Installation view of Emily Hunt: The Grotto at Art Gallery of New South Wales, 22 June – 7 October 2024, photo © Art Gallery of New South Wales, Felicity Jenkins

The Grotto

Gabrielle Chantiri

I remember Sand Play for its witches. In a small corner of Knulp Gallery artist Emily Hunt had laid neat, curved paths of sand that led to hexagonal altars and dead ends. The tiny ceramic witches placed along the paths looked to be talking, praying, and giving salutations for the fine arrangement they were in. Berlin-based Australian artist Hunt’s most recent exhibition at the Art Gallery of New South Wales (AGNSW), The Grotto, maintains this preoccupation with miniature forms, yet, as the title suggests, these small symbols build a place, a grotto. She’s referencing the Domus Aurea, the palace of emperor Nero that was excavated in the late 1400s to reveal frescoes depicting whimsical plants, creatures, and figures. These fantastical inventions influenced the graphic and decorative arts of the Renaissance and beyond. The grotesque as it appears throughout art history is another of Hunt’s preoccupations in this show. The miniature, the grotesque—these are points on a map of The Grotto. Though never stated directly, The Grotto contains a myriad of references to the history of walking and mapping, through which we might read Hunt’s work.

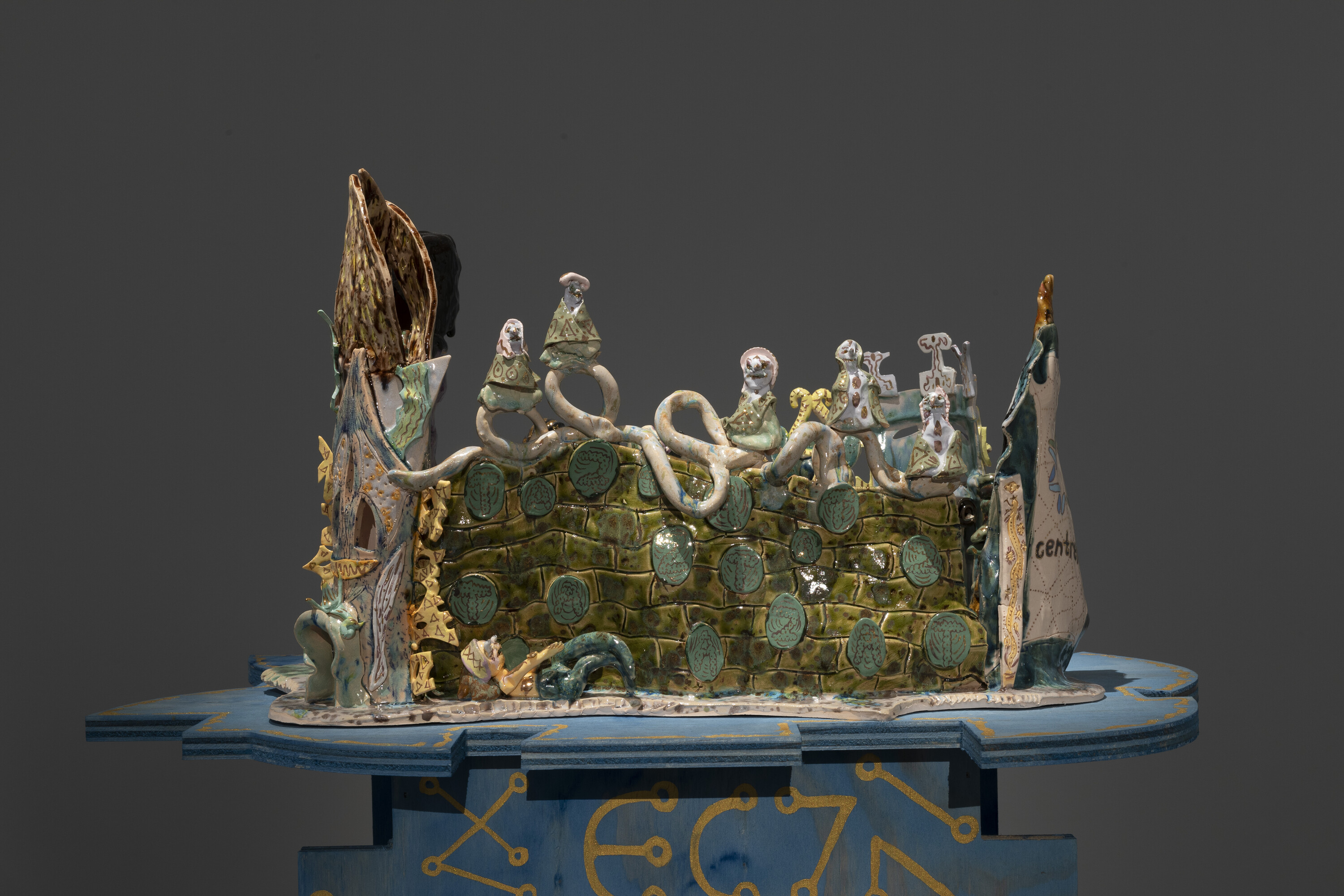

Emily Hunt, Psychedelic Centrelink, 2024. Glazed stoneware, gold lustre. Photo: Jessica Maurer

Emily Hunt, Psychedelic Centrelink, 2024. Glazed stoneware, gold lustre. Photo: Jessica Maurer

In Psychedelic Centrelink (2024), Hunt was inspired by the writings of anarchist American author and poet Peter Lamborn Wilson, who advocated for temporary occupations of private spaces called “temporary autonomous zones.” Made from glazed stoneware and gold lustre, the job centre is a citadel overrun by benevolent spirit guides. In her work Chain of being (2024), small etchings printed in black ink on paper depict locations in Sydney that, for the artist, are “psychically charged” and haunted by memories of the past, including Callan Park Hospital for the Insane (also the site of the Sydney College of the Arts from 1992 to 2019), the Star Amphitheatre at Balmoral Beach and the Sirius building at The Rocks. In The Sydney Egregore