Stuart Ringholt, Landscapes and Factories

Chelsea Hopper

Stuart likes to take things apart. Plastic chairs sliced in half, playing darts turned into paint brushes, crushed coke cans now used as aerosols. These objects, from the scatter series Low sculpture (2008), point to an approach innate to how Ringholt grapples with this sick, sad world as an artist. The act of dismantling, from mass produced objects to found printed material, continues to offer us curious results once put back together. Since the early 2000s, Ringholt’s collages have evolved from making slight or simple alternations, typically to a human body—the twist of the head or a smile turned upside down—to producing more chaotic, tactile effects. This frenzied style is notably found in the series Theatre Stills previously exhibited at Neon Parc in 2018, where magazine pages of Italian texts were pulled apart, remixed, and interwoven with large monochromatic images of classical art, architecture, ornate interiors and landscapes, with entertaining Monty Python-esque outcomes.

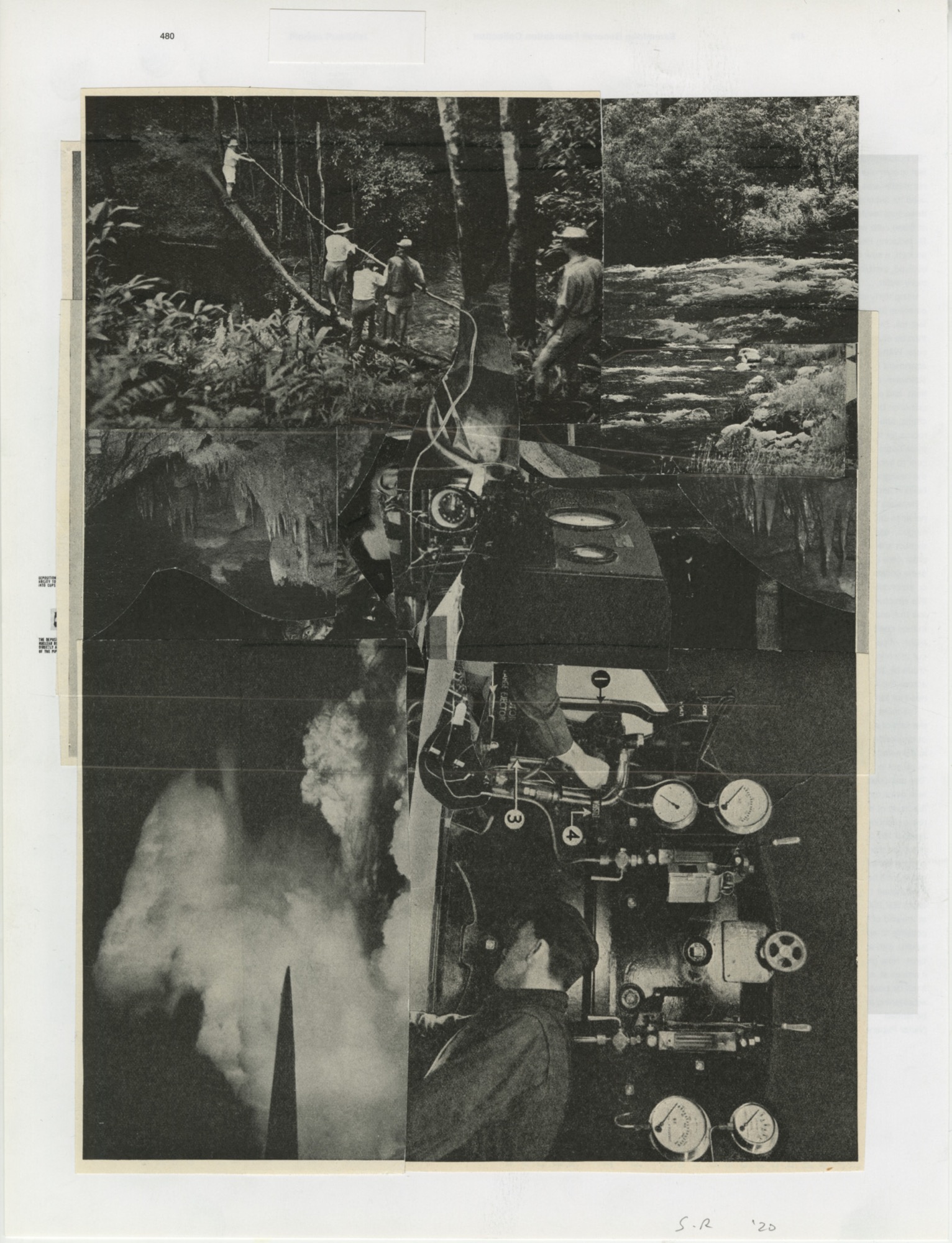

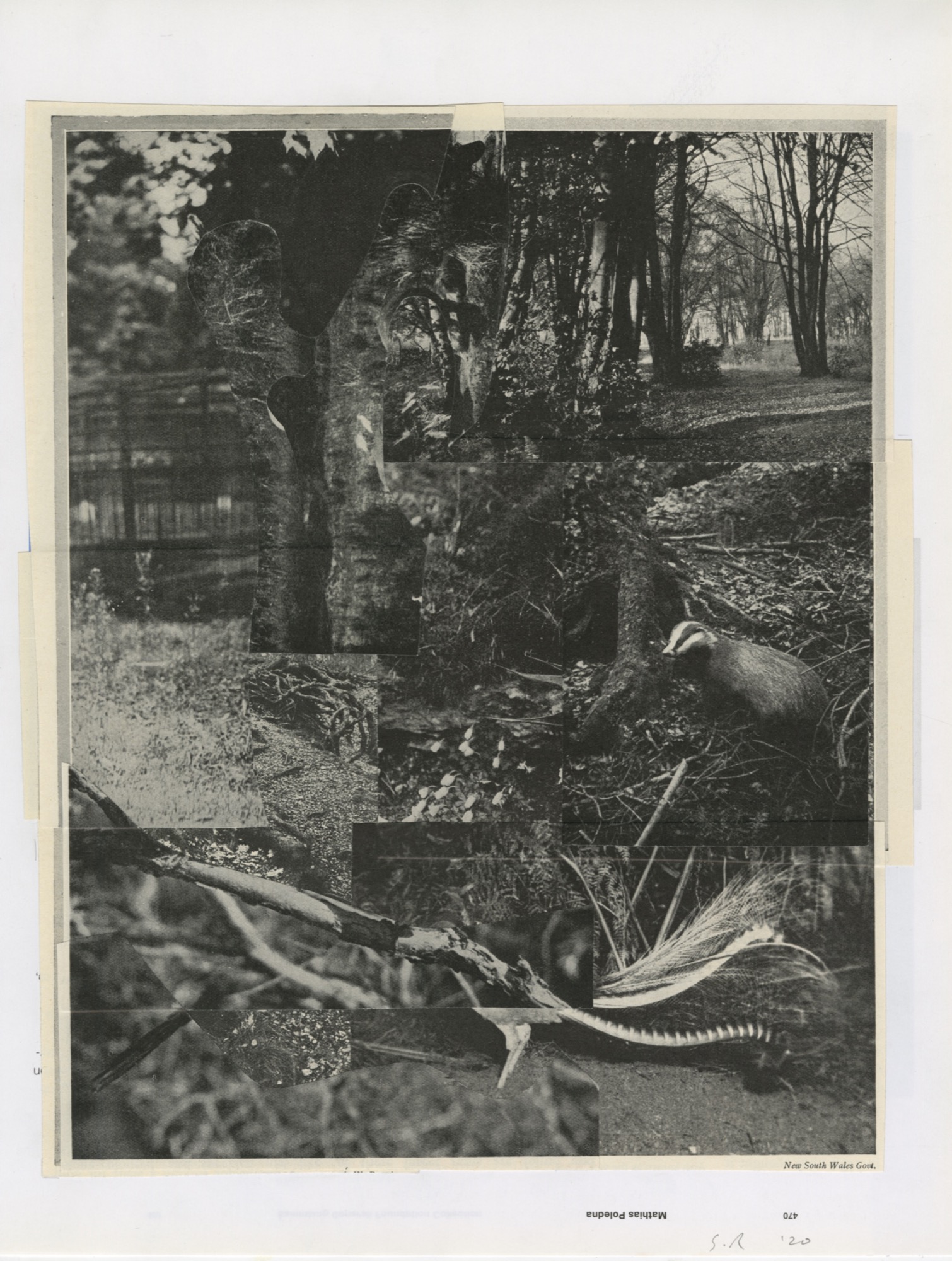

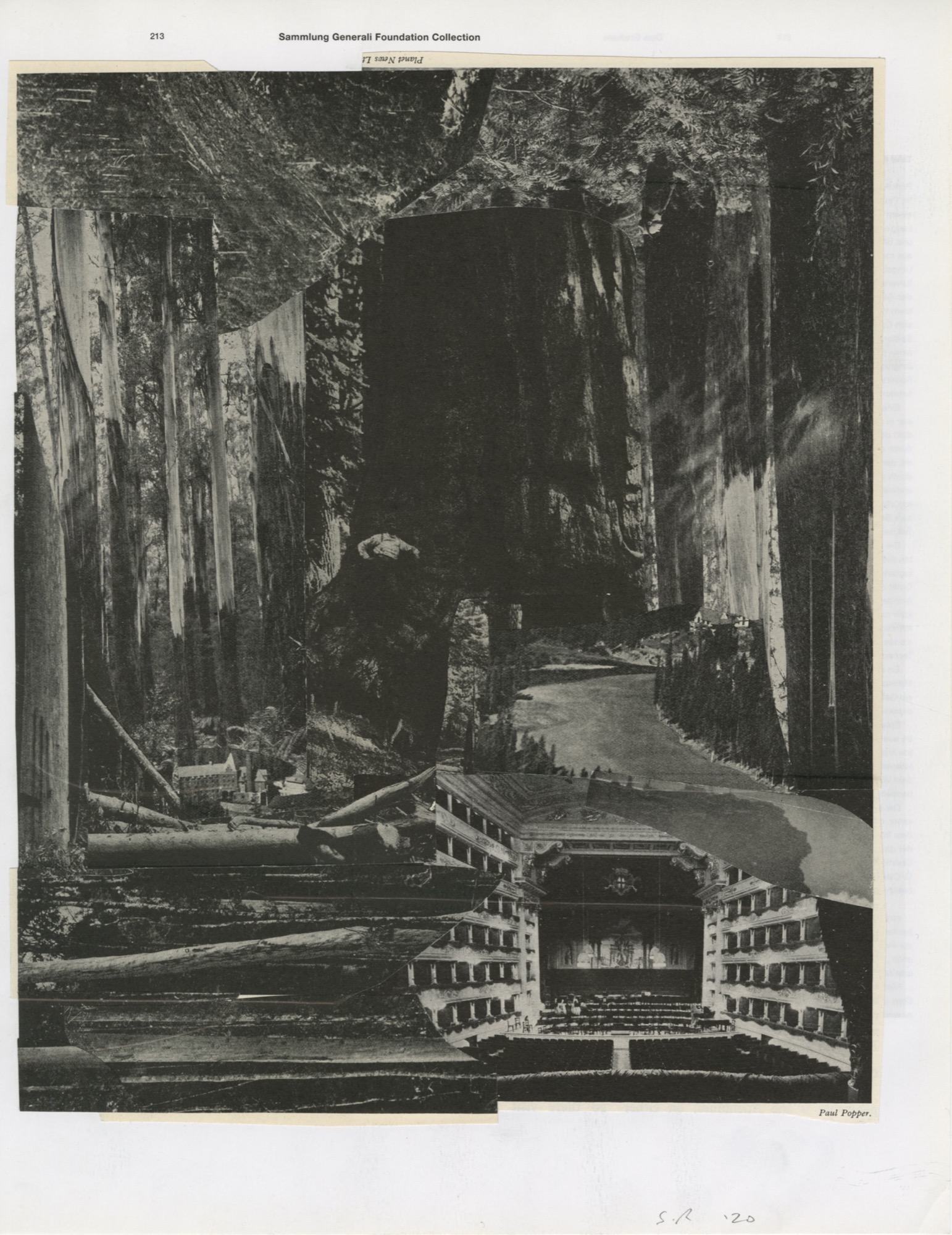

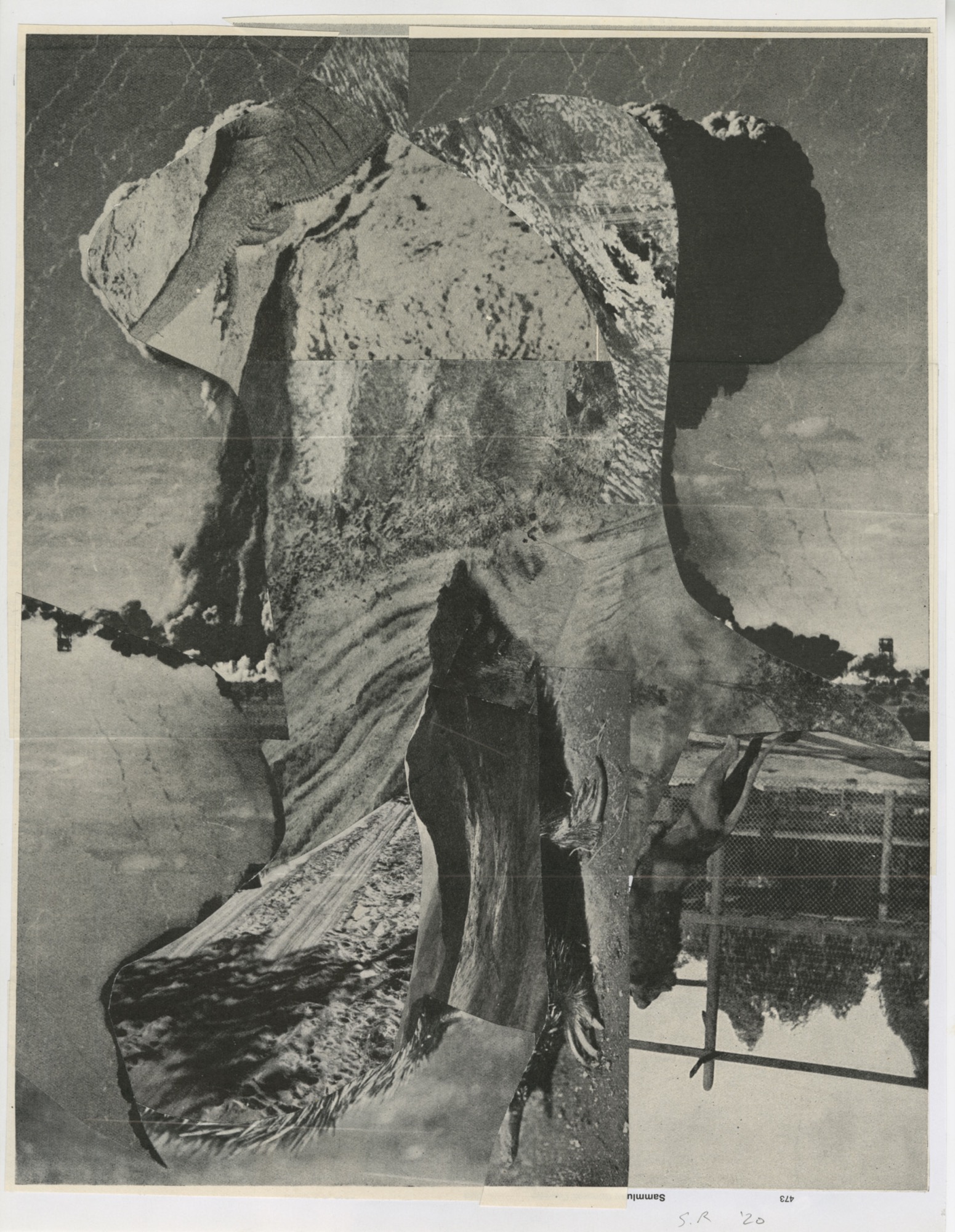

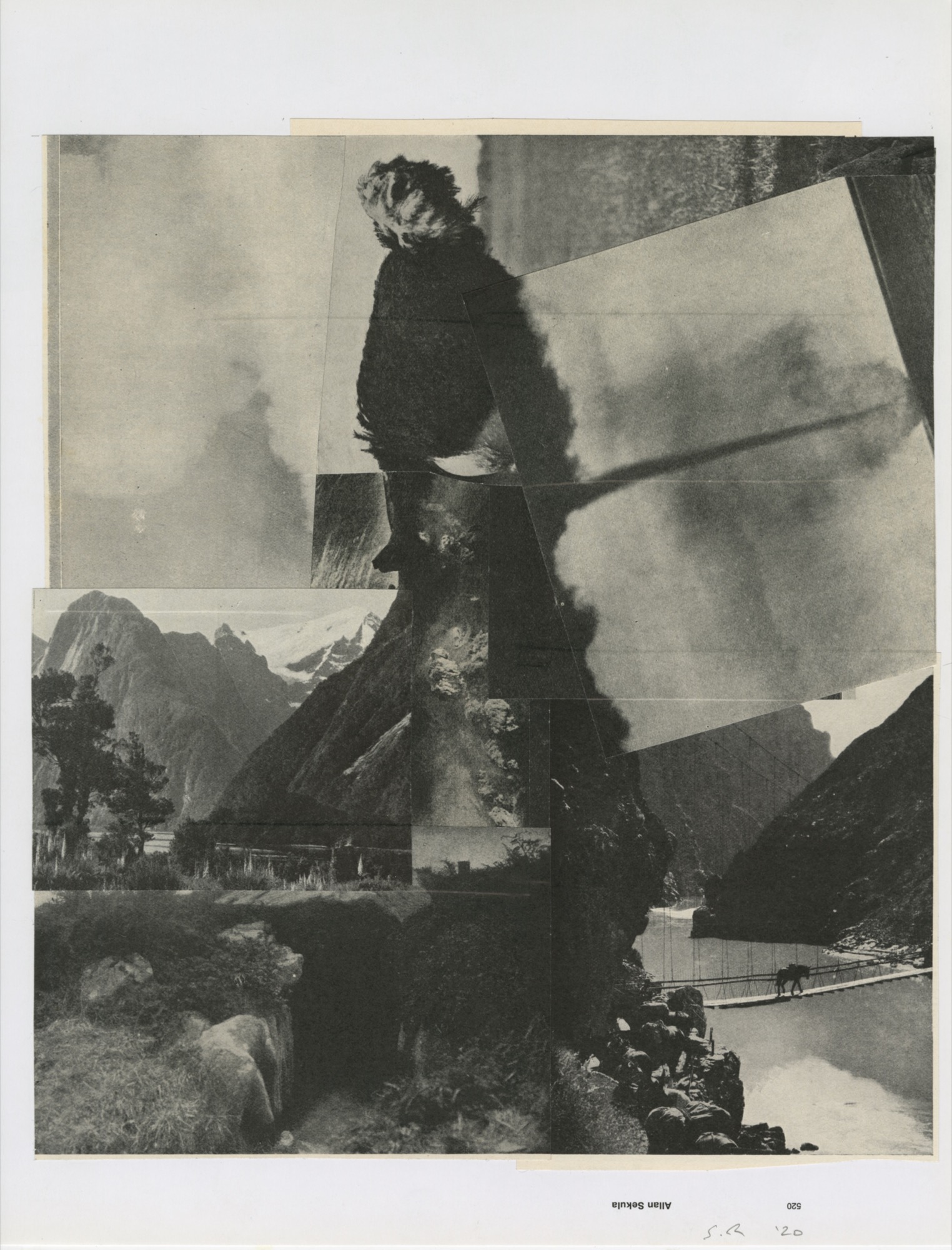

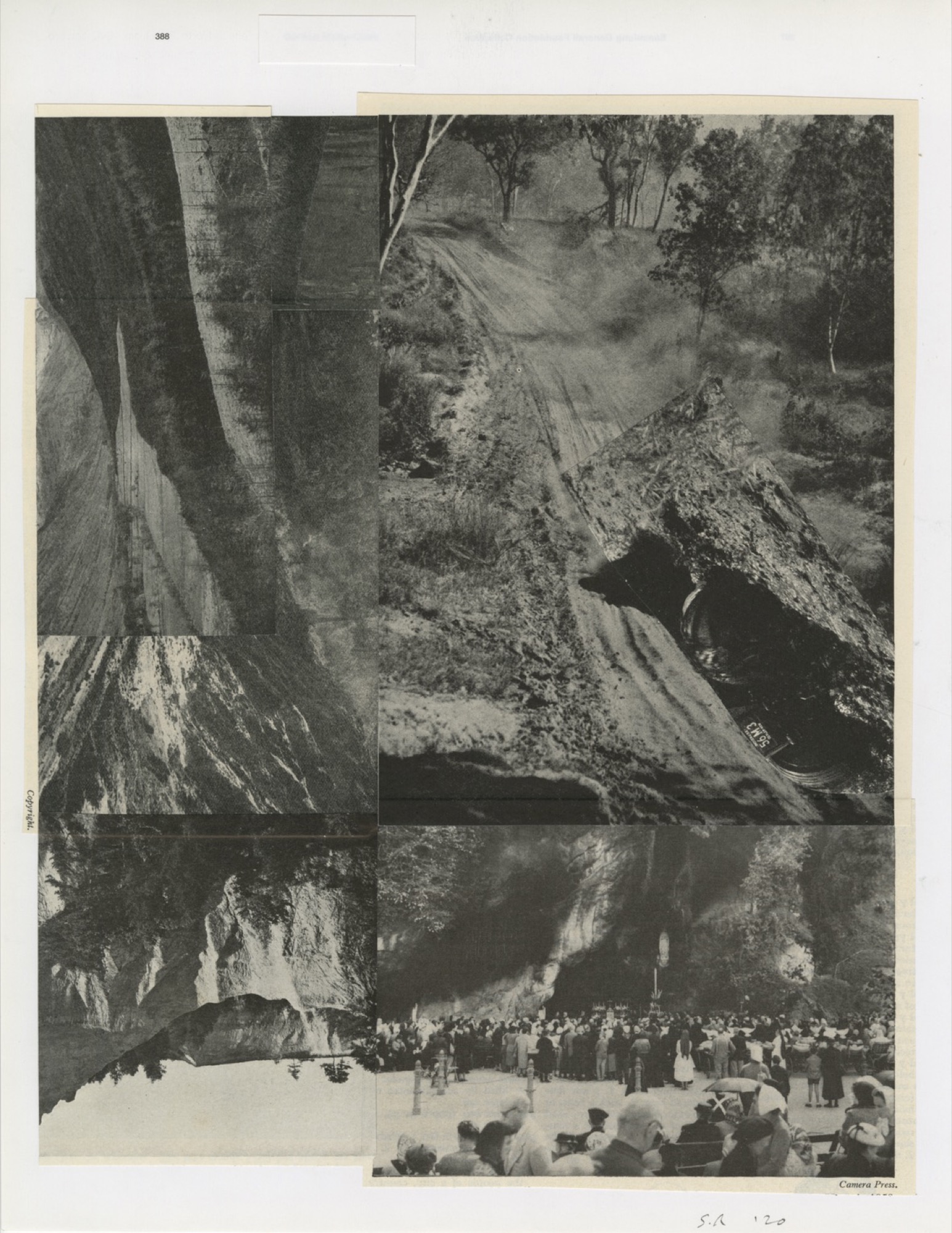

