Anne Charlotte Robertson, Five Year Diary: Niagara Falls, 1983, Super 8 Film, 27:00. Courtesy Harvard Film Archive. Photograph: Aaron Christopher Rees.

Talking to Myself, the Films of Anne Charlotte Robertson

Gemma Topliss

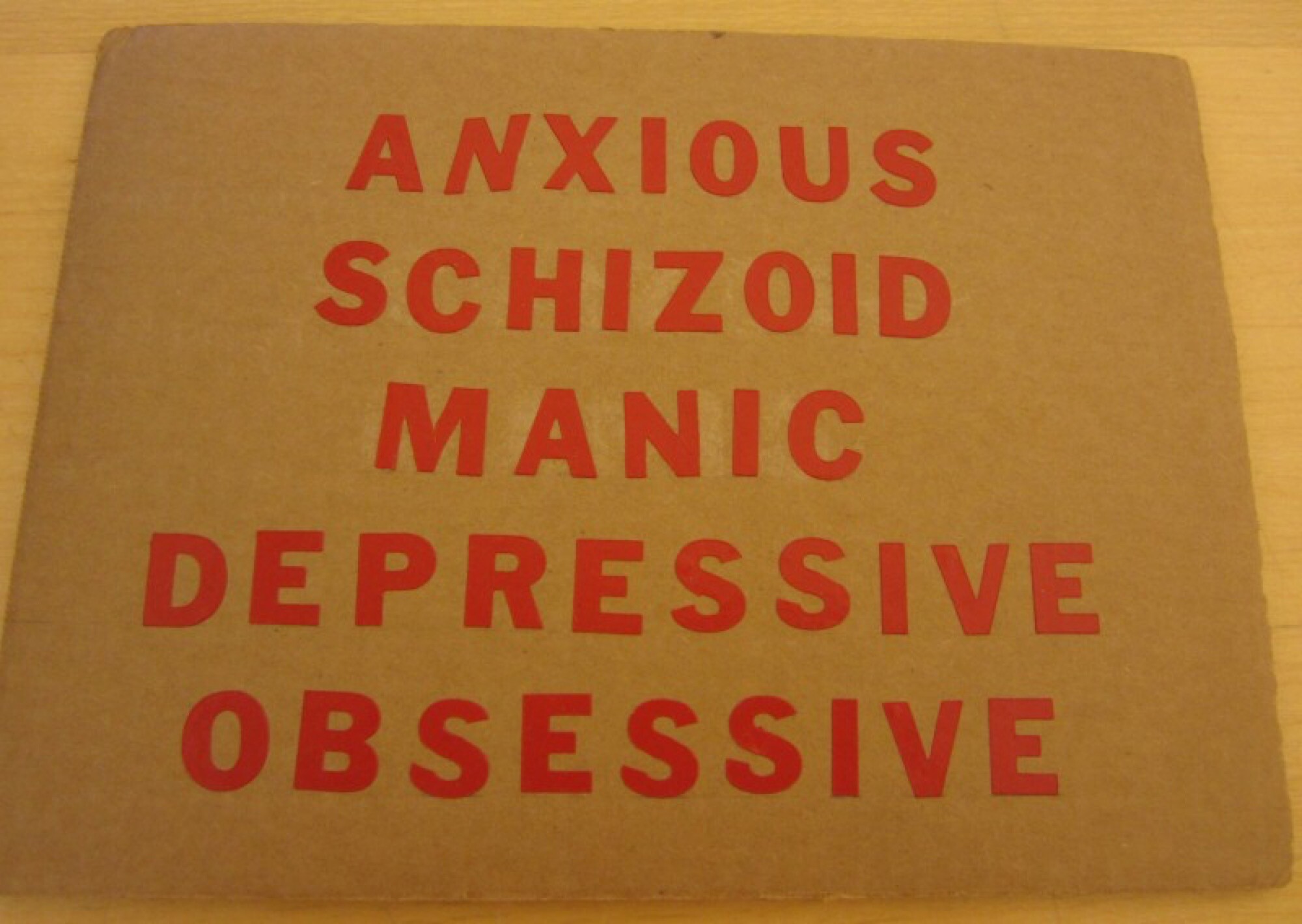

“She has been described as a manic depressive with schizoaffective disorder overlay but prefers to think of herself as a typical anxious, neurotic, with marked tendencies for fantasy, joy, and panic.” Anne Charlotte Robertson sometimes refers to herself in the third person. She began keeping a diary at age eleven and remained devoted to it throughout her life. What commenced in childhood as written diaries supplemented with annotated ephemera, plays, and essays blossomed in adulthood to include audio and Super 8 film recordings. Robertson completed an MFA at the Massachusetts College of Art in 1985, during which time her filmed diaries began. The culmination of the latter was the thirty-eight-hour epic, Five Year Diary (1981–97) composed of eighty-four reels, each approximately twenty-seven minutes long, with titles such as “Niagara Falls” and “A Short Affair & Going Crazy.” Robertson filmed almost every day of her life from the commencement of the project in 1981 up until it was completed in 1997.

Talking to Myself, the Films of Anne Charlotte Robertson at KINGS Artist-Run presents three films by the artist curated by Tara O’Conal and Nina Gilbert. Each Super 8 film is shown on a separate CRT TV, presented alongside each other with headphones. A reel of Robertson’s Five Year Diary is shown alongside two short films, Apologies (1990) and Talking to Myself (1985). Robertson’s seventeen-minute feature Apologies gives a voice to neuroticism, narrated by the artist’s apologetic ruminations. Robertson lets these apologies loose while continuously smoking cigarettes and sipping coffee. She apologises to her hypothetical future husband for her body, for her negligence of it, for smoking cigarettes and her resulting bad breath, for accidentally turning off the microphone in one scene and therefore failing to capture apologies uttered in a public bathroom. She delivers the type of vulnerability that is incongruent with femininity, the type that does not leave room for a saviour, but is instead alienating and repellent. Talking to Myself is far shorter with a three-minute run time, and depicts the artist duplicated, seated on a stool in front of a plain white backdrop. It looks as though the reel has been exposed twice, an analogue film trick allowing two scenes to be layered over one another. The result is an old-school Movie Magic illusion of two Robertsons, each sitting alongside the other. Interspersed with this scene, Robertson employs a black screen with the dialogue still running. In one such moment, Robertson wryly muses, “at least I won’t be over-exposed.” In photography, over-exposing an image means too much light has been let in, leaving a washed-out impression of its subject, devoid of details and distinctions. As a metaphor for depression, over-exposing renders a once vibrant existence faded and indistinct. As its title suggests, the only dialogue in the film is Robertson talking with herself. She has an erratic conversation with her filmic double. It is a carpet bombing of interjections rather than a collaborative conversation, one self talking over another.

