Somewhat Eternal

Yuna Lee

First, I’d like to place Somewhat Eternal, Justine Youssef’s current exhibition at UTS Gallery, in relation to the current moment. Following Hamas’s 7 October attack, we have been witnessing a genocide unfold before our eyes, as the already besieged Gaza faces relentless and catastrophic bombardment by Israeli artillery and airstrikes. In just over four weeks, the far-right fundamentalist ethnostate has pulverised entire families and neighbourhoods and killed over 10,000 Palestinians. We are seeing the systematic erasure of an indigenous population under a colonial, Zionist regime which began long before 7 October, in 1948 (or as far back as 1917). In the face of these atrocities, we are also seeing a global movement mobilising like never before—protesting the ongoing Nakba and threatening the conditions of collective apathy, silence, and complicity which have, until now, allowed it to continue.

It is important for me to locate Youssef’s exhibition—curated by Stella Rosa McDonald (Curator & Manager of UTS Gallery), Tulleah Pearce (Assistant Director of Brisbane’s Institute of Modern Art), and Patrice Sharkey (Artistic Director of Adelaide Contemporary Experimental)—within this particular movement. This is precisely because it is an ode to a homeland (Lebanon) and family also marked by Israeli occupation. Unfortunately, nowhere in the exhibition itself is this context explicitly stated. While reference to her family’s lived experience and survival through “famine and military occupation” is made in the wall didactic, the details of this occupation and its relation to the broader regional conflict is left vague. Recently, UTS Gallery made an Instagram post for an upcoming workshop facilitated by the artist, which included a quote by Youssef herself that was more explicit about her family’s direct suffering under the Israeli’s occupation of parts of Lebanon between 1982 and 2000. The workshop, Youssef adds, “is a space to sustain each other as we protest, educate and call for an end to the siege on Gaza, the illegal occupation of Palestine and the ensuing risks that unfurl across our region.”

Amid the worsening crisis in the region and growing public pressure to speak up against Palestinian erasure, Youssef’s exhibition offers us not just a call for solidarity or hopeful futures. It also offers a concrete practice through which to understand these histories of subjugation. Somewhat Eternal asks us to cast our gaze wider to understand the interconnectedness of our struggles under the global history of settler colonialism and its normalisation in Australia through foreign policy. Youssef points to the complex ways we, as settlers living on stolen Aboriginal land, are implicated in, and also sustain, these cycles of displacement and dispossession. Only when we can recognise how settler colonial systems dehumanise us all, might we then alchemise our hopelessness, grief, love, and rage into resistance, and envision alternative futures.

