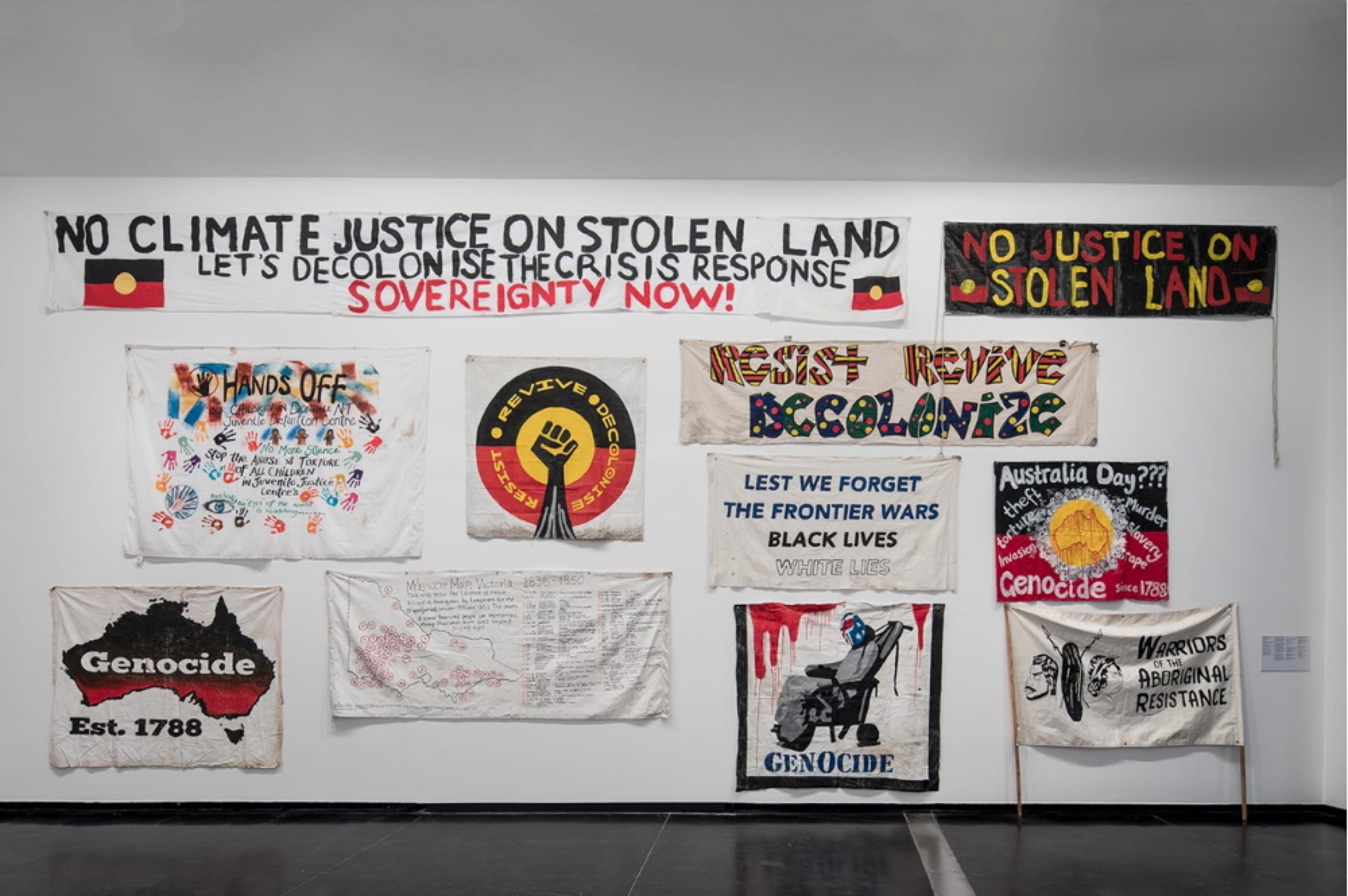

It can’t only be explained by Sovereignty’s display of cultural products that aren’t “fine art”, because contemporary art curators regularly draw on a broad cultural archive, as seen in influential biennales like Documenta 13 at Kassel, Germany in 2012. Sovereignty includes objects such as William Barak’s Shield and Club (1897), with which the exhibition begins, to the various reflections on personal identity in a series of short videos InDigeneity: Aboriginal Young people, storytelling, technology and identity (2014–16) presented by students from the Korin Gamadji Institute. The exhibition even includes a feature-length film: Amiel Courtin-Wilson’s documentary portrait of Jack Charles, titled Bastardy (2008) (which I’m sure you can watch on iTunes), is historicised alongside the first Indigenous-made film production, Bruce McGuiness’s documentary Black Fire (1972), and a montage of digitised 8mm footage from the Aboriginal cultural leader, political activist and entrepreneur, Bill Onus. Adding to the plethora of screens there’s a soundtrack as well. Entering the main exhibition space, viewers will hear the beats and lyrics of hip-hop artist Briggs (Adam Briggs) with tracks like Sheplife (2012) and his increasingly well-known track, Bad Apples (2014), displayed as slick, commercial video-clips on flat-screen TV monitors mounted to the gallery wall. Protest banners by the Melbourne-based political resistance and Aboriginal nationalist group WAR (Warriors of the Aboriginal Resistance), clearly not intended as contemporary artworks, per se, also cover the walls in the final room of the exhibition.

In fact, Sovereignty premises itself on the inclusion of a broad range of cultural products of First Nations peoples from South East Australia; or, as co-curator Max Delany states in his catalogue essay (somewhat unexpectedly adopting the territorial borders of the Commonwealth) ‘Victoria’s sovereign, indigenous peoples.’ Modelling itself on the nineteenth-century leader William Barak, who adopted the roles of artist, political activist, leader, diplomat and translator, Sovereignty consciously steps outside the traditional territory of contemporary art—but in what sense?

A central aspect of Sovereignty, discussed in the exhibition catalogue, is the political struggle for First Nations people to be recognised as sovereign through, for example, a treaty (a theme depicted in Marlene Gilson’s Land Lost, Land Stolen, Treaty (2016) showing the signing of John Batman’s nullified 1835 treaty with the Wurundjeri). It is in the context of political, cultural and legal dispossession, as well as over 200 years of colonial occupation, that Sovereignty seeks to form and assert at ACCA a genuine space of First Nations sovereignty.