Robertson’s intention was that Five Year Diary be shown in its complete thirty-eight-hour form, in a space set up in the style of her living room. She envisioned it accompanied by spoken-word performances and adorned with posters made by the artist alongside other artefacts. At the American Museum of Moving Image in 1988, it was shown alongside Robertson’s childhood ephemera. Such a gesture is transformative for the work, and yet it is an intention that is often overlooked in exhibitions of Robertson’s work. Instead, it is often abridged to suit more conventional film contexts. Historically, it has been more likely to appear in Avant-Garde film festivals than contemporary art contexts. Robertson described her vision for the work as “a home rec room fallout shelter.” During the twenty-seven minutes I spent with Niagra Falls from Five Year Diary, I tried to place it within such a space alongside a dilapidated stained couch, an ashtray full of cigarettes, half-drunk cups of coffee, wilting flowers, and bottles of medication. In reducing it to a screen, especially in a darkened cinema, the work becomes passive and perhaps less immediate. Five Year Diary is something that the artist lived rather than made.

Part of Anne Charlotte Robertson’s display for film screenings. Courtesy Harvard Film Archive.

Robertson’s intentions for Five Year Diary amplify this confusion between the boundaries of art and life. Where one begins and the other ends is unclear. While this may seem to be an over-explored conundrum, Robertson raises the question of whether her life is lived to produce the content, or if content is produced as a by-product of life. In actuality, it seemed, she owed her life to the content, citing that between hospitalisations for manic-depressive episodes, the act of filming kept her going. Today, this paradox belongs to the influencer. In most of these cases, it appears that life is lived in order to generate content. Without an experience being documented, it appears pointless or meaningless. For the influencer, the experience is located within its documentation rather than its lived context. The viewers of such an experience are not those that witness it in real time, but any impossible infinite number of viewers in the future, online. The imagined audience is the omnipresent and abstract third person. The photograph of the experience is more valuable than the experience itself. Long before this era, Robertson envisioned Five Year Diary be presented in a kind of living museum at a time where an enmeshed and co-dependant life-art relationship seemed avant-garde, or uncanny.

