The Nicholas Building “Up Late”

Helen Hughes

Those who prefer their art galleries stacked one on top of each other—as opposed to sprawled out, Sexpo style, at the Convention Centre—would do well to visit the Nicholas Building, where several art spaces opened their doors to punters on Wednesday night as part of Melbourne Art Fair’s “Up Late” program. Queuing for the lift in the Cathedral Arcade, I was quick to encounter Dario—a charismatic member of the Nicholas Building Association—who advised that the best way to “do the building” was to take the lift up to the ninth floor and wend your way down. Part of the lifeblood of the building, he was mysteriously omnipresent all evening—coursing through lifts, stairwells, hallways; putting up posters, snapping pics, gabbing with tenants.

The building is a genuinely social place and the community it houses is real. Here, the production and presentation of art occurs in tandem. Thus, we encounter, on the ninth floor, an open studio packed with artists working across a range of media—from oil painting to ink cartoons to digital illustration. Among them: Emma Carter, who has kept a studio in the building for some twenty-seven years, and who presented a suite of otherworldly landscape paintings informed by the way animals perceive colour. Neighbouring artist Kate Wallace exhibited enigmatic, small-scale oil paintings lined up like delicate tiles—each a subtle abstraction of photographic details subject to the fog of memory.

Downstairs on level eight, Caves hosted an exhibition curated by Rozalind Drummond, titled Communal Atmosphere or The Space The Air (Falls) behind you as you move. Fifteen artists—including blue chippers like Kerrie Poliness and Stephen Bram, alongside old faithfuls like Yanni Florence—presented work at intimate scales, en masse filling the small gallery with a buzzing, hive-like quality. (Or was the actual dripping honeycomb of Playground Love, 2022 by local beekeeper Honeyfingers?) Ruth Cummins showed The View (2022)—a charming, lap-sized patchwork quilt made from her old Brunetti’s apron along with other sentimental fabrics, which she hung from an olive branch gleaned from her parents’ grove. A moving-image work by dancer Shelley Lasica was hung next to a lush staged photograph by Drummond, which featured Lasica’s son (Moss) as a model. At Stephen McLaughlan Gallery (also a Nicholas Building stalwart, McLaughlan having kept a space there for almost thirty years), Deborah Klein’s haunting paintings of the backs of women’s heads were a standout.

