The Score

Kate Warren

One of the things I enjoy most about going to an orchestral performance are the moments when the musicians onstage complete their final warm-ups, exercises and tunings. Being not yet focused into a single force, the performers’ last-minute preparations are individual and not precisely coordinated or harmonised. Nonetheless, they blend and complement each other, creating a mix of the individual and the ensemble. Walking into The Score at the Ian Potter Museum of Art gave me a similar impression. Strains of melodies, sounds and various aural devices confront the visitor as soon as they enter, and while it’s immediately clear that these sonic strains emanate from distinct artworks and spaces, in their overlapping and entangling they create an impressive exhibition that is more than the sum of its parts.

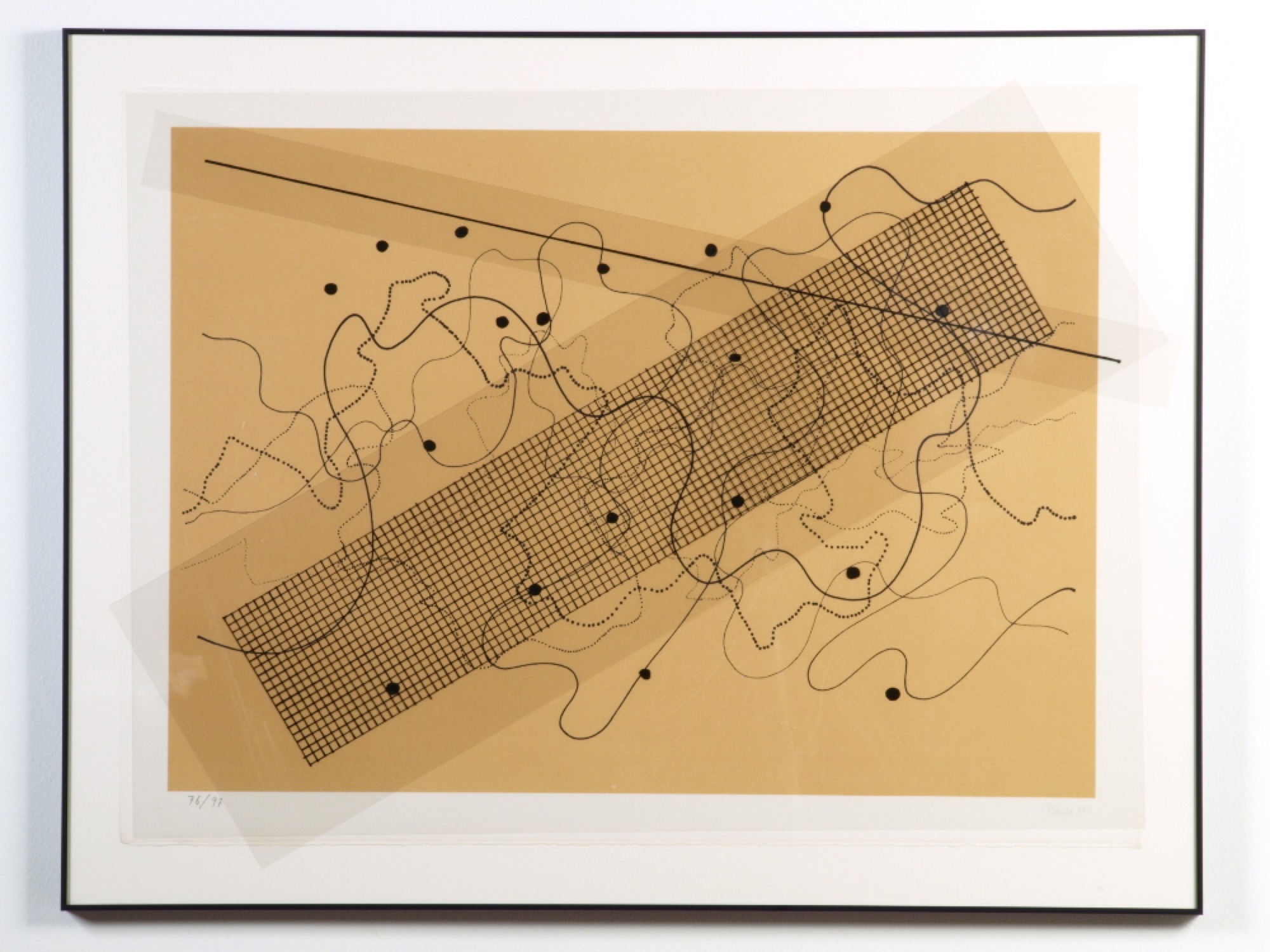

Stretching across all three levels of the Potter, The Score is an ambitious exhibition that encompasses much more than artists working with music or sound. Through the motif of the “score” it explores themes of translation, performance, visualisation and cross-pollination between art forms. As a university art museum, with access to academic and archival collections, as well as an established commitment to Australian contemporary art, the Potter is ideally placed to present an exhibition like The Score. Curator Jacqueline Doughty has thoughtfully made use of all these resources available. Inspired by a graphic notation score by composer Cornelius Cardew, the exhibition includes a number of archival documents and recordings by Cardew and other modernist composers (including Karlheinz Stockhausen, George Crumb and Lyell Cresswell, among others), drawing its materials from multiple collections, including the Grainger Museum and the Baillieu Library’s Rare Music Collection.