In contrast to this territorialisation of ACCA, contemporary art tends to ally itself with the de-territorialised and transnational spaces that have become widespread since the late 1980s and early 1990s. This cosmopolitan aspect of contemporary art has been framed as a part of its progressive leftist agenda, where the essentialist territories of modernism were replaced by fluid, dialogical categories of the contemporary—a kind of artistic United Nations. Admittedly, this has also meant the regimes for contemporary art were exposed to the accusation of right complicity: if the neo-liberal system of global capital flows is managed by a political and financial elite, so the flows of contemporary art have been said to be managed by an international curatorial class. Like the British Empire, the international contemporary art world is a transnational space on which the sun never sets.

Still, alongside its broad selection of cultural products Sovereignty does include straightforwardly contemporary art. For example, Megan Cope’s Resistance (2013), a series of right-wing protest placards made of corflute lie flaccidly in a discarded heap in the corner of the final room. As well, Brook Andrew’s The weight of history, the mark of time (sphere) (2015), a commission by Destiny Deacon and Virginia Fraser, and a work by Yhonnie Scarce also present contemporary art formats, utilising mixed-media installation and dispersed production methods.

However, since Sovereignty is premised largely on geographical criteria (South East Australia), most of its artists cannot be a part of the international contemporary art scene. In any case, the political project that Sovereignty aligns itself with may not find a helpful ally in the transnational contemporary art world. As many know, the more successful you are as an artist, the less likely you are to live in your native country (and unlike the figure in Maree Clarkes Born of the Land (2014), you’re even less likely to be on Country)—you’re in Berlin, New York, L.A., London, etc. This element of contemporary art may suit artists whose nations successfully de-colonised after the Second World War. However, Australia’s Indigenous nations never experienced de-colonisation in the way many other colonised nations did in the 1960s and 1970s. They still fight for land, power and identity; a struggle that is ongoing today, as documented in Sovereignty through the photographic practice of Lisa Bellear.