L–R: Anne Charlotte Robertson, Apologies, 1990, Super 8 Film, 17:00; Five Year Diary: Niagara Falls, 1983, Super 8 Film, 27:00; Talking to Myself, 1985, Super 8 Film, 3:00. Courtesy Harvard Film Archive. Photograph: Aaron Christopher Rees.

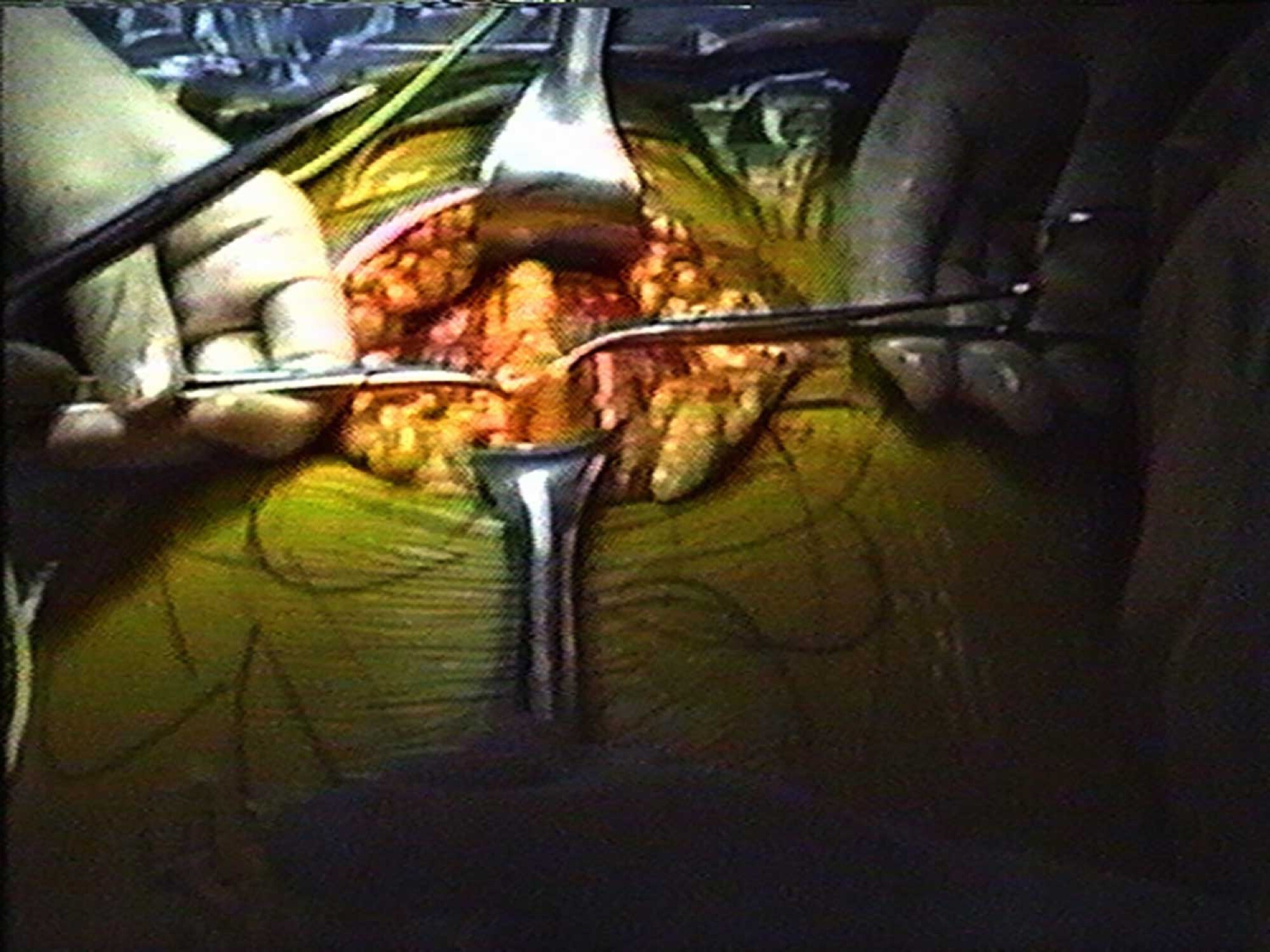

At the same time that Robertson was making and showing parts of Five Year Diary, American artist Lutz Bacher similarly used her interior as content for an artwork. Bacher’s film Huge Uterus (1989), documents a six-hour surgery the artist underwent to remove fibroid tumours from her uterus. Her New Age doctor provided her with the footage as an unorthodox gesture to help Bacher cope with the cognitive dissonance of such a significant physical episode. The resulting work is presented in its real-time duration, and in its original showing was configured to resemble a kind of body, with the monitor and audio components presented separated on the wall and floor of the gallery, linked by thin wires. The monitor rests on the ground, the proverbial loins of the gallery. The wires mimic veins, pumping the life force of electricity throughout the body, syncing image and audio. Bacher and Robertson both engage in the operating theatre. Diaries and the body interior are both things usually hidden, here made visible and presented by the artists. Bacher looked into her body to get out of her head, just as Robertson used what was inside her head to detach from her body. Five Year Diary initially began as a visual record of Robertson’s body, eventually she was able to look back upon all stages of her fluctuating weight with fondness, “I discovered I’d accomplished one of my goals, which was to look at myself naked and like myself at all the different weights.”

Lutz Bacher, Huge Uterus, 1989, 6:00:00 VHS and audio tape loop. Image: https://flash—-art.com/article/everyday-instability/

Whoever is presumed to be reading or viewing a diary becomes the core, or perhaps singular, subject. The third person eclipses the first. The second person speaks to relationality; the existence of “you” denotes the existence of the necessary “I” who identifies it. The third person alludes to both absence and omnipresence. Robertson’s viewer changes. At the time of commencing Five Year Diary, perhaps her imagined audience was her father, whose suggestion of telling a story with her film clearly stuck. As it progressed, it became a future hypothetical husband, envisioning the diary as some kind of gift or portal to understanding for her future spouse. In her own words: “It would be a trousseau you know, like a home movie made up ahead of time. So, in other words, I represent myself with them. They’re my true-so.” A trousseau refers to the belongings collected by a bride for her marriage, yet rather than belongings, Robertson is collecting small truths.