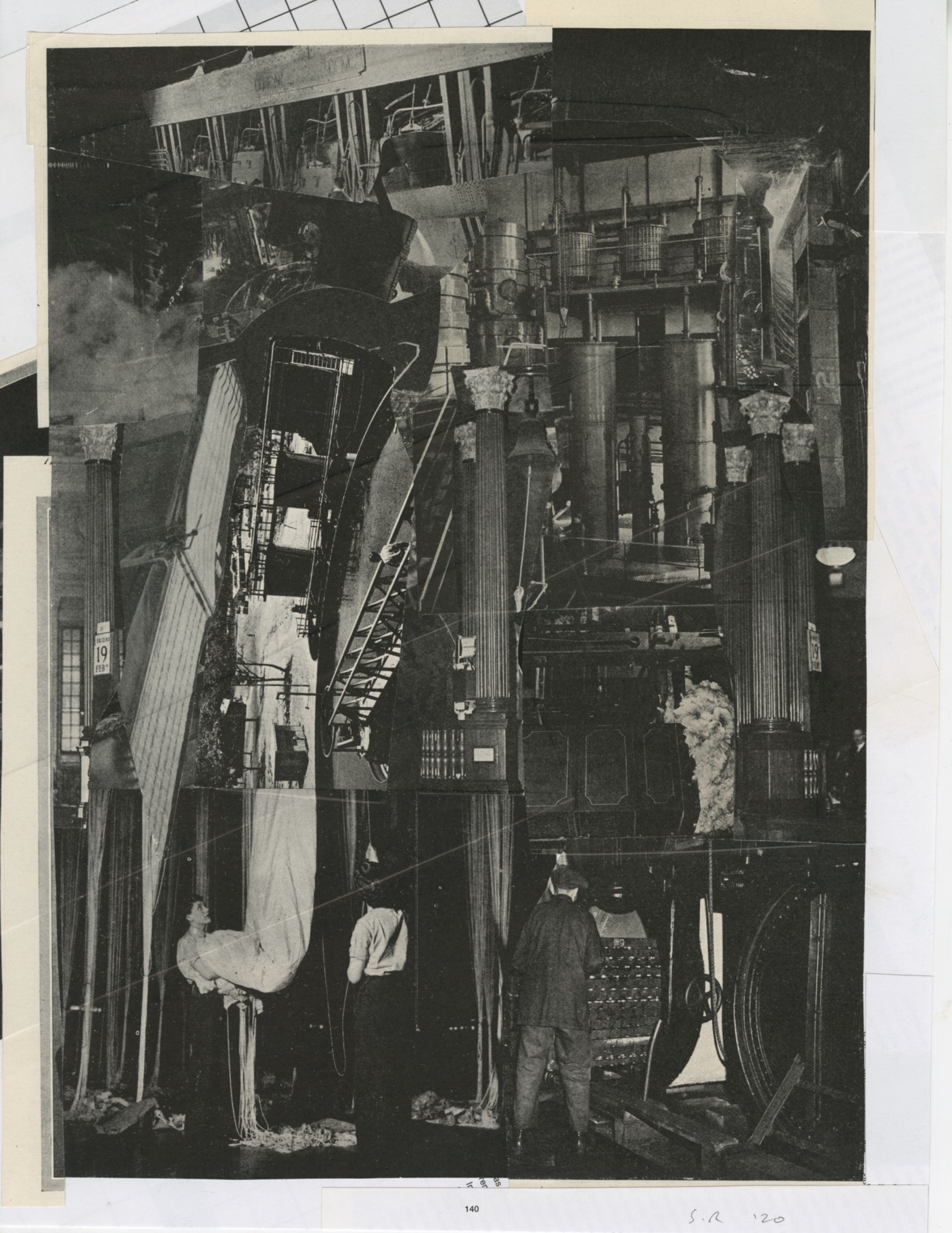

Ringholt continues his frenzy in a new series of twenty-three monochromatic collages simply titled Landscapes and Factories. Each collage is neatly housed in a hardwood frame, with them all lining three of the gallery walls in the back room at STATION. Thirteen are hung together in a row, while two groups of five sit on opposing walls, giving the space a sense of balance despite the busy, haptic nature of what’s contained within each work. These collages are primarily made up of grainy black and white images, sliced out of an encyclopaedia set and reworked to depict a plethora of subject matter relating to or referencing the series