Spowers & Syme

Victoria Perin

Monographs are out. Polyphony is in. The strongest curatorial statements being made in Australia seem to be that all artists have voices, and that the most legitimate way to represent that is to give them all space—a brief solo—before the chorus reasserts itself. This is a strategy designed for managing the discordance of contemporary art, but it has been equally applied to historical artworks. What do we do then when we only have two artists? Less space to hide in a duet. But more than that, what do we do when the two artists in question seem at first glance to be one artist? A solo sung by two mouths.

I’d forgive you if you find it difficult to tell the difference between the work of Eveline Syme (1888–1961) and Ethel Spowers (1890–1947), although I’ll give you the discriminating criteria later. In a decidedly non-hierarchical touring exhibition at Geelong Gallery, curated by Sarina Noordhuis-Fairfax from the National Gallery of Australia, Spowers and Syme are presented in a shared-biography model that is usually reserved for lovers (and occasionally rivals). In the two photographs that open the display, Spowers (in 1935) and Syme (in 1943) have their hair styled the same way; they could be twins. Both rich, neither married. Their money came from newspapers, and they were “uncannily” the daughters of rival press barons. In the accompanying catalogue Noordhuis-Fairfax skates their lives around each other, blurring the lines between them. E. Spowersyme. It’s an intimate display.

The commonalities in their art arise from their shared medium (linocut), their simultaneous induction into cosmopolitan modernism and the fact that they were “inseparable friends”. Together they did what they could to define modernism in Melbourne in the late 1920s and 1930s. In so doing, they and their peers have become pawns for art historians who would rank them higher or lower on the scale of the international avant-garde. This instrumentalisation is the background to Spowers & Syme, and explains why their friendship, and the artistic movement they participated in, is presented here as a community rather than a competition.

The modernist-art-as-competition framework is fully on display at The Picasso Century. Yet in a single-room gallery in Geelong, we are invited to remember that when we talk about a movement in art, we are usually talking about a group of friends. Behind each modernist ism is a group of people who knew each other, or knew of each other, personally. If we divorce artists from their connections—when we take people that knew, and worked, and lived near each other—and then turn that group into a great conceit within art history, we divorce those people from their social experience, the network that formed them, turning them into the visionaries and ciphers we believe we need.

Spowers and Syme belonged to the Grosvenor School of printmakers. Their membership in this group make their prints some of the most expensive in the world—a decade ago, a mania for the Grosvenor School linocuts saw one of Spowers’ works sell for £114,050 (A$174,700). You can see a wall of other Grosvenor printmakers on display at Geelong. Speaking of isms, the School and its treatment of subjects have broad connections to Italian Futurism and the British Vorticists, but I’m always struck by the contradictory Arts & Crafts nature of their leader, the instructor Claude Flight. While his work sought to represent modern figures doing modern and vital things, he was also moved by the vitalism of pre-industrial work and advised his students to depict work in the city and countryside. “Our museums are full of beautiful works”, he wrote in the late 1920s, “the crafts of the Middle Ages; all the best works of the greatest artists of all time are before us to study”. Futurism might be on the tip of your tongue when you see these works, but Flight was no futurist.

There now exists an international cottage-industry of research on the Grosvenor School, but some of the earliest dates from Australian scholars in the 1970s, such as Nicholas Draffin at the Art Gallery of New South Wales, Roger Butler, then writing for Deutscher Galleries in Melbourne, and, later, Stephen Coppel, who would go on to become the Curator of Drawings and Prints at The British Museum. Coppel’s boldest claim is that the Grosvenor School linocut movement was British-Australian, as a selection of mostly female students including Spowers, Syme and Dorrit Black, demonstrated a “mastery of the medium which surpassed Flight’s”. Here the language of competitive modernism comes sneaking back in.

