The Housing Question

David Wlazlo

In architecture, people love modernism. They just can’t get enough. Clean lines, large windows open to lush gardens, simple wooden furniture. People also hate modernism. They detest its pretensions of purity, cleanliness, and prescriptive universalism. I’m sure I could find many of you nodding in relief. So, who loves modernism, and who hates it? What class, type, mode, genre of people? What rights do these people have? What category of people are we talking about and what claims can I or anyone else make about this imaginary group of people?

These issues are at the core of The Housing Question (2019), a video work by Helen Grace and Narelle Jubelin, currently on show at Geelong Gallery. Sumptuously shot with inter-titles and an immersive soundtrack by audio artist Sherre DeLys, the work has been shown at quite a few institutions since 2019, often with additional curatorial embellishments. At Geelong Gallery, the work was shown in dual channel parallax: the same video, projected side by side with off-set starting time. Sitting in the simply-furnished and darkened room, there are visual and auditory slippages between the two channels until it becomes clear which channel has the audio (hint: it’s the one on the right).

Despite the first impression of an immersive video installation, the work has a strong structure once you pick up the thread of its beginning and end. Divided into four chapters by inter-titles and thematic focus, the work is a dense, thoughtful, and essayistic study of twentieth-century modernist public housing principles, shot through with a work/performance created on the glass of two major modernist private houses that now occupy the status of museums. Houses of ur-modernism. Sites of primal architectural scenes.

Each chapter of the work is given a title, much like a modernist architectural manifesto: “Discourse on the Oval,” “Discourse on the Radial,” “Discourse on the Square,” and “Discourse on the Fabricated.” The first, on the Oval, shows a walk through of José Antonio Corrales and Ramón Vázquez Molezún’s Casa Huarte (1966) in Madrid. A modernist design with all the features you’d expect: accentuated geometry, visible materials (in this case brick), restricted ornamentation, large windows everywhere. The house is clearly well thought out in terms of the site and aspect. The beautiful gardens are visible through the windows and in their reflection. Sliding doors are opened and shut, the sound of footsteps on the brick path can be heard, and—from the exterior—writing can be seen on the inside of the glass. The writing—and a voice-over—reads in Spanish from Engel’s 1872 treatise “The Housing Question.” The titular oval, it seems, is a modern oval table seen through a blurred window and in the background of another shot.

(sound by Sherre DeLys)

The Housing Question 2019 UHD video still

Courtesy of the artists

© Helen Grace and Narelle Jubelin

Inside the house, the chimney above the fireplace is austere and white. Projected onto this surface is a short film of a man dancing in the kitchen of a small housing-commission flat. His movements are short and restricted to cope with the space. As the dancer moves to open the cupboard door or the fridge, he conveys a kind of robotic surety: The movements as well as the space are void of any excess. The “Discourse on the Oval” ends with a series of shots through the maintenance and access tunnels of a large housing block with a voice over discussing refugee camps.

The “Discourse on the Radial” introduces the themes of social and public housing by a description—both audio and visual—of the foundation of Daceyville, a suburb of Sydney modelled on the “garden city” principle: open-space/park in the hub, streets radiating from the centre outward. Planned developments like this in the first half of the twentieth century hoped to provide healthy and open places to live for the working classes: they were designed for people in need of housing. The formal principle of the radial street is spliced in with images of Walter Gropius’s Dessau-Torten Estate in Dessau, built in response to Germany’s housing shortage in the 1920s, and the radial line—stretched out across the screen—of a contemporary refugee camp in Jordan.

Slowly, by montage, Grace and Jubelin are introducing problems that haunt the history of modernist architecture: housing for the workers, housing for refugees, and the continuing problems of displaced people globally. These social issues form a key concern for twentieth-century modernist architecture—especially the first half—along with material and form. The formal structure of the radial line speaks both to the challenge of thinking formally in the face of humanitarian crisis as well as its inverse: Are we going to talk in the abstract about the emergency housing of a refugee camp? Don’t we already? What’s the shape of the problem? Do people have a right to housing? What is our base-level response, and is it still to provide refuge?