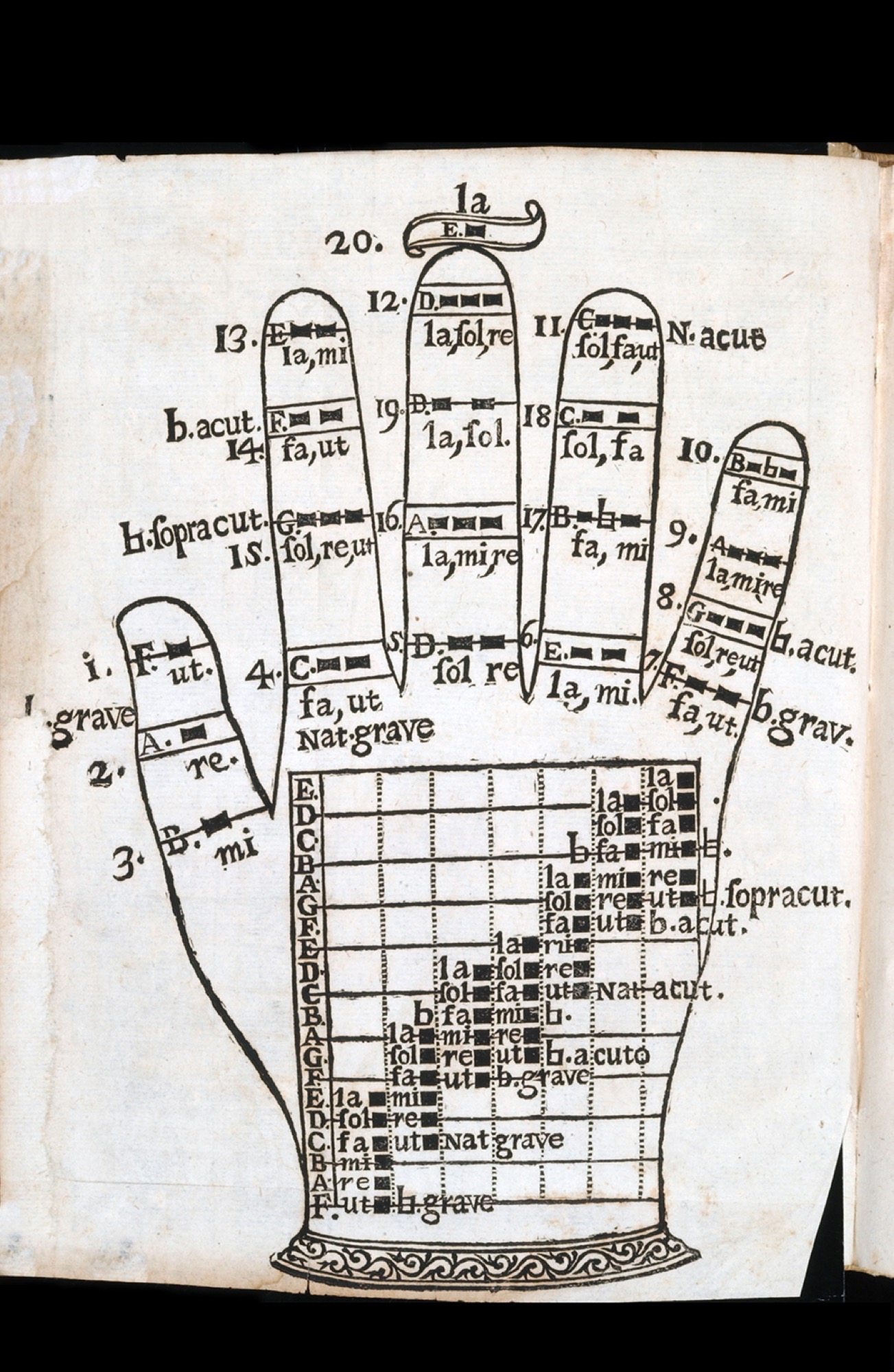

Graphic scores break from traditional Western notation conventions, which usually comprise of a five-line stave, clef, key signature and time signature, followed by various notes, rests and other musical characters. Graphic notations use more varied, expressive and less standardised signs—including colour, shape and size—to construct the compositions and communicate to the eventual performers. In taking this unusual schema as the exhibition’s genesis, The Score laid the groundwork for its central interest in translation, transposition and cross-art form relations. Basing an exhibition around such an inconspicuous motif–music is heard, but scores themselves are in fact rarely seen–there is a risk of fetishizing the visuality of musical scores as discrete objects. On the whole the exhibition avoids this; although in doing so it did have the strange, almost counter-intuitive effect of lessening the impact of some usually critically compelling pieces, such as those by Marco Fusinato and Mark Applebaum, whose focus was more precisely on musical scores as visual objects. As packed full of works as The Score is, it could not accommodate some of these artists’ more expansive pieces.

To my eyes and ears, the most successful pieces were those that understood and activated the score as a generative potential, to experimentally create something new through translation and transposition–be they sonic, visual or physical creations. Sometimes, these translations were quite literal, as in Nathan Gray’s contribution Treatise: Pages 131 and 78 (2012), in which Gray transformed two pages of Cardew’s graphic nation score Treatise into a three-dimensional installation of wood, aluminium, rope and tape. The sculptural elements of Gray’s piece were movable and, most importantly, playable. Extending Gray’s previous works such as Species of Spaces (2013–14), which explore the aural potencies of everyday spaces and objects, Treatise continues the possibilities within Cardew’s score for open, performative interpretation.

Mia Salsjö’s multi-faceted project reveals the processes and final outcomes of the artist’s acts of self-reflexive translation and scoring. Salsjö assigns notes to letters of the alphabet, and translates into music certain words that she feels correspond to her practice. She plots and expands these repetitive fragments into complex drawings (a number of which were on display), which also respond to architectural and spatial structures. Her work Modes of Translation (2016–17) was influenced by one particular site–the buildings of the National Schools complex in Havana, Cuba–and the final two-channel video featured nine violin students performing Salsjö’s composition under one of the school’s crumbling domes.