Other parts of Five Year Diary seem to be directed at Robertson’s long-time crush Tom Baker (the British star of Doctor Who, who plays its eponymous character). In fact, Robertson sent Baker multiple tapes from the Diary, including a scene where she scrutinises her nude body. Baker apparently held a collection of over two hundred dictionaries, (a fact Robertson recounts in an interview), which gives particular power to one of her first reels of the Diary where she films herself looking up the definition of “fat” in a 1936 dictionary. She credits Baker as being the reason she kept filming in the wake of a nervous breakdown and subsequent non-verbal episode, “The only thing that kept me going was taping for Tom every day. I gradually began to be able to talk again. And I still talk to him more than to any other human being. I talk on tape and I’m normal.” Robertson’s third person is changeable and malleable. It does not particularly matter who is watching, just that he is watching. Robertson’s celebrity crush eliminates any lingering relationality offered by her father or boyfriend. Instead, her third person becomes pure fantasy, an imagined Man.

Female narcissism is often misunderstood as an artistic device. It is presumed to be pure indulgence, lacking reflexivity. If it is truly a pathology, its primary symptom is femininity. The inward turn of so-called “female narcissism” may be less a preoccupation with oneself and more a mediation of third-person-ness. Female narcissism is the necessary counterpart of the male gaze. Female subjectivity is experienced less as hyper-interiority, and more as total dissociation: to view oneself from the outside, from the Other’s perspective. What is often identified as female narcissism is perhaps more akin to the experience of the sufferer of chronic pain. Rather than indulgence or self-importance, there is a sense of a patient at the mercy of their own discomfort, which they cannot help but be aware of constantly. Eventually, succumbing to the care of their doctor, or camera-cum-man, to be watched and observed, recorded, and assessed.

Gemma Topliss is a writer and artist from Melbourne.

This review was made possible thanks to the generous support of Meridian Sculpture.