Shock & Ore

Lauren Burrow and Tristen Harwood

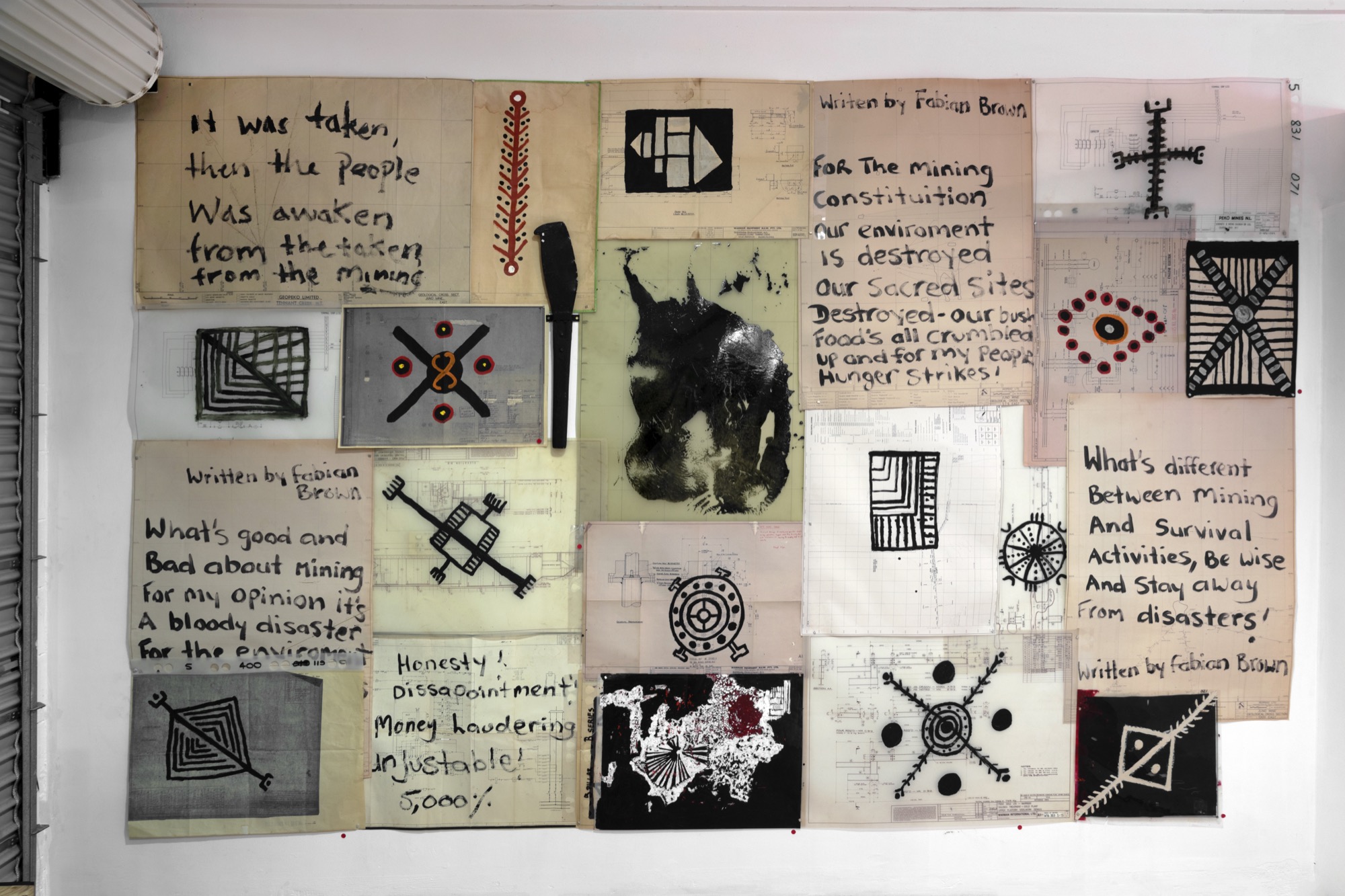

For the mining

Constitution

Our environment

Is destroyed

Our sacred sites

Destroyed – our bush

Foods all crumbled

Up and for my people

Hunger strikes!

– Fabian Brown, Tennant Creek Brio

Shocks come from somewhere and flow somewhere else. The Tennant Creek Brio (Rupert Betheras, Marcus Camphoo, Lindsay Nelson, Joseph Williams, Fabian Brown, Jimmy Frank, Clifford Thompson and Simon Wilson) are engaged in acts of picking up, interpreting and re-working the debris left in their path—in the fallout zone. A constellation of materials left by the wayside of pastoralism, extractive capitalism, globalism and mining are assembled in Shock and Ore, an exhibition by the Brio split across two galleries on Larrakia Country/Darwin: Charles Darwin University Gallery and Coconut Studios.