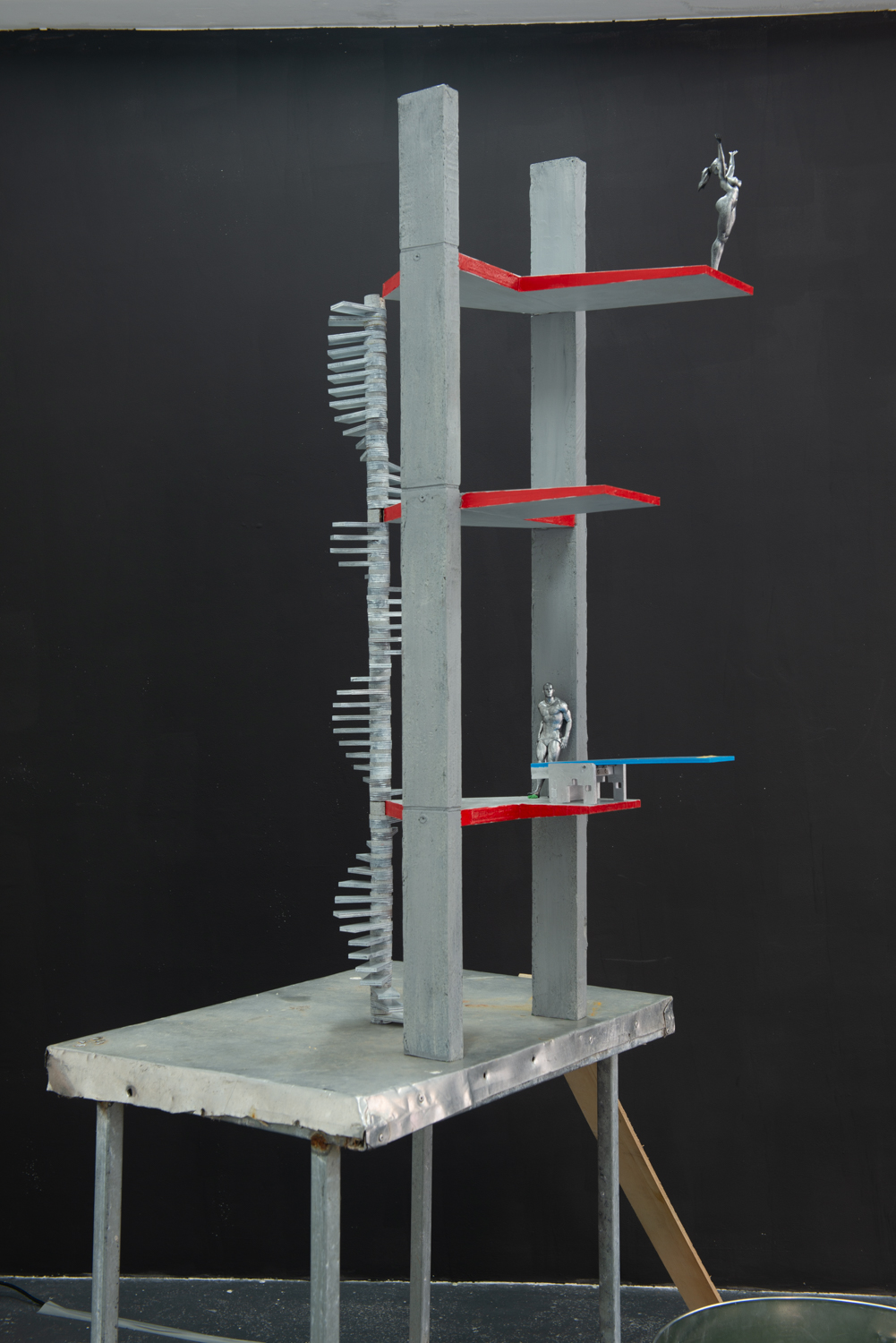

Blindside—on level seven—presented a group exhibition curated by Sanja Pahoki and Nikos Pantazopoulos, lecturers at VCA and RMIT respectively. Featuring work by covid-era art-school graduates, the show evidenced intergenerational mentoring in and beyond the university—a “communal atmosphere” at home in the Nicholas Building. Christopher Theofanous’s dense painterly compositions—of shimmering colour palettes replete with fine black outlines—shone like stained-glass windows or brilliant-cut gems as they did at the 2021 VCA grad show. Matthew Ware presented a kind of evil, small-scale model of the brutalist diving board at the Harold Holt public swimming pool in Glen Iris. Kind of evil because the diving board doubled as an elaborate trap that would send mice to their watery graves—an irony that wouldn’t have been lost on the former Australian prime minister for whom the suburban swimming complex was named.