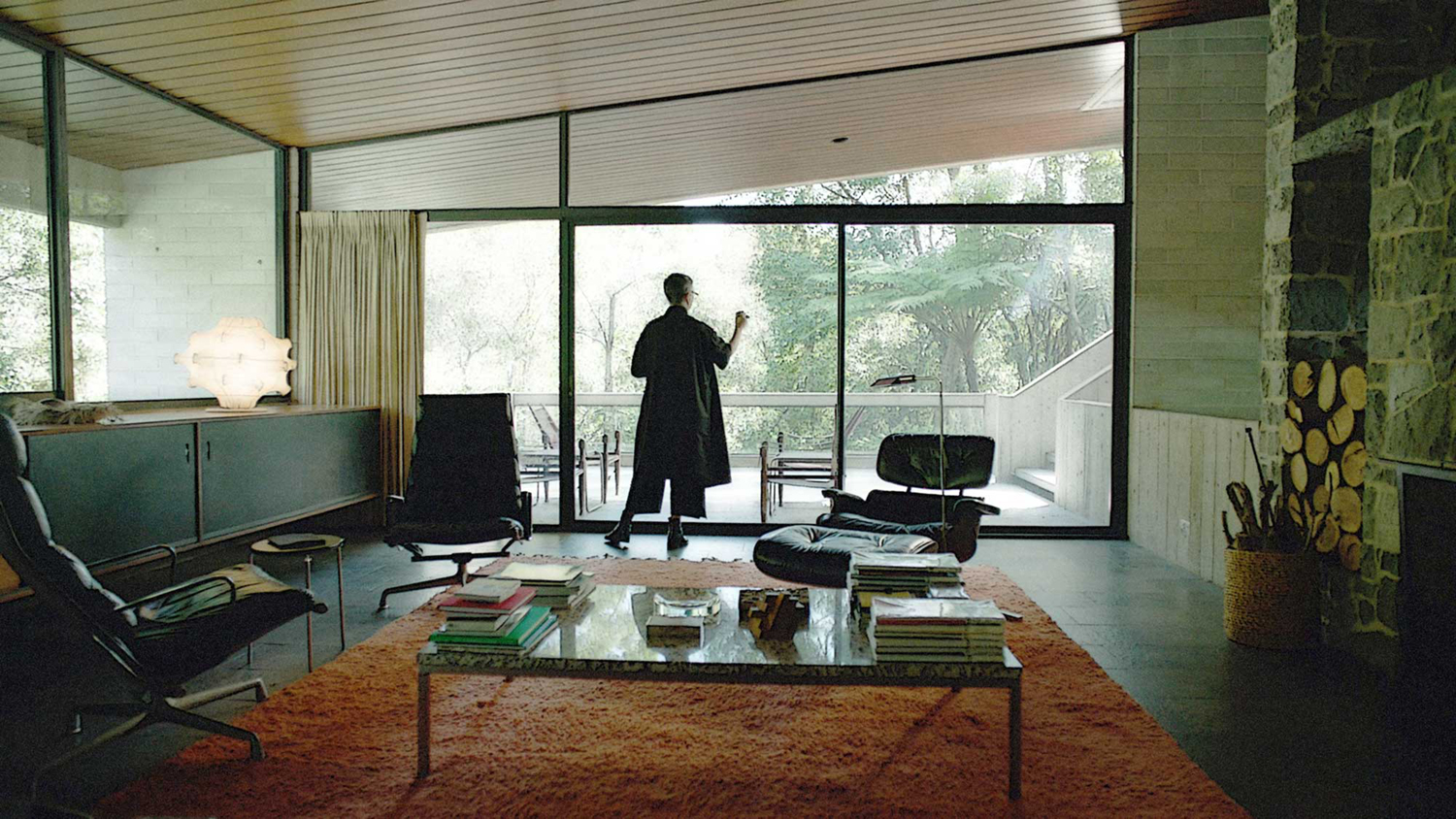

The “Discourse on the Square” continues the video, away from the refugee crisis and in the safe and reassuring we-love-modernism of Penelope and Harry Seidler’s Seidler House (1966-7) in Killara, Sydney. Both the camerawork and the house are beautiful. The same features of the Casa Huarte are found here: glass and light open to the garden, bold formalism, raw materials (concrete this time), excellent use of the site, as well as the added interior furnishings and artworks, particularly a work by Josef Albers (squares, of course), that the camera lingers over. The camera twists and turns a few times while showing fast edits of children running through the front door of this once family home. The artists write here, again, on the inside of the glass, more from the preface of Engels’ “The Housing Question,” this time in English. A voice over calmly reads the text.

(sound by Sherre DeLys)

The Housing Question 2019 UHD video still

Courtesy of the artists

© Helen Grace and Narelle Jubelin

I’ve only read the preface to Frederick Engel’s 1872 “The Housing Question.” I try to avoid the long-dead arguments in texts from this era (Proudhon vs Bakunin? Um, idk). Thankfully the artists also seem to be quoting from this shorter overview as well. The gist is that the industrial revolution in nineteenth-century Germany produced a housing crisis. Combined with the reduced income available through domestic and agricultural “side-hustles,” workers were poor and required easy mobility in order to follow suitable wages. When workers arrived in a new location, there weren’t enough houses. The “bourgeois and petty-bourgeois” solution, which was to try to get workers to own their own homes, suited Engels just fine: he thought it would lead to such economic ruin for workers that it would foment revolution faster. Owning your own house was for Engels “not only the worst hindrance to the worker, but the greatest misfortune for the whole working class” and “chains them to the spot and prevents them from looking around for other employment.”

This is the argument written on the glass of these typology-defining modernist private houses. Written from the inside, to be read from the inside, the artwork shows the performance of writing, perhaps didactically like on a whiteboard. The squeak of the pen merges with the native bird calls woven through the audio. Who is being educated here? Is the glass a metaphorical and discursive frame through which the inhabitants view the outside? Looking at the text on the glass through to the Josef Albers painting, I’m reminded of one of Geelong’s famous artists, Ian Burn, whose Value-Added Landscape series of 1993 also engages this triad of text, transparent medium (perspex in Burn’s case) and painting behind. I feel like this work is at home in Geelong. After moving through and around the house, the camera withdraws through the concrete eaves and up a light-well into the sky, the house becoming the only square roof in the leafy (upper-class?) suburb.

