The National 4

Anastasia Murney

I teach a course on contemporary art and one of the earliest conversations we have together is about what it means to be contemporary. Often, students will argue for a logical, common-sense answer: contemporary art is all art that is produced now. Well, it is, and it isn’t. The problem with this insistence on “nowness”is that it permits a generic inclusiveness that glosses over the difficult histories and antagonisms that continue to structure the present. What if there is something specific about this historical moment that distinguishes it from all other times? Perhaps there is a wider appreciation for the slipperiness of nations, which are not reducible to a spot on the map, a passport, or a common language. Nations are cultural artefacts of a particular kind, or so says Benedict Anderson. And nation-states are acts of spatio-temporal manipulation that naturalise themselves as common law and logic. I think of them as forms of science fiction, appealing to scientific rigour to legitimate their own truth claims.

So, The National: Australian Art Now is a trick question, one that invites us to dispel two fallacies: the impossible nowness of the contemporary and the fictive coherence of the nation (as if demarcating the nation of so-called Australia can be anything other than a colonial exercise). The exhibition doesn’t really try to achieve either of these things. The inaugural 2017 curators were clear about this, snuffing out a conservative impulse: “the intention … is not to attempt to encapsulate, delineate or define contemporary art in Australia.” So, in this vein, the 2023 iteration of The National is permeable and unfixed in a manner that feels appropriate. Nonetheless, the declarative statement of presence insists on certain stakes. What should an exhibition like The National do? How can we untangle the specific complexities of time and place, in dialogue with urgent social, political, and economic factors, inflecting what it means to be alive today?

Contrary to pronouncements that the 2021 iteration of The National would be the last one, the biennial survey exhibition is back and bigger. The fourth iteration is presented at four venues: the Art Gallery of New South Wales (curated by Beatrice Galton), the Museum of Contemporary Art (Jane Devery), Carriageworks (Freya Carmichael and Aarna Fitzgerald Hanley), and new partner, Campbelltown Arts Centre (Emily Rolfe). The exhibition eschews a unifying theme, but “collaboration” and “intergenerational knowledge” are cited as recurrent commitments. This is reflected in the overall figure of eighty participating artists, accounting for collectives, such as Jilmara Art and Craft Association, a remote Indigenous arts centre representing the Milikapati community of the Tiwi Islands. There is also Isabel and Alfredo Aquilizan, who create mixed-media installations from salvaged materials in collaboration with their five children, referring to themselves as the Fruitjuice Factori Studio. However, the total forty-eight exhibits are comparable to previous years (thirty nine in 2021, fifty eight in 2019), which makes the offerings at each venue feel somewhat contained. Overall, there are a number of delicate, introspective works in The National that meditate on aesthetic inquiries, citing vague and poetic references to nature, the everyday, or the human condition. But the exhibition is strongest when artists take the weight of the nation seriously and move to dislodge it.

In terms of Sydney’s art calendar, The National alternates with the Biennale of Sydney. In other words, the city is appointed to represent Australia to the world and Australia to itself. This flexing inward and outward—the articulating of the nation within a global framework and the global refracted through the lens of the nation—functions as a continual revision of histories and origins. Two prominent works in The National summarise this oscillation. Both entrances to AGNSW and the MCA are filled with large monochrome photographs. At AGNSW, Brenda L. Croft’s Naabami (Thou Shall/Will See): Barangaroo (Army of Me) (2019–22) is a photographic series of portraits of First Nations women and girls in Kaldor Hall, their lined and youthful faces lining the external walls of the Grand Courts. Together, the women radiate an arresting, defiant gaze, animating the warrior spirit of the Cammeraygal fisherwoman Barangaroo. It is this gaze that works to undo colonial naming practices that pluck and abstract Indigenous names, turning them into a veneer for casinos or tourist hubs. At the MCA, Hoda Afshar opts for a more fragmented sense of defiance, depicting a global zeitgeist drawing on various social movements and catastrophes. The photographs prefacing the exhibition are dotted with raised fists and faces, some tear streaked, some obscured. There is an inevitable glimpse back at the bushfires, the absence of colour transforms these scenes into light and ash. Afshar also presents a short video work of destruction in reverse: a rocket zooming back into its launcher, an exploded building re-assembling itself. This impresses a sense of the ceaseless production of images and fractured attention spans, flitting from one crisis to the next.