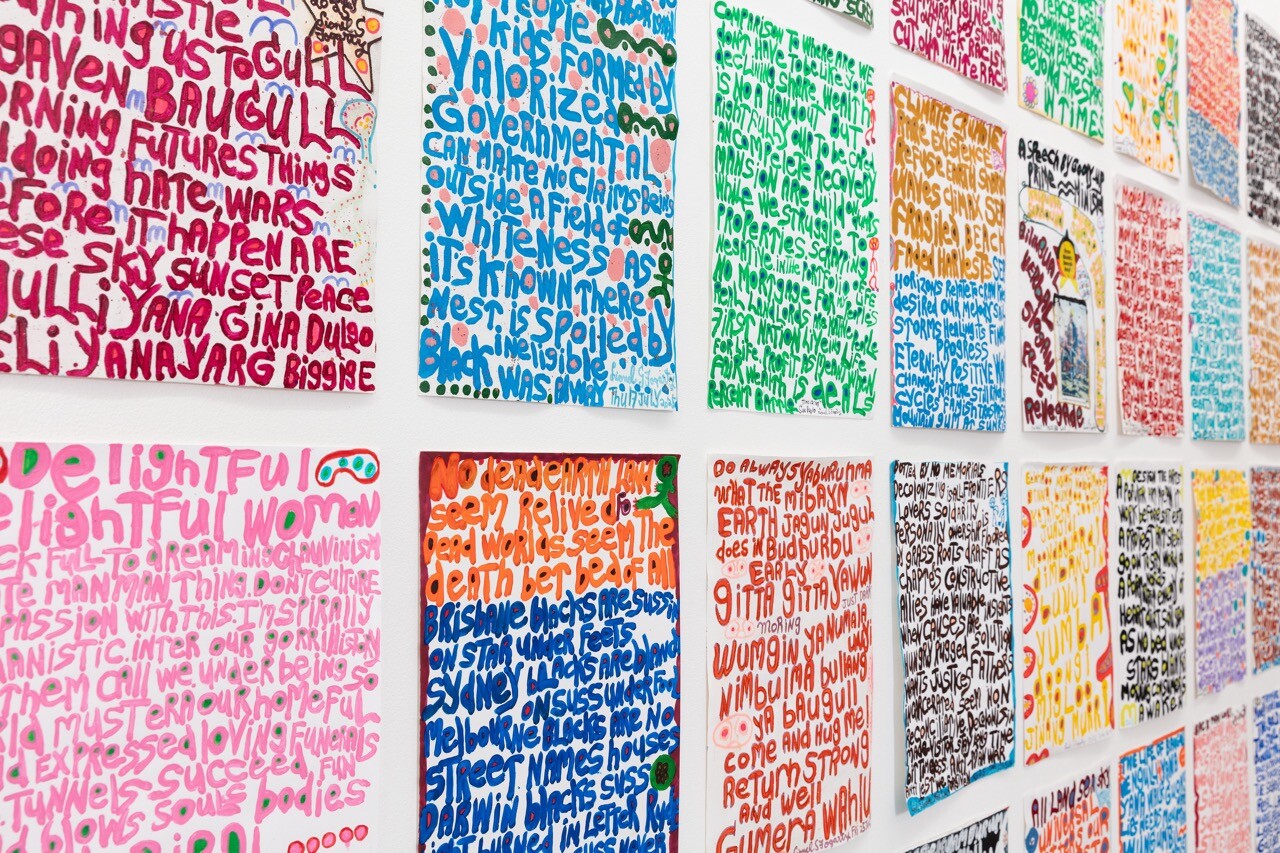

Down the corridor, 99%—the week-old brainchild of curator and critic Chelsea Hopper—presented a lecture by Zoë De Luca, the resident art historian on Richard Bell’s Embassy project during the Venice Biennale in 2019, which this year travels to ruangrupa’s documenta as the next stop on its illustrious artworld itinerary. Framed by Bell’s artworks in the gallery’s inaugural exhibition RICH, De Luca worked up a powerful analysis of the ‘collateral’ exhibition event. In so doing, she brought into contact a range of architectural, spatial, and ideological oppositions: Bell’s …no tin shack…(2019) and the Australian Pavilion; Bell’s Embassy outside/alongside the Venice Biennale proper; the Aboriginal Tent Embassy with Old Parliament House; Courbet’s personal Pavilion of Realism with the 1855 Exposition Universelle in Paris; the Vendôme Column and the Shrine of Remembrance; and, not least, the Nicholas “Up Late” program (of which her talk was part) alongside the Melbourne Art Fair proper. Titled ‘Which Side Are You On?’ De Luca’s performative lecture implicated listeners in a vivid picket line between these opposing though mutually constitutive forces, animating the room full of Bell artworks that, in turn, borrowed from the idiom of protest placards. “YES YOU CAN”, affirms one large yellow canvas in bold white letters; “DON’T EAT CAKE. EAT THE RICH.” announces the large red painting directly opposite.

Down on level three, the elusive Joseph Beuys Café—located at the dead-end of a corridor and only ever open by appointment—was bustling. Crowds milled at its entrance, clustered round its vitrines and bookshelves, and generally delighted in discovering this most surprising jewel in the Nicholas Building crown. Joseph Beuys Café is ostensibly an appreciation society for the great postwar German artist, self-styled “shaman”, pedagogue, environmentalist, and politician run by Australian collector and Beuys enthusiast, Ian George. Here was installed a selection of Beuys artworks and artefacts interspersed with video footage of the artist flickering across the gallery’s rough, paint-peeling walls. George was kept busy giving visitors his version of the “essential Beuys”—an analysis of the artist’s Sulphur-Covered Zinc Box (Plugged Corner) of 1970, comprising two vertically oriented rectangular metal boxes made to stand side by side with about an inch’s distance between them. Stay tuned for a multi-floor collab slated for later this year, where Joseph Beuys Café and 99% will co-present an exhibition focusing on Beuys’s grassroots organising.

But before signing off, it would be remiss not to acknowledge the existential threat facing the Nicholas Building: it’s still on the market where it is prey to Melbourne’s rapacious property development class. A vast support network quickly mobilised in defence of this “vertical village”, but the struggle to save the Nicholas Building continues. So, dear reader, if you have a cool million or seventy at your disposal, I heartily encourage you to contact the Nicholas Building Association and get behind the cause. In this respect, Hopper’s gallery, named for “the people” as against the concept of the elite 1% (per the late David Graeber’s formulation), is a timely addition to the building’s community at this critical moment in its history. It didn’t take too many plastic cups of Prosecco to convince me of which side I am on. Long live the Nicholas Building!

Helen Hughes is a Lecturer in Art History, Theory and Curatorial Practice in the Faculty of Art, Design & Architecture at Monash University.