Walk (2023-24), a series of buildings and monuments in Sydney, such as the Grace Brothers department store at Broadway and Walter Burley Griffin’s incinerators at Pyrmont and Willoughby, are hand painted onto the walls of the exhibition. In the centre of the room, we see the inhabitants of this city—six marionettes modelled on Australian figures who are linked with the occult and spiritualism: the academic Nevoll Druru, artist Mikala Dwyer, artist Rosaleen Norton, and Hunt herself, to name a few. The Grotto opened with a series of performances by Hunt and her marionettes, recounting the stories of the lives upon which the puppets are based. The title of the work, Homunculus trance (2023-24), refers to the homunculus in medieval alchemical literature, a miniature figure brought to life by magic.

Performance stills of Emily Hunt: The Grotto at Art Gallery of New South Wales on 26 June 2024, photo © Art Gallery of New South Wales, Jenni Carter

Emily Hunt, Homunculus trance, 2023–24. Calico, glazed ceramic, gold lustre, wood, nylon string, synthetic wig, found textiles, glasses and bronze. Photo: Felicity Jenkins

Like the psychogeographer who examines the specific effects of a geographical environment on the emotions and behaviours of an individual, Hunt’s connection to these places in Sydney, be they charged, haunted or just special, are available to us through the operations from which they resulted. The mural, the painting, the sculpture—each provides a surface for the immaterial, the divine, to materialise, for the esoteric practices of spiritualism to take a form. I’m thinking again of maps, and specifically scholar and priest Michel de Certeau on those made between the fifteenth and seventeenth century that used pictorial figurations of animals, ships and other characters to indicate the historical operations—military, political, architectural or commercial—from which they resulted. He uses the example of a sailing ship painted on the sea, indicating the maritime expedition that made it possible to represent the coastlines. The motif of the hand is one of these figurations in The Grotto. Like the maps of old, Hunt’s maps are not only constructed from received traditions and knowledge, but are also produced through observation, through the artist walking and wandering in Sydney.