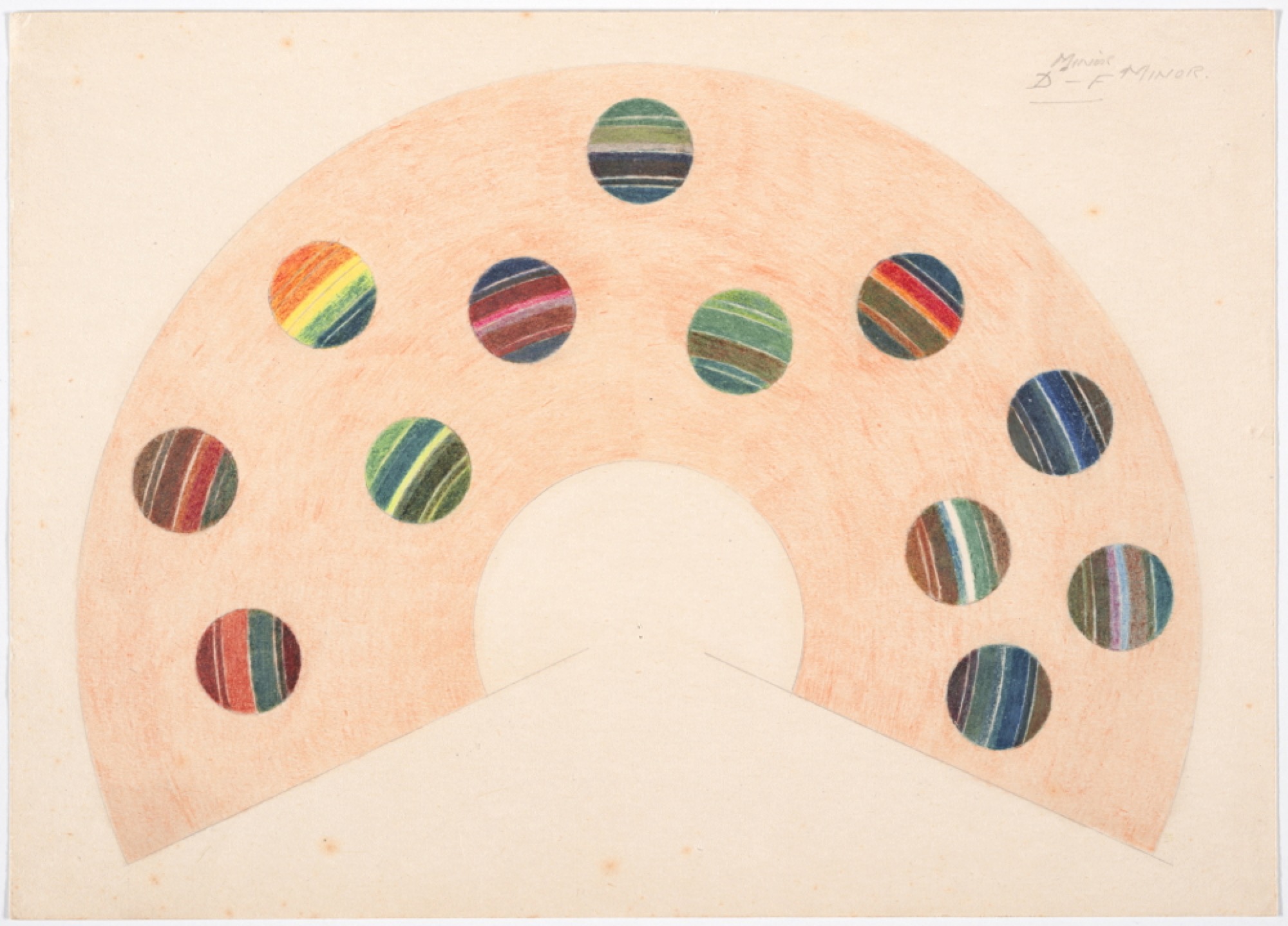

Both Gray and Salsjö are Australian artists, reflecting one of The Score’s key strengths: its clear focus on local artists and histories. Thus the inclusion of an important figure of European modernism, Ludwig Hirschfeld-Mack, is framed around the artist’s later involvement as a teacher at Geelong College in the 1940s and 1950s. The exhibition includes a number of stringed box constructions called Colour Chords, which Hirschfeld-Mack created during his time in Geelong. By exhibiting Hirschfeld-Mack’s instruments and watercolours alongside the earlier crayon and pencil compositions of Australian Modernist artist Roy de Maistre, the exhibition hints at the geographically and culturally complex interplays between and within twentieth-century modernisms. This sense of dispersed origins is also evident through Agatha Gothe-Snape’s contemporary piece Inexhaustible Present (2013), which contained a fitting tribute to pioneering New Zealand artist and filmmaker Len Lye. From the 1930s onwards Lye created his ground-breaking direct animation films by referring to optical soundtracks, with the shapes of the phrases inspiring his scratchings and stencilling on celluloid.

The influence of other forebears such as John Cage and Steve Reich cast long shadows in The Score, but it is the local and younger international artists who stand out. With such a rich thematic basis, it would surely have been tempting to include works by international art stars like Anri Sala or Christian Marclay, who have become well-known for working with such themes. And as impressive as their works often are, the exhibition is stronger for their absence. Thus instead of seeing Marclay’s Mixed Reviews (American Sign Language) (1999), we instead have the delightful video Classified Digits (2016) by Christine Sun Kim and Thomas Mader. Despite being born deaf Sun Kim works primarily with sound, creating