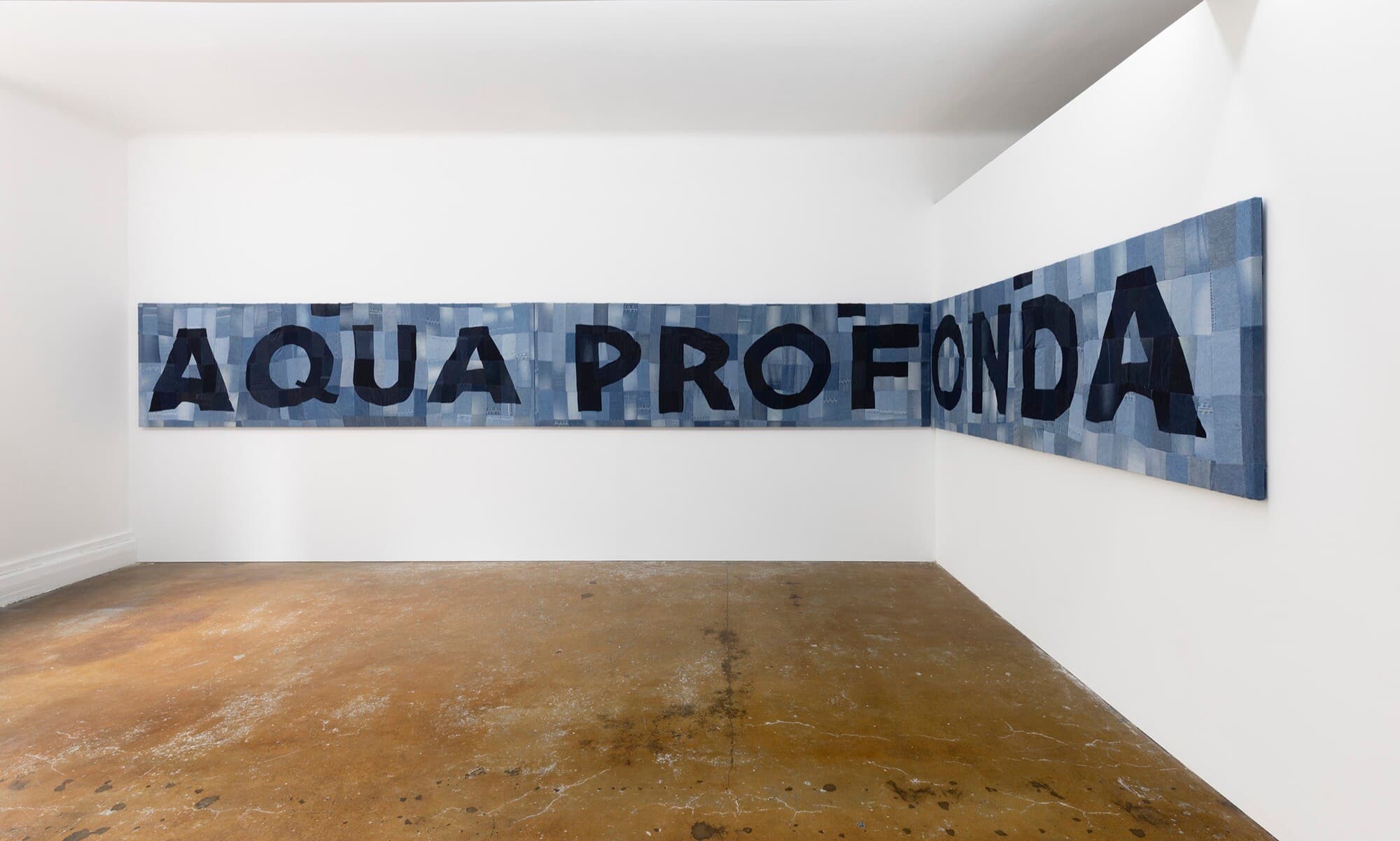

Co-commissioned by UTS Gallery, the Institute of Modern Art in Brisbane and Adelaide Contemporary Experimental (cities where the exhibition will also travel), Somewhat Eternal brings a much-needed perspective to the arts in so-called Australia. The exhibition presents a multi-sensory video installation, which comprises a three-channel video, scented and embroidered textiles adorned with silver charms, and an accompanying wall text bordering one of the gallery walls. The central component of the work is the video, which documents a member of Youssef’s family in Lebanon performing r’sasa, an alchemic practice of clearing the evil eye—a curse or hex believed to bring bad luck—through lead casting. In the video, the family member performs r’sasa over a WhatsApp video call with Youssef’s cousins in Australia. She proceeds to melt lead bullets on a spoon over a gas burner before casting it into water in which sprigs of parsley have been submerged. This process is repeated two to three times.

In the Instagram post mentioned above, Youssef discloses what is unique to her family practice of r’sasa: the lead they use is taken from ammunition reclaimed from Australia’s defence exports to Israeli settlements. Over the past six years, Australia has approved 322 defence exports to the state of Israel, of which fifty-two have been shipped this year alone. Our own Albanese-led Labor Government has given full economic, military, and diplomatic support to Israel, and consistently voted down on international efforts to hold it accountable. The question Youssef puts forward is simple: How might we, as tax-payers and settlers on stolen Aboriginal land, reckon with our own complicity in funding war crimes in Palestine, Lebanon, Myanmar, East Turkestan, Sudan, amongst many others? Understanding our complicity in replicating these insidious structures of dispossession, how might we move forward? For Youssef, a return to ritual and faith might offer speculative tools for worldbuilding and imagining beyond colonial paradigms.