In one of the essays commissioned for The National, author and poet Ellen van Neerven reflects: “how to be tender in a Nation State, or tender in a State of Nation. With a sisterhood, a patten of support. Small gestures. Repetition, reinforcement. A chorus of Aunties.” This “chorus” immediately calls Croft’s work to mind. These strong matriarchal lineages trickle downstairs into AGNSW with Robert Fielding’s Milpatjunanyi (2022), a multi-channel video work. In a narrow room, a grid of video projections reveals a sequence of Anangu women engaging in a ritualistic storytelling practice originating on Yankunytjatjara Country. We do not see their faces, only their hands wielding a piece of wire to mark the earth, ribbing the red sand, creating sharp indents or soft, flowing lines. As the voices of the women overlap and bleed into each other, the forming and reforming of patterns is mesmerising. The wires themselves are like conductors, channelling a potent electric charge from body to earth and back again. Each one, with subtle curves and signature loops, is spot lit and installed on the wall behind. According to Fielding, the women once used bone, but wire is more flexible; it is an element of colonial pastoral life that has been adopted into culture.

I thought about Fielding’s work again at Carriageworks, looking at Katie West’s The women plucked the star pickets from the ground and turned them into wana (digging sticks) (2023), comprising three steel pickets strapped with old radios. If you listen closely, the radios emit a layered soundscape, mixing the multi-species rhythms of West’s family farm in Western Australia with the monotonous hum of distortion. Like the Anangu women, she takes these tools of industrial agriculture—used to stake a claim, to demarcate boundaries, to hold livestock or crops—and recalibrates their relationship to land. While parts of the exhibition at Carriageworks feels a bit disjointed, the venue offers one of the most memorable rooms in The National, not because it features a selection of “spectacular”artworks but because there is a skilful balance between these large-scale works and the smaller ones. Alongside West’s steel pickets, Elizabeth Day’s colossal installation addresses the colonial imposition of prisons on the landscape; it is a colourful scrawl of undone garments arranged into the brickwork of Parramatta Gaol. On a similar scale, Erika Scott’s The Circadian Cul-de-Sac (2023) is a cyclonic, suburban archive of crap. A towering wooden hourglass sits in a shallow bath of water, choked with cables and hose pipes, as if propping up an insatiable appetite for material accumulation. And then there is Nicole Foreshew’s sophisticated and ethereal counterpoint: a translucent set of cords made from organic materials set with mica, snaking from floor to ceiling. Close to the floor, there is a companion image of a snarling dog in a dirty mirror, across from the prison industrial complex. It’s a sensitive handling of the space, navigating moments of eruption and quiet contemplation.