scores that combine standard notation and gestures from American Sign Language. Classified Digits presents a take on the improv game “Helping Hands”, acting out various awkward contemporary social encounters (such as “One person avoiding another person they know”) through Mader’s fingers and Sun Kim’s expressive face.

The intersection between physical gestures, language and storytelling found in Classified Digits is a resonant motif that weaves its way through much of the exhibition. It informs video installations by Angelica Mesiti, Sriwhana Spong and, most compellingly, Yuki Kihara’s Siva in Motion (2012), in which the artist used stop-motion after-effects to animate her performance of the Samoan narrative dance taualunga. Kihara’s movements narrate the experiences and stories from a deadly tsunami in 2009 that caused death and destruction in Samoa, Tonga and surrounding nations. Numerous artworks in The Score powerfully demonstrate how the complex relations between music, gesture, language and narrative are not only artistic concerns, but are always situated and embedded socially and politically. Particularly striking are Manyjilyjarra artist Kurltjunyintja Jackie Giles’s painting Tjamu Tjamu (2005), which translates his traditions of oral storytelling and dance into visual form and Charles Gaines’s Sound Text (2015), where the artist transforms found songs with new lyrics and harmonies derived from political texts, in this case by nineteenth-century abolitionist Frederick Douglass. These multi-faceted motifs between and within artworks may not always harmonise, but they can work both with and against each other to create a larger ensemble of resonances.

Kate Warren is a writer, curator and researcher based in Melbourne, with a particular interest in cross-overs between contemporary art, film, photography and moving image practices. She received her PhD in Art History from Monash University in 2016.