From this perspective, contemporary art is doubly problematic: How do you assert your nationalism under post-national conditions, fight for land rights in a deterritorialised world, and assert your identity under the fluid regime of contemporaneity, be it characterised as left cosmopolitanism or right neo-liberalism? An absentee from Sovereignty, Brisbane-based artist Richard Bell is perhaps one of the few artists to successfully do this in the international contemporary art world, having pitched his Tent Embassy (2013–ongoing), a recreation of the Aboriginal Tent Embassy, at museums and international biennales from Melbourne to Moscow, Brisbane to the Netherlands.

Instead, Sovereignty tries to assert Indigenous sovereignty directly, outside contemporary art’s globalist forums. Resistance through cultural continuation and revival, for example, is a theme carried through the work of a number of women artists in Sovereignty. As Indigenous writer Tony Birch writes, cultural revival can be a way of speaking “truth to power.” This is seen in Vicki Couzen’s possum skins, Bronwyn Razem’s woven traps, Maree Clarke’s necklaces, Glenda Nicholls’ cloaks and Lucy Williams-Connelly’s hot-poker drawings. In these works, mourning lost knowledge is mixed with the empowerment of cultural reclamation in which sovereign women carve out their own cultural space. Kent Morris’ digitally altered photographs similarly transform urban environments into sites of cultural sovereignty. And Jim Berg’s Silent Witness (2005), a wallpaper depicting scarified trees (and as paper, also made of trees), gives affect to the territorial claim of First Nations sovereignty at ACCA.

And it is this facet that might just explain why Sovereignty doesn’t feel like an exhibition of contemporary art: because it declaims against contemporary art’s cosmopolitan, de-territorialised and transnational world-view.

Sovereignty, the inaugural exhibition in the program at ACCA developed by new director Max Delany, also tells us something about the direction the gallery may take. Previous director Juliana Engberg was well known for putting on shows of international contemporary artists, thereby positioning herself as a member of that international curatorial class who manage the global flow of art (and opening herself up to the accusation of foreign adventurism at the expense of local, especially Indigenous, artists). Delany, on the other hand, has already suggested a different approach with Sovereignty. This is evident in his curatorial model, where, through a collaborative and consultative process, he hands institutional power back over to the local territorial sovereigns sharing curatorial agency with Wemba-Wemba and Gunditjmara artist, writer and curator, Paola Balla.

By distinguishing himself from the previous internationalist director (at a time when world powers are suddenly re-asserting sovereignty and territorialism), in a strange way Delany seems to present himself in a similar manner that Trump presented himself to the American people: as the apparent alternative to an entire international political class, be it in its left (cosmopolitan) or right (neo-liberal) versions. Like all forms of territorialism, however, this model remains necessarily exclusive, which is evident in the conscious choice to exclude non-South East Australian peoples and, as a Palawa friend pointed out to me, the apparently unconscious exclusion of Tasmanian peoples.

Against contemporary art’s de-territorialism, the re-territorialisation of the space at ACCA is further exemplified through the theme of war. This is seen in Steaphan Paton’s videos Cloaked Combat #2 & #3 (2013), Reko Rennie’s ironically high-vis camouflage banner work Always here (2016), or in Peter Waples-Crowe’s more discrete works on paper, such as Soldiers (2015). On the day I visited the exhibition (January 26), a series of banners had been lifted from the wall by the political group WAR (like weapons from ACCA’s armoury) and carried onto Melbourne’s streets in protest. Launched in November 2014 at the G20 protests, WAR models itself on various sovereign and Black nationalist movements, placing itself in the legacy of Brisbane’s Musgrave Park, and figures like Gary Foley, Malcolm X, the Black Panthers, and the pan-African nationalist, Marcus Garvey.

Before the concept of sovereignty became a defining element of territorial jurisdiction (a surprisingly recent innovation), generally colonialist and Indigenous people understood their conflicts as war. Conflicts were resolved through shared notions like reciprocity and retaliation. Around 1830, the British sovereign claimed to end this war by calling Indigenous people into its jurisdiction, using the tools of criminal law to control or remove Indigenous peoples from their lands. Gilson’s painting Tunnerminnerwait and Maulboyheenner (2015) shows how this soon led to public, legally sanctioned executions of First Nations peoples. A state of war is one in which sovereign powers face-off. If sovereignty was never ceded, then the sovereign has to maintain, as the Warriors of the Aboriginal Resistance do in their founding Manifesto, that “this war never ended.”

Paris Lettau is an arts writer from Melbourne.