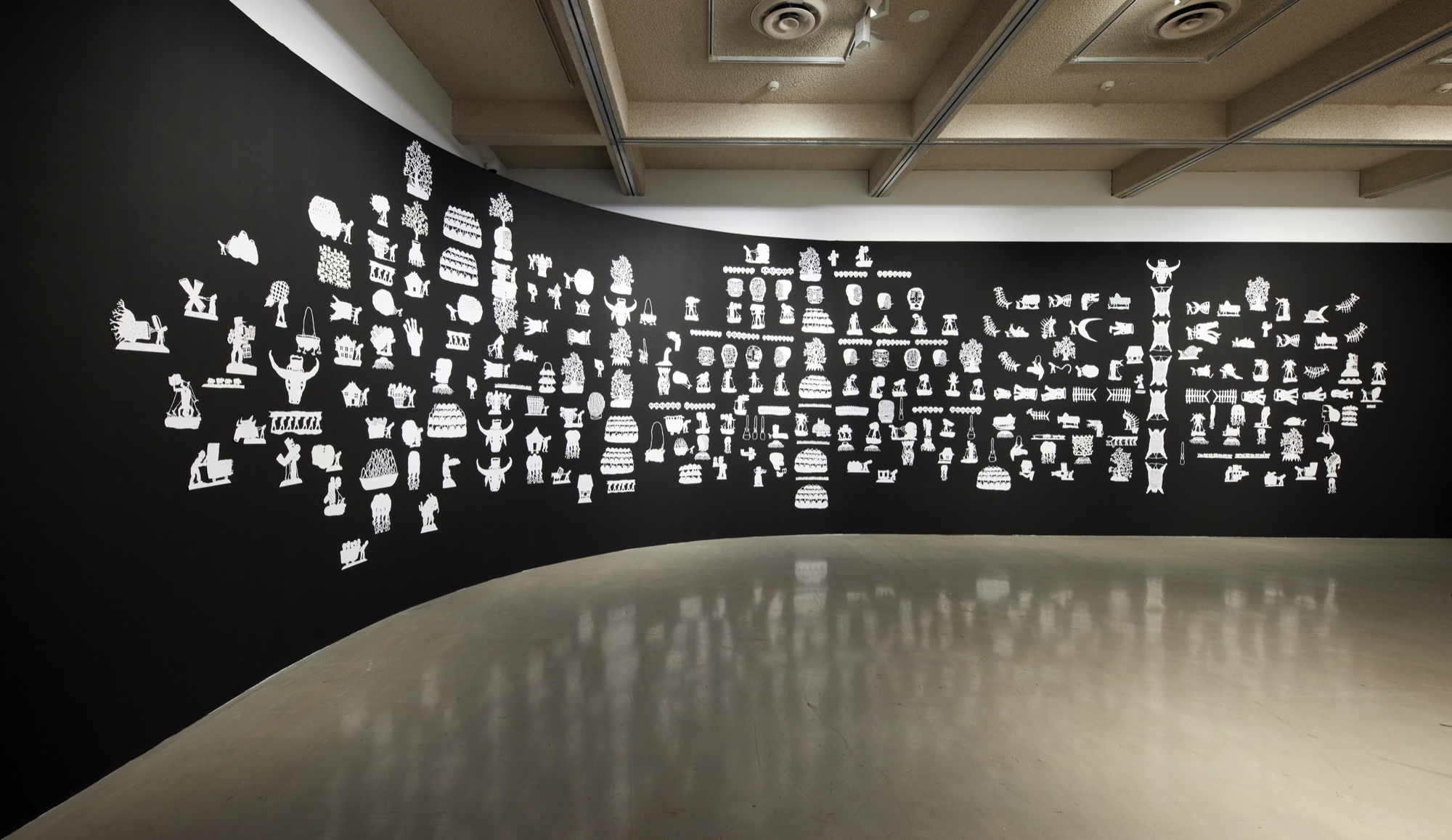

Campbelltown Arts Centre hosts some of the most striking art in The National. An obvious standout is Brook Andrew’s GABAN (2022), which translates as “strange” in Wiradjuri language. In this sixty-sixy-minute video, queer, trans, Blak and Brown actors seek to inhabit and unravel the institutional power of the museum. This is what Andrew describes as “post-traumatic theatre”, striving to crack open spaces for catharsis and healing. In the next room, Shivanjani Lal’s Aise Aise Hai (How We Remember) (2023) is a field of eighty-seven sugarcane stalks, cast with turmeric, limestone, and chalk and clustered together on bronze mirrored plates. The number references the boats that transported indentured Indian labourers to Australian-owned sugar plantations in the South Pacific, among them were Lal’s great-grandparents, in a process reminiscent of the Middle Passage. It is a monument—or perhaps a counter-monument—that testifies to the violence that is constitutive of nation building and the foundational racism of the settler state. The plantation logic is also detectable in Jumaadi’s paper cut outs, Joli Jolan (2022), which takes shape as a white pictorial language on a black wall, resembling inverted silhouettes. The work itself is a restless assemblage of humans, animals, ropes, shovels, and tree roots are distilled into succinct allegorical symbols. Often, the figures—humans and animals—are attempting to harness the raw strength of the natural world. A forest is not a forest but a stockpile of timber. A chicken is not a chicken but a resource to be consumed. Both Lal and Jumaadi gesture to the violence of abstraction that undergirds modern nation-states and their conscious entanglement with colonial capitalism.

As a venue, however, Campbelltown Arts Centre doesn’t quite cohere. The bright coloured walls throughout the exhibition disrupt the flow between spaces. There is a restaging of a small exhibition, Nih! Yeyi Yorga Waangkiny | Listen! Women Talking Now (Ilona McGuire, Yabini Kickett, and Sharyn Egan), which first opened at Freemantle Arts Centre in 2022. This is an interesting curatorial decision, but it feels too hidden and under-supported within the larger framework of the exhibition. Curator Emily Rolfe writes of The National: “the chaos is the shape of the project”. But the exhibition as a whole is not as tumultuous and energetic as one might expect. At the MCA and AGNSW, there is a handful of artists engaged in quiet, formalist, or whimsical inquiries, such as Diena Georgetti’s retro modernist paintings or David Sequeira’s meticulous arrangement of colourful, geometric circles superimposed over sheet music. The effect is a kind of rootlessness, a feeling these works could be placed almost anywhere. Again, in its fourth iteration, what should The National do? At times, the exhibition feels too clean and precise. What does it mean to be tender in a Nation State, or tender in a State of Nation? This is to contemplate the invisible histories and infrastructures of nation building and to invoke a complex constellation of suppressed voices and memories, like the whispering sounds of West’s radios or the matriarchal chorus of Aunties in the work of Croft and Fielding. The National is still going to be haunted by the powerful fiction and material violence of the settler-colonial nation(state), so why not embark on a more decisive unravelling?

Anastasia Murney is a writer and teacher living on Gadigal land. She holds a PhD from the University of New South Wales.