Hung and tied together alongside the glass exterior of UTS Gallery, five embroidered faux mink blankets are scented with four hydrosols produced from the steam distillation of plants using a process the artist has inherited matrilineally. Youssef has long used plants as a means to interrogate the histories of settler-colonialism, and the contradictions that often arise from the multiple layers of displacement, exiles, and dispossession occurring within a particular place. Her distillation practice using plants with charged colonial histories can be seen in earlier iterations like an other’s Wurud (2017), which centred Burnet Rose, or more recently with the Hawai’i Triennial 2022 titled With the toughest care, The most economical tenderness, which centred Blessed Milk Thistle. This work marked her first artistic departure from Australia with an opportunity to connect the plant’s shared histories of land subjugation in another settler colony like Maui.

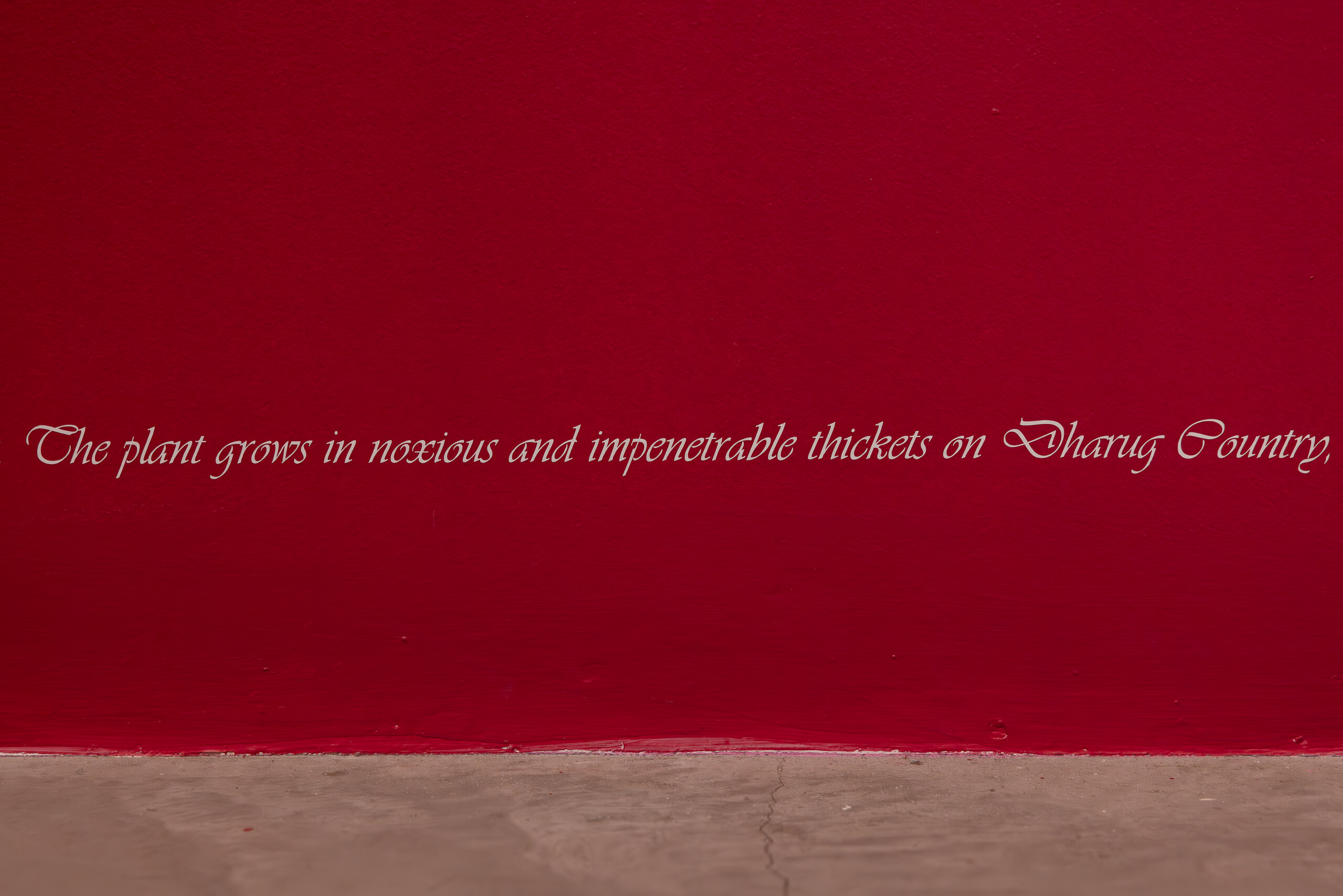

Here Youssef has included Burnet Rose (Rosa spinosissima), Damask Rose (Rosa x damascena), Lebanese Cedar (Cedrus libani), and Blessed Milk Thistle (Silybum marianum). As revealed by the small wall text bordering along an adjacent wall, each plant has been selected for its complex relation to displacement, subjugation, occupation, and renewal in Australia’s settler colonial histories, as well as sharing interwoven and layered histories with Lebanon. Plants native to Lebanon such as Blessed Milk Thistle and Lebanese Cedar, for example, held much reverence for their medicinal, divine, and spiritual properties. In the case of Blessed Milk Thistle, however, much of this traditional knowledge surrounding its therapeutic uses has been erased through its displacement, after early British colonialists introduced and harvested the species on Dharug Country. Under our climate, it grows in impenetrable thickets and has become invasive and highly noxious.

Scent continues to play a vital role in her practice as its own form of speech that can make visible the immaterial or otherwise unseen. Through distillation, Youssef believes that a scent has the power to embody prayers: like a ghost, it has the power to hold and haunt the space of the plant’s possessor. The scents distilled from each plant, then, come to embody and reveal the hidden botanical legacies that offer sharp parallels to the settler Australian identity. Like the use of lead in r’sasa, tending to plants with material traces of colonial histories and transmuting them through an inherited distillation process can be seen as a way of honouring the restorative ways of Youssef’s family, while also forging new paths for shaping our material and immaterial relations to land and place.

