Architecture Makes Us: Cinematic Visions of Sonia Leber and David Chesworth

Hester Lyon

When the scaffolding of Sean Godsell's Design Hub was removed earlier this year, I felt a distinct sense of disorientation. As a familiar building, my relationship to it felt suddenly and unfairly disrupted by the rectification of its original form. I'd become comfortable in the scaffolding, gesturing out onto the footpath: a rare occurrence for a Godsell building, often defined by a distinct 'interiorness.' The scaffolding, through literal and administrative expansion, was more than a mere necessity of construction. It cultivated its own discourse: how buildings merge (or otherwise) into Melbourne's existing cityscape; how citizens manipulate territorial boundaries; and above all, where architects' authorship ends and public authorship begins.

Standing in another Sean Godsell building, Fitzroy's Centre for Contemporary Photography, we are the citizens of this gallery and artists Sonia Leber and David Chesworth echo these concerns. In Architecture Makes Us, the socialising function of architecture is explored through spatial tension and temporal distortion. Engaging with material, architectural, sonic and discursive framings, Architecture Makes Us brings together six video works in a mid-career survey. A product of the artists' often long, viscerally intense global residencies, the body of work is characterised by a porousness between natural environments and insidious human intervention; outwardness and introspection; collective consciousness and individual anxiety. The constructed relationships of exchange—between work and architecture; work and viewer; architecture and viewer; works and other works—manifest their own dependence. The result: a vast landscape of psychological states. Deliberate in its delivery, the audience must respond with inquisition, confusion, humour, cynicism and hope. Architecture emerges as a crucial cultural artefact leaving remnants of modernization, philosophical transformation and social change in its wake.

An active participant is made of both Godsell's architecture and us. As we traverse all four galleries of CCP, the state of our viewing and the physical state of the building begin to mimic each other. Symbiotic in accumulation, the curatorial path leads to a shared conclusion: the impossibility of distinct architectural and social realms. As we embrace the inability to view art without viewing its frame (read: proverbial frame—architectural, theoretical, historical, philosophical, social), we accept the value of ambiguity to comprehend our actions within the gallery space. The architectural fortification of Geography Becomes Territory Becomes, gives way to the tension between the final two works—the relative monumentalism of Universal Power House's enthusiastic proposition and the claustrophobic domesticity of Earthwork's invoked anxiety. Above all, we welcome the haptic response to viewing, no better articulated than in the exhibition's opening work.

Leber and Chesworth's newly commissioned Geography Becomes Territory Becomes, constructs its own architecture across gallery one. Produced during a residency at HIAP in Helsinki, Finland, the footage traces the contested island territory of the 18th-century Suomenlinna Fortress. What first appears as an eight-channel installation reveals itself as a single looped video. Displayed across eight identical screens at varying heights and angles, the single channel cycles at intervals. Predominantly cropped, at no point is cartographic orientation granted. The cinematography is predacious: panning, tracing and surveying the intricacies of Suomenlinna's rocky terrain. Periodically, the footage expands into broad, cinematic shots of the wider environment.

Here, Leber and Chesworth have literally fortified the gallery space. Theoretically, the video can be viewed in its entirety from one screen however extended stillness is not welcomed. In the display's rejection of totality, the audience is forced into active viewing, a participation that preserves the integrity of the work. In a fluid converging of the architectural borders represented on screen and the architectural elements created in the gallery, artist and audience enter into a shared discovery of an unknown territory. This exchange—of space, of knowledge, of cartography—is one of willingness to participate. We rely on the video for its mapping. And it relies on us to consume it through movement. And so, dependency is fused, only to be rendered futile and fleeting by the works pervasive soundtrack.

In a deliberate misalignment of audio and visual experiences, the sonicscape of Geography Becomes Territory Becomes echoes the dichotomy of its footage. A tension between visual intimacy and sovereign exclusion, the soundtrack ostracises us from the screen as we search for its source, low-down in the back corner of gallery one. As the soundtrack pervades the entirety of CCP, the exhibition is granted a tonal anchor. A compounding of beeps, blips and archetypal computer downloading noises, an overwhelming amalgamation of filmic references becomes reminiscent of a past's construction of a science-fiction future. Have we been transported to the future-dystopia of Andrei Tarkovsky's 1972 Solaris? Or Ridley Scott's overly referenced 1979 film Alien? Or does it all just become farcical when reminded of popular early-2000's kids show, Silversun? Without dissolving into the absurd, the anachronism of the soundtrack becomes overwhelming. The initial comfort of sonic cohesion, linking the visual differences of the exhibition's six works, deteriorates into successful discomfort. The multiplicity of its references defines a sustained dystopian tension, only interrupted with the additional headphones of Myriad Falls and Universal Power House, where the imagined and the real become all the more ambiguous.