Installation view of The Sydney Egregore Walk, 2023-24. Synthetic polymer paint, glazed porcelain and stoneware, gold lustre, pressed weeds and flowers. Photo: Felicity Jenkins

Since the mid-2010s, Hunt has made a series of clay hand sculptures that are modelled on bronze artefacts once used to worship the cult of Sabazius in the Roman Empire. An artefact of this series is part of one work at AGNSW, The Sydney Egregore Walk (2023-24), painted on the wall of the exhibition like a mural. Next to it is a hand holding a book called Kings Cross Black Magic, and further along there’s another hand coming out of a cloud holding a branch. I recognise this particular hand as the Ace of Wands from the Smith Rider Waite tarot deck, illustrated by Pamela Coleman-Smith. As I understand it, the Ace represent opportunities, a gift in the form of the suit literally in hand, which in this case, are wands (representing adrenals, inner fire). It’s the hand of a spirit/divine force/god/whatever you want to call it that holds the wand, and the trick, according to Tarot teacher Lindsay Mack, is that you have to reach out and take the gift. It’s not mandated but offered, and it’s up to us whether we say yes. The symbols of The Grotto are fashioned from the fabric of devotion between the hand that is earthbound and the hand unbound, the earthly and the spiritual. Intermixing these seemingly disparate categories is one of the ways the grotesque becomes more than a formal property or visual tradition in the exhibition. Perhaps, as art history professor Frances S. Connelly proposes, the grotesque is an action as opposed to a thing, an attempt to compromise the boundaries between two distinct realities. Connelly writes, “one way to understand the grotesque is to conceive of it as a boundary creature, existing only in the tension between distinct realities.”

Performance still of Emily Hunt: The Grotto at Art Gallery of New South Wales on 26 June 2024, photo © Art Gallery of New South Wales, Anna Kucera

However, what if one of these boundaries or identities, the so-called ‘earthly,’ has already been through a process of transfiguration? Hunt as psychogeographer has hand-picked parts of Sydney for their psychic or emotive resonances, making it soft and yielding to the embrace of the spiritual. When we enter The Grotto we arrive after multiple rounds of metamorphosis, the tension of the grotesque is gone, and here in the aftermath there’s no contradiction or ambiguity of a contrasting reality, for the earthly and spiritual have been thoroughly enmeshed. If the tension of the show isn’t between the spiritual and the earthly, then how might mysticism resist appearing simply as style or ornament? Recently, a review of the show was published on a Substack called Straying for the Morsel. The author, known as “Timcel” or “timwintoncellectuals,” discusses Hunt’s artist statement, in which she states that her endeavour is to “banish banality” and “re-enchant” our city by casting light on its features. He writes that “transfiguration of the commonplace” is a strategy in art, and the work, he says, “styles itself as an open invitation for Sydneysiders to reanimate the city with the glitter of lost silver.” Furthermore, “we are invited to become ourselves creators of an ‘art of life,’ and to make of our own reality a work of aesthetics.” In this context we are not only bringing something back to life—reanimation after all suggests that something is dead—but we’re doing so with only the “glitter” of silver, leaving behind the more robust properties of the chemical element. This reading frames mysticism as a “style,” indulging the shimmer of an element without the strength of its metal. Let’s go back to de Certeau and his understanding of maps. Those figurations of animals and ships and characters function as indications of historical operations that make the fabrication of a geographical plan possible. We can think about the imagery and symbolism in the exhibition in the same way. The individuals portrayed as marionettes and the map that is The Grotto are a testament to what can be built through practices of devotion and enchantment.

Gabrielle Chantiri is a writer from Sydney