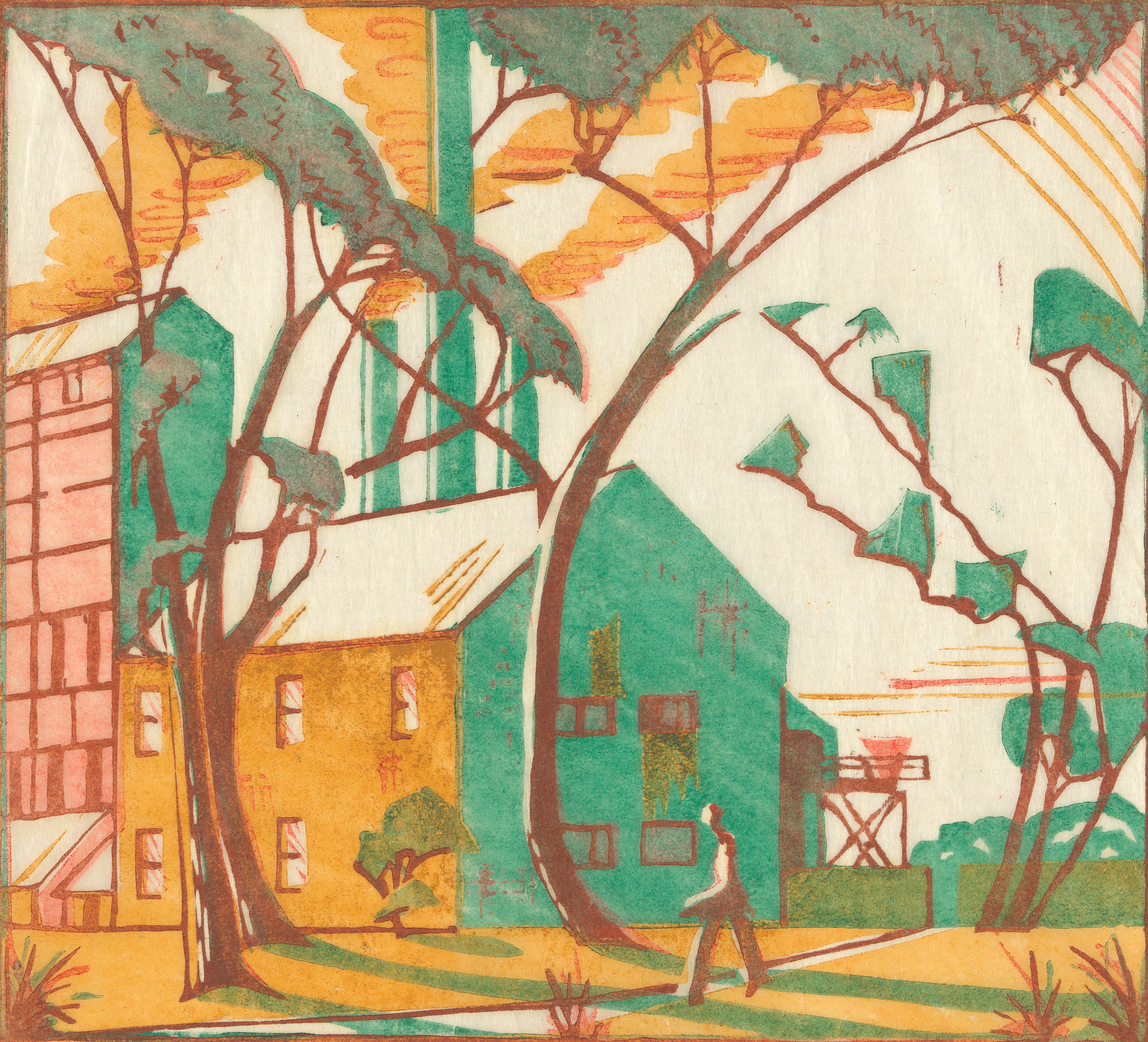

© Estate of Eveline Syme

Flight’s use of medium was idiosyncratic, and a lot of its core aims were based around anachronistic battles that are difficult for today’s viewer to discern. If you see these works and think ‘Japanese woodblock prints’ (i.e., ukiyo-e), you might be on the wrong track. While Spowers and Syme did first learn linocutting through books about Japanese prints, Flight’s technique was designed to reject the professional elegance of Edo ukiyo-e printing.

Flight advocated for a hand-crafted appearance. Relief printing, i.e. making a surface that stamps your design, had been dominated by the aesthetic of Japanese commercial print—illusionistic, exquisite, and refined. Flight’s DIY ethos rejected professionalised print aesthetics, advising instead that you cut linoleum with the sharp end of a broken umbrella rib, and that you variegate the saturation of your inking, so your image looked mottled and non-uniform. Grosvenor School prints always look like they were made in a flurry. They weren’t (it’s hard to rush the painstaking editioning process), but it was important that they felt hasty and dynamic in both aesthetics and subject.

Here is how you tell the difference between Spowers and Syme: Spowers was a Grosvenor School artist proper, Syme was not. For example, one of Flight’s core principles was the avoidance of an organising outline. A dominant key block, often printed in black, is fundamental to Japanese ukiyo-e prints. Flight said each colour in a print should be balanced equally with the other colours. Leave the domineering black, and never force an outline for your forms. Syme, however, couldn’t do without it. She had other interests and influences. Syme was, as Sydney Tram Line (1936) demonstrates, a dazzling colourist. She composed this image when visiting Spowers’ sister in Double Bay, Sydney. This exhibition suggests that she was activated as an artist by travel; she was moved to compose a print by landscapes as near as Warrandyte and as far as Siena and Hong Kong. She loved the innate flatness of linocuts, but was less bound to Flight’s technique, no matter how persuasive others found him.