Tennant Creek sits on Warumungu lands, in the heart of what is delineated by settler boundaries as the “Northern Territory”. In a speech at the exhibition’s opening, artist Jimmy Frank described the impact of colonial encroachment in Tennant Creek as a protracted and repeated shock. His family’s Country was known for its vast, flat and hard ground. The creation of sacred stone sites for Warumungu is connected umbilically to open sky through the ancestral figure of the flying fox, who flew through the air and made black rock (ironstone)—formations of deep cultural significance.

In the early to mid 1900s, in the wake of the violence of pastoralism and the erection of the Overland Telegraph, Peko Mine, one of the largest open-cut mines in Australia was established at Tennant Creek. At this time, the ancestral black rock became the specific object of capitalist desire as a rare form of ore containing iron and gold. The millennia of slow geological and cultural formation of the lands were fractured instantaneously by settlers using Alfred Nobel’s patented dynamite, a highly volatile and powerful substance manufactured in Melbourne, transforming the flat Country into an unfamiliar, sundered place of deep holes and hills of piled tailings.

One of the first works encountered by visitors to the university gallery is Frank’s Mining martan (2022), a vitrine containing five handmade tools. Of the work, he says:

The rocks are hand-wrought shards from underground mining samples collected at the old Warrego mine site. I’ve combined this with the traditional spinifex resin handle. Traditionally, these were used for cutting up meat and occasionally for ceremonial use.

The spinifex resin also belongs to a story of familial inheritance and ancestral creation told by Frank. Each shard of sharpened stone is gripped by a piece of hand-moulded crimson resin, collected from the stems of spinifex grass, fused into a strong mass through heating.

These works are pointedly museological in their display, recalling Stephen Gilchrist’s sustained critique of the competing chronologies of biological time, ancestral time and museum time inherent in the naming of such objects as Aboriginal “artifacts”. As Gilchrist has noted, when museums describe things as artefacts, they are deprived of cultural context and inscribed with museological narratives. The attribution of the label “artefact/s” to Indigenous cultural objects severs them from the sociality of their creation, turning them into something else, possessed, rigid. In this sense, rather than preserving culture the museum might be understood as a kind of cultural graveyard.

In this context, Frank’s stone and spinifex resin objects conceptually overlap with important ancestral narratives and cultural milestones, including colonisation, specifically the onset and ramifications of mining at Tennant Creek. Implicated within the life cycles, spans and ways of Indigenous men, the objects signal to the vital cultural subjectivities often buried in the museum.

Moving further into the exhibition, the Mining martan is pitted against technology on the massive scale of heavy industry. Pinned to the walls surrounding the vitrine are dozens of large, old mining plan prints that have been re-inscribed by various Brio Artists. The plan prints present information pertaining to the geological surveying and daily functional activities of the Peko Mine, which devastated Warumungu Country from 1939 to 1981 and is now being restarted by Enmore Limited. Topological maps, aerial photographs of the land, graphs, charts, maps of buildings and diagrams with instructions for operating mining machinery are printed on acetate and paper, yellow with age. Disused remnants of mining bureaucracy, these prints are poetically reinterpreted by the Brio artists, who paint and draw directly onto them, reinstating their knowledge of the land over the instrumentalised relationship embedded in the logic of the mining plan.

In Joseph Williams’s Signs of Life I-X (2022), bold shapes and dots are painted in opaque acrylic paint onto the plans. Similarly, a large black, red and orange circular form in Lindsay Nelson’s Ceremonial motif (2022) obscures would-be vital information on a diagram for a “WARMAN SERIES ‘A’ PUMP COMPONENTS DIAGRAM” for someone wishing to operate the pump. Nelson’s and Williams’ painted shapes, encoded with symbolic and ancestral knowledge, present anti-maps and anti-diagrams of place that cannot be read in purely metric or visual terms but must be understood within the specific context of kin, ceremony and ritual.

The use of thick acrylic paint and enamel is a through-line between many of the works by the Brio. Fabian Brown and Rupert Betheras’ Wound Series (2022) is a suite of found TV monitors, often smashed, their screens painted with red acrylic smears—an overblown gesture emphasising the material weight of digital imagery and the damaging cycles of technological waste in Tennant Creek. The work arrests the flow of the broken TVs away from peoples’ homes and into landfill, the pollution/occupation of Indigenous ground “elsewhere”.