Somewhat uneasily appended to the back corner of gallery one, Zaum Tractor: Eternal Pools and Zaum Tractor: Battle for the Future, a pair of stills from the original two-channel video installation, juxtapose the occupation of public and private spaces. In cohabitation, they examine the exchange between citizens and space to render architectural borders malleable. As Eternal Pools demonstrates a collective risk rationalised by containment, Battle for the Future reinforces the fluidity of psychological conceptualisations of space beyond physical boundaries.

Acting as a curatorial touchstone, Myriad Falls expands the cyclical distortion of past, present and future established in Geography Becomes Territory Becomes' inescapable soundtrack, to question our assumptions of linear time. Its gleaming aesthetic proposes an unending flux between the natural and the mechanical, destabilising our assumptions of time's forward-continuity and exposing what cultural critic Suhail Malik describes as contemporary art's “fetishization of presentness.”

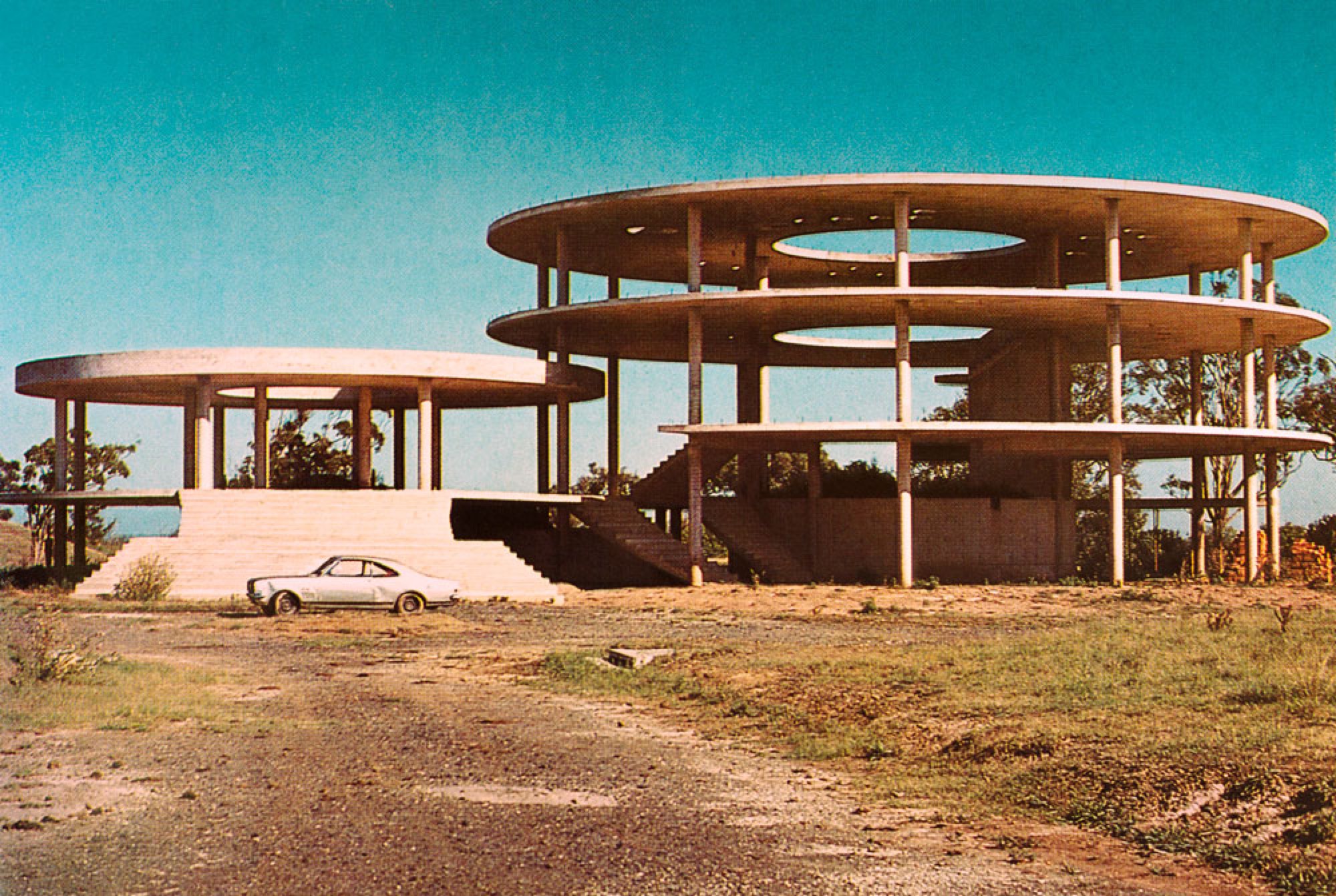

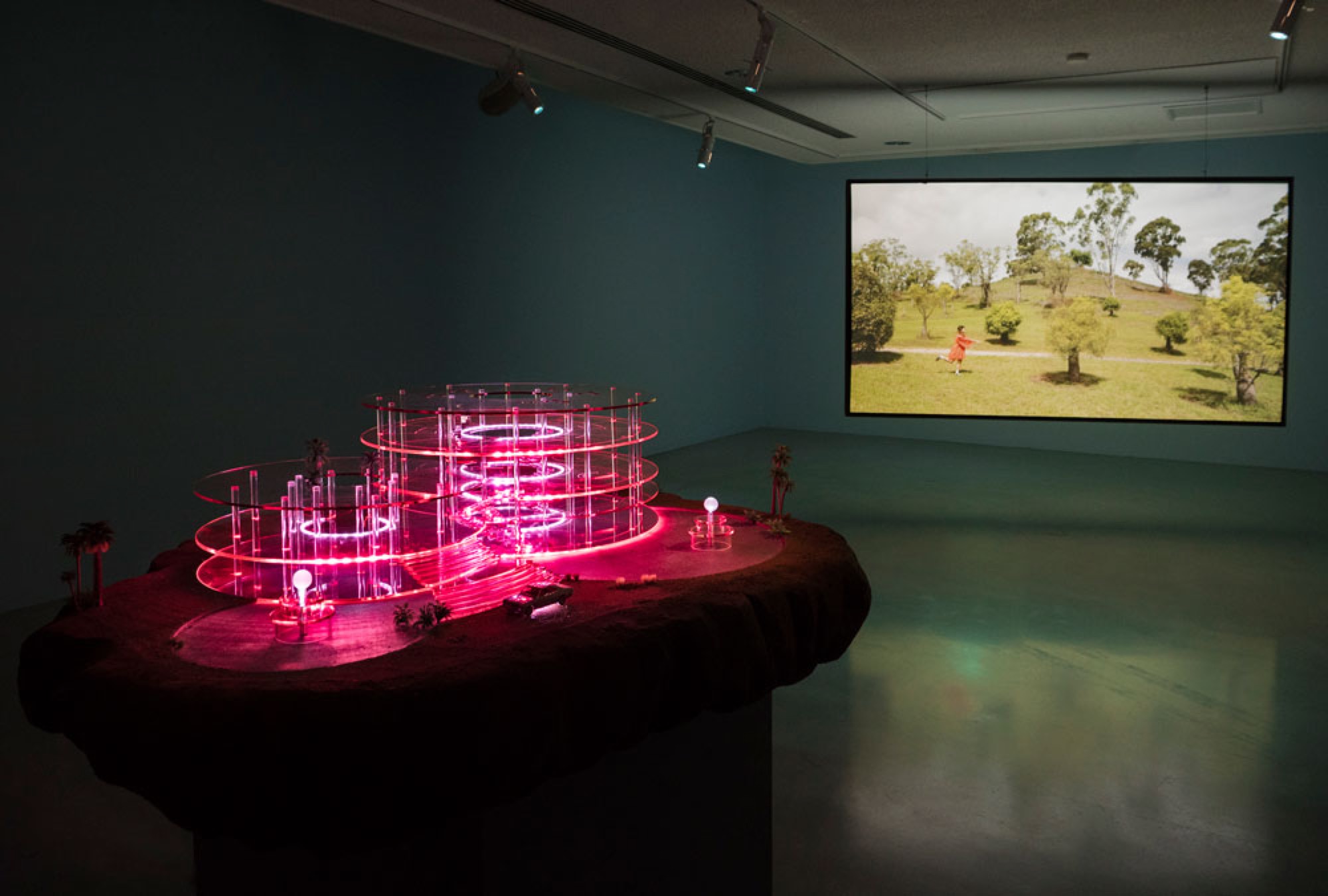

And so, Universal Power House: In The Near Future expands from gallery three, harbouring the anachronistic in the most totalising of effects. Commissioned by the Campbelltown Arts Centre, the work is a cinematic imagination of Polish immigrant Stefan Dzwonnik's Universal Life Challenge. Sarcastic in its immediate absurdity, a gesturing towards The Universal Creative Principle, “out of which, everything sprang,” becomes captivating in its enthusiasm. The illusive architectural remnant of Dzwonnik's ambition for worldwide consciousness, perched atop Campbelltown's Mt Universe, anchors the real and the imagined, the past and the future, through kitsch neon model and archival vitrine.

The playful aesthetic of the central video work see actors, briefed in Dzwonnik's Universalist principles, enthusiastically deliver monologues. Initially static, the actors progressively loosen into compulsive dance. The brazen bodily convulsions become comic devices in the exchange between the real and the unreal, propping up the deterioration of Dzwonnik's legitimacy. And, as humour and sincerity converge, a shared liberation of consciousness approaches. Intensified by a pop-disco soundtrack (experienced through headphones), the cumulative tension of the previous works dissolves into euphoria. Somehow, in this gallery space, we have been corralled into collective consumption.