The fourth and final chapter of the work is “The Discourse on the Fabricated.” This portion of the video makes connections between images of the Second World War, Zillmere and Inala/Serviceton (suburbs in Brisbane that were developed as housing commission estates and for post-war migrants), and the Spanish public housing project La Coruña. There are also images and documents about Harry Seidler’s Rosebery Apartments (1967). An audioclip from historical protests is heard to say: “We don’t want stadiums, we want housing!” There’s a brief interview with an original resident of La Coruña, who—commenting on the austere undecorated appearance of the estate—remembers that the idea was that residents would come and personalise their homes. The bland white walls were intended to be a base for individual expression.

This idea of the modern architectural frame as a basic public provision is important. Throughout Grace and Jubelin’s work, inter-titles quote from an academic paper by writers Daniel Bertrand Monk and Andrew Herscher. In their 2015 paper “A New Universalism,” these writers lament that the refugee crisis in Iraq, combined with UNESCO heritage listing, have meant that historical—ancient—sites of refuge were turning away actual refugees in order to secure world heritage status and the tourism it brings. Monk and Herscher’s point is that the notion of refuge has become detached from the idea of the refugee, and that our collective responsibility toward refugees has changed accordingly. They argue that by focusing so specifically on the local (the individual building and site), buildings cease to represent shared human values and instead become instances of themselves in their own specific being. Architectural sites such as the ancient refuge/citadel of Erbil in Iraq become so unique under their UNESCO classification that they become incomparable, unparalleled members in a category that only they can be part of. For these authors this conundrum is a symptom of a more general condition where the focus on the local and specific is so strong that the ideas and ideals of the general humanitarian mission are lost or overlooked.

(sound by Sherre DeLys)

The Housing Question 2019 UHD video still

Courtesy of the artists

© Helen Grace and Narelle Jubelin

Considering The Housing Question, it’s clear that Grace and Jubelin are reflecting on modernism’s drive to think about groups, genres, types—especially when it comes to housing and architecture. The social ideals of twentienth-century modernism—public housing for workers, housing for displaced peoples—seem today to be diminished or dismissed as universalising, Eurocentric, patronising, or generalising. This leads to the question: What is our appetite for generalisation these days? We are all different and intersectional, this is true. But don’t we also participate and share in an ideal to be given the same equality or equity? What kind of people love or hate modernist architecture? What genre, type, class, or category? General people. Human people.

Of course, we all have different appetites for generalisation. It’s a slippery slope between saying that we all deserve equality/equity and saying that we’re all the same already. We’re all thrown into the world in which systems, values, injustices, and imbalances are already in effect. We’re not all the same and neither should we be. But is it a contradiction to say that we should all work toward treating each other as though we were, lifting up those in need as necessary? Monk and Herscher don’t offer a guiding answer to these questions, and neither do Grace and Jubelin. I can’t either. The contradiction between individual ontology (who we are) and generalised epistemology (how we are/how we can be) is just too great to hold in one argument on a page. Perhaps we can also ask, alongside your appetite for generalisation, how much contradiction can you drink?

(sound by Sherre DeLys)

The Housing Question 2019 UHD video still

Courtesy of the artists

© Helen Grace and Narelle Jubelin

Work like The Housing Question is sometimes hard to write about because it has such dense and intellectual content. It’s hard to assess without simply re-creating the arguments, references, and sources of the artists. For some, discursive and essayistic work such as this may seem exclusive and inaccessible, hard to engage with in depth. To be honest, any artwork that I have to log into JSTOR to chase up a reference is definitely in the camp of Homo Academicus. I’m in that camp too (I’m not pointing fingers here). The work’s form is beautiful and easy to immerse oneself in. The arguments and positions it presents are a little harder to access. Education, like housing and refuge, is another universal and general ideal derived from the values of human rights. But it’s important to remember that the ideals of modernism, global education, and human rights are very recent phenomena. JSTOR may want us to pay to read articles, and capitalism may want us to remain fixed to a specific intersectional consumer identity, but perhaps the more liberating position to take is to speak from the general, to reach out and claim the universal.

Who are the artists Helen Grace and Narelle Jubelin? What kind of artists? Human people. The Housing Question is an increasingly relevant meditation on the question of housing and how it affects other human people, particularly those in need. All across the world houses are being destroyed, people are being displaced, workers are moving, and the costs of simply living are increasing. Down the road on the Bellarine peninsula human people are faced with problems associated with housing. Some human people are being forced onto the streets and into their cars. Having a mortgage is hard and renting is harder. Having your land stolen and then turned into place-less architectural sites is harder still. Perhaps it is time again, like it was for Engels 150 years ago, to reorient ourselves toward the ideal of human collectivity. To re-think the group and its needs and formulate those needs into rights. The right to safety, the right to be heard and represented in politics, the right to not be colonised, the right to justice, and the right to housing.

David Wlazlo is an artist and writer currently living on Wathaurong country.