Re-figuring the TV screen as a wounded body itself (rather than as a potentially morally, psychologically and physically damaging instrument for human bodies) recalls Indigenous scientist and thinker Max Liboiron’s theory of “plastic as kin”, wherein a ubiquitous, ecologically damaging substance like plastic challenges the often-fetishised concept of kinship as an inherent set of “good” relationships. Liboiron asks what to do with “bad” kin, and Brown and Betheras’ Wound Series similarly problematises flows of waste and the sicknesses of technology in their community.

The Tennant Creek Brio’s formation is part of the legacy of the men’s shed movement. The movement began in rural NSW in the 1980s in response to a growing need for a communal approach to addressing the mental health issues of older men in small communities, with ailing mental health in retirement or as the direct result of having fought in the Vietnam War. Based on the figure of the backyard shed, a space of vernacular creative production—fixing lawnmowers, restoring furniture, tinkering—men’s sheds emerged in contrast to the patriarchal impetus for men to repress vulnerability and instead maintain their own psychological wellbeing through processes of interpersonal care, rather than passing responsibility onto women. Along binary gender lines of societal roles, the men’s shed addresses the symptoms of men’s mental distress as expressed in the form of social issues of domestic violence, substance abuse and related criminalisation. It can be thought of as therapeutic and gendered mutual aid.

The Tennant Creek Brio combines the men’s shed approach with elements of the remote Aboriginal arts centre model. The men’s shed provides a place for men to focus their energies on self-led healing through arts practice and collectivity, away from potentially damaging self-medication like grog. As Djon Mundine mentioned in his speech on the opening night of Shock and Ore at Coconut Studios, the sale of grog in Tennant Creek has a long, traumatising, contested history, swinging between the desire for self-determination in the Aboriginal community and the legal endowment of the capitalist, settler-colonial right for shop-owners to profit from its destructive force. Many of the members of the Brio have spent time in gaol, rendering the men’s shed a supportive structure partly aimed at keeping the men out of the carceral system.

Various discarded petrochemical vessels are the substrate for Clifford Thompson’s works. Forty-four-gallon drums are stacked to form towering pillars in his Product of India (2022). The pillars are decorated with vertical blue and white stripes, recalling the practice of the ceremonial painting of hollow logs in other parts of the Territory. Rather than painting on tree trunks, the material here is a vessel used to transport petrochemical substances from India to Tennant Creek. Product of India can be understood as a muted and cogent critique of the marriage between the mining industry and the production and circulation of Indigenous art (for example, BHP’s partnership with Tarnanthi). Yet, like other work by the Brio, it’s also, importantly, a bone-deep engagement with Indigenous aesthetics and materiality.

Adjacent to Thompson’s petrochemical memorial poles are works by Fabian Brown and Rupert Betheras. Hanging on a wall is Angels don’t smoke (2022), a large, retro Holden tonneau tray-cover is adorned with a black angel with a cigarette and a puff of smoke emerging from its mouth, painted by Brown and Betheras. Electric white hair runs down the angel’s back, morphing into skyward wings. Words float above the angel’s smoke cloud: “IF YOU’RE AN ANGEL STOP SMOKING!” wryly recalling aphorisms of Deadly Choices anti-smoking campaigns. The delinquent angel’s pose and mane mimic Holden’s lion insignia, as if the car’s badge has melted and been reincarnated in Brown and Betheras’ parallel pictorial universe.

As with Product of India, there is a seeming irreverence in some of the collaborative paintings by Brown and Betheras, towards both Indigenous and Christian cosmologies. In congregation with the smoking angel are fantastical figures like the dragon and druid in the diptych Druid dragon (2020). Here the fiery dragon and tea-sipping druid are rendered in a gruffly resonate and varied coat of yellow enamel, which applied directly to the wooden substrate has curled up, giving the surface the appearance of wrinkled skin.

The Brio dip between, evade and deploy Indigenous, Christian and pre-European signification, where the typical expectation of Indigenous painting from remote regions is the portrayal of topographical and ancestral stories. This isn’t to say the Brio don’t engage in such stories; rather they do so by enacting a kind of radical acceptance of kin, in the vein that Liboiron outlines, refusing conformity to cultural essentialism. Looking at the fucked-up past and present of extractive industries that scar community and Country, the Brio respond to their immediate environment with directness and intensity, and in so doing perform a telescopic retrieval of ancestral significance.

Lauren Burrow is an artist from Darwin, living and working on Wurundjeri Country and Boon Wurrung Country.

Tristen Harwood is an Indigenous writer, living and working on Wurundjeri Country and Boon Wurrung Country.

Shock & Ore is curated by Erica Izett.