title. And—occasionally—not. In their new formations, a collision of forms, sections, shapes, perspectives and locations effortlessly coinhabit each page. The connections between the non-descript cuttings are almost always made through the tonal relationships of such high contrasting images. Other associations within each collage are easily made too. The subject matter in a corner of Page 480, for example, containing a long, thin pipe held up by a group of men in shorts, perfectly joins the front end of a pressurised machine taken from an entirely different image, and possibly a different decade altogether.

The encyclopaedia set, Newnes’ Pictorial Knowledge, consists of ten volumes, (even including its own dictionary and atlas, if you’re lucky enough to find them), was first discovered by Ringholt in an op-shop. Over several years, he sourced random assortments of copies on eBay in various volumes and editions, ranging from the 1930s to 50s, depending on luck. Now owning around six or seven sets, the striking red hardback covers, stacked up in his studio, are annotated on the front in thick black texta, as a shorthand to indicate the contents of each volume: “Birds”, “Trees”, “Landscapes”, “Plants”.

With over 400 pages in each volume, the black and white illustrated plates and photographic documentation are the fuel for these collages. When I ask Stuart whether there are any dates or signs as to where the set was printed or when the photographic reproductions were taken, he replied, “None… actually, there’s this.” Holding up one of the copies to his laptop, over Zoom I see a handsome bookplate citing the editors and location of the volume’s publication set in Tavistock Street, London. The editor, H.A. Pollock, I later discover, was the first husband of the famous British children’s writer, Enid Blyton, known for her mystery adventure novel series The Famous Five and who is also cited as an associate editor of the volumes.

Above the names of these editors, the book’s subtitle states it is “An Educational Treasury and Children’s Dictionary”, directly indicating who exactly the target audience of this “pictorial knowledge” is. In one of the volume’s contents page, chapters are dedicated to “Magnetism and Electricity — A Great Discovery and What has come of it”, another reads with a more moralising underpinning, “Famous Inventions and how they came to Pass — What Master Minds have done for the Good of Man”. There are even specific pages devoted to “The Romance of the Magnet”, “The Story of a Lump of Coal” and “Nickel, The Goblin Metal”. Is this how you make children interested in the industrial age?