Somewhat Eternal evinces a fervent belief in alchemising and making as a means of forming gateways to new realms. The exhibition is a labour of love that is palpably felt down to its meticulous details: the lingering aromas of the hydrosols and bordering wall text, which act as protective spirits or talismans; the silver charms of an angel, a heart locket, and blue evil eye hanging off the blankets, to ward off bad spirits and energies; the ribbon ties which lovingly hold the blankets together; down to the bundled faux mink blankets offered as seats for viewers throughout the main hall of the gallery. Details such as these reaffirm a level of consideration, care, and intention that Youssef practices not just as an artist for this exhibition, but as a person moving through this world.

Whether through the practice of r’sasa or distillation, Youssef shares an innate belief in the endurance of ritual as a way of building values and discipline that can help us reshape our relationships to the structures we live in. She reminds us that what will be left of us on this earth is the spirit of the actions we take here and now. In the face of overwhelming grief and rage, she teaches us that radicalising into a consciousness that can locate problems in interconnected systems and not in people, is one of the most profound ways to heal. That understanding and reckoning with our complicity within a place so riven with contradictions and the violences of multiple uprootings and displacements is only the first part. That we must use the privilege of the life afforded to us by our parents to speak up against the silence. It is an honour to view the world through Justine Youssef’s lens and to have my consciousness heightened. And for that, I am eternally grateful.

In solidarity with Palestinians around the world, I share these resources to collectivise towards a different kind of world:

A comprehensive document listing the ways we can collectivise and meaningfully engage with the Palestinian resistance in so-called Australia. It includes: general educational resources, MP and government contact details, upcoming rallies and protest safety information, Palestinian social media accounts to follow, BDS Australia information, and much more.

● All the Walls Will Fall: 2023 Palestine Liberation Resource List

● Solidarity with Palestine: Free Resources and Further Reading from Verso Books

Yuna Lee is a writer, editor, and artsworker based on unceded Wangal and Gadigal land.