© Estate of Eveline Syme

Without wanting to arch a rivalry here, Spowers is my gal. She took the vaguely contradictory lessons about dynamism, modern life and handicraft and used them to express what researcher Lorraine Sim describes as “choreographies of community and positive affect”. As acknowledged at the time by Melbourne educator and critic George Bell, her masterpiece is Wet afternoon (1930). Her other masterpiece is Bank holiday (1935), and Tug of war (1933), or maybe Swings (1932). The image of children was how she expressed modernity and the future, if not futurism. The woman who loved children; she had a sentimental streak, shown in some more illustrative, narrative work that Noordhuis-Fairfax resolutely refuses to segregate from the more “progressive” work. Here (true of early 20th century life, I imagine) modernism is allowed to stalk the border of Victorian sensibilities.

Now that they have begun to speak to us in different voices, we might consider again the fact that the model of a two-person biography is commonly restricted to romantic partners. This is for good reason. The paired biography tightly binds its subjects, making them psychologically inseparable to the reader/audience. You might expect, then, a robust laying out of evidence for and against Spowers and Syme’s romantic relationship, as can be found in Sybil & Cyril, the recent duo-biography of two Grosvenor School printmakers Cyril Power and Sybil Andrews, whose prints are on display in Spowers & Syme. Power, a fifty-year old architect, left his family to work alongside the twenty-four-year-old Andrews in 1922, before they proceeded to live as companions for two decades. At key moments, at the beginning and the end of her book, biographer Jenny Uglow interrogates Andrews’ late-life insistence that they were not lovers.

I had been told that Spowers’ gorgeous print, Resting models (1934), is considered Australia’s earliest nude of a lesbian couple, perhaps by the same uncited “contemporary commentators that conflate gender with sexuality” alluded to by Noordhuis-Fairfax in her catalogue text. Resting models is certainly an affectionate depiction of the female form, with closely observed hips and thighs that are slightly differentiated between the two comfortable sitters, one long-legged and lean and the other more Rubenesque. Noordhuis-Fairfax also has to debunk the rumours (again by “contemporary commentators”) that Spowers and Syme themselves were the sitters for Thea Proctor’s handsome print Women with fans (c.1930).

Noordhuis-Fairfax is one of our most literary artist-curators, and there is beautiful work here binding the lives of these apparent best friends, who were “new women”, bluestocking feminists, who never married or had any other known partnership. At the same time, there is a noticeable flinching away from the kind of conjecture Jenny Uglow allows herself in Sybil & Cyril. We must trust that the research, including discussion with the artists’ surviving nieces and nephews, has conclusively indicated that these women were not lovers. But little of that reasoning is shared with the reader. I find myself in the position of the gossipmonger, slinging slippery speculation to myself. What could one expect to know, I think, about the sex life of an aunt that died in 1947 or 1961? Future biographers can cite this review as a “contemporary commentator” next time.

Maybe it’s a lack of imagination that insists on privileging romance above devoted female friendship. And ultimately, notwithstanding the criticism of queer writers, such as Peter Di Sciascio, who has noted in an article about lesbian Australian artists that apparently “(the assumption of a subject’s) asexuality is clearly the next safest thing to (assuming) heterosexuality”, I am not hung up on bedroom facts. I am satisfied to know that Spowers and Syme were each other’s primary relationship outside of their respective families. Although little touches that might indicate the tenor of their friendship must also be hard to find in the archives. We miss information about their first meeting, or how they forged their friendship, and their daily routines. No letters between the pair are referenced, but youthful correspondence between art educator Frances Derham and Spowers is substituted prominently. Power and Andrews often wrote in each other’s diaries, filling out the entwined comings and goings of the day. This seems to be the type of intimacy, and moreover the type of primary source material, that a fully fleshed two-person biography requires.

This couple was just one unit among an international peer-to-peer group that cultivated a distinctive philosophy about the age they lived in. Noordhuis-Fairfax concludes that in Melbourne throughout “the 1930s Spowers and Syme continued to champion the art of the modern linocut”, via demonstrations, articles, exhibitions, society membership and their friendships with other artists. They sent prints to London and brought the prints of their international colleagues to Melbourne for promotion and sale. Rather than antipodean misunderstanding, Spowers’ divergence from the Grosvenor School is her strength: her feeling for joy, play and collective chorography. At the very least, the methodology of marrying artists into pairs forces us to consider artists as contingent entities. Artists are very rarely singular figures—in life or in their complex creativity. You can have your Spowers without your Syme, sure, but why would you want to?

Victoria Perin lives in Naarm and is a PhD student at the University of Melbourne