It would be unfair for the reader to continue the inquest into the origins of the Newnes’ volumes that were repurposed for this set of collages despite their strange, quizzical charm. Put simply, it is beside the point. Stuart’s indifference—or lack of any real desire to know more about them—is more telling of where his efforts lie. He is not interested in the “meaning” behind the printed material, nor is the content that created these collages intentionally used to offer the viewer a summation of any global social, economic, or environmental urgency. Stuart is not here to teach us about the world we’ve ravaged, destroyed, uprooted, raped and pillaged—the damage has already been done. There is no moral lesson to learn here. But, of course, this reading can be made regardless of Stuart’s insistence. As with most contemporary art, it can be difficult to separate form and content. However, it’s almost impossible not be reminded of the ongoing real-world catastrophes regurgitated relentlessly throughout world news media. This week’s footage of homes being swallowed by floods in southern India, a recent Twitter post showing the desperate attempt to save the world’s largest tree by wrapping it in a fire blanket or even alarming reports citing the growing number of satellites and rockets contributing to amount of junk floating in outer space, all quickly bubble to the surface. Art historically too, another connection can be made between trauma and collage, the latter having its origins during the First World War, in cubism and dadaism.

Multiple incisions of smaller fragments from these images allow for oscillating perspectives to coalesce within each collage. In Page 213, an image of an empty theatre morphs into a river, mutates into a large tree growing in busy forest, and circles back to connect to a hefty stack of stripped, skinny logs. Similar transformations occur in Page 388 as a crowd of people stand in front of what looks like an opening to a cave, which quickly turns into a dirt track, then juts up against another landscape that eventually is overtaken by an upside-down mountain top.

Despite their autonomous grouping, a handful of the more abstract iterations take on absurdist meanderings: a mountain blends together cloud formations, a tornado and the back of an ostrich, while at the base of the formation, a lone horse crosses a rickety bridge stretched over a lake. In Page 473, bomb blasts from a nuclear testing site in South Australia, the leathery body of an iguana, the feet of an echidna and an arched back of a caged lion all outline other clippings of craters, river streams, and tree bark. “That one’s quite violent”, Stuart tells me, “It’s like a body being torn apart”. This comment prompts a question I ask later in our conversation about Ringholt’s ongoing interest in conflating subject matter.

A previous series of collages—and especially his collection of artist’s books—do this more overtly. The collage series Nudes (2013) fuses together pages from soft porn magazines with works of modern art. An early artist book, Aeroplanes and Speedboats (2005) seamlessly combines and reorders a speedboat catalogue with a book commemorating the September 11 attacks. Both share the exact same printed format, dimensions, and even paper quality. Flicking through the pages, leisure and tragedy, fuel and acceleration, disaster and pleasure create new and jarring associations. Untitled (Iraq, Barbie, Fashion) (2007) operates in a similar way, remixing and reshuffling three disparate publications: the history of Barbie, photo documentation of civilians in war-torn Iraq and expensive photoshoots from a glossy high-end fashion magazine. As Stuart manually selects, physically cuts and reinserts these pages, it is no surprise how the formal qualities of images still play such an important part of his decision-making process. These simple transformations unravel surprising and confronting visual connections that were once seen worlds apart. It is also worth mentioning, as a somewhat bizarre footnote, that the dimensions of each of these books were never physically altered or cut up to fit with each other—as if they were meant to be together all along.

The printed material, much like the Newnes’ volumes, now pulled apart and sliced up to make work, takes Ringholt several years to source. However once enough content is collated to sort through and play around with, the time it takes to create a collage can vary from a day or two, sometimes happening quite quickly, while others get left for weeks. Once framed, it only took half a day to install the series in the gallery. As soon as they were hung on the walls, Stuart tells me the series gave him a sense of completion despite much of the time it was on display coinciding with Victoria’s (hopefully final) lockdown. What mattered was seeing the work for himself, and invertedly giving oneself permission to move onto make something else.

I quickly realise I’ve spent nearly two and half hours looking at these images, where countless layers intricately overlap and intertwine with each other contributing to an addictive visual game of working out what exactly you’re looking at—or meant to be—resulting in a lot of double-taking, neck turning and eye squinting. The expansive nature of such agile images speaks to just how compelling and extraordinary this series really is (and also telling of the amount of time I spent in the gallery). There is an unassuming amount of nature and the “invention of Man” to pick apart. One favourite is a scene of a giant steam engine tweaked and jerked by two workers, as the ground beneath them opens out to a deep crater. In another, two women dressed in 1950s garb hold up what appears to be heavy, white, billowy parachutes immediately transforming into a lake, the conveyer belt of factory line and the pillar of a building. Mountains, mines, dams, lakes, rivers, shorelines, tails of birds and even the surface beneath the Earth’s crust swirl about on the pages. It’s ridiculous, nonsensical, an exercise in maximalist silliness, and I love it.

Chelsea Hopper is a curator and writer. She is an editor at Memo Review and Index Journal, an independent peer-reviewed art history publication based in